September 26, 2016 Top 8 Superhero Comics, 1971-2000

It’s hard leaving out some of my personal favorites (no Sienkiewicz!), especially from my own childhood and college years, but these ongoing lists are for my book “Superhero Comics,” and my editor wants the genre’s “Key Works.” Which sometimes overlaps with “stuff Chris loves” and sometimes doesn’t. I’m also keeping the focus on the authors, and that means defining a “work” by writers and artists (usually penciller). Also, to prevent someone like Alan Moore from hogging half the slots, I’m trying to impose a one-work-per-author rule. The Comics Code was revised in 1971, the first revision since it was created in 1954, and then revised again in 1989, so those are my historical markers.

Second Code Era, 1971-1988:

Claremont & Byrne’s The Uncanny X-Men (1977-81).

Chris Claremont has the longest run on any comics title. After Len Wein and Dave Cockrum’s one-issue reinvention of the series, which had been reprinting 1960s issues since #67 (December 1970), Claremont wrote The Uncanny X-Men from #94 (August 1975) to #279 (August 1991), as well as numerous spin-off titles including New Mutants, Wolverine, and X-Men #1 (October 1991), the highest selling comic book of all-time. John Byrne pencilled and often co-wrote #108 (December 1977) – #143 (March 1981), before moving on as writer-artist of a wide range of Marvel and DC titles including Alpha Flight (1983) and the Superman reboot mini-series The Man of Steel (1986). Byrne further developed the Adams-influenced visual style that would continue to define superhero comics for the next decade, and Claremont’s long-term approach to multi-issue plotting and characterization became increasingly standard. Claremont and Byrne’s joint run includes the X-Men’s most acclaimed narrative arc, The Dark Phoenix Saga, #129-138, ending with the death and funeral of Jean Gray—events Bryne would help to retcon out of existence during his five-year run of The Fantastic Four in 1986. Instead of Byrne, Claremont initially partnered with Neal Adams for God Loves, Man Kills (1982), one of the first graphic novels published in the Marvel Graphic Novel format, but because Adams refused a standard work-for-hire contract, Marvel replaced him with Brent Anderson. Byrne returned to Marvel in the late 80s to work on several titles including West Coast Avengers and Sensational She-Hulk, after which he wrote creator-owned titles for Dark Horse Comics.

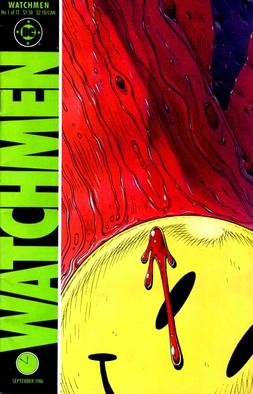

Moore & Gibbons’ Watchmen (1986-87).

The most acclaimed superhero comic of all-time, the twelve-issue Watchmen, along with Frank Miller’s four-issue The Dark Knight Returns (1986), marks a major turning point in the genre, with a leap in psychological realism and a rejection of the Code-mandated triumph of absolute good over absolute evil. Moore initially plotted the series with characters DC had recently acquired from the defunct Charlton Comics. When editors objected, he and Dave Gibbons nominally redesigned the cast, creating morally flawed counterparts that interrogate the decades-old norms of the superhero character type. Because the series stood apart from the rest of the DC universe, Moore and Gibbons received unusual creative freedom, and the limited series format also enabled them to work in a closed narrative form that barred sequels, a rarity in comics at that time and a major factor in the series’ excellence. Time magazine listed Watchmen in its one hundred best English-language novels published since 1923 (Grossman 2010). Moore’s other major works include Marvelman / Miracleman (1982-89), V for Vendetta (1982-88), The Saga of the Swamp Thing (1984-87), From Hell (1989-96), and The League of Extraordinary Gentleman (1999-2003).

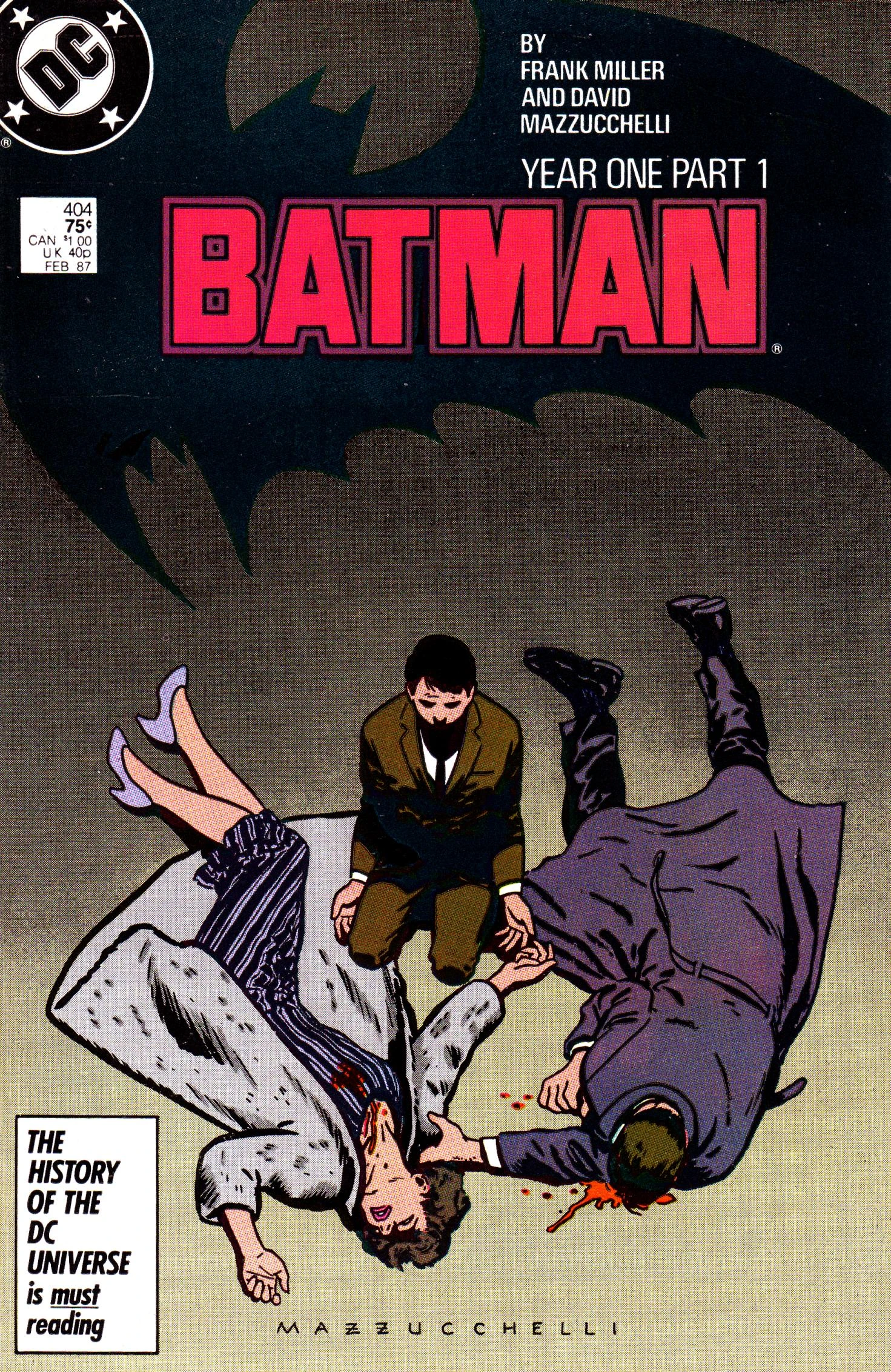

Miller & Mazzucchelli’s Batman: Year One (1987).

Following the successes of his first Daredevil run (1979-1983), Ronin (1983-84), and The Dark Knight Returns (1986), Frank Miller partnered with artist Bill Sienkiewicz for the graphic novel Daredevil: Love and War (1986) and the limited series Elektra: Assassin (1986-87) and penciller-inker David Mazzuchelli for the 1986 Born Again arc in Daredevil and DC’s history-redefining Year One arc in Batman #404 (February) – #407 (May 1987), ending Miller’s most productive period with DC and Marvel, after which he began publishing with Dark Horse. Year One, Born Again, and The Dark Knight Returns are widely regarded as Miller’s best work. Born Again, however, is marred by a literal deus ex machina ending, and though less genre-influencing than the fascist-leaning Dark Knight Returns, Year One’s time scope pushed Miller into storytelling innovations where John Byrne’s parallel The Man of Steel suffers in contrast. Unlike the sometimes cartoonish excesses of Miller’s Dark Knight Returns art, Mazzuchelli’s comparatively sparse style provided a realistic baseline rendered in short, grainy lines for the series’ much praised gritty effect. Mazzuchelli soon left superhero comics, publishing an adaptation of Paul Auster’s postmodern detective novel City of Glass in 1994 and the even more highly acclaimed Asterios Polyp in 2009.

Gaiman’s The Sandman (1988-1996).

Gaiman’s The Sandman (1988-1996).

Neil Gaiman entered comics as a fan of Swamp Thing and then as a journalist, interviewing Alan Moore and other creators for a 1986 Sunday Times Magazine article that was never published because the editor was expecting a Wertham-esque critique of the industry (Gaiman 2016: 265, 233). DC first hired him for the 1987 Black Orchid limited series with the Sienkiewicz-influenced artist Dave McKean, after which Gaiman requested Sandman, a minor and largely forgotten superhero created by Gardner Fox and Bert Christman in 1939 and briefly reinvented by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby in 1974. Working with a wide range of artists including McKean for covers, Gaiman wrote the entire series, from #1 (January 1989) to the final #75 (March 1996), creating one of DC’s most popular titles of the 90s and drawing acclaim and readership from outside traditional comics audiences. Reprint compilations sold well in trade paperback formats, expanding readership beyond direct market comic shops to general bookstores. Though the title began before DC instituted its creator-owning imprint Vertigo in 1993, Gaiman retained copyrights, and when he left the series, it and its characters were not continued. Gaiman moved from comics to a highly successful and ongoing career in literary speculative fiction.

Third Code Era, 1989-2000:

Morrison & McKean’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth (1989).

The term “graphic novel” emerged in the 70s, and Marvel published “Marvel Graphic Novel” and “Epic Graphic Novel” imprints in the 80s that featured stand-alone works rather than collected reprints of pre-existing series. “DC Graphic Novel” used the same trade paperback format, but Arkham Asylum, published the October after the summer release of Tim Burton’s Batman film, was one of the first graphic novels printed in hardback—then a norm of non-comics literary publishing. It soon became one of DC’s best-selling graphic novels. Writer Grant Morrison had joined DC a year earlier, reviving the character Animal Man in a limited and then ongoing series and then Doom Patrol in early 1989. When DC assigned Arkham to artist Dave McKean, Morrison revised his original 48-page script into a 67-page, screenplay-like format, giving McKean greater freedom for his expressionistic paintings, which expanded to 120 pages. Morrison later worked on a wide range of superhero titles, including his own creator-owned The Invisibles (1994-2000).

McFarlane’s Spawn (1992).

Because Marvel refused to share copyrights, a prominent group of creators, including Spider-Man artist Todd McFarlane and X-Men writer Chris Claremont, left the company to form Image Comics in 1992. Spawn #1 (May 1992), one of Image’s first publications, was a top-selling superhero comic of the year, drawing new attention to independent publishers in the Marvel-DC dominated market. Image joined Eclipse, which had formed in the late 70s and was publishing Alan Moore’s and briefly Neil Gaiman’s Miracleman, and Dark Horse, which had formed in 1986 and featured Paul Chadwick’s Concrete and soon Mike Mignola’s Hellboy. Image Comics, distributed entirely through the increasingly dominant direct market system, never joined the Comics Magazine Association of America and so Spawn and its other titles were never subject to the Comics Code. Though McFarlane partnered with various guest writers, including Moore and Gaiman, their contributions are largely forgotten, and Spawn is remembered primarily for its impact on the wider industry. McFarlane, along with fellow Image artists Rob Liefeld and Jim Lee, also defined the hypermuscular and hypersexualized style of the 90s. Despite its emphasis on creator rights, Image, using the work-for-hire argument Marvel used against Jack Kirby, claimed full copyright of the character Angela co-created by Gaiman and McFarlane and introduced in Spawn #9 (March 1993). Gaiman won a lawsuit against Image in 2002, after which McFarlane relinquished his rights and Gaiman sold the character to Marvel where Angela was introduced in 2013.

![]() McDuffie & Bright’s Icon (1993-97).

McDuffie & Bright’s Icon (1993-97).

Another independent publisher, Milestone Comics formed in 1993 but in a distribution partnership with DC with both company logos appearing on covers. Milestone consisted entirely of African American creators who retrained ownership and creative control of their work. Dwayne McDuffie wrote or co-wrote all four of the initial titles, including Icon, penciled M. D. Bright, who, like McDuffie, had worked on previous superhero titles for DC and Marvel. The two collaborated on all but five issues of the complete run, #1 (May 1993) to #42 (February 1997). The series features a Superman-like hero who, instead of landing in the 20th century mid-west to be raised by white farmers, lands in the Antebellum South to be raised by an enslaved plantation worker. His Robin-like sidekick, Rocket, is black teenager whose out-of-wedlock pregnancy and motherhood are central themes of the series. The series is widely praised for bringing a diversity of accurately portrayed black characters to superhero comics. Icon ended when the market collapse of the mid-90s drove Milestone out of the comics business.

Waid & Ross’ Kingdom Come (1996).

Waid & Ross’ Kingdom Come (1996).

The limited series Kingdom Come, #1 (May 1996) – #4 (August 1996), was co-written by Mark Waid and Alex Ross and painted by Ross. As an Elseworld imprint, the story features a wide range of DC superheroes, but outside of company continuity, enabling Waid and Ross to freely interpret and in some cases kill characters in a plotline involving the morally indifferent children of today’s heroes. Ross conceived the story while working with writer Kurt Busiek on the similar, four-issue Marvels (1994), and DC teamed him with Alex Waid, who had written for range of Marvel and DC titles, including Captain America and The Flash. The work is most significant for marking the highpoint of photorealism in the genre. In contrast to the comparably cartoonish standards of the period, Ross worked from live models and, instead of following the pencils-inks-colors process norm of the industry, painted in his preferred medium of opaque watercolors. While Bill Seinkiewicz and Dave McKean had achieved similar moments of painterly photorealism, Ross maintained the style across his work. Due to the labor intensiveness of the approach, he produced mainly cover art after Kingdom Come.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

Leave a comment