Monthly Archives: May 2019

27/05/19 Don’t Read This Comic (Look at it Instead)

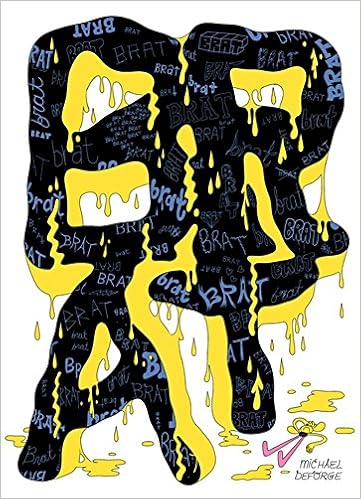

Sometimes I think I’m reading Michael DeForge the wrong way. His Instagram strip Leaving Richard’s Valley is out as a book collection from Drawn & Quarterly, but I’m catching up on Brat released last fall from Koyama Press. It’s a story of an aging celebrity, a former juvenile delinquent still renown for acts of vandalism appreciated by her now middle-aged followers as art installations. But I’m not sure “story” is the best word to describe the graphic narrative. Or rather it’s one perfectly accurate description that might accidentally obscure what’s most interesting about DeForge’s art.

At one level, Brat is simply a cartoon—albeit an extreme one. While all cartoonists simplify and distort natural proportions, few stray quite so far from recognizable anatomy. Charles Schultz’s Peanuts characters have impossibly large and round heads, an effect further exaggerated in Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s South Park cast. The character Brat’s head is large and round too—at least five times larger than the tiny circle of her torso, with pipe-cleaner-like limbs extending almost tenfold. If any other male artist drew his female protagonist in a nude shower scene on the second page of a comic, I would worry, but there’s not even the most remote element of eroticism here. While still somehow registering as “human,” the level of abstraction breaks even the most expansive norms of cartooning.

That abstraction applies to the rest of the story world too. While DeForge is capable of drawing geometric depth, complete with multiple planes and vanishing points, he prefers flat surfaces that evoke while also rejecting the illusion of three-dimensional space. Sometimes he combines the approaches for discordant effects. As Brat spray-paints the cascading walls of a building complex, the street beyond features solid red vehicles above a grid of sidewalks squares. Not only is the 90 degree angle entirely flattened, the cars look like stenciled cut-outs reduced to their absolute minimal shapes. Any further reduction and they would cease to represent anything at all.

While dimension-deforming environments are another norm of cartoon worlds, few wander this far to the edge of pure abstraction—let alone cross it. When I say I’m reading Brat the wrong way, it’s because I’m spending too much time actually reading. DeForge’s layouts are traditional grids, most often 3×2 with a range of full-page and other variants to give the reading paths some visual rhythm. Most panels also feature a cluster of words, usually in a talk balloons as characters converse or Brat’s monologues break the fourth wall. Both acts—following a sequence of images and decoding written words—are considered “reading” when it comes to comics, often with an emphasis on the literal, word-focused sense. That’s also usually where “story” happens. And DeForge supplies plenty of that—Brat torches a police car, Brat reads her fan mail, Brat shits on the floor—but there are other kinds of stories on these pages too.

As I wandered deeper into the story-world narrative about the narcissistic crises of a still-profitable has-been depressed by her nostalgia-driven fanbase, I found myself more interested in the surface qualities of the images themselves—how the identical black dots of Brat’s eyes and nose shift within the panel frames, or how an x-shape of a cat wraps itself around the column of Brat’s nominal leg, or how two figures move through a landscape of … are those clusters supposed to be stars or tumbleweeds or just random shapes? When the young Brat narrates in a flashback, her body’s tiny shapes occupy only a fraction of panels that alter color with each iteration. The colored squares do not represent the actual colors of walls or anything else in the story world. They’re just squares of color arranged on the surface of the pages. Even their sequence breaks down since there’s no narrative logic to which color appears when in the story and so where on the page. The effect is closer to one of Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe grids than to visual storytelling. It’s just abstraction.

And what would happen if there weren’t any words? The back of Brat’s head—two yellow swaths above a black semicircle–is visually undecodable out of context. Many of these panels would lose all representational meaning. DeForge is of course fully aware and manipulating these effects, and some of the book’s strongest episodic sequences take full advantage of them. “Tantrum,” for instance, begins with Brat crying and swearing as her body warps into even more impossible proportions, deeper distortions of her already cartoonish distortions. In “Hi Mom,” the figure of Brat’s crying father bends and merges with her mother until the two are a single yellow pyramid. “Immodest” features Brat’s drunken form devolving into squiggly shapes and then retracting into single lines before shrinking into literally nothing. While the images do nominally represent events in the story world—she’s depressed, she’s drunk—the “story” is about the shifting relationships of shapes on the page.

There’s plenty more of the conventional kind of stories too–a fling with an interviewer, the corruption of an intern, a kidnapping, various more meltdowns—but while each is entertaining, the bigger conceptual picture and its baseline pseudo-reality of extreme abstraction is the novel’s main strength. Because comics are traditionally understood as literature rather than art, and so are “read” rather than viewed, it’s possible to appreciate Brat as just a fun riff on a comically and nihilistically self-involved performance artist-criminal twirling through a sequence of chaotic plotlines. But that requires looking not at but through the images, attending less to their actual qualities, and understanding them primarily as symbols and so almost as words that represent events in some other far-off place and not as arrangements of ink on the physical pages in your hands.

While DeForge offers both kinds of stories, Brat is at its playful best when viewed rather than merely read.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Brat, Koyama Press, Michael DeForge

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

20/05/19 Why I Shouldn’t Be Fired for Teaching Comics

Last week I received a copy of a document titled “The ‘Dumbing Down’ of the Curriculum at W&L.” It begins:

“Over the last several years, a number of courses have been added to the curriculum which seem of dubious academic value, dedicated to the espousal of a political agenda, trivial, inane, or some combination of the above. A review of the current catalogue by departments is revealing.”

It then lists twenty courses beginning with: “1. Creating Comics- English Department,” followed by “2. Superheroes (i.e. comic book characters)- English Department.”

Both of those courses are mine.

Creating Comics is a hybrid creative writing and studio arts course that I conceived and co-teach with Leigh Ann Beavers in the W&L Art department. We have offered it during two spring terms, in 2016 and 2018, and we intend to offer it again in 2020. Leigh Ann and I are also under contract with Bloomsbury press to produce a textbook developed from our course. Superheroes was originally an English course that I taught at the request of a group of honors students in 2008, and it is currently the topic of my first-year writing seminar, which I typically teach each spring. Presumably because the document was dated November 2018, it does not include a course I taught this last winter, Introduction to Graphic Novels.

After the course list, the document asks:

“Do we really need classes in comic books with so much great literature to study … Would it not be possible to save money by eliminating some of these courses and eliminating some of the professors who teach them? Such questions should at least be asked and considered.”

I agree that questions should be asked and a wide range of answers considered. This is the core of my teaching philosophy. Students in all three of my courses mentioned above write interpretive questions in response to reading assignments, which then become the focus of discussion during the next class meeting. The open-ended, student-focused approach encourages a wide exploration, which sometimes results in consensus but more often reveals differences of interpretation grounded in textual evidence.

The document’s next two listings, “3. Literature, Race, and Ethnicity- English Department” and “4. Representations of Women, Gender and Sexuality in World Literature- English Dept.,” is more representative of the overall list, drawing the criticism:

“As in many other colleges, many of these courses seem to exist to meet the ever narrowing and increasingly politicized specializations of the professoriate. This is reflected in the increasing number of course which focus on race, gender, class, etc. … Surely, these topics would arise naturally without having whole classes dedicated to them.”

Ironically, I had considered naming my first-year seminar “Race, Class, Gender, and Superheroes,” but decided against it since I have found that those topics indeed do arise naturally. When I last taught the course in fall 2018, I was struck by how consistently my students focused on gender analysis, returning to it even after I attempted to nudge conversation to other, equally important topics.

So while my position in the list’s top two slots appears only to reflect the authors’ concerns about the “trivial” and “inane,” I suspect they would also fault me for what they imagine to be “the espousal of a political agenda.”

All three assumptions are incorrect.

I have written previously about the apolitical nature of my classroom (“How Not to Help Your Tenure Case”), which I will excerpt here:

“teachers should not abuse their positions by expressing their personal opinions to students who have no choice but to listen and would be wise to at least feign agreement with the person grading them. … Instead of expressing my opinions, I spend most of my class time encouraging my students to express theirs, and then only on the course-related topics that are the focus of our discussion. I encourage them to support their opinions with evidence. I urge them to disagree and to be persuasive but also to be open to changing their minds when someone else presents ideas and evidence they hadn’t yet considered. Does that make my classroom a production facility for Democratic beliefs and Democratic ideology? Only if Republicans are ideologically opposed to conversation, open-mindedness, and the expectation that opinions must be supported.

“Last semester a student in my first-year writing seminar liked to wear a “Make American Great Again” cap to class. I didn’t comment on it. He participated actively, listened closely to others, and enjoyed challenging others’ ideas as well as having his own ideas challenged. One of the hardest workers in the class, he was a gifted writer and achieved one of the highest grades. By the end of the semester, he was considering majoring in English, which I encouraged. I offered to be his advisor, but said he shouldn’t declare his major too soon. Part of the point of attending a small liberal arts college is trying a range of new courses and fields to discover areas of interest and talent you didn’t know you had. At the end of the semester, he told me how much he enjoyed our class and said he hoped to take more classes with me in the future.”

It’s notable that the list’s top seven slots are from the W&L English department. This is likely related to a statement my department issued in response to the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in August 2018. As the Washington Post reported:

A month after torch-bearing white supremacists marched at the University of Virginia, some members of the English department at Washington and Lee took their own stand. “This community has profited by slavery,” they wrote online. “We are complicit in its harms.”

The college, they wrote, “is named after two slaveholding generals with powerful legacies. . . . If it were ever right to celebrate the contributions of Robert E. Lee as an educator, that time is past. Lee’s primary association, to many Americans and across the world, is with white supremacy.”

That prompted heated backlash.

The three individuals who wrote and distributed “The ‘Dumbing Down’ of the Curriculum at W&L” call themselves the Generals’ Redoubt. According to their vision statement, they are “dedicated to the Restoration and Preservation of the History, Values and Traditions of Washington and Lee University and its Named Founders,” and their mission includes seeking to “prevent further retreat from the University’s history, values and traditions; protect revered campus buildings; and continue to honor the magnificent contributions of its Founders.”

Despite our differences in opinion, I had a pleasant exchange with one of them earlier this year:

Dear Mr. Wooldridge,

I’m not sure why I’m included in your mass email. Could you please explain? Also, it was unclear whether you had the permission of the two authors to forward their emails. Could you please indicate whether you did?

Regardless, I am pleased to see alums concerned about the future of W&L. I share that concern. Our school is in a moment of important transition, and it should be accomplished with the committed help of its extended community.

As far as the specifics of the first letter you forwarded, it’s a little odd to suggest the that hiring committee for the director of institutional history should cease their work after so many months of open effort. W&L makes a great many hires every year. The search for the director of the new learning and development center is happening right now too. By the premise presented in the letter, that search should also be halted–though why is not clear in either case.

Still, despite not presenting a clear line of logic, the core of the letter is expressing concern about the future of W&L and how it will present its history. That is an extremely valid concern. I’m glad you are taking it up with the president and, I assume, also with the board. That is your prerogative and perhaps even your duty as a person deeply invested in W&L. I applaud your commitment.

We may not always agree about future steps, but I hope your organization will express their opinions in a respectful manner while acknowledging that everyone involved, regardless of whether they seek change or continuation of the status quo, does so because W&L is so important to them.

If we all move forward with respect and openness then we move forward together and for the good of W&L.

I look forward to your response.

Sincerely,

Chris

He responded:

Professor Gavaler, I have been a part of an interested alumni group headed by Neely Young, Tom Rideout and myself for about 18 months. Yes I had permission from my cohorts to send the letter to the Washington and Lee community. If you read carefully the letter concerning Chavis, my signature was adjacent Neely Young’s. I did not have permission from President Dudley to forward his response to Tom Rideout but he must have understood that we would forward it to others. I felt an obligation to include his response to our request for purposes of clarification. I agree along with our alumni group that we need to move forward in a polite and open manner. I appreciate your comments.

Our group, The Generals’ Redoubt feel obliged to make an effort to communicate with all constituencies within the Washington and Lee community and share our point of view. We shall continue to communicate to the administration, the Board, and other members of the Washington and Lee community with their permission of course.

Thanks for your response and questions.

Rex Wooldridge, Class ’64

I then responded:

Dear Rex,

Thank you so much for your response. I assumed you had permission for the first letter, though I would feel more comfortable if you also had permission for the second. In the future, you might simply ask Will directly; as you implied, I don’t think he would object.

I also thank you for your polite and open manner. I think that will serve the W&L community well as we all move forward.

I would also like to suggest two principles that I think everyone involved should be able to agree on:

-

- Change for change’s sake is not desirable.

- Tradition for tradition’s sake is not desirable.

In short, what W&L does or does not do should be based on a careful and thorough evaluation of all options, with no prejudice for or against any one option in particular.

And so two more specific principles in regard to Robert E. Lee:

-

- Lee should not be vilified.

- Lee should not be glorified.

In short, Lee should be presented fully and so without bias in any direction. (I’m reminded of that old Dragnet catch phrase: “Just the facts, ma’am.”)

I sincerely believe that if W&L follows these principles, we will arrive somewhere that all constituents can embrace.

I hope you agree.

Thanks,

Chris

He did not respond.

Reading the most recent mass email and its attached documents, I am doubtful that he and his two retired friends are following the principles I suggested. They seem instead to be proceeding on biased impressions. The less significant ones include the assumptions that the analysis of pop cultural objects (including comic book characters) is frivolous, trivial, or otherwise inane, and that all graphic works are inferior to other significant works of art and literature. I do not feel the need to present counter arguments to either impression here–though I will happily do so if requested.

I am more concerned that these three individuals are making incorrect assumptions about the agenda of faculty members and about Robert E. Lee. Their stated third goal is to “Reverse the recent decision to shield the Recumbent Statue of Lee during University events, return the Peale portrait of Washington to Lee Chapel, and modify the renaming of Robinson Hall.” If these goals were the product of careful research and evaluation, they might be supportable. The authors, however, have not provided a well-reasoned, evidence-based argument for why these goals should be adopted. Though they wish the W&L curriculum to focus on “certain skills and intellectual competencies,” they do not display those skills and competencies themselves.

Given their interest in the Recumbent Statue of Lee and the Peale portrait of Washington, they would benefit from the visual analysis skills central to my comics-based courses. Advocating for “eliminating” a professor is a serious undertaking, but the depth of their displayed research begins and ends with a skimming of department course listings. They pose pointed rhetorical questions without having first sincerely asked and investigated why a course might productively focus on such things as race, gender, and sexuality. Their name (a redoubt is a defensive military fortification) communicates not the openness of inquiry that defines an educational institution such as W&L, but an a priori conclusion that undermines inquiry. By defining themselves as reflexive defenders of Robert E. Lee, they violate one of their own “Mission Themes,” to instill “a balanced and unbiased approach to teaching and learning.”

Finally, they claim to prioritize “opportunities for constructive dialogue,” and yet they did not respond to my last email. They also did not contact me to discuss the nature of my courses before distributing a document to thousands of W&L alums, students, faculty members, administrators, and trustees advocating that those courses and I be eliminated. They deleted me from their distribution list instead. I heard about the “Dumbing Down” list from two former Creating Comics students. I welcome constructive dialogue. I am a founding member of the Rockbridge Civil Discourse Society, a local group devoted to building bridges across the partisan divide through meaningful conversation. I would very much like to see such conversation taking place in the extended W&L community. I had hoped the Generals’ Redoubt would include meaningful participants. Instead they are modeling bias, shallow research, inadequate argumentation, and hypocritical rhetoric.

Still, I remain open. Should one of these individuals wish to engage in sincere conversation, my email address is listed on the English department webpage, just a click away from the course listings.

[The saga continues here.]

- 6 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

13/05/19 Comics at the new Shenandoah

I became Shenandoah‘s first comics editor last fall, and the second issue under new editor Beth Staples just went live. It’s as amazing as her first issue last November, and I’m thrilled and grateful to be a part of it.

The idea that the not-yet-reborn journal might include comics occurred to me a year ago while Leigh Ann Beavers and I were teaching our spring term course Creating Comics. Artist Miriam Libicki visited the art studio and showed us the opening chapters of her current graphic-novel-in-progress. As soon as Beth gave me a thumbs up in August, I asked Miriam if we could feature Glastnost Kids on Shenandoah. I also asked Maggie Shapiro, the person who brought Miriam to campus, to write an introduction. They both said yes.

Meanwhile, Beth added “Comics” to Shenandoah‘s Submittable portal, and submissions started flowing. The stand-out was by far Rainie Oet and Alice Blank’s “Wanting to Erase her Share of the Darkness.” I asked Beth if I could also interview them about their collaborative process, and she gave the thumbs up for that too.

Finally, I’ve also been serving as a fiction reader, and asked Beth if I could solicit one of my favorite authors, Stephen Graham Jones. Another thumbs up. The piece he sent though wasn’t the right fit–but for very complicated reasons. So I asked Beth if I could interview him about that, too. Amazingly, they both said yes.

So here are excerpts of all of the above:

1.

from “Animating Questions: An Introduction to Miriam Libicki’s Glastnost Kids“

by Maggie Shapiro Haskett

The experience of having one’s expectations violated can take a lot of directions, but I’ve only ever been delighted when, time and again, Libicki’s work surprises, confuses, and challenges me—while also offering unexpected moments of comfort and self-recognition. Starting in 2014, and just as much now, I am captivated by the parallel challenges she poses to both form and content in her work. Graphic novel as memoir? Sure, but as a format for scholarly interrogations or the presentation of rigorous academic research—that was something new and rare. When I found myself installed in the cozy director’s office at Washington and Lee University Hillel, the campus organization for Jewish Life, I was eager to introduce my students to Libicki’s beautiful boundary-busting work. As fate would have it, Chris Gavaler, W&L English professor and Shenandoah’s soon-to-be comics editor, was preparing to co-teach his Creating Comics course during my first spring in Virginia, and his enthusiasm for Libicki’s work was the final push I needed to bring her to campus.

“So what is a Jew?” Miriam Libicki’s narrator character asks in this excerpt from Glasnost Kids. “What is Jewish community?” I’d argue that those are two of the animating questions of the book as well as two of the questions that provoke and enliven Jewish communities everywhere, and especially on college campuses.

I’d also argue that Libicki’s work is at its most successful and provocative when we readers are forced to ask ourselves, “So what is a comic?” Libicki’s genre-bending work enlivens communities of readers, comics fans, and even scholars. For anyone with more than a glancing familiarity with the world of comics, it is a given that the genre is diverse and expansive. Libicki, though, dwells and works within formal questions that echo the identity questions articulated in Glasnost Kids. Can an academic paper include the use of the first person? What about the author’s personal experiences and connections to the subject? How about visual depictions of the author, cleavage and all? And comics? Can they really be explicitly about contemporary sociological questions? Are they a vehicle for sharing rigorous scholarly research? Given the depth and integrity of Libicki’s research and her mastery of both narrative and graphic, the answer can only be a resounding yes, and thank goodness. We need her stories, but most of all we need her questions and her provocations.

[Read all of Maggie’s Introduction here, and the opening pages of Miriam’s Glastnost Kids here.]

2.

from “Unveiling her Glorious Share: An Interview with Rainie Oet and Alice Blank”

Chris: So you’ve referred to “poems,” “sections,” “narrative,” and “the book.” It’s interesting how those are synonyms and how they’re not. I would probably call “Wanting to Erase Her Share of the Darkness” a poetry comic, a term I find to be a wonderfully and intentionally under-defined category that encompasses a range of image–text sequences, including formally traditional comics with gridded panels and word containers, but that explore untraditional content in untraditional ways. Do you have a preferred category for you work—comic, poetry comic, sequential art, etc.—and to what degree do you consciously engage with traditions and genres as you collaborate?

Rainie: It’s a funny bunch of classifications. Poetry comic and graphic narrative are interchangeable to me for this work because I see the writing as simultaneously poetry and fiction. The book, Glorious Veils of Diane, as a whole, is a novel-in-verse or a book of poems. The in-progress illustrated counterpart is a graphic novel or a graphic poetry book. The way I think of the project as a whole is like my favorite card from Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies: “What are the sections sections of? (Imagine a caterpillar moving).” “Wanting to Erase Her Share of the Darkness” is one such section. In both my noncollaborative writing and my collaborative work, I try consciously to disengage traditions and genres. It’s an interesting and tricky thing, the idea of unlearning, of being free from. I think the best way to do this is to become as aware as possible of the traditions and genres that we absorb just by being in the world, and then to try to hold that awareness while writing. When I do that I feel like I’m able to bring new ideas to a project.

Alice: I could definitely see talking about this work as a “poetry” comic, but I traditionally just describe my work as comics. I worry about differentiating distinct kinds of writing as different kinds of comics—there are plenty of abstract narratives that I think would blur the line between poetry and prose (and indeed the poem from which this is derived is an example), and I wonder at the sort of comics that get left behind when labels like “poetry” are added to the name. American comics are still burdened with the image crisis brought on by the Comics Code Authority. Bringing in the poetry label might differentiate this work from a colloquially understood superhero punch-fest, but I want to abstain from adopting terms that suggest my work is in any way separate from or superior to those forbearers. I want to play a part in the ongoing cultural project to elevate “comics” as a label past its Marvel-or-DC connotations, so I try to eschew words that shift my work away from the base term.

[Read the rest of the Interview here, and Rainie and Alice’s “Wanting to Erase her Share of the Darkness” here.]

3.

Gutting the Chicken: A Conversation with Stephen Graham Jones

Stephen Graham Jones submitted “Chicken” to Shenandoah last October after we solicited him. We rejected it—for complicated reasons. Like any horror story should be, it was uncomfortable to read. But did it go too far? Where does fictional uncomfortable become real-world offensive? That dividing line may be hazy, but a literary magazine doesn’t have the luxury of ambiguity: either you publish a story or you don’t. And we decided not to.

Rejections are a necessarily massive, behind-the-scenes part of any magazine, and usually after a nice, thanks-but-no-thanks note to a contributor (an especially difficult proposition after a solicitation), the scene ends. But this time we thought: It’s such a powerful piece, hard to forget. Wouldn’t it be interesting to talk to Stephen about our reasons for saying no to “Chicken” and hear his thoughts about writing it? Though that is pretty much the opposite premise for an author interview, we reached out to Stephen anyway and were delighted when he was game. Afterward we realized for readers to make sense of any of this, they would need to be able to read the story themselves. So we are publishing “Chicken” after all, only now in the context of this broader, why-we-rejected-it-before-we-didn’t conversation.

[Read Stephen’s story and the interview here.]

Tags: Alice Blank, Miriam Libicki, Rainie Oet, Stephen Graham Jones

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

06/05/19 My Process on a Work-in-Progress

1. Begin with a plate from my favorite 19th-century photo-comics collection, Eadweard Muybridge’s 1887 motion studies Animal Locomotion:

2. Select six sequenced angles and arrange them in a 3×2 grid:

3. Draw the figures in panel one:

4. Draw the figures in panel two:

5. Combine panels one and two: 6. Add water and sand transparencies:

6. Add water and sand transparencies:  7. To be continued …

7. To be continued …

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized