Monthly Archives: February 2014

24/02/14 Virtual Justice

Emily Bazelon likes superheroes. Her New York Times Magazine article “The Online Avengers” chronicles the adventures of Anonymous hackers who use their powers to combat cyber-bullying. Bazelon says Anons tend to think in “polarized terms,” viewing their cases as “parables with an innocent victim, evil perpetrators and ineffectual (or corrupt) law enforcement,” all staples of the superhero genre. But Bazelon enjoys some of those polarized terms too, describing how her aliased Avengers “team up” or “join forces” to expose “wrongdoers.” She draw one activist in origin story rhetoric: “He vowed that day he would do something about Rehtaeh Parsons’s death.”In Bazelon’s defense, the rhetorical infection seems to originate with the Anons she interviews. “We wanted to strike fear into their hearts,” declares one Batman wannabe. They even wear Guy Fawkes masks from Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta.

But it’s the wrong metaphor. These aren’t caped crusaders patrolling the mean streets of Gotham. The streets are Facebook and Tumblr. The superpowers are laptop-based. Many of the crimes—posting a video on YouTube or a message on Twitter—take place in the no man’s land of the world wide web. The bad guys can live anywhere on earth, but they elude justice by exploiting a virtual frontier.

What we have here is a Western.

Owen Wister largely invented the genre when he published The Virginian in 1902. His bad guys disappear into the mountain sanctuaries of Wyoming: “He that took another man’s possessions, or he that took another man’s life, could always run here if the law or popular justice were too hot at his heels. Steep ranges and forests walled him in from the world on all four sides, almost without a break; and every entrance lay through intricate solitudes.”

When journalist Amanda Hess dialed 911 after receiving death and rape threats via Twitter, the Palm Spring cop who arrived at her door dismissed them because the “guy could be sitting in a basement in Nebraska for all we know.” The bad guy was safe in the intricate solitudes of his IP address. Hess documents her experience, and dozens like it, in her recent Pacific Standard essay “Why Women Aren’t Welcome on the Internet.” When Caroline Criado-Perez received similar threats after petitioning the British government to include women on its currency, she retweeted them until the international attention forced police to respond. They said it was Twitter’s problem. Twitter said threatened users should contact local authorities.

Wister’s Wyoming faces the same failure of law enforcement. Because “the law has been letting our cattle-thieves go,” a former judge declares: “We are in a very bad way, and we are trying to make that way a little better until civilization can reach us. At present we lie beyond its pale. The courts . . . into whose hands we have put the law, are not dealing the law. They are withered hands, or rather they are imitation hands made for show, with no life in them, no grip. They cannot hold a cattle-thief.”

But Bazelon’s Avengers are skilled at tracking cattle-thieves’ user IDs through walled websites and forests of social media. When four teens in Texas tweeted gang rape threats at a twelve-year-old in New Zealand, the team of Anons unmasked their Twitter handles and forwarded evidence to the boys’ highs school administrators. The Virginian’s punches are “sledge-hammer blows of justice.”OpAntiBully settles for screenshots.

When Rehtaeh Parsons’s mother received evidence of her daughter’s rape, she turned it over to OpJustice4Rehtaeh, an Anonymous group she originally distrusted as nameless vigilantes. But, she told Bazelon, “if pressure from this group is what it takes, let them do what they do.”

Wister’s judge reasons similarly: “And so when your ordinary citizen sees this, and sees that he has placed justice in a dead hand, he must take justice back into his own hands where it was once at the beginning of all things. Call this primitive, if you will. But so far from being a DEFIANCE of the law, it is an ASSERTION of it—the fundamental assertion of self governing men, upon whom our whole social fabric is based.”

Local authorities tend to disagree. When badgered into reopening a rape case by OpMaryville and Justice4Daisy, the sheriff of Maryville, Missouri complained: “They all need to get jobs and quit living with their parents.” Parsons’s alleged rapists—or at least the two who posted the YouTube video of the crime—are now facing child pornography charges, though a police spokesman warned that OpJustice4Rehtaeh could come under investigation too.

Meanwhile, Cattle-thieves have their own advocates. Hess reports that the Electronic Frontier Foundation—a free speech and privacy rights group—lobbied against the Violence Against Women Act because an amendment updating phone harassment to include any electronic communication. When Hess started receiving threatening voicemails on her own cell phone and police still refused to make a report, she took the law out of their withered hands. She tracked the guy’s IP address, filed a civil protection order, hired a private investigator to serve court papers, and got a judge to approve a restraining order that included everything from Twitter to hot air balloon messaging.

Which is to say Hess is no vigilante.

When the Virginian catches horse-thieves, he lynches them. That means Wister and his judge have to spend a lot of their frontier rhetoric differentiating this private but supposedly law-and-orderly form of capital punishment from the “semi-barbarous” lynching and burning of “Southern negroes in public.” Apparently the swift hanging of “our criminals” puts no “hideous disgrace upon the United State.”The judge doesn’t quibble over the definition of a “criminal” though, since the term denotes someone who has been legally tried and convicted, a luxury Wister’s frontiersmen forgo.

The Virginian ends his adventures when his once-skeptical love interest accepts his system of retribution and marries him. By the end of Bazelon’s article, her lead Avenger has lost his girlfriend of nine years—she complained he never turned off his laptop at night. Hess mentions a boyfriend but would rather write about the “Frontier of Female Sexuality” and “the gun-toting, boob-grabbing douchebags who are subsidizing your online porn habit.” She’d also like to see internet harassment prosecuted as a Civil Rights issue, a wonderfully civilized aspiration far beyond the pale of the current U.S. legal system.

In the meantime we’re left with faceless superhero wannabes trying to make our virtual frontier better until civilization can reach us.

Tags: Amanda Hess, Anonymous, Emily Bazelon, Owen Wister, The Virginian

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

17/02/14 Avengers Assemble! The American Novel Since 1950

As a kid reading comics, I loved when superhero teams scrambled their rosters. For The Avengers No. 137, “We Do Seek Out New Avengers!,” Vision and the Scarlet Witch left on their honeymoon, Yellowjacket and Wasp rejoined, and Moondragon replaced the recently deceased Swordsman, leaving Hawkeye’s spot (he went off in a time machine to find the Black Knight) to be filled via an open call at Shea Stadium, where only the Beast showed up. Sounds easy, but when the Defenders televised a similar recruiting call three years later, the team was inundated with 23 would-be members, from canonical crushers Captain Marvel and Iron Man (cover appearance only) to inspired backpagers White Tiger and Prowler.

The Defenders No. 62 cover features team leader Nighthawk holding his apparently throbbing head and roaring at the impressionistically pint-sized heroes buzzing around him. Which is how I feel as I juggle the roster for a would-be course on the recent American novel. Even my open call “I Do Seek Out American Novelists!” attracts trouble, since that Canadian crusher Margaret Atwood showed up in the Shea Stadium of my brain (so does that mean I have to add “North” to the course title?). I already sent her Nobel-winning countrywoman Alice Munro home on a technicality (“Novel” not simply “Fiction”), which still leaves over twenty superpowered authors buzzing across my cover.

Writer Steve Englehart and editor Marv Wolfman weighed a dozen factors when revising the Avengers in 1975. It must be hard tossing out fan favorites like Wanda and Vision, but see how they replaced them with another married couple? And notice how they improved gender distribution by swapping in Moondragon? (Though, okay, the female count plummeted back to one when Wasp gets hospitalized in her return issue). Of course you still want some of the old standards, Thor and Iron Man, while leaving room for an unexpected choice like the newly blue-furred Beast. And what happens when you put all these costumes in the same room? How do they get along?

Syllabus-assembling makes the same demands: are these powerful books, a balanced range, what story do they tell when they stand shoulder-to-shoulder? By balanced, I mean are half by women? Are half not by white authors? It’s not political correctness but good storytelling. If a course representing the last sixty or so years of the American novel consists mostly of Caucasian men, the story is: white guys write the best stuff. That’s a stupid story, so I know four of my roughly eight slots are going to be filled by women, and four by non-WASPs. Though that doesn’t reduce the swarm of authors in Shea Stadium much.

The Englehart-Wolfman Avengers range from the team’s oldest character (Henry Pym was buzzing around in 1962) to the two-year-old Moondragon (plucked from the 1973 pages of Daredevil). When I taught a 21st century American lit course, I had about the same age range and so felt free to juggle the reading order by convenience and whim. But a span of sixtysome years requires a more disciplined time machine. Start in the 50s and bound forward decade by decade. That draws attention to gaps though, so suddenly distribution matters too. That’s one of many good reasons that Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony made my first cut, as a rep of my underpopulated 70s favorites (I prefer that decade’s short stories). It also means my overpopulated 80s is a problem, so DeLillo’s White Noise could be in trouble.

And what about genre types? In addition to two insect-sized humans, the 1975 Avengers include a mutant, an alien-trained telepath, a cyborg, and a god. So I should probably hit the key literary schools too. Pynchon is an easy pick for Metafiction, though Nabokov’s Pale Fire is even more fun. New Journalism’s “nonfiction novel” list is harder to prune: Capote, Mailer, Thompson, Didion, and of course my college’s beloved alum Wolfe. But if experimental memoirs are fair game, then I want Kingston’s Woman Warrior on my team (okay, maybe I do like the 70s). So maybe it’s better to swat away all things nonfiction?

I called my 21st century fiction course Thrilling Tales and focused on the pleasant collision of traditional literary novels with the formerly lowbrow genres of scifi, fantasy and mystery. I could make the second half of the 20th century an Old Testament to that thesis. Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is an alternate future, and Morrison’s Beloved a ghost story. Chabon won his Pulitzer for transforming superheroes into literary subject matter, and what’s The Crying of Lot 49 but a riff on thriller conventions? Egan’s genre-splicing A Visit from the Goon Squad could cap it all, and, for a truly blue-furred freak, I could shoehorn in Watchmen (I know, Alan Moore is British, but his and Dave Gibbons’s collaboration was very American, which, by the way, made Time’s ALL-TIME 100 Novels, thank you, Lev Grossman).

If you want to push the genre angle even further, swap out Flannery O’Connor for Patricia Highsmith. Or revise the subtitle to “Since World War 2” and open with Wright’s Native Son. Trade Pale Fire for Lolita and suddenly the course opens with a legion of supervillains: Bigger Thomas, Mr. Ripley, Humbert Humbert. Maybe I need to read Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho next? Baker’s The Fermata is a bound too far, though White Noise and its “Hitler Studies” is back in the running. I was thinking about Jones’ The Known World, but I just finished Whitehead’s Zone One, and all those zombies pair so well with the horrors of Beloved and the shadowy PTSD of Ceremony. Maybe the name of this course is American Monsters?

I was nine when I started reading The Avengers. My students are about nineteen, but they have something in common with my former Bronze Age self. Englehart and Wolfman mixed and matched their roster, knowing theirs was just the latest incarnation of a team other writers would continue to juggle for decades. But No. 137 was the first Avengers comic I ever saw. This wasn’t one version of an evolving team. This was THE Avengers. And for the students on my would-be class roster, this is the only American Novel Since 1950 course they will ever take.

And at the moment it looks something like this:

1955 Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley

1966 Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49

1977 Leslie Marmon Silko, Ceremony

1985 Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

1987 Toni Morrison, Beloved

1986 Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons, Watchmen

1999 Michael Chabon, The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay

2010 Jennifer Egan, A Visit from the Goon Squad

2011 Colson Whitehead, Zone One

Tags: contemporary american novels, Marv Wolfman, Steve Englehart, syllabus, The Avengers 137, The Defenders 62

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

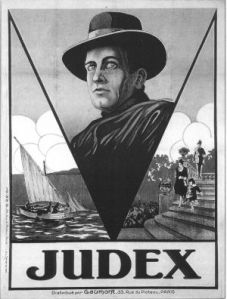

10/02/14 Judex Redux

Is anyone else tired of superhero movies?

According New York Times reviewer A. O. Scott, superheroes peaked with The Dark Knight in 2008. Since then, “the genre, though it is still in a period of commercial ascendancy, has also entered a phase of imaginative decadence.” Scott said that back in 2012, before the release of Amazing Spider-Man, Iron Man 3, The Wolverine, Man of Steel, Kick-Ass 2, Dark Knight Rises, and Thor: The Dark World —much less the still future releases of X-Men: Days of Future Past, Amazing Spider-Man 2, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Guardians of the Galaxy, The Avengers: Age of Ultron, Fantastic Four, and Batman vs. Superman.

Which is to say, he’s got a real point. All those masks and capes and inevitable act three slugfests—could we maybe call a moratorium while the screenwriters guild brainstorms new action tropes? I’m probably too optimistic that Edgar Wright’s 2015 Ant-Man will provide a much needed counterpunch to all the BAM! and POW!—the same way his 2004 Shaun of the Dead enlivened the weary corpse of the zombie movie (another genre still in decadent ascendance).

But instead of looking forward, maybe we should be looking backwards. If, like me, you crave a beer chaser for all those syrupy shots of Hollywood superheroism, tell your online bartender to stream some mid-twentieth century French avant-garde instead.

Georges Franju’s 1963 Judex has to be the least superheroic superhero movie ever made. Well into its third act, the title character (think Batman with a hat instead of pointy ears) bursts through a window to assail his enemies—only to allow one to step around him, pluck a conveniently placed brick from the floor, and sock him unconscious from behind. It’s not even a fight sequence. Everyone but the brick basher moves in a languid shuffle. The scene is one of many reasons critics label the film “dream-like,” “surreal,”“anti-logical,” “drowsy”—terms opposed to the adrenaline-thumping norms of the genre.

The original 1916 Judex, a silent serial by fellow French director Louis Feuillade, largely invented movie superheroes. The black cloaked “Judge” swears to avenge his dead father, leading to dozens of similarly cloaked avengers swooping in and out of the 20s and 30s. Judex had barely exited American theaters before film star Douglass Fairbanks was skimming issues of All-Story for his own pulp hero to adapt. A year later, the Judex-inspired Zorro was an international icon.

But Georges Franju was no Judex fan. He preferred Feuillade’s Fantomas, one of the most influential serials in screen and pulp history, and the reason Feuillade dreamed up his crime-fighter in the first place. Fantomas was a supervillain, as was Irma Vep in Feuillade’s equally popular Les Vampires, and French critics had grown weary of glorified crime. Fifty years later, Franju was still glorifying it, making one of France’s first horror films, Eyes Without a Face.

Feuillade’s grandson, Jacques Champreux, was a Franju fan—though he really should have checked the director’s other references before asking him to shoot a remake of the superhero ur-film. When the French government commissioned a documentary celebrating industrial modernization, Franju had focused on the filth spewing from French factories. When the slow-to-learn government commissioned a tribute to their War Museum, Franju used it as an opportunity to denounce militarism. Little wonder his Judex is a testament against the glorification of superheroism.

But Champreux bares some of the unintended credit too. Franju admitted to not having “the story writing gift,” but few of Feuillade’s gifts passed to Champreux either. Much of the remake’s surrealism is a result of inexplicable scripting. Champreux and fellow adapter Francis Lacassin boiled down the original five-hour serial to under a hundred minutes. While the streamlining is initially effective (opening with the corrupt banker reading Judex’s threatening letter is great), it soon creates much of that surreal illogic critics so praise:

Why is the detective so incompetent? (Because this is his first job after inheriting the detective agency.)

Why is the banker suddenly in love with his granddaughter’s governess? (Feuillade’s opening scene establishes her plot to seduce him and steal his money.)

Why set up the daughter’s engagement if her fiancé exits after one scene? (Because he originally returned as a villain in league with the governess.)

How does the detective’s never-before-mentioned girlfriend happen to find him just as she’s needed to aid Judex? (Feuillade introduced her well before, and the two were already walking together when Judex allows himself to be captured.)

How is Judex able to pose as the banker’s most trusted employee? (He took a job as a bank clerk years earlier and worked his way into the top position.)

Why is Judex even doing any of this? (His father committed suicide after the banker destroyed the family fortune and his mother made him vow to avenge his death.)

Some of Franju’s most pleasantly peculiar moments— the travelling circus that wanders past the bad guys’ hideout, the dog that appears from nowhere and sets his paw protectively on the fallen damsel’s body—are orphans from Feuillade’s plundered subplots. The remake is a highlight reel. Though, to be fair, not all of the surrealism is the result of the glitchy script.

By moving Judex’s death threat to midnight and shooting the engagement banquet as a masked ball, Franju offers the best Poe adaptation I’ve ever seen—even if all the bird costumes make it more of a Masque of the Avian Flu. And the Franju’s one fight scene isn’t derived from Feuillade at all. Originally the detective’s girlfriend attempts to save the governess who drowns while trying to escape, but Franju costumes the two women in opposite, if equally skintight attire—a proto-Catwoman vs. a white leotarded acrobat—before sending them to the roof to leg wrestle.

Instead of washing ashore in the epilogue, the governess falls to her death in a bed of flowers. Meanwhile, what’s Judex up to? Not only is the nominal hero not present for the vanquishing of the villainess, but by the end of the film he’s devolved into Douglass Fairbanks’ Don Diego, Zorro’s mild-mannered alter ego. While Franju was imitating the style of early cinema (yes, his version opens with a classic iris-out, a fun gimmick even though Feuillade avoided it in his own Judex), he also grafted Fairbanks’ goofy handkerchief magic into Judex’s less-than-superheroic repertoire. The tricks were cute in The Mark of Zorro, but once again inexplicable in the contemporary context.

And I mean that as praise. A Judex redux is exactly what the genre needs right now. I would love to watch Emma Stone toss the Lizard from a skyscraper while Spider-Man practices his web sculpting—or Natalie Portman shove a Dark Elf through a magic portal while Thor perfects a hammer juggling trick. Superhero films feature plenty of glitchy illogic, but it’s time for drowsy surrealism too. Why hasn’t Marvel or DC handed any directing reins to David Lynch yet? Or David Cronenberg? Terry Gilliam dodged The Watchmen back in the late 80s—but surely his version would have been more memorable than Zack Snyder’s. Isn’t there someone out there who can prove A. O. Scott wrong?

Tags: A. O. Scott, Francis Lacassin, Georges Franju, Jacques Champreux, Judex, Louis Feuillade

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

03/02/14 Watching the Detectives

Benedict Cumberbatch can’t throw a punch. At least not when he’s playing Sherlock Holmes. Khan in Star Trek into Darkness throws plenty of punches, but he’s a eugenically bred superman. Dr. Watson reports in A Study in Scarlet, Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel, that the “excessively lean” detective is “an expert singlestick player, boxer, and swordsman,” but we have to take his word on it.

I wouldn’t know what a “singlestick” is if not for Jonny Lee Miller’s portrayal of Holmes in the aggressively updated CBS series Elementary. A singlestick, it turns out, is a stick you smack your opponent on the top of the head with. That’s what the BBC wanted to do to CBS when they heard the Americanized Holmes was premiering in 2012, because CBS had been in talks about producing a version of the BBC’s already aggressively updated Sherlock. But then the BBC would have to accept a head smack from Warner Bros. since Sherlock premiered a year after the 2009 Sherlock Holmes hit theaters.

Sherlock is the bastard brainchild of two Dr. Who writers; Elementary midwife Robert Doherty cut his teeth on Star Trek: Voyager; and the Robert Downey Jr.’s Sherlock Holmes started life as a comic book that producer Lionel Wigman penned instead of the usual spec script. When director Guy Ritchie got his hands on it, he was thinking Batman Begins. The Marvel formula was succeeding at box offices by then too, so Holmes’ superpowered intellect would have to be “as much of a curse as it was a blessing.”

A young Holmes should have nixed the forty-something Mr. Downey, but who can say no to Iron Man? Especially when Ritchie planned to restore all of Doyle’s “intense action sequences” other adaptations left out. You know, like when Holmes sneaks aboard the bad guys’ boat in “The Solution of a Remarkable Case”:

“With a lightning‑like movement he seized the hand which held the knife. Then, exerting all of his great strength, he bent the captain’s wrist quickly backward. There was a snap like the breaking of a pipe‑stem, and a yell of pain from the captain. Nick’s left arm shot out and his fist landed with terrific force squarely on the fellow’s nose.”

Oh no, wait. That’s not Sherlock. That’s Nick Carter. I’ve been getting them confused lately, and I’m not the only one. Carter premiered as a 13-episode serial in New York Weekly in 1886, the year before A Study in Scarlet premiered in England’s Beeton’s Christmas Annual. Carter was created by John R. Coryell and Ormond G. Smith, but Street & Smith (future publisher of the Shadow and Doc Savage) hired Frederick Van Rensselaer Dey to write over a thousand anonymous dime novels between 1891 and 1915 when Nick Carter Weekly changed to Detective Story Magazine.

Doyle wrote a mere four novels and 56 short stories, with the rare “action sequence” lasting about a sentence: “He flew at me with a knife, and I had to grasp him twice, and got a cut over the knuckles, before I had the upper hand of him.”New York Times film reviewer A. O. Scott labels Holmes a “proto-superhero,” one who’s “never been much for physical violence,” crediting the Downey incarnation for the innovation of making the detective “a brawling, head-butting, fist-in-the-gut, knee-in-the-groin action hero” (what one commenter called “The precise opposite of Sherlock Holmes”). The film opens with Downey in a bare-knuckled boxing match, displaying the skills Doyle only hints at. Apparently Holmes once went three rounds with a prize-fighter who tells him, “Ah, you’re one that has wasted your gifts, you have! You might have aimed high, if you had joined the fancy.”

Nick Carter, on the other hand, has the fancy: “He bounded forward and seized in an iron grasp the man whom he had just struck. Then, raising him from the floor as though he were a babe, the detective hurled him bodily, straight at the now advancing men.” Yes, in addition to all of Holmes’ sleuthing powers, Carter has superhuman strength. And a bit of a temper—the secret ingredient American producers feel is missing from all those stodgy British incarnations.

Jonny Lee Miller’s Holmes doesn’t hurl men like babes, but he has broken a finger or two sucker punching serial killers. The leap over the Atlantic has made the Elementary detective’s passions more violent than his London predecessors. He also has a tendency to wander onto screen shirtless, displaying tattoos and a well-curated physique. His drug problems seems to be a carry-over from his Trainspotting days, which means the English accent is as authentic as Cumberbatch’s. In fact, Miller and his BBC counterpart co-starred in a London production of Frankenstein in 2011. You’ll never guess who played the doctor and who the monster. Literally, you’ll never guess—because Miller and Cumberbatch swapped parts nightly. Mr. Downey was busy completing the sequel Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, and so was not available for matinees.

Plans for a Sherlock Holmes 3 have been in talks too, but Downey was busy with Avengers, Iron Man 3 and now Avengers 2. Why settle for a proto-superhero when you can play a real one? At least the long-delayed season 3 of Sherlock finally arrived. It was perfectly fun watching a barefoot and CGI-shrunken Martin Freeman chat with Cumberbatch’s growly dragon in Hobbit 2, but nothing beats the Holmes-Watson bromance—a delight the otherwise delightful Jude Law and Lucy Liu can’t quite deliver with their Frankenstein partners. Sherlock is also the last show my family still watches as a family, so I don’t mind the BBC cauterizing the Nick Carterization of the character.

Of course Nick has evolved since the 19th century too: a 30s pulp run, a 40s radio show, a 60s book series. I have the anonymously written Nick Carter: The Redolmo Affair on my shelf. It’s a musty James Bond knock-off I found in a vacation house and kept in exchange for whatever I was reading at the time. I can’t bring myself to flip more than a few pages: “I streamrollered my shoulder into his gut and sent us both crashing to the deck. I got my hands on his throat and started squeezing. His fist was smashing down on my head, hammering into my skull.”

In Nick’s defense, Doyle considered Sherlock Holmes schlock too. He hurled him over a cliff so he could stop writing his character—but the detective keeps bouncing back. Elementary is certain to be renewed for a third season, and the Sherlock season 3 finale is a cliffhanger with the next two seasons already plotted. The biggest mystery is how they’ll keep Cumberbatch out of a boxing ring.

Tags: Arthur Conan Doyle, Benedict Cumberbatch, Elementary, Frankenstein, Frederick Van Rensselaer Dey, Jonny Lee Miller, Nick Carter, Robert Downey Jr., Sherlock

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized