Monthly Archives: September 2015

28/09/15 About Last Night

Superheroes just want to settle down and get married.

Or at least they used to. Spring-Heeled Jack, Night Wind, Gray Seal, Zorro, Blackshirt, most of the pre-Depression pulp crowd eventually hung up their masks and retired into the domestic oblivion of happily everafter.

Or tried to. Until their readers and publishers and writers demanded sequels. But once you’ve closed the marriage plot, it’s hard to pry it back open. Fortunately the early pulp writers invented a utility belt’s worth of solutions, all still in use:

1) Poker Night.

Yes, darling, we’re married now, but I still have my manly pastimes.

Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel kept it up for decades. Ditto for Graham Montague Jeffries’ Blackshirt. Just one problem though. No more titillating romantic subplot. The hero is domesticated, all that manly excess bunched neatly into his briefs. For Frederic van Rensselaer Dey’s Night Wind, that meant promising his new bride to stop breaking the arms of police officers who foolishly got in his way. By the second sequel, the speedster superman was barely using any of his mutant powers, and his series quietly petered away.

Domestication has proved equally disastrous for modern heroes. The mid-90’s Lois & Clark: the New Adventures of Superman enjoyed stellar ratings, right up to the wedding episode, after which viewership nosedived and the show was cancelled. Marriage is kryptonite. Even Orczy and Jeffries had to switch to other family members (sons and ancestors) to keep their plots going.

2) Dial M.

Wife holding you down? No problem. Just kill her.

Thanks so much, Louis Joseph Vance, for introducing this heartless trope in the first of your seven Lone Wolf sequels. Though his 1914 gentleman thief had happily settled down with the law enforcement agent who lovingly reformed him, Vance dispatches her between books, mentioning her death in passing chapter one dialogue. When Hollywood adapted Robert Ludlum’s first Bourne Identity sequel, they made sure we got to witness the girlfriend’s death (Ludlum, in chivalrous contrast, only sent her off to stay with relatives.)

It’s a grim choice, but one that acknowledges narrative logic. For the superhero to marry, he usually unmasks and retires, and so ending the retirement also ends the marriage. Happily everafter is also a hard place to scrape up plot conflict. In 1973, when Marvel could no longer write around Spider-Man’s eight years of romantic contentment, they shoved his girlfriend off a bridge. Gwen Stacy (and the Silver Age of comics) died with a SNAP! of her too happy neck. Gwen’s 2014 death had a similar effect on the Spider-Man film franchise.

3) Groundhog Day.

Marriage? What marriage?

Johnston McCulley is responsible for the first superhero reboot. When Douglass Fairbanks donned Zorro’s mask and turned an obscure vigilante hero into an international icon, McCulley simply ignored the ending of his own novel when he wrote his first sequel. Zorro did not unmask, he did not retire, and he certainly didn’t run off and get married.

This solution remains annoyingly common. After two decades of marital bliss between Peter Parker and Mary Jane, Marvel signed a deal with the devil (Mephisto in the comic) and rebooted an unmarried Spider-Man in 2008. Like Zorro, Peter had also unmasked publicly, an event erased from the minds of all onlookers (but not, alas, all readers). Lois and Clark, who were married (like their short-lived TV counterparts) in 1996, suffered the same fate when DC rebooted their entire, romantically-challenged universe in 2011. In fact, the very idea of the reboot came from the editorial staff’s frustration with the Lane-Kent status quo and how its innate dullness prevented them from cooking up a new Superman love triangle.

However you handle it, marriage is hell on a writer. But the last solution is my favorite:

4) Perpetual Foreplay.

Frank Packard ended his first Gray Seal book with an implied bang. His proto-Batman waltzes off-stage with his superheroine girlfriend, unmasked nuptials to follow. But when bad guys and good sales returned the hero to active duty in 1919, the door to their bedroom bliss slammed shut. Since the Gray Seal’s do-gooding adventures were motivated not by revenge or altruism but superheroic lust for his bride-to-be, Packard needed to stretch out their romance plot. His four sequels offer increasingly frustrating reasons for why the lovers must remain divided.

Awkward as it sounds, Packard’s approach became the strategy of choice among 1930s pulp writers facing the titillating prospect of unlimited sequels.

Starting in 1933, The Spider magazine published a novella every month for a decade. Wealthy socialite Richard Wentworth fights crime as a costumed vigilante while also courting (and putting off) fiancé Nita Van Sloan. Norvell Page (writing under the house name Grant Stockbridge) tells us Wentworth must “sacrifice his hopes of personal happiness” because “the Spider could never marry,” could never “take on the responsibilities of wife and children” while continuing his crime-fighting mission.” Fortunately, Nita, like the Gray Seal’s would-be wife, is endlessly patient.

When William Gibson and Edward Hale Bierstadt adapted Gibson’s The Shadow for radio, they decided the lonely-hearted hero could use a fiancé too. The 1937 premier introduces Lamont Cranston and Margo Lane sipping coffee in his private library, as she begs him to end his career as the Shadow. He’d promised her as much five years ago when their courtship began, but Lamont, like Richard, feels “there is still so much to do” before he can settle down and unmask. “No, Margo,” he explains, “no one must know, no one but you.” And Margo, the ever dutiful (though ever jilted) help-mate, agrees.

But these women aren’t dupes either. They keep their own keys to the batcave. Nita is the Spider’s “best alley in the battle against crime,” “the one woman in the world who knew his secrets.” And Lamont calls the good accomplished by the Shadow “our activities.” Without Margo’s leg work, half of Gibson’s radio plots would stall.

But what other shared “activities” are these couple up to?

Page seems straight-forward enough: “Greatly they loved.” Nita and Richard (would you believe she calls him “Dick”?) share “pleasurable moments together,” though of course “all too brief.” How pleasurable? Page never penned a sex scene, but it’s clear Nina has access to Richard’s bedroom when she leaves him notes while he’s sleeping off a night of adventuring. As far as the Shadow, Alan Moore says it best in Watchmen: “I’d never been entirely sure what Lamont Cranston was up to with Margo Lane, but I’d bet it wasn’t near as innocent and wholesome as Clark Kent’s relationship with her namesake Lois.”

Since unmasking is the climax of the superhero romance plot, these lovers know each other in every sense. The marriage plots never technically closes, but pulp readers knew what was happening between the covers.

Tags: foreplay, jimmie dale, Lois and Clark, Margo Lane, mary jane, Spider-Man, superhero sex, The Shadow, The Spider, Zorro

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

21/09/15 The Talented Ms. Highsmith

Before meeting Alfred Hitchcock on a train to Hollywood fame, Patricia Highsmith wrote comic books. It was 1942, the height of the Golden Age boom, and a pretty good first job for an English major fresh from commencement. She started at the now largely forgotten Standard Comics but graduated to Timely (AKA Marvel) before leaving the field in 1948—when superheroes were dropping faster than Tom Ripley’s murder victims.

When she published The Talented Mr. Ripley in 1955, the comics market had been bludgeoned to near death by Congress and the Code. She had not been called to testify before the Senate because she had killed off the fact of her first career with a splatter of white-out. Comic books? What comic books? If outed by some sleuth of an interviewer, she might admit to having dabbled with Superman or Batman, but she had probably climbed no higher up the superhero pantheon than the Black Terror, a skull-and-bone chested knock-off since abandoned to public domain.

But for a highbrow author trying to bury her lowbrow past, Ms. Highsmith planted a lot of clues. Tom Ripley’s first victim (of tax scam, the murders come later) is a comic book artist who, Tom therefore assumes, “didn’t know whether he was coming or going.”He even knows that the artist’s “income’s earned on a freelance basis with no withholding tax,” making him an easy mark. Tom’s single real friend, Cleo, doesn’t draw comics, but “painted in a small way—a very small way”; her “imaginary landscapes of a junglelike land” were “no bigger than postage stamps” (like panels in a Thrilling Comics adventure perhaps?). Even Dickie, Tom’s first murder victim, is a painter, albeit a “lousy amateur,” though Tom pictures his pen-and-inks of ships as “precise draftsman’s drawings with every line and bolt and screw labeled.” Tom even takes up a brush himself, imitating Dickie’s mediocre smears.

As far as superpowers, Tom is an old school master-of-disguise. When defrauding that comic book artist, he becomes General Director of the IRS Adjustment Department, drawling “like a genial codger of sixty-odd” years. He wields an eyebrow pencil and a bottle of peroxide wash too, but knows a touch of putty on the end of his nose would be too much. The art of impersonation is a matter of mood and temperament, adopting just the right facial expressions and gait. Besides, he’d always “wanted to be an actor,” and after beating his would-be BFF with a boat oar and stealing his identity, he gets his chance. He even adopts Dickie’s flawed Italian, and of course his signature (“seven out of ten experts in America had said they did not believe the checks were forged”).

Highsmith is a mistress-of-disguise too. Comics were the least of the skulls and bones in her closet. After Hitchcock made her name by adapting her first, 1950 novel, Strangers on a Train, she published The Price of Salt as alter ego Claire Morgan. I’ve not read it, but I think Dr. Wertham and his buddies in the Senate would have cited Ms. Morgan’s sexual proclivities as further evidence of the unwholesomeness of the comics industry. Claire, like her creator, was bisexual, and, worse, dared to end her lesbian romance on a note of hope for her unrepentant protagonists.

Mr. Ripley has the same origin story. He’s stalked by the specter of his own homosexuality, repeatedly labeled “pansy” and “sissy” and “queer.” As a result, he can’t embrace any sexuality. “I can’t make up my mind whether I like men or women,” he jokes, “so I’m thinking of giving them both up.” But where does all that smoldering energy go? Blunt objects. His second murder weapon is an ashtray. The victim is a “selfish, stupid bastard who had sneered at” Dickie, “one of his best friends—just because he suspected him of sexual deviation.” When Tom was alone in a boat for the last time with Dickie (oh, don’t even start on the oar-sized penis jokes), he realized he could have “hit Dickie, sprung on him, or kissed him, or thrown him overboard.” The thwarted sexual impulse is steered into violence. For that tentative reason, I’m not appalled at Ms. Highsmith for ending her crime novel on a note of triumph for her unrepentant protagonist. Like Claire, Tom goes unpunished.

Or at least not legally punished. The damage he commits on himself is deeper. When forced to abandon his socialite existence as the gentlemanly Dickie, he “hated becoming Thomas Ripley again . . . as he would have hated putting on a shabby suit of clothes.” His former self, “Tom Ripley, shy and meek,” becomes just another performance—like the one a certain superpowered alien from Krypton adopts. He decides to “play up Tom a little more . . . He could stoop a little more, he could be shyer than ever, he could even wear horn-rimmed glasses and hold his mouth in an even sadder, droopier manner.” When Highsmith said she wrote Superman and Batman, she meant Clark Kent and Bruce Wayne, the ying and yang of her shapeshifting murder’s Tom and Dickie duality.

Superman and Batman make an appearance too. Yes, Tom fits the standard orphan model (“My parents died when I was very small”), but Highsmith pulls back her superhero mask even further as Tom stands aboard a ship, all but certain he’s finally to be arrested: “He imagined strange things: Mrs. Cartwright’s daughter falling overboard and he jumping after her and saving her. Or fighting through the waters of a ruptured bulkhead to close the breach with his own body. He felt possessed of a preternatural strength and fearlessness.”

In another, less homophobic universe, Mr. Ripley might have saved himself by using his considerable talents for good. Instead, he bludgeons the Comics Code established the year before he was published:

Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal

No comics shall explicitly present the unique details and methods of a crime

Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates the desire for emulation.

In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

And most importantly:

Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at or portrayed. Violent love scenes as well as sexual abnormalities are unacceptable.

Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden.

It’s enough to twist even Batman and Superman into sociopathic serial killers.

Tags: Black Terror, Claire Morgan, Ned Pines, Patricia Highsmith, Standard Comics, The Talented Mr. Ripley

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

14/09/15 What’s Funny About This Picture?

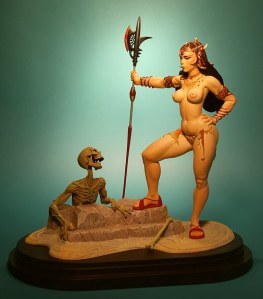

I was seven the first time I saw this illustration. I’d never heard of Frank Frazetta, but forty years later I still recognize the style. I assumed it was an Eerie or Creepy cover, but flipping through online databases and comic-con long boxes unearthed nothing. My memory had added a throne, so my description to vendors didn’t help either.

I knew it was early 70s because I’d seen it during a family vacation in Cape May, NJ. We went multiple years, but stayed only once in the Sea Mist Hotel–on the second or third floor, the right side, in what seemed like an improbably large open space.

An adult cousin–I don’t know which of my father’s nephews–was suddenly staying with us too. He’d arrived on a motorcycle and slept in a sleeping bag in his underwear on the floor. I slept in my briefs, but with pajamas over top, so his relative nakedness confused me, a change in the rules.

The magazine was his. It confused me too. It was sitting on a large table, more or less chin height, as I studied the cover at what must have been a distance of inches. It didn’t occur to me to open it or to pick it up. Though there was nothing taboo in its placement, no sudden parental shuffling of papers, I felt something transgressive. The breasts presumably. I’d seen my mother naked, but this was different, another shifting of known rules.

This was 1973, only months before my parents’ separation. I turned seven in June. Frazetta penned “72” next to his signature, but the magazine logo hides it. I had no idea he’d illustrated a National Lampoon until the cover popped up on my laptop during a recent Google search. No. 41, August, so on stands in July when my cousin grabbed his copy on the way to a beach getaway.

I’m still not sure what it’s doing on the front of “The Humor Magazine.” Frazetta drew the occasional Playboy-esque cartoon,

but “Ghoul Queen” is closer to the distortions of his fantasy style. Still, the ghouls are more comic than menacing,

and their queen’s hip-to-waist ratio exceeds even Frazetta’s usual idealized proportions.

An editor’s note claims he drew it for a previous “Tits ‘n’ Lizards” issue, but that’s just an example of the magazine’s “Humor.” Looking at the cover now, I’m still confused. Female nudity aside, the image seems to be about race. A white woman reigns over her dark-skinned minions. This could be the White Goddess and her African worshipers in 1931’s Trader Horn.

Instead of Aryan curls, Frazetta endows his goddess Asian overtones–or is that just make-up? This bejeweled yet rag-wearing Queen must spend a lot of time plucking her eyebrows.

Despite all the abundant white flesh glowing in front of them, the ghouls’ eyes are averted. The Queen is displayed for the viewer only. The image dramatizes the Mississippi racial rules that Emmett Till violated in 1955. A white woman’s body is always taboo to dark-skinned males, no matter how outlandishly posed.

Sculptor Tim Bruckner also suggests a homoerotic dimension to Frazetta’s sex fantasy: “having to decide what some of the ghoul pairs were doing behind her was something best left to the imagination.”

Are those expressions of monstrous pleasure? Are the obscured arms of the rear figures directed toward their crotches? Do the splayed fingers and curved wrists of the foregrounded hands denote submission? Does the apparent orgy explain their disinterest in the Queen’s body, or is this how dark males control their desire for white female flesh? And why the hell did Frazetta draw an extra left hand groping around her hip?

I see other anatomical issues (her face is too small, her breasts too round), but I’m more concerned with the ones I can’t see. Like her right leg. The pose suggests that the knee is bent so that the right calf is vertical, like so:

Except that space is occupied by a ghoul. The Queen’s leg isn’t hidden by his back–their bodies overlap as if collaged from separate planes. The two images don’t belong together. Maybe that’s why the ghouls aren’t ogling their queen, and why her gaze skirts past them too. It would also explain the floating hand. Frazetta was revising. The 3-D impossibility is further augmented by the two-dimensions of the image. It’s a painting, so obviously two-dimensional, but Frazetta emphasizes that fact by not filling the entire canvas. The sky behind the figures and the ground in front of them are the same continuous, unpainted space. He even flattens the vulture so its outlined body is almost as undifferentiated as the moon.

None of this struck my seven-year-old imagination. After an anxious glance at the Queen’s towering authority, my eyes dropped to the discordant subplot at the bottom of the page. The snake offers a range of mysteries (is it attached to the lizard’s head? what are those snail-like appendages?), but I was busy contemplating the two other figures.

I’m tempted to say this is the moment I first realized I was straight. But I didn’t realize anything. I just sensed something inexplicable. When I rediscovered the image online, I wasn’t sure it was the same–where was the throne?–until my eyes dropped to the skeleton’s hand again. I could feel it as if looking at a photograph of my younger self and remembering the sensations of the frozen moment. The dark-skinned ghouls and their domineering queen had nothing to do with me, but that skinless skeleton hungrily pawing an unconscious woman’s body, that’s who I identified with. That was me.

It’s not the cover image to my sexuality I would choose. It merges incompatible desires–is the skeleton’s mouth wide with arousal, or is he (“he”) anticipating a juicy meal? Either way, he’s a predator. Though not, apparently, a hunter. The woman is a discarded scrap, literally below the interest of the queen and her ghouls. Even the snake-lizard stares off indifferently as the woman’s face is obscured by its Freudian body. I understood her then and now to be unconscious, though she might as easily be dead. Perhaps her erect nipples signify living prey.

So my first inkling of sexuality was triggered by a fantastical representation of date rape. The girl’s been roofied. It’s a dire contrast to the Ghoul Queen–a woman commanding a gang of four grotesque but muscular males who have the physical ability to overpower her but instead bend and crawl at her feet (while possibly having anal intercourse). She is the painting’s largest figure, the tallest, spanning nearly the height of the frame, her figure embodying unchallenged authority. If not for the voyeuristic nudity, you might call her image feminist.

But then there’s the roofied girl, a depiction of abject weakness, the pose reducing her to a faceless and defenseless torso. The Queen’s power is positioned over this lower image, appears somehow predicated on it. While her impersonal eyes assess her ghouls, her imperial foot pins the unconscious girl’s hair. She is literally standing on her.

There’s a range of unstated narrative possibilities–does the Queen maintain power by sacrificing her Caucasian sisters to the dark horde? are only skinless and so racially unidentifiable ghouls allowed to fondle white flesh?–but the pose says enough. The girl is the Queen’s victim, not the other monsters’.

Why was my skeleton hand drawn to the unconscious girl’s breasts, but not the Queen’s? They’re smaller, so less intimidating? The Queen is equally exposed, but wholly in control of the fact. I can ogle her, but only because she seems to permit it, her chin angled invitingly away. But at any moment, those eyes could turn and gaze back at me. Did my seven-year-old bones inch across the roofied girl’s ribs because she has no eyes to see me? Did my memory fabricate a throne because a seated Queen is less horrifying?

Apparently Tim Bruckner was uncomfortable with these questions too. When he adapted “Ghoul Queen” into a 3-D miniature, he altered more than two dimensions. “It was important to pare down the composition to its essentials,” he said.

Non-essentials include ghoulish racism, slithering homophobia, and date-rape misogyny. But the skeleton remains–though not the nature of its now non-predatory hunger. “There’s nothing coy or retiring about a Frazetta woman,” explained Bruckner. “Even simply standing with a pike, her hand on her hip, being admired by one of the undead, she announces her presence with every sensuous curve of her body.” Bruckner literally turns my skull’s desire toward a stance of female power.

But I still wouldn’t choose the revised Ghoul Queen for my cover art. National Lampoon dubbed their issue “Strange Beliefs,” a better title for the painting too, though I doubt the editors knew they were lampooning American sex and racial norms. They presumably didn’t know they were lampooning me.

Tags: 41, August 1973, Frank Frazetta, Ghoul Queen, National Lampoon, Strange Beliefs, Tim Bruckner

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

07/09/15 Superman on Trial

Can reading detective fiction and Superman literature turn you into a supervillain? Super-lawyer Clarence Darrow says yes. He argued his case this week in 1924.

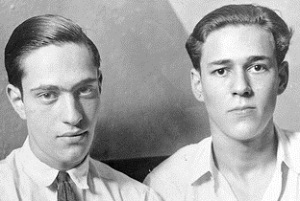

The facts were indisputable. His clients, Dickie Loeb and Babe Leopold rented a car, picked up Dickie’s fourteen-year-old cousin Bobby from school, and bludgeoned him with a chisel in the front seat. After stopping for sandwiches, they stripped the body, disfigured it with acid, and hid it below a railroad track. When they got home, they burnt their blood-spotted clothes and mailed the parents a ransom note. It was the perfect crime.

Dickie was nineteen, Babe twenty, but both had already completed undergraduate degrees and were enrolled in law schools. They were also both voracious readers. Darrow, their defense attorney, detailed Dickie’s literary tastes: “detective stories,” each one “a story of crime,” ones, he said, the state legislature had wisely “forbidden boys to read” for fear they would “produce criminal tendencies.” Dickie “devoured” them. “He read them day after day . . . and almost nothing else.”

Darrow didn’t mention any titles, but Dickie must have snuck stacks of Detective Story Magazine past his governess. The Street and Smith pulp doubled from a bi-monthly to a weekly the year he turned twelve. Johnston McCulley was a favorite with fans. His gentleman criminal the Black Star wears a cape and hood with an emblem on the forehead. So does his Thunderbolt. Darrow said Dickie’s pulps “all show how smart the detective is, and where the criminal himself falls down.” But the detectives chasing the Man in Purple, the Picaroon, the Gray Ghost, the Joker, the Scarlet Fox—they never catch their man. Those noble vigilantes remain safely outside the law. They are also all young men born into wealth who disguise their secret lives. So Dickie, the son of a corporate vice-president, learned to play detective, “shadowing people on the street,” as he fantasized “being the head of a band of criminals.” “Early in his life,” said Darrow, Dickie “conceived the idea of that there could be a perfect crime,” one he could himself “plan and accomplish.”

Babe was an impressionable reader too. He’d started speaking at four months and earned genius level IQ scores. Darrow called him “a boy obsessed of learning,” but one without an “emotional life.” He makes him sound like a renegade android, “an intellectual machine going without balance and without a governor.” Where Dickie transgressed through pulp fiction, “Babe took to philosophy.” Instead of McCulley, Nietzsche started “obsessing” Babe at sixteen. Darrow called Nietzsche’s doctrine “a species of insanity,” one “holding that the intelligent man is beyond good and evil, that the laws for good and the laws for evil do not apply to those who approach the superman.” Babe summed up Nietzsche the same way in a letter to Dickie: “In formulating a superman he is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern ordinary men.” A member of “the master class,” says Nietzsche himself, “may act to all of lower rank . . . as he pleases.” That includes murdering a fourteen-year-old neighbor as one “might kill a spider or a fly.”

So Babe considered Dickie a fellow superman. And Dickie considered Babe a perfect partner in crime. The two genres have one formula point in common: heroes are “above the law.” When Siegel and Shuster merged Beyond Good and Evil with Detective Story Magazine in 1938, they came up with Action Comics No. 1. Loeb and Leopold only got Life Plus 99 Years, the title of Babe’s autobiography. Prosecutors wanted to hear a death sentence, but Darrow wrote a modern law classic for his closing argument. It brought the judge to tears.

William Jennings Bryan liked it too. He quoted excerpts during the Scopes “Monkey” trial the following year. Bryan was prosecuting John Scopes for teaching the theory of evolution in a Tennessee high school, and Darrow was defending him. Scopes, a gym teacher subbing in science, used George William Hunter’s school board-approved Civil Biology, a standard textbook since 1914, and one that shocks my students when I assign it in my “Superheroes” course.

“If the stock of domesticated animals can be improved,” writes Hunter, “it is not unfair to ask if the health and vigor of the future generations of men and women on the earth might not be improved by applying to them the laws of selection.” After describing families of “parasites” who spread “disease, immorality, and crime,” he argues: “If such people were lower animals, we would probably kill them off to prevent them from spreading. Humanity will not allow this, but we do have the remedy of separating the sexes in asylums or other places and in various ways preventing intermarriage and the possibilities of perpetuating such a low and degenerate race.”

This was one of Bryan’s main objections to evolution, a term he used interchangeably with eugenics: “Its only program for man is scientific breeding, a system under which a few supposedly superior intellects, self-appointed, would direct the mating and the movements of the mass of mankind—an impossible system!”Bryan links eugenics to Nietzsche, as Darrow had the year before, saying Nietzsche believed “evolution was working toward the superman.” The claim is arguable, but the superman was “a damnable philosophy” to Bryan, a “flower that blooms on the stalk of evolution.”

“Would the State be blameless,” he asked, “if it permitted the universities under its control to be turned into training schools for murderers? When you get back to the root of this question, you will find that the Legislature not only had a right to protect the students from the evolutionary hypothesis, but was in duty bound to do so.”

Darrow declined to make a closing argument, preventing Bryan from making his before the judge too, so their final debate played out in newspapers. Either way, Darrow was talking from both ends of his ubermensch. “Loeb knew nothing of evolution or Nietzsche,” he told the Associated Press. “It is probable he never heard of either. But because Leopold had read Nietzsche, does that prove that this philosophy or education was responsible for the act of two crazy boys?”

Perhaps Darrow’s hypocrisy is an illustration of a superman only obeying his own laws. It didn’t matter though. Like Loeb and Leopold’s, Scopes’ guilt was never contested, and the court fined him $100 (later overturned on a technicality). That was 1925, the year the Fascist-inspired “super-criminal” Blackshirt joined Zorro and his merry band of pulp vigilantes, while Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf climbed the German best-seller list.

Superman was ascending.

Tags: Clarence Darrow, Detective Story Magazine, Leopold and Loeb, Nietzsche, Scopes monkey trial, William Jennings Bryan

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized