October 16, 2023 My Favorite 1800 Ethiopian Christian Comic

While our smallville college took a 4-day weekend (AKA, “reading days”), Lesley and I escaped for an overnight in the comparative metropolis of Richmond. The trip included a meandering afternoon in the Virginia Museum of Fine Art, where (it should surprise no one) I viewed many paintings through a comics lens.

The most obvious first:

Ellsworth Kelly’s 1966 Four Panels: Green Black Red Blue is as old as I am. It’s a reminder that panels are physical objects, and that what we call “panels” in comics studies are only drawings of panels. Are the areas of gallery wall visible between the panels “gutters”? I’m not sure. But negative spaces are conceptually part of the artwork, and so Four Panels requires a wall of some kind, and apparently a white one is preferable. I also like the Kelly quote the VMFA curators included: “I am less interested in marks on the panels than in the presence of the panels themselves.” Sounds like comics theory to me.

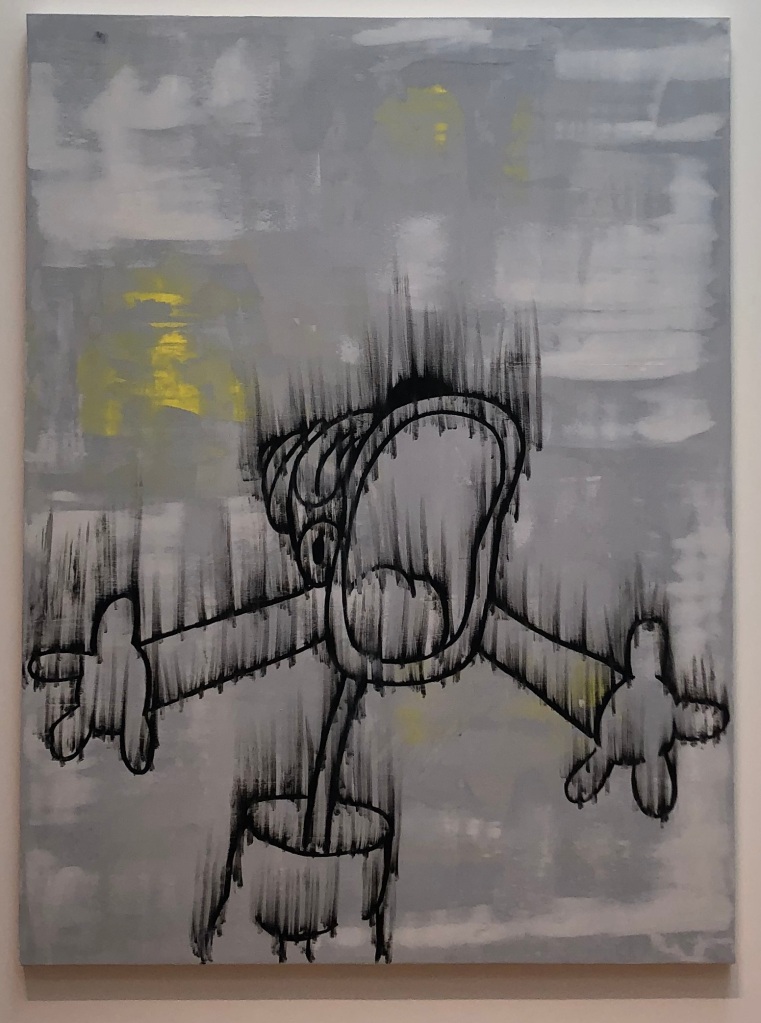

Next up, Gary Simmons’ 2020 Screaming into the Ether:

The VMFA curators say it better than I can:

I’ll just add how synchronistic it feels to be introduced to Simmons the same week I sent a final draft of my “Reading Race in the Comics Medium” to be published by the German comics journal Closure. The essay doesn’t include Basko or other Looney Toons, but it does offer a close analysis of the blackface minstrelsy drawing norms that Jack Kirby inherited from Will Eisner’s “Ebony White” and Charles Wojtkoski’s “Whitewash Jones.”

I’ve also been theorizing page whiteness in relation to racial color as part of the same book project, and so I paused a very long time over Franz Kline’s 1955 Untitled and the quotation the curators selected to hang beside it on a white wall: “People sometimes think I take a white canvas and paint a black sign on it, but this is not true. I paint the white as well as the black, and the white is just as important.”

The statement suggests so much about the apparent invisibility of racial whiteness when treated as an unchallenged norm, but I’ll dive into that another time.

Because right now I want to talk about my favorite comic in the VMFA:

It’s titled The Descent from the Cross, Burial, and Ressurection. The artist sadly is “unrecorded,” but the tempera-on-cloth painting is from Ethiopia, where the “images formed part of a larger cycle of biblical scenes lining interior walls of a church sanctuary.” The VMFA dates it “ca. 1800.”

While Simmons’ painting draws from cartooning traditions, and Kelly’s painting divides into multiple panels, I wouldn’t call either a “comic.” And not just because I avoid the word generally. I also wouldn’t say either is a “work in the comics medium” or a “work in the comics form.” But the Ethiopian sequence is definitely in the comics form (note the curators refer to the work as multiple “images,” not as a single subdivided one), and its viewing path even prefigures 20th-century comics medium norms:

Any manga fan is familiar with right-to-left viewing, though here the horizontal direction is initially secondary to the vertical top-to-bottom viewing. In comics terms, the sequence follows an N-path. More interestingly, the first direction-establishing panel (in the comics sense of the word, since the work is a single piece of cloth) is actually two images. Or rather the comics panel includes two distinct diegetic moments occurring within the same diegetic space enclosed within a single drawn frame. In The Comics Form, I call that an “embedded juxtapositional inference” (“the perception and division of a discursively continuous image into multiple diegetic images”). The two recurrent images of Christ create that perception (“recurrence” is “a quality of multiple images that represent the same subject”), and the third recurrent image in the top middle panel creates a “hinge” between panels (“juxtapositional inferencing that produces directed paths”). It’s because The Descent from the Cross, Burial, and Ressurection isn’t in the comics medium that formal analysis is necessary. Church-goers in 1800 Ethiopia presumably did not have experience with comics conventions and so would have needed to discover the painting’s viewing path themselves.

According to the curators, the images follow this sequence:

Actually they refer to the “scene of hell” ambiguously, as though it existed in some way outside of the sequence — which diegetically it does: the demonic face may be understood as an outside observer of the events depicted in the other panels. The sleeping guards are not fully sequenced either, since the events of panels 3 and 4 could occur simultaneously. That produces a variable viewing order:

That would also mean that the first two-image column is unified by spatial inferencing, and the second and third two-image columns are unified by temporal inferencing.

Whatever the viewing order, to analyze the painted cloth as sequenced images is to analyze it as a comic. Which is a problem if you are committed to the view that “comics” is an anachronistically forbidden term when applied to art created before 1890.

That’s also why I think the comics form and its various qualities might be useful concepts to apply both in and outside comics studies. If I write a second edition, I’ll need to include The Descent from the Cross, Burial, and Ressurection.

Tags: and Ressurection", Burial, Ellsworth Kelly, Four Panels: Green Black Red Blue, Franz Kline, Gary Simmon, Screaming into the Ether, The comics form, The Descent from the Cross, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

Leave a comment