Monthly Archives: November 2018

26/11/18 Combining Words and Images

Scott McCloud categorizes seven ways word and pictures can combine to produce meanings that words or pictures alone can’t. Let’s instead focus on just three broader categories. Do the words and image: echo, contrast, or divide? Below are descriptions from published comics, followed by visual examples from our students.

If they echo, the two are in sync to communicate the same content in unison. Sound effects are an obvious example: the word “BANG” drawn inside the jagged lines of an emanata burst at the end of a gun barrel. McCloud might call that picture-specific, since removing the word doesn’t change much, but not word-specific, since “BANG” without the image of the gun could be ambiguous. He might also call it duo-specific if the image and words are just duplicating each other. Early superhero comic books were heavily duo-specific. In Batman’s first episode in Detective Comics #22 (1939), Bill Finger scripts caption box narration: “He grabs his second adversary in a deadly headlock … and with a mighty have … sends the burly criminal flying through space,” which Bob Kane’s drawings visually repeat. While there may be specific aesthetic reasons to have words and images echo at times, redundancy is generally a bad idea. Avoid it. If words and images convey the same content, the easiest solution is to cut the words. In fact, if words don’t add something unique and essential, always cut them. They’re crutches—or training wheels, a useful step in the creative process, but don’t let them get in the way later. Comics are first and foremost image-based. Trust the images.

Words and images can also complicate and even contradict each other through contrasts. In Sex Fantasy (2017), Sophia Foster-Dimino draws the words “I water the plants” beside a figure in a space suit and jet pack hovering above a row of various plants as she waters them from a device attached by a hose to her suit. While the image doesn’t contradict the words, it doesn’t match any of the expected images the words suggest on their own. In Was She Pretty? (2016), Leanne Shapton writes: “Joel’s ex-girlfriend was a concert pianist. He described her hands as ‘quick and deft.’ Her nails were painted with dark red Chanel varnish.” The accompanying image is a woman’s head looking over her shoulder in profile—presumably of Joel’s ex, who we see has long hair and bangs. McCloud might call this combination word-specific, since the image adds less than the words do, but the lack of overlap is intriguing. In contrast to the words, the image includes no hands and so no fingernails and no piano or anything else indicating a connection to music. The image might be understood as quietly disagreeing with the words, a visual counterpoint suggesting that Joel was focusing on the wrong qualities.

Other contrast combinations are sharper. In The Epic of Gilgamesh (2018), next to Kent Dixon’s translation: “they went down to the Euphrates; they washed their hands,” Kevin Dixon draws only Gilgamesh washing his hands but Enkidu diving into the water head first—implying that the text is so incomplete that it’s essentially wrong. In “Thomas the Leader” from How to Be Happy (2014), Eleanor Davis draws the main character angrily pinning and crushing the breath out his best friend, before pulling back and saying, “I was just kidding, Davey. It was a joke.” In Anya’s Ghost (2011), Vera Brosgol writes “See you, buddy” in a talk balloon above a frowning character who doesn’t seem to consider the other character a “buddy” at all.

Sometimes contrasts are ambiguous. The Defenders #16 (1974) concludes after the supervillain Magneto and his allies have been transformed into infants by a god-like entity. Scripter Len Wein gives Doctor Strange the concluding dialogue: “A godling passed among us today and, in passing, left behind a most precious gift! After all, how many lost souls are there who receive a second chance at life?” Penciller Sal Buscema, however, draws not just any children, but temperamental ones, their frowning, tear-dripping faces repeating the geometry of the adult Magneto’s shouting mouth from earlier panels. Because the images imply that the supervillains were always toddler-like in their immaturity, the babies appear innately bad, their inner characters unchanged by their outer transformations. The image contradicts Doctor Strange’s hopeful conclusion, creating a dilemma for the reader: which is right, the text or the image? The ambiguity may be a result of the creative process involving a separate writer and artist, but it occurs in single-author comics too. In Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home (2006), a caption box includes the text: “Maybe he didn’t notice the truck coming because he was preoccupied with the divorce. People often have accidents when they’re distraught.” The image underneath depicts Bechdel’s father crossing a road while carrying branch cuttings on his shoulder. Not only do his blank expression and relaxed posture not communicate “distraught,” the cuttings are blocking his view of the oncoming truck and so they, not his preoccupation with his divorce, are the visually implied reason for his not noticing the truck. Bechdel’s text stated earlier that her father “didn’t kill himself until I was nearly twenty,” the first reference to the memoir’s core event, and yet one undermined by the image five pages later. Again, who should we believe: Bechdel the prose writer or Bechdel the artist?

In the third possibility, words and images divide as if down unrelated paths, what McCloud calls parallel combinations. The text of Chris Ware’s six-page “I Guess” (1991) reads like a childhood memoir about personal incidents involving the narrator’s mother, grandparents, best friend, and stepfather—while the images depict a superhero story in the style of a Golden Age comic. More extensively, Robert Sikoryak’s book-length Terms and Conditions (2017) arranges the complete iTunes user agreement into word containers on pages based on other artist’s iconic work— Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, Allie Brosh’s Hyperbole and a Half, etc. Divided combinations can also eventually connect. In It’s A Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken (2004), Seth divides words and images for the first three pages. The seventeen panels depict the main character walking down a city street, entering a book store, browsing, finding a book, buying it, and walking down the street again. The text in black rectangles at the top of each panel describes how important cartoons have been to the narrator, with a detailed description of a specific Charlie Brown strip. If the words and images echoed each other, the book the main character is looking at would be a Peanuts collection. Instead, the narration reveals in the middle of the third page that “it was on this day that I happened upon a little book … by a Whitney Darrow Jr. I picked it up on an impulse”—a description that retroactively applies to the preceding dozen panels.

Divided combinations can also create double referents when words and images at first appear to reference the same subject before retroactively revealing a division. In Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá’s Daytripper (2011), the main character who has just turned down treatments for cancer stands in a jungle-like setting gazing toward an undrawn but brightly colored horizon—while circular word containers ask: “Did you have enough? Are you satisfied?” The page resolves with the realization that the containers are his son’s talk balloons, and he’s asking if his father would like more coffee as they sit at a backyard patio. Alan Moore is especially well-known for double referents. In his and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen #2 (1986), an opening panel shows a female statue in a cemetery with the words in caption boxes: “Aw, willya look at her? Pretty as a picture an’ still keepin’ her figure! So honey, what brings you to the city of the dead?” The word “her” appears to reference the statue, and “city of the dead” the cemetery–but in the next panel, the dialogue continue in talk balloons pointed at a woman addressing her mother in a retirement home—retroactively establishing the intentionally obscured references to the first set of words.

Here are examples of Leigh Ann’s and my students’ word-image combinations:

1) Coleman’s three panels all contrast. The first includes the narration, “I was very alone, and very tired, but I could not sleep,” with the image of a ceiling fan. It’s up to a viewer to connect the two by inferring that the image is the narrator’s view while lying on his back in his bed. Without that inference, the words and image are non-sequiturs. The second caption box contains: “She then ran into the kitchen while my brother and father were distracted.” The image of a cutting knife block is presumably an aspect of the kitchen, so not a contrast—except the text doesn’t mention that the mother ran into the kitchen in order to get a knife. That’s implied only by the empty knife slot. The third caption reads: “I met up with my brother and friend Dan down the street.” The hand lighting a joint is presumably one of the three characters, adding key information excluded from the narration, and so the image turns the words into a kind of lie of omission.

2) Katie mixes the unframed words “My doctors tried everything” with three images of her cartoon self lying in bed with an eye mask, receiving a shot in the neck, and wearing a neck brace. Though the words don’t mention those three actions directly, they appear to be specific examples of things the doctors tried. The images echo the words, while still providing additional information. While it’s possible that the images alone might communicate the content of the words, the combination also suggests that the list of things the doctors tried is longer than just the three included on the page.

3) Henry combines an image of pressure valves with the words: “If you participate, we’ll provide you with food and a place to stay.” Taken in context, a viewer would know that a corporate researcher is addressing a homeless man. Because the words are in a talk balloon pointing out of frame, we know the two characters are in the same room as the valves. A viewer will also likely assume the close-up isn’t a random aspect of the setting but one related to the request. The combination is contrasting because the connotation of the valves is nothing like the researcher’s positive assurances.

4) Daisy places the phrase “On our first date” in the top left corner of her panel and “she helped me file my financial statements” at the bottom right. Under the first phrase she draws manila folders, and above the second she adds a black bra—implying visually that the narrator and his date had sex. The words either omit this significant fact, or the image turns the statement into a metaphor for sex. Either way, the contrasting combination is effective.

5) Grace’s contrast is more extreme. Though the unframed words state: “The only way forward is to keep moving,” the character in the image is seated on a bench and so not moving forward. If the words are the character’s thoughts at that moment, the character becomes a kind of faulty narrator, apparently unaware of the contradiction. If the words are a third-person narrator’s or the pictured character’s narration looking back from another point in time, the words may read as an intentional critique of the character’s inaction.

6) Maddie draws her fish protagonist being accidentally stung by a jellyfish and exclaiming in a speech balloon, “Ow! That stings.” The words clarify the image content by echoing it. This level of redundancy is usually unnecessary and unaesthetic—except in children’s books, the genre Maddie’s comics is working in.

7) A later page of Daisy’s comics consists mostly of words. Before the couple introduced in the fourth example begins officially dating, the narrator hands her a contract to sign, saying in the circular, center panel: “You may want your lawyer to look this over.” The content of the contract legible in the background page panel is complex: “The Couple will make available their geolocation via the ‘Find My Friend’ iPhone application at all times, excepting instances in which revealing their location would compromise a pleasant surprise …” The extreme detail either supports the narrator’s advice or makes his advice an understatement. Also, his posture as he leans back in his chair at the opposite end of the table echoes the anti-romantic effect of the contract.

8) In Hung’s first panel, his main character’s hand reaches for a phone on a bedside table, and the second is a close-up of the phone screen, showing that the character’s mother has been calling and texting him for the past month without his responding. The words are both part of the story world and essential narrative content.

Tags: Alison Bechdel, Chris Ware, Dave Gibbons, Eleanor Davis, Fábio Moon, Gabriel Bá, Kevin Dixon, Leanne Shapton, Robert Sikoryak, Sal Buscema, Scott McCloud, Sophia Foster-Dimino, Vera Brosgol

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

19/11/18 Breaking New Ground in Nonfiction Graphic Novels

The term “nonfiction novel” was nonsense until Truman Capote coined it in 1965 to describe his In Cold Blood. “Nonfiction graphic novels” were still nonsense in 1991—until Art Spiegelman wrote to the New York Times asking why his best-selling, Pulitzer-winning Maus was listed under fiction: “I shudder to think how David Duke — if he could read — would respond to seeing a carefully researched work based closely on my father’s memories of life in Hitler’s Europe and in the death camps classified as fiction.” When the Times printed Spiegelman’s letter, they also moved Maus to their “hard-cover nonfiction” list, where it debuted at lucky thirteen.

In a sense, the literary genre of nonfiction comics debuted that day too. Not only did graphic memoirs begin to appear in the Times’ Book Review section, but also the even newer subgenre of graphic journalism pioneered most prominently by Joe Saco in the 90s. I was surprised at the time, but in retrospect it makes sense that a medium then-defined by flying men in tights would need to leap across genre lines to earn literary attention.

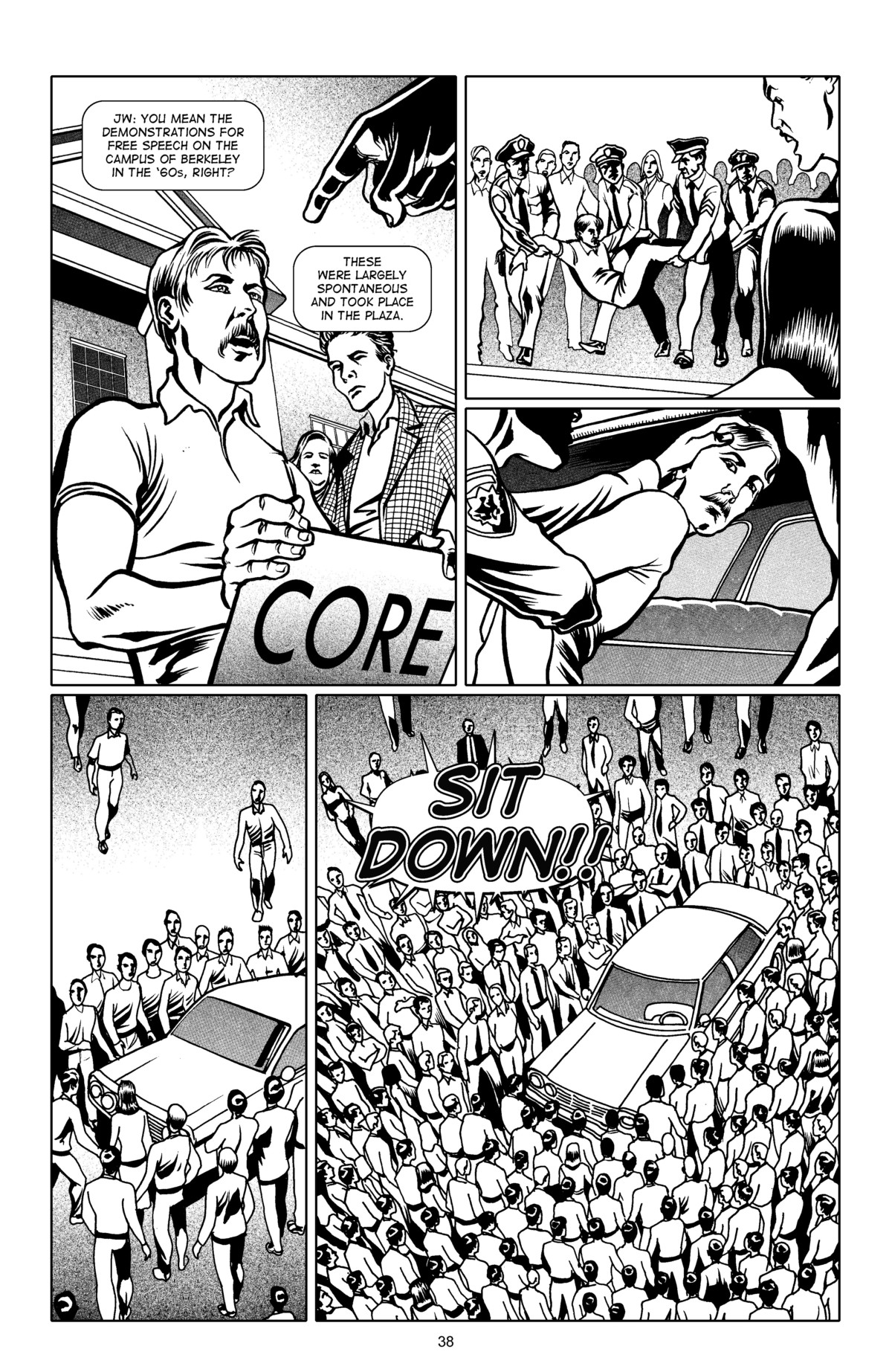

A quarter century later, nonfiction comics remain not only some of the most prominent in the field, but their range of “nonfiction” continues to expand too. Earlier this year the small press Seven Stories released Jeffrey Wilson’s The Instinct for Cooperation, intriguingly subtitled: “A Graphic Novel Conversation with Noam Chomsky.” As with Capote, “novel” doesn’t mean fiction here, since Wilson’s work is a well-researched, audio-recording-based merger of journalism and personal essay.

Like Kate Evan’s recent Threads, a first-person account of the refuge camps in northern France, Wilson casts himself as omniscient narrator leading readers through the tangents of his dialogue with the internationally renowned intellectual Chomsky. The transcript-basis of the comic also reminds me of Eleanor Davis’ recent, nonfiction-expanding You & a Bike & a Road, a drawn diary with a similar open-ended structure. Like Davis, Wilson had little control over his conversation once he hit record.

Of course Wilson didn’t decide to convert that conversation into graphic form until well afterwards, and his narration and chapter structure provides ample opportunities to escape Chomsky’s office and wind down other visual paths. Although his comic-book self hits record on page five, Wilson’s narrative voice is free to leap across countries and time periods, expanding on Chomsky’s references but also initiating other conversations. Three of the seven chapters leave Chomsky entirely to interview other people: students and teachers in Tucson, Arizona; volunteer librarians in New York’s Occupy Wall Street movement; an academic expert on student loan debt. It’s a smart approach, providing a wider range of both information and dramatic situations.

Wilson’s biggest challenge is the visually undramatic nature of his content: two guys at a table talking. Artist Wally Wood famously addressed this challenge in his 70s-era how-to graphic: “22 Panels That Always Work!!! Or Some Interesting Ways to Get Some Variety into Those Boring Panels Where Some Dumb Writer Has a Bunch of Lame Characters Sitting Around and Talking for Page After Page!” Wilson’s collaborating artist Eliseu Gouveia could add a few more to the list.

Gouveia’s computer-generated, black and white images are composed of sharp lines and graytones, in a naturalistic style that lightly echoes superhero comics. He captures Chomsky’s likeness well, but I had to read a page featuring the faces of Romney, Obama, Clinton, and Trump twice before recognizing the politicians, who go unnamed in the text. Wilson, who appears even more often than Chomsky, doesn’t include an author photo of himself for any ending comparison.

Though Gouveia’s panels are predominately rectangular, he accents key moments with tilts and overlays and the occasional frame-breaking flourish. The most visually engaging moments explore the physicality of Wilson’s interviews. When he attempts to phone a former Occupy librarian, their figures face each other across a zigzagging gutter as their speech boxes are interrupted by a faulty connection. After they switch to Skype, their eye contact across the now straight lines of the gutter is real, even though their locations are clearly unrelated—an effect ideally suited to the comics form.

Wilson’s conversations often center around the subject of spaces, how Occupy Wall Street both physically and organizationally structured itself in Zuccotti Park, combining a truly democratic system with the needs of, for example, a fully functioning library housed in plastic crates. I would have liked to see more visual interaction between the subject of such shared space and the literal page space, especially when the novel defaults to less engaging uses of words and images–as when Gouveia draws a jet above a map of the U.S. with an arrow indicating Wilson’s flight from Arizona to Massachusetts or a picture of a protestor’s hand-written agenda is followed by a picture of her stating, “Anything to add to the agenda?”

It’s impossible to know which visual choices are Gouveia’s and which were specified in Wilson’s script. Only Wilson’s name appears on the cover and copyright, and Gouveia’s “Illustrated by” credit on the title page falls under Wilson’s larger and bolded “Written by.” The Acknowledgements are Wilson’s only, and though he thanks dozens of people, including his parents, letterer Jay Jacot, and the 107 crowdfunders who supported the project, he does not mention his co-creator. According to the one-sentence, back cover bio, Gouveia is Portuguese—and may have never met Wilson in person, while executing his scripts for a contracted fee.

The arrangement wouldn’t be unusual, though in a work about cooperative relationships, not addressing it might be. The crowdfunding campaign alluded to in the Acknowledgements also seems to suit the theme of the interview, how strangers with common political agendas instinctually coalesce to aid each other. While the partial omissions don’t harm the graphic novel, it does seem Wilson may have ducked an opportunity to contextualize his work and link it more fully to his larger subject.

The novel is a wandering report on Chomsky’s thoughts on political organizing, initially focusing on Occupy, but soon veering to the Arizona legislature’s dismantling of a high school’s Latino studies program on the grounds that it promoted resentment against whites. The topic segues from New York’s destruction of the Occupy library—the way actual conversations are prone to shift abruptly. Other shifts follow Wilson’s line of questions, as when he prompts: “Professor, I would like to get your thoughts on the work being done post-Occupy? I’ve found especially inspiring the organizing around student loan debt with groups like Strike Debt and Rolling Jubilee.” Both the segue and the diction are a little stilted, an oddity in a transcript-based novel. Did Wilson really say things like “Occupy is a very interesting example of mutual aid, but are there other historical examples of this spontaneity?” in his interview or is his talk bubble speech overly condensed? Regardless, the leap from the Civil Rights protests in Greensboro and the armed uprisings in Barcelona in the 30s to Chomsky likening Wilson’s own student debt to “slavery” is jarring. I don’t disagree with Wilson’s advocacy, only its placement in the novel.

Conversations are by their nature unstructured, but the graphic novel strives for a level of organization that at times feels torn between the norms of a graphic essay and the openness of a free-ranging discussion. Still, Wilson breaks new ground, adding “graphic interview” to the expanding categories of nonfiction comics and introducing Chomsky and his political thoughts to a new audience of readers. Though The Instinct for Cooperation took Wilson several years to see into publication, I hope to see his next project sooner.

[A version of this post and my other recent comics reviews appear in the comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Eliseu Gouveia, Jeffrey Wilson, The Instinct for Cooperation

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

12/11/18 The Scifi Joy of Low-tech Comics Art

Founded just over a decade ago, Toronto-based Koyama Press has quickly become home for some of the quirkiest and most inventively successful comics on the market. Their release of Michael Comeau’s Winter’s Cosmos earlier this year is further evidence. This is the first graphic novel by Comeau I’ve read—and I suspect I’m missing a layered joke since “Michael Comeau” is also the name of a minor character in fellow Canadian cartoonist Bryan O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim series. The meta effect is appropriate since Winter’s Cosmos is a Moebius strip of self-reflective humor spoofing both science fiction and soft porn comics.

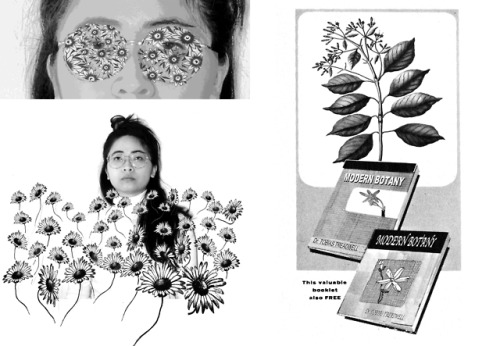

On its surface, the novel depicts two astronauts’ nine-year journey aboard the spaceship Sagitarii-Z to a distant planet in the Alpha Centauri constellation which they will begin transforming with seeds from Earth to ready for eventual colonization. But even that brief summary is misleading, since plot is the least of Comeau’s concerns. Most of the graphic novel depicts the nominal captain’s attempts to stave off boredom: he threatens suicide, he sexually harasses his lone crewmate, he watches porn, he boxes with floating droids, he sexually harasses his lone crewmate, he plays billiards with floating droids, he watches inexplicable videos about self-surveillance, he sexually harasses his lone crewmate—who shows endless, Vulcan-like indifference to his sophomoric prurience while getting off on Modern Botany books and conducting obscure but apparently mission-related work in her laboratory.

But again even that mostly plotless plot summary is misleading—because characterization is not Comeau’s concern either. The astronauts—Captain Jonathan Gerald Hoffstan and Dr. Tracy Anabelle Nguyen—are intentionally two-dimensional caricatures. If Winter’s Cosmos is about anything, it’s two-dimensionality—but not in the metaphorical sense. The graphic novel would not survive translation into another medium, say film or TV or stage or even an animated cartoon, because it is foremost about the paper that it’s printed on.

Comeau is a dizzying visual artist who relishes the cheapness of his images. His primary artistic tool appears to be a photocopier. Page after page of Winter’s Cosmos feature black and white reproductions of photos, cut-out images, and collaged printouts, combined and recombined for effects that would easily find a home in Andrei Molotiu’s ground-breaking 2009 anthology Abstract Comics. Two actors receive film-like credit for portraying the astronauts because Comeau uses actual photographs of the two posed in makeshift space uniforms which he pastes into computer-generated environments adorned with hand-drawn details. Their spaceship is a repeatedly reused stock photo of an 80s-era, U.S. space shuttle. Their equipment includes repurposed images of typewriters, telephones, and car engines that could have been torn from early 20th century catalogues.

The first sentence of the novel, “I’m gonna kill myself!”, appears in a talk balloon on page 12, but the four preceding double-page spreads feature a slowly transforming spacescape of grainy stars and planets resized and duplicated into a thickening pattern of black and white abstraction. That opening sequence sets the artistic tone for the rest of the book, which, even as the captain and the doctor limp through their lurid distractions, is filled with endlessly inventive visual variations framing and reframing the nominal plot. Though a reader can flip quickly through the novel for its sex-driven meta banter, a slower perusal is rewarding. I’m reminded of Talking Heads singer David Byrne’s comment: “Singing is a trick to get people to listen to music for longer than they would ordinarily.” If the promise of sex jokes is enough to trick people into opening Winter’s Cosmos, then they’re served their purpose too.

But while one venture into the captain’s favorite episode of “Puta Futura” may be entertaining, a second and third are less so. And while Comeau’s star-crossed couple can be read as a critique of traditional gender stereotypes—the sexually frigid intellectual female, the childishly sex-obsessed male—they mostly serve for quick gags that say nothing about the actual subject of sexual harassment that they overtly address. Comeau serves his readers better when his characters literally fade from view, and he directs our attention to the photocopied honeycombs of the ship’s engines or the medley of cubes and concentric circles that layer his idiosyncratic imaginings of outer space.

My favorite sequence is the novel’s last. After boredom has finally hobbled the captain’s brain, he believes he’s only in a simulator and (spoiler alert!) opens an airlock and spaces himself and the doctor. The last seventeen, wordless, two-page spreads unite the estranged characters in an atom-like configuration as the ship’s droids twirl around them like electrons. At the story level, their bodies appear to travel through a black hole and plummet to the surface of their destination planet which erupts into slow-motion plant life, fulfilling their mission to “fertilize” a new home for Earth. At the graphic level, the sequence fulfills the promise of the briefer opening as well as two other wordless visual sequences of the space launch and a later narratively ambiguous depiction of the ship’s engines. These moments are Comeau’s most visually involving, loosely motivated by narrative need, but grounded fully in the playfulness of his anarchic artistry.

If Winter’s Cosmos is Comeau’s Alpha Centauri, I look forward to what fruits his new planets will bear next.

[A version of this post and my other recent comics reviews appear in the comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Michael Comeau, Winter's Cosmos

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

05/11/18 Nude Descending an Escalator

In honor of the mid-term elections this week: here’s a three-figure blurgit of Donald Trump descending that damn escalator in the Trump Tower lobby way back whenever that was he announced his candidacy:

I almost named it “Descent” or “American Descent,” meaning into hell, but I prefer the reference to Duchamp. Of course, Trump is not–thank god–literally nude–he just always embodies a kind of brutal, ugly nakedness for me. The image is so distorted it’s almost opaquely abstract–which seems fitting too. It’s actually a digital photocollage incorporating these three video stills:

Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2” is based on a photo sequence too, one from Eadweard Muybridge’s 1887 Animal Locomotion:

Duchamp’s image is an art classic, but President Theodore Roosevelt hated it as an example of the “lunatic fringe” in early 20th century art:

“Take the picture which for some reason is called “A Naked Man Going Down Stairs.” There is in my bathroom a really good Navajo rug which, on any proper interpretation of the Cubist theory, is a far more satisfactory and decorative picture. Now, if, for some inscrutable reason, it suited somebody to call this rug a picture of, say, “A Well-Dressed Man Going Up a Ladder,” the name would fit the facts just about as well as in the case of the Cubist picture of the “Naked Man Going Down Stairs.” From the standpoint of terminology each name would have whatever merit inheres in a rather cheap straining after effect; and from the standpoint of decorative value, of sincerity, and of artistic merit, the Navajo rug is infinitely ahead of the picture.”

Roosevelt, like Trump, wasn’t a stickler for fact-checking little details like the actual name of Duchamp’s painting, but in Roosevelt’s defense, I doubt Donald Trump has any awareness of let alone opinions about early 21st century art, lunatic or otherwise. In my defense, I’ve been increasingly obsessed with Muybridge and recently created this Duchamp-esque variation:

As well as this male nude counterpoint, which I now find myself calling “A Well-Dressed Man Going Up a Ladder”:

As well as this male nude counterpoint, which I now find myself calling “A Well-Dressed Man Going Up a Ladder”:

But when it comes to Trump, I always picture him descending:

Descending and, if this isn’t a jinx on the mid-terms and the next two years, fading away. Here he is descending from that horrific Access Hollywood bus:

But I think a far more satisfactory and decorative descent will be from Air Force One, as Trump vanishes into a lunatic fringe chapter in American history books, becoming just a cheap straining after effect:

But I think a far more satisfactory and decorative descent will be from Air Force One, as Trump vanishes into a lunatic fringe chapter in American history books, becoming just a cheap straining after effect:

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized