April 15, 2024 Blue May No Longer Be the Warmest Color

I checked my old syllabi, and Jul Maroh’s Blue is the Warmest Color is tied for my most-taught graphic narrative. Beautiful Darkness will likely move to a lone number one slot next time I teach Intro to Graphic Novels though, because my current class has convinced me to retire Blue is the Warmest Color.

First, a quick author update:

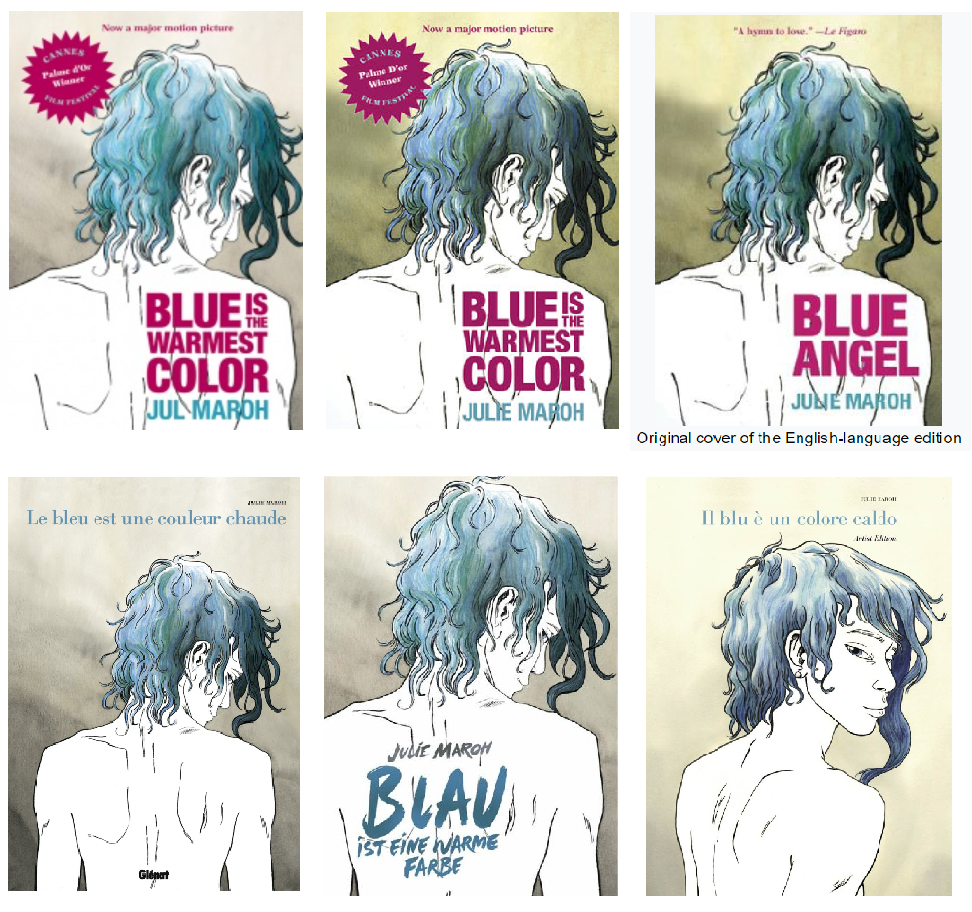

The novel was first published in 2010, and Maroh revealed that they are non-binary in (I think) 2022. Their various publishers are still catching up — most distressingly their English-language publisher, which means Maroh is still being dead-named on some of their covers.

If you’re curious, you can track the evolution of their first name from its original appearance, to its contracted abbreviation at their former blog, to its current non-abbreviated “Jul.”

The author’s gender identity doesn’t excuse the catastrophe of the 2013 film adaptation by Abdellatif Kechiche.

I show the trailer in class, while discussing Laura Mulvey’s 1975 classic essay on the male gaze.

I share Maroh’s critique too:

“It appears to me this was what was missing on the set: lesbians. I don’t know the sources of information for the director and the actresses (who are all straight, unless proven otherwise) and I was never consulted upstream. Maybe there was someone there to awkwardly imitate the possible positions with their hands, and/or to show them some porn of so-called “lesbians” (unfortunately it’s hardly ever actually for a lesbian audience). Because — except for a few passages — this is all that it brings to my mind: a brutal and surgical display, exuberant and cold, of so-called lesbian sex, which turned into porn, and me feel very ill at ease.”

I also share Maroh’s thoughts about the novel’s intended audience:

“I didn’t make a book in order to preach to the choir, nor only for lesbians. Since the beginning my wish was to catch the attention of those who:

“–had no clue

“–had the wrong picture, based on false ideas

“–hated me/us”

And that’s when class discussion moved in an unexpected direction.

The room coalesced around three central critiques.

First, the age difference between the characters begins their relationship with an imbalanced power dynamic. When they meet, Clementine is 15, and Emma is in college. They have sex for the first time when Clem is 17. Someone googled “age of consent in France” (it’s 15), but that defense felt (literally) legalistic.

I thought discussion of the second half of the novel would soften the criticism. I was wrong. Yes, they’re older (Clem is 30 by the end), but the room felt the relationship remained fundamentally co-dependent. They were described as addicts, and when Clem is without Emma, she becomes literally addicted to a (substitute) drug.

Third critique: the relationship seems much more about physical sex rather than emotional depth. Given the “explicit sex” content warning I put on my syllabus, it’s hard to argue against that.

I suggested that all of the critiques may have more to do with rejecting romance genre tropes (love at first sight, I can’t live without you, etc.), but that only reinforces the fact that Maroh employs them. I also pointed out that a lot has changed since 2010. But, again, that only reinforces the fact that it’s 2024.

So now I have to ask myself: Why have I taught the novel so many times?

It may sound superficial, but I love its formal approach to layout. Not just in the abstract, but how Maroh employs layout effects to express her characters’ emotional lives, complexly merging form and content.

Also, it’s a lesbian romance.

The combination seemed ideal to me. Still does. Though now, yes, I also fully acknowledge that imbalanced power dynamics, emotional co-dependence, and an overemphasis on sex are all traits of an unhealthy relationship. They always were, but I previously ignored them as less significant genre qualities, content to focus instead on how the novel flouted the primary romance trope of heterosexuality.

After drafting this post, I reported the class discussion to one of my English department colleagues and visiting novelist Sarah Thankam Matthews (whose All This Could Be Different I’m dying to read as soon as I clear my digital desk of final papers and exams, but whose short story “Rubberdust” you should read right now). They were both describing similar class discussions, alarmed by what they called the legalistic reaction of students objecting to the sexual behavior of fictional characters on ethical grounds. I would need more data to speculate on how widespread the trend is or isn’t, but it sounded like they’d both been eavesdropping on my comics class.

But one more unexpected turn: on the last day of class I asked the room which novels they recommend I keep or replace, and several students (including two who were among the most adamant in their critiques) lobbied to keep Blue is the Warmest Color on my future syllabi. Yes, the relationship is problematic, but they found it engaging despite — and possibly because of — those problems. In short, they really enjoyed analyzing the novel so thoroughly, something its flaws encouraged.

Meanwhile, their top two must-keeps were happily the same as mine:

Tags: Blue is the Warmest Color, Jul Maroh, sarah Thankam matthews

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

Leave a comment