Monthly Archives: September 2018

24/09/18 The Metaphysics of Emanata

Beetle Bailey cartoonist Mort Walker coined the term “emanata” in his tongue-in-cheek The Lexicon of Comicana (1980). It’s a noun form of “emanate” and refers to the cartoon lines that appear to emanate from objects. When the object is a head, they usually indicate some kind of internal experience, like the wavy lines that emanate from Peter Parker when his spider senses are tingling. Straight lines usually indicate surprise, though the same straight lines might mean shiny newness when emanating from, say, a Christmas present or loudness when emanating from a speaker or brightness when emanating from a lamp.

Only that last example is part of the visual world experienced by characters. The other lines are weirdly invisible except to the reader. Lines of sound emanata can be heard by a character and so are a kind of synesthesia, but surprise emanata are experienced only by the individual they emanate from. And this is all true despite the lines themselves being identical.

To explore that metaphysical weirdness, this week I’ve created a set of emanata lines arranged in a burst pattern and applied them to different photographs to test their effects. I think photographs are more revealing than drawings because the subject matter is instantly distinguishable from the emanata, while in most comics the two are both composed of the same kinds of drawn lines and so visually merged. I’m also using the emanata as a kind of scissors, creating white lines that strip away other content.

The first example is probably the most standard use, the rays of light emanata around the sun:

Walker calls those “solrads,” and though they represent an aspect of the visual world, light never actually looks like that. Solrads can also emanata from reflected sources, like the pool of light at this figure’s feet:

But even if you understand the emanata lines as representing actual light, they also and more prominently create a psychological effect, implying how strong and mighty that guy is as he strikes a superhero-saving-damsel pose.

The same can be applied to any object, creating the visual illusion of its radiating light, which is really a metaphor to suggest its importance. Here light literally seems to pour from a book, though probably you understand that light as the non-literal and so internal experience of the figure reading:

She’s illuminated by the light of knowledge. But those light-like emanata rays can apply to almost any experience. Instead of knowledge, try romantic passion:

Notice that even if you understand the kiss as positioned in front a literal rather than metaphorical sunburst, the psychological meaning still remains. Here’s another kiss, but I’ve reversed the burst lines so the center isn’t whited out:

It might just be me, but I no longer feel the emanata radiating away from the kiss but possibly moving toward it, like arrows of attraction converging at the greatest point of significance. I assume no one understands the emanata as being visible within the story world, but that’s not always clear. If the following image appeared in a superhero comic, you might understand the emanata as pulsing radiation, especially if the figure is about to transform into the Hulk:

But if the story were about a character experiencing pain, the same emanata would instead seem only metaphorical, the internal pulse of agony experienced only by the figure. Then again, maybe the figure has thrown herself on an exploding bomb? Then the emanata might indicate a range of senses: light, sound, and vibration.

By positioning the same emanata burst over a mouth, the sound becomes specifically a shout:

But only if the mouth is open. Place the burst over a closed mouth, and instead of sound the emanata might communicate power:

By placing it over this figure’s hands, the emanata burst has a romantic charge again:

This sequence of an identical hand creates the impression of energy being compressed:

And here’s one of the most standard uses of emanata in superhero comics, an impact burst:

I’ve also doubled and resized the photo to enhance the effect. Notice how the same technique applied to similar subject matters means something different if the center isn’t a point of physical contact:

Are those motion lines indicating that the two boxers are rushing toward each other or they arrows of importance indicating where the point of contact will be? Either way, emanata are some of the most versatile lines in a comics image, ones able to communicate an unlikely range of nuanced meanings.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

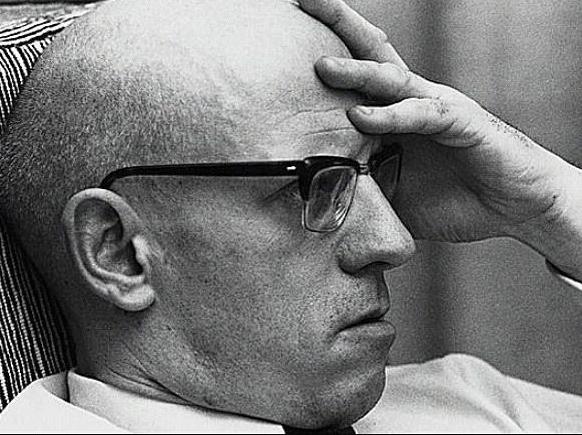

17/09/18 Foucault Comics

Comics are supposed to be funny so I’ll start with a punchline:

“A comics page is a panopticon atop a heterotopia.”

If that sounds like the least funny joke ending ever, here’s the beginning:

“A superhero, a French philosopher, and a prisoner designer walk into a bar.”

Or maybe:

“Batman, Michel Foucault, and Jeremy Bentham walk into a bar.”

Except there’s no bar. It was an email from an academic journal asking me to peer-review an article submission. I almost said no–does anyone really need to hear my opinion about a Foucaultian reading of the batcave?–but then I started writing a reader’s response in my head, gently critiquing the article for not addressing the formal qualities of the comics and their relationship to Foucault’s ideas. I didn’t actually know the author didn’t do this; it was just my very strong guess based on the abstract. So if only to satisfy my curiosity, I clicked ACCEPT and started reading.

Yep, no formal analysis. This is (to me) surprisingly common: discussions of comics that explore only their literary (textual and narrative) content while ignoring their visual qualities. It’s probably a result of comics studies growing out of English departments instead of Art departments–where comics are still struggling for a foothold. And in this case, the theoretical framework seemed especially well-suited to the comics form–so much so that Foucaultian interpretations started popping into my head.

I’m not a particular fan of Foucault, and certainly no expert, but here’s my first draft of panopticomix theorizing.

First, the panopticon. Since surveillance cameras were not a late 18th century option, Jeremy Benthan designed circular prisons that gave a single watchman the ability to observe an entire complex of cells from one location. The term roughly translates “all seen.”

![]()

Foucault analyzed the panopticon as an embodiment and a metaphor for institutional power in his 1977 Discipline and Punishment. He begins by describing a parallel system for how a city copes with a plague threat: “First, a strict spatial partitioning” producing an “enclosed, segmented space, observed at every point.” The prison panopticon achieves similar results architecturally: “The panoptic mechanism arranges spatial unities that make it possible to see constantly and to recognize immediately.” It also works regardless of who sits at the center: “Any individual, taken almost at random, can operate the machine.”

A comics page is a similar kind of visual system, one operated by a single viewer positioned in front of its multiple panels, or “cells.” Like a prison guard, the viewer perceives the range of available angles, while attending to only one at a time. Unlike a film audience, the comics viewer is in control, speeding up, slowing down, backtracking, and pausing at will. Prose readers have a similar degree of control, but prose is not subdivided into units as discreet as conventional panels. Framed art in a gallery exhibition is similarly subdivided, and the viewer does have similar control, but the gallery viewer must move to take in all of the art. In contrast, comics viewers, like panopticon watchmen, are stationary.

Foucault also discusses his own term “heterotopia,” literally “other world,” which further relates to the comics form. He writes in 1967:

“The present epoch will perhaps be above all the epoch of space. We are in the epoch of simultaneity: we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of the near and far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed. We are at a moment, I believe, when our experience of the world is less that of a long life developing through time than that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein.”

He outlines six characteristics, two of which are especially applicable: “The heterotopia is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible,” and “Heterotopias are most often linked to slices in time.”

A comics page, the blank and so typically white background on which panels are superimposed, functions similarly. While existing outside of the spatiotemporality of the story world contained in the panel images, the gutters–the typically undrawn white space that is the page background visible between panels–are how comics arrange and juxtapose the images that create their stories. The content of each panel is spatially incongruent, with each displaying a different slice of story time, but the gutters and margins of the (seemingly) underlying page allows them to function together.

Foucault later writes that hetertopian spaces “have the curious property of being in relation with all the other sites, but in such a way as to suspect, neutralize, or invert the set of relations that they happen to designate, mirror, or reflect.” Those relations are the comics panopticon, the layout of panels that is orderly and understandable–but only because it appears to be superimposed onto a non-place, the undrawn and literal negative spaces that allow the spatiotemporal progression of the panel images while existing outside of their logic.

In comics, the “other world” encloses the “all seen.”

Now consider French comics theorist Thierry Groensteen in The System of Comics:

“What is put on view is always a space that has been divided up, compartmentalized, a collection of juxtaposed frames, where, to cite the fine formula of Henri Van Lier, a “multi-framed aircraft” sails in suspension, “in the white nothingness of the printed page.” A page of comics is offered at first to a synthetic global vision, but that cannot be satisfactory. It demands to be traversed, crossed, glanced at, and analytically deciphered. This moment-to-moment reading does not take a lesser account of the totality of the panoptic field that constitutes the page (or the double page), since the focal vision never ceases to be enriched by peripheral vision.”

While Van Lier’s lyric description of a white nothingness that suspends but is not part of the compartmentalized content echoes Foucault’s heterotopia, Groensteen’s “synthetic global vision” and its continuous reliance on the viewer’s “peripheral vision” is the key to Benthan’s prison design. And of course Groensteen uses the adjective “panoptic” (or, like Foucault, the French equivalent).

Since Foucault’s panopticon focuses on the state’s system of power and discipline, a full Foucaultian application to the comics form would involve an analysis of the viewer as operating a system designed to give her power over the page’s partitioned content that she maintains in a fixed peripheral relationship as she inspects individual panels. The viewer is especially empowered since the comics form’s juxtaposed images co-produce inferences in her thoughts that allow the static, isolated images to flow as a narrative. The orderly power of the comics page then is also dependent on undrawn and so unviewable story events that emerge from the murky non-place of the gutters. The all-seeing panopticon layout paradoxically requires the unseeable heterotopia of the page background.

I could go on about prison bars and the bars of a comics grid–while circling back to the bar that Batman, Foucault and Bentham were walking into.

But I think you get the picture.

Tags: comics theory, heterotopia, Jeremy Bentham, Michel Foucault, panopticon, Thierry Groensteen

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

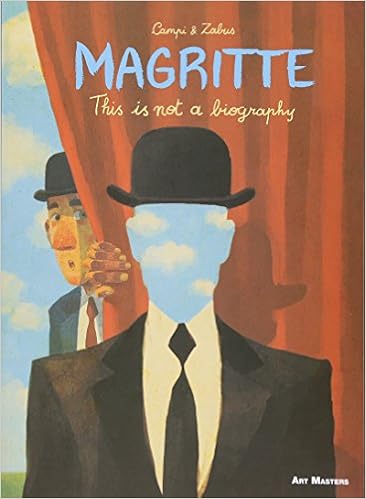

10/09/18 Magritte: This is not a Biography

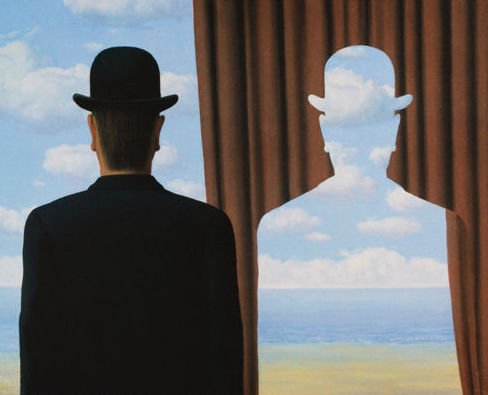

Rene Magritte is an ideal subject for a graphic novel. His paintings explore the same terrain that the comics form is built on, one that writer Vincent Zabus scripts into a Twilight Zone adventure for artist Thomas Campi to explore in his own surrealist variations.

Campi’s cover for Magritte: This Is Not a Biography recreates one of Magritte’s self-portraits in which the painter appears to have cut out the shape of his own head to reveal not the curtain behind him but the clouds behind the curtain. The layered illusion heightens both the appearance of depth in the painted image and yet also the flatness of the two-dimensional canvas. That kind of illusion runs through a range of Magritte’s paintings. It is also the defining illusion of comics.

Like the vast majority of comics artists, Campi places rectangular panels on the white backdrop of each page, creating the impression of windows that look into three-dimensional scenes situated just beyond the panel frames.

If a panel’s image includes a white object—a cloud, a wall, even the letters of captioned narration—that white is understood to be different from the white of the page visible between panels, even though both are literally identical. And while a comics page is like a gallery wall of independent paintings, it also combines its panels into layouts that emphasize page unity.

Campi, like Magritte, exploits these weirdnesses, at one point drawing a figure who not only breaks panel frames, but even appears to climb their edges like scaffolding. Zabus’s story is a kind of scaffolding too, giving Campi a narrative structure to hang his Magritte-inspired watercolors and oil paintings. Charles, Zabus’s stereotypically straight-laced narrator, accidentally dons what turns out to be Magritte’s bowler hat and so stumbles into an alternate universe fueled not only by the painter’s images but his personal history, allowing Zabus to sprinkle the nominal plot—will Charles ever escape this strange world?!—with a range of biographical facts, the way Campi sprinkles the same pages with visual references to Magritte’s art.

Zabus’s title echoes probably Margritte’s most famous work, The Treachery of Images, a painting of a pipe with the French words for “This is not a pipe.”

While the pun is entertaining, the resulting not-a-biography is also a not-an-entirely-engaging-story. It is difficult to care about the cartoonishly drawn Charles or his less cartoonishly drawn love interest, a Magritte expert he conveniently meets during his mission to comprehend the artist and so be allowed to remove his haunted hat. Arguably, that story is of secondary importance, but it occupies as much if not more page space than the cut-outs of Magritte’s life it indirectly provides.

At some level Zabus is lampooning the idea of biography, that it is even possible to encapsulate a person’s life events and psychological complexities. That partly explains Magritte’s two-dimensional characterization and stock summaries: “He was a sort of instinctive anarchist, a wild man who liked to play the dandy,” or “As a teenager, Rene was racked by a hyperactive and tortured libido. It was Georgette who channeled his urges, lent his incoherent life structure.” Yet when Charles exclaims, “The more I learn about Magritte, the more complicated he seems,” the opposite seems true. At times it seems Zabus is simplifying Magritte for a young audience, as if the graphic novel is targeting a children’s market, but the occasional nude breasts and one of Magritte’s few bits of dialogue, “The artist will now fuck his model!” eliminates that possibility.

The book’s best moments are its most playful ones, as when Magritte’s “biographer” appears as a tiny man on a miniature train and Charles complains, “The font’s too small. I can’t hear you,” or when the biographer dies of an arrow wound even as he acknowledges that his blood is only paint—which of course it literally is. The meta approach predictably places the book itself into the story, with an unnamed character reading a copy and warning Charles what will happen on the page’s bottom panel. Although he does eventually remove the bowler hat and escape Magritte’s world, Charles then chooses to abandon his normal life and reenter the novel’s final painting to float hand-in-hand with his beloved Magritte expert.

Happily, the actual book does not end there, but with several pages of additional paintings by Campi. Though Charles still appears in them all, Campi is finally free of Zabus’s dialogue and plot structure. This is perhaps the freedom that Charles and Magritte himself longed for too. As Zabus has Magritte say earlier in the narrative: “Like my paintings, do you? Then look at them! There are no answers, you know! Just images…”

While the not-a-biography approach is more entertaining than a standard biography, Zabus and Campi might also have explored other not-a-story approaches too, ones that might further realize the spirit of Magritte’s paintings by unlocking them from a conventional narrative structure. Still, the graphic novel’s overall playfulness, especially its visual riffs on Magritte’s paintings, is a fitting tribute to the artist, and one perfectly suited to the comics form.

[A version of this post and my other recent comics reviews appear in the comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Thomas Campi, Vincent Zabus

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

03/09/18 My Colonnade

My university’s website includes the timeline “African Americans at Washington and Lee.” The 1826 entry begins:

“Jockey” John Robinson dies and leaves his entire estate to Washington College. An Irish immigrant who had himself been an indentured servant, Robinson had amassed a considerable fortune as a horse trader, whiskey distiller, and plantation owner. He lived on about 1,000 acres of land at Hart’s Bottom, which would become the site of Buena Vista. Proceeds of the bequest, which was nearly as large as George Washington’s gift of canal stock, included “all the negroes of which I may die possessed together with their increase shall be retained, for the purposes of labour, upon the above Lands (Hart’s Bottom) for the space of fifty years after my decease.”

A trustee’s letter lists “between 70 & 80 negroes worth at a very low estimate forty thousand dollars.” A lawyer advised selling the land and enslaved people, despite Robinson’s explicit directions not. So in 1836:

“the Washington College trustees conclude “a sale of negroes to Samuel Garland” of Lynchburg, Virginia, Garland co-owned a plantation in Hinds County, Mississippi, and indicated that he planned to send the slaves there. In addition to the approximately 55 enslaved people it sold to Garland, the college also sells five other slaves to individuals in Lexington and Rockbridge County and retains six men and one woman.”

Robinson isn’t mentioned again in the timeline until 2016 when:

“the University formally introduced a historical marker, “A Difficult, Yet Undeniable, History,” recognizing the enslaved men and women owned by Washington College in the 19th century. The marker is located in a memorial garden between Robinson and Tucker halls. It includes the two lists of those men and women who were bequeathed to the college by John Robinson.”

The timeline has not been updated to include the creation of the Commission on the Institutional History and Community in August 2017, the release of the Commission’s Report last May, or our president’s official response to it last week. One of the Commission’s thirty-one recommendations was:

“Re-name Robinson Hall immediately. The hall’s association with slavery at Washington College – i.e., that the Robinson bequest included enslaved persons who labored at the institution until the institution sold them to others – gives special urgency to this proposal.”

The president did not respond to this recommendation. He only responded to the Commission’s recommendation to rename and repurpose Lee Chapel as a museum no longer used as a gathering place for school events. Even as he rejected it, he acknowledged its rationale:

“Others experience [Lee Chapel] as an exaltation of the Confederacy that divides us by making some members of our community feel unwelcome… Those concerned about the symbolism of the chapel object that the recumbent statue and the portrait of Lee in uniform make it difficult to participate fully in the life of W&L without also feeling that one is worshipping at a shrine of the Confederate South.”

Instead of converting the chapel to “a teaching museum in which no other university activities would occur,” our school will hire a new a Director of Institutional History, whose duties will include “making it clear that university assemblies, which would continue to take place in the chapel, have nothing to do with venerating the Confederacy.” I presume this new administrator will also be in charge of eventually responding to all of the other recommendations, including those of special urgency.

When the president responded to the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville last year by creating a committee to study the issues for an academic year, I tried to be optimistic. As he told the Washington Post last October: “I haven’t put any constraints on what the commission can think about, talk about, or recommend.” He also said: “People are all very eager to take action, and to know what action is going to be taken. I think the most important action is to spend some time learning and thinking.” I suspect that comment was in part a sub-tweet at my department. As the Washington Post article explains:

A month after torch-bearing white supremacists marched at the University of Virginia, some members of the English department at Washington and Lee took their own stand. “This community has profited by slavery,” they wrote online. “We are complicit in its harms.”

The college, they wrote, “is named after two slaveholding generals with powerful legacies. . . . If it were ever right to celebrate the contributions of Robert E. Lee as an educator, that time is past. Lee’s primary association, to many Americans and across the world, is with white supremacy.”

That prompted heated backlash.

The release of the Commission’s Report has prompted even more. Outraged alums have been threatening to cut off donations. One of the more eloquent wrote:

“As I suppose is the case with most of our alumni, I strongly oppose the most radical of the recommendations: the renaming and repurposing of Lee Chapel. I believe such a move would be a grave error, one that may do irreparable damage to the university, dramatically altering its future, and one which may have potentially devastating financial consequences as current and future donors reassess their willingness to support an institution that has sacrificed its traditions and history in favor of political expediency and moral signaling.”

Others have been less eloquent. Members of the Virginia Flaggers commented on their Facebook page:

“Leave the chapel alone! That committee needs to be disbanded for trying to have it removed”

“Remove comitee fanatics comunists”

They also applauded the president’s decision:

“Thank you, Mr. Dudley!”

“Gonads still exist.”

“God answered my prayers.”

“It shall ALWAYS be a CONFEDERATE SHRINE. All that General Lee honored with his service is hallowed ground.”

Our president has also consistently stated that his top priority is to increase student and faculty diversity. According to collegefactual. com:

Washington and Lee University is ranked #2,235 [out of 2,718] in ethnic diversity nationwide with a student body composition that is below the national average.

82% of students are white, and 85% of faculty are white. It would seem that having the name of the leading Confederate general in your institution’s name and his tomb at the metaphorical if not geographic heart of your campus isn’t an attraction for nonwhites. Perhaps worse, it likely is an attraction for individuals who agree with or at least are willing to overlook the racial ideology of the Confederacy.

Creating a commission to study problems and recommend solutions and then rejecting that commission’s most prominent recommendation while putting off discussion of all of its other recommendations–what kinds of prospective students and faculty members will those actions attract? What kinds will they repel?

We’ll have to wait to see how the “African Americans at Washington and Lee” timeline continues.

Meanwhile, I made the six-panel comic “My Colonnade” over a year ago. Like most comics, it doesn’t suffer from subtlety. It features a cartoon (meaning a highly simplified rendering) of W&L’s historic colonnade constructed over and incrementally obscuring an excerpt from a 1836 document describing the deaths of two of the enslaved people bequeathed to the college. Robinson Hall is on the right. My office window is behind the pillars on the left.

I had hoped that a year after Charlottesville this comic would be too dated to post here.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized