December 10, 2012 The KKK and the Birth of the Superhero

I was maybe ten when someone threw a burning cross in a front yard down the street from our house. I didn’t know the family who lived there, just the fact that they were black. My dad doubted it was the Klan, just some local Neanderthals. Maybe the same ones who egged our house and wrote “Niger Lovers” on our garage years before. (Presumably real Klan members would spell the racial slur correctly).

I was too busy reading Marvel Comics to think much more about it, but I mention the event as a kind of apology for one of the more unpleasant discoveries I’ve made while following the superhero back to its origins.

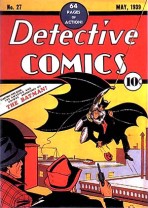

When searching for superhero ground zero, many scholars point to Baroness Orczy’s 1905 Scarlet Pimpernel largely because of Johnston McCulley’s imitative Zorro in 1919, which in turn influenced the 1939 Batman (Bill Finger included stills from the Douglass Fairbanks film when he handed his scripts to Bob Kane to draw).

But the Scarlet Pimpernel lacks one of the superhero’s most defining characteristics. He has no costume, no repeating physical representation. He is only a name and a series of ordinary disguises. (He’s also remarkably non-violent, preferring to deter an enemy with a snuff box of pepper than a blow to the jaw.)

Another historical novel published in 1905 offers a more convincing (though disturbing) predecessor to the modern superhero. Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman is a fancifully offensive portrayal of the KKK as a heroic band of Southern patriots battling the corruption of Northern tyranny. They are also the first 20th century dual identity costumed heroes in American literature.

Like superheroes, Dixon’s clansmen keep their alter egos a secret and hide their costumes with them (“easily folded within a blanket and kept under the saddle in a crowd without discovery”). They change “in the woods,” the nineteenth-century equivalent of Clark Kent’s phone booth (“It required less than two minutes to remove the saddles, place the disguises, and remount”). Their powers, while a product of their numbers and organization, border on the supernatural (their “ghostlike shadowy columns” rode “through the ten townships of the country and successfully disarmed every negro before day without the loss of a life”).

Dixon’s novel was so popular it became the source material for D. W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation, which in turn proved so successful, it inspired the Klan to reform across the U.S. (Their defining emblem, the burning cross, was invented by Dixon. The Reconstruction-era Klan never used it.)

The new KKK numbered in the millions and was praised as a much needed crime-fitting force that succeeded were traditional law enforcement failed. Historian Richard K. Tucker sums it up well:

“Mainline Protestant ministers often praised the Klan from their pulpits. Reformers welcomed it to vice-ridden communities to ‘clean up’ things. Prohibitionists and the Anti-Saloon League supported it as a force against the Demon Rum. Most of all, millions saw it as a protection against the Pope of Rome, who, they believed, was threatening to ‘take over America.'”

Vice-ridden communities, plots against America, only one thing can save us–any of this sound familiar?

There is an upside though. By the early 30s, the Klan were losing public approval. Though masked heroes sold millions of pulp magazines during the Depression, real life vigilantes were prosecuted as criminals. As a result, Superman began his career as a paradoxical vigilante-fighting vigilante, breaking up a lynch mob in the opening pages of Superman No. 1 in 1939

Superman and the legion of imitations who followed him take some of their most defining characteristics from the Klan (costumes, masked identities, codenames, emblems), while reversing the Klan’s political aims. As a result the superhero is a contradiction. A violent, anti-democratic vigilante fighting for law and order.

Dixon’s literary vision lived on in two incarnations from my childhood. Those Neanderthals roaming the suburbs of Pittsburgh in the early 70s. And the comic books I read then and am only now beginning fully to understand.

[If you’re interested in a fuller treatment of this argument, see “The Ku Klux Klan and the birth of the Superhero” in Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. The article goes online for subscribers this week and will be available in print later this year.]

Tags: Batman, D. W. Griffth, Ku Klux Klan, Niger lovers, Scarlet Pimpernel, Superman No. 1, The Birth of a Nation, The Clansman, Thomas Dixon, Zorro

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

Permalink # Why Do We Love Batman But Hate Superman? | Superman – The Man of Steel said

[…] American heartland, exemplifying American values. Siegel and Shuster, comics scholar Chris Gavaler has argued, may have been partially inspired by KKK pulp fiction like The Clansman, from which superheroes […]

Permalink # Why Do We Love Batman But Hate Superman? - The New Republic - All Inclusive said

[…] American heartland, exemplifying American values. Siegel and Shuster, comics scholar Chris Gavaler has argued , may have been partially inspired by KKK pulp fiction like The Clansman, from which superheroes […]