Monthly Archives: May 2021

31/05/21 Cartooning In and Out of Your Twenties

“Cartoon” can mean a lot of things. As a drawing style, those things usually include simplification. A cartoonist takes a massively detailed real-world subject and extracts the most defining elements and reproduces them through a few well-placed lines. The cartoonist also probably alters those lines, distorting them by selectively expanding and shrinking to create shapes that evoke but don’t match the original content. How simplified and how distorted offer wide spectrums, and every artist’s personal style is its own idiosyncratic cross-point on that simplify-distort grid.

Look at Sophie Yanow and Lisa Hanawalt. Both are renowned cartoonists, each with recent graphic novels (Yanow’s The Corrections and Hanawalt’s I Want You) released a month apart by their publisher Drawn & Quarterly last fall, but their styles occupy very distant locations in what they show to be the vast world of cartooning.

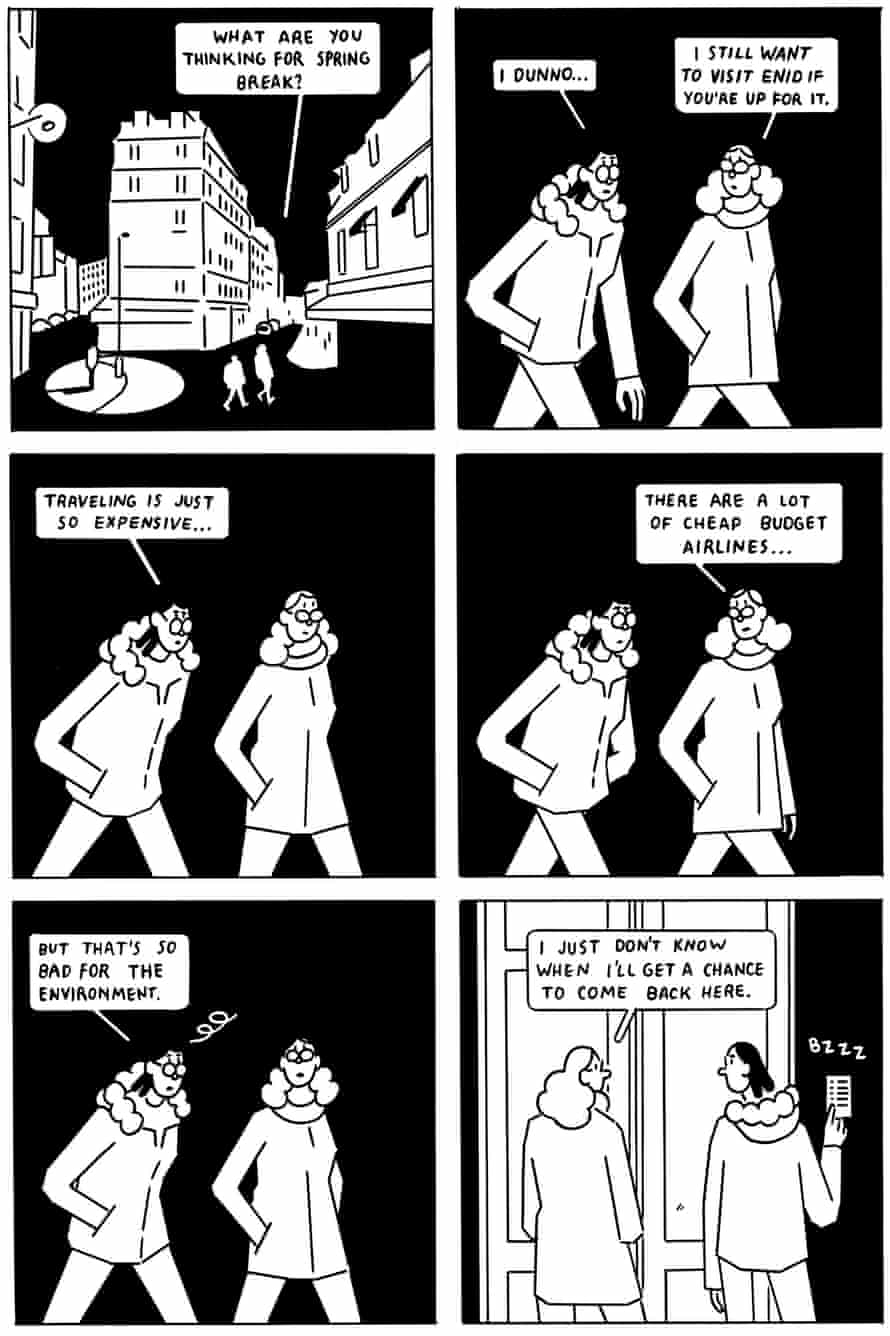

Yanow is a minimalist. Her protagonist—a younger version of herself in college—consists of a small repeating set of identical marks. Her eyes are the circles of her glasses perched on the tinier circle of her nose. Her mouth—sometimes a straight line identical to the straight lines that represent the stems of her glasses, sometimes a slightly curving smile or frown, and sometimes just a perplexed dot—does all of the work of expressing her limited emotions. Her body is even more geometric, elbows and knees often at right angles or undifferentiated in the straight lines of her straight limbs. The proportions are pleasantly odd too, her head a little too small, her torso a little too big, though not so exaggerated that she departs from a feeling of improbable naturalism.

The rest of Yanow’s world obeys the same simplified laws of reality. Some settings are evoked by even fewer lines, each the same unaltering thickness as the frame lines surrounding them. Yanow doesn’t draw a single crosshatch in her entire 200-page memoir. Either a shape is opaque black or empty white. Her layouts are equally consistent: six squares arranged in three rows of two. The few variations (white spaces replace panels during the final train ride home and when Yanow is finally alone and decompressing) are some of the most evocative moments in the memoir.

Hanawalt is a maximalist. Her protagonists—many of whom have animal heads but human bodies—consist of intricate patterns of fur and clothing, offset by comparatively sparse but equally intricate shapes that define their surroundings. Her crosshatching is often meticulous, giving realistic depth and texture to the characters’ exposed heads and limbs and so intensifying the surreal effect. When Hanawalt leaves the interior of shapes unshaded, the pages resemble absurdist coloring books wonderfully inappropriate for humans of any age.

Where Yanow champions blocky consistency, Hanawalt wanders through multiple layout variations. Some pages are single images, some are partitioned into single-line frames, other into gutters, and still others are entirely open-framed. Her rendering style roams just as freely, from thin-lined black to gray washes to opaque grays. While most of her lines are sharply precise, a few pages feature thicker looser art, as if an uncredited guest artist dropped by. Most are clearly Hanawalt-esque, though unexpected undertones of Shel Silverstein and Phoebe Gloeckner stroll through too.

Hanawalt’s free-roaming styles are well-suited to her collection, which (as her bird-headed cartoon self explains in the introduction) compiles her pre-animation (BoJack Horseman, Tuca & Bert) minicomics from 2009 and earlier. Though some characters recur (She-Moose and He-Horse get top billing), most are an anonymous cast of oddball humans and half-humans muddling through early 21st century existence. Though Hanawalt’s humor makes things a little more surreal (list of invented dances, instructions for pretending to jack-off while driving, things you can do nightmarishly wrong in grocery stores), but the baseline reality is uncomfortably familiar.

Though Yanow’s reality is explicitly real—The Contradictions documents a European hitchhiking trip she took while studying abroad—its unrelenting layout and style norms suggest the confused rigidity of her younger self as she struggles to navigate a paradoxically unpredictable world. Where Hanawalt is inventing a hybrid world in order to reflect on ours, Yanow’s younger self seems trapped in her own 3×2 gridded mindset which inaccurately partitions her experiences. She is a quietly unreliable visual narrator, unaware that her mismatched traveling companion and their awkward inability to relate is the source of her gently tragic disconnection.

Both cartoonists are drawing self-portraits, Hanawalt indirectly, Yanow explicitly. Their bodies and so their sexualities are part of their imagery. Yanow’s twenty-year-old self is openly gay, but she does not seem especially at ease with that fact—or possibly with any facts about herself. Though there is no overt sexual tension between her and her kleptomaniac anarchist friend Zena, the rules of plotting imply it, even as Yanow’s rules of representation stifle the possibility through a kind of visual asexuality. The characters seem lost inside the flat geometry of their clothes and bodies. The genre is coming-of-age, which Yanow quietly thwarts by allowing her cartoon self so little room for growth.

Hanawalt, however, is overt in her twenty-something sexuality. Where Yanow seems incapable of recognizing let alone expressing physical desire, Hanawalt’s title declares it as organizing principle. There are a few explicit sex acts (penis hula hoop, sexy real estate brokers, children’s dinosaur porn), but the grainy texture of animal fur surrounded by delicately patterned clothes implies what otherwise goes undrawn. Hanawalt’s half-humans are animals all the way down. We all are. Though she sometimes channels the sexual exuberance of Julie Doucet or Fiona Smyth, Hanawalt’s surreal bodies are also horror-tinged, often vomiting inexplicable clumps of noodles or baby chicks. The most disturbingly powerful sequence is She-Mouse’s visit to a surreal abortion clinic.

Despite their considerable differences in genre, style, and character temperament, Yanow and Hanawalt explore the same inexplicable underworld of longing, Yanow from the terrifying entry point of her twenties, and Hanawalt from the ravaged exit point of hers. Wanting and contradiction abound in both.

Tags: I Want You, Lisa Hanawalt, Sophie Yanow, The Contradictions

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

25/05/21 Comics from Creating Comics

I now have statistical evidence to support the claim: “Third time’s the charm.”

The Spring 2021 iteration of Leigh Ann Beavers and my Creating Comics course has produced the strongest batch of student comics yet–and that was already an impressively high bar. I would like to take a little of the credit, but it really comes down to the talent in the room. Look for yourself. Our library featured a row of poster-sized pages for the Spring term festival:

And here’s a closer look at some individual pages:

Arden Floyd:

Audrey Dietz:

Everett Heebe:

Gabriela Gomez-Misserian:

Grace Williams:

Jessy Xu:

Katie Cones:

Lauren Newton:

Maddie Brazil:

Mitchell Roberts:

Naila Rahman:

Nayongi Borthwick:

It was also the first time Leigh Ann and I used our own textbook–which was odd for me, but apparently pretty effective. Of course now we want to scramble the whole syllabus and reinvent a new comics wheel, mainly just for the fun of it. I can’t wait to see what our Spring 2023 students create.

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

17/05/21 Abstract Comics

These are one-page, abstract comics from the students of ARTS-ENGL 215, a hybrid creative-writing/studio-arts course called “Making Comics” that I’m co-teaching again this spring term with my co-author Leigh Ann Beavers.

Nayongi Borthwick:

Naila Rahman:

Mitchell Roberts:

Maddie Brazil:

Lauren Newton:

Katie Cones:

Jessy Xu:

Gabriela Gomez-Misserian:

Everett Heebe:

Arden Floyd:

Grace Williams:

Audrey Dietz:

Leigh Ann and I discuss abstract comics briefly in our textbook Creating Comics, which was published in January. If we ever get to make a second edition, we have so many new student illustrations to highlight!

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

10/05/21 Appropriation/Transformation Comic #1: Picasso, Woman in a Hat, 1935/2021

After spending last month discussing the ambiguous boundaries of appropriation art and what may or may not count as fair use (parts one, two, three, and four), this week is the first in a series of experiments appropriating a work of art and transforming it into a comics sequence. I assume the final image would not violate copyright law, but I’m uncertain about any of the middle ones. More importantly, is Picasso’s untouched original transformed simply by the change in context? Sadly, the only way to find out is to be sued by Picasso’s heirs.

[Update: SCOTUS ruled on May 18, 2023, which I discuss here.]

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

03/05/21 Princes of Plagiarism: Drawing the line for comics copyright infringement (part 4 of 3)

[Update: SCOTUS ruled on May 18, 2023, which I discuss here.]

Is this copyright infringement?

The image on the left is the February 2002 cover of Sports Illustrated featuring a photograph of model Yamila Diaz-Rahi taken by Jeff Bark. The image on the right is the May 2003 cover of Sojourn No. 22 drawn by Greg Land. The second image is presumably derived from the first, probably by tracing the first with a stylus to transfer the tracing to a computer program digitally.

I’m not sure what the statutes of limitations on copyright law are, but the Sojourn publisher, CrossGen, went out of business in 2004, perhaps leaving no one to sue if Greg Land produced the image made-for-hire, meaning CrossGen purchased the copyright. Since Jeff Bark was employed by Sports Illustrated who presumably purchased his work outright too, he may or may not have grounds to sue. The image is of Yamila Diaz-Rahi, so she presumably would have grounds, and since CrossGen doesn’t exist, perhaps she could sue Greg Land directly.

Of all of those potential legal battles, I’m not aware of any actually occurring. No one sued anyone. Why not? Even if CrossGen were still in business and Diaz-Rahi, Bark, and Sports Illustrated were aware of the potential infringement immediately after the publication of Sojourn No. 22, I still suspect no one would take any legal action because Land’s use of the Bark photograph would be protected by fair use.

Even though the new image was created as part of a commercial product (and so not exempt due to purpose), “the amount and substantiality of the portion used” probably does not exceed the vague limits suggested by previous court rulings (which I’ve been describing obsessively for the past three posts).

At what I previously described as the micro-level, the second image uses none of the raw materials of the first image directly (which makes it dissimilar to Warhol’s Prince and Fairey’s HOPE). But at the macro-level, the gestalt effect of the new image clearly replicates the source. To paraphrase the Second Circuit Court of Appeals: “the degree to which Bark’s work remains recognizable within Land’s, there can be no reasonable debate that the works are substantially similar.”

And yet, I’m guessing, not similar enough, since it triggered no lawsuits. And neither has Land’s other equally derivative artwork:

And Land is hardly alone. The practice of comics “swipes” originates long before digital tracing made it even easier. Fred Guardineer copied N.C. Wyeth’s 1919 The Last of the Mohicans illustration for Action Comics No. 8 (January 1939).

And Batman co-creator Bob Kane was a notorious swiper, usually of other comics artists.

Comics artists also swipe from themselves. Neal Adams reproduced his cover for Superman No. 243 (October 1971) for his cover of Jonah Hex No. 91 (June 1985).

Since DC published both, copyright infringement wasn’t possible. But what about when an artist swipes his own work after moving from one company to another, as John Byrne did between Marvel and DC?

This is distinct from “homages” where the point is to evoke the original:

Including across publishers:

So why are comics seemingly exempt from U.S. copyright law? The short answer is they’re not. But the law requires lawsuits, and if no one alleges infringement, the law is moot. So the more relevant question may instead be: why is it so rare to sue a comics publisher for copyright infringement?

Returning to the first example, I think sometimes it has to do with the degree of transformation. In addition to variously altering the physical content of Bark’s photo, Land uses an image of a real person in order to depict a fictional person. I’ve never read Sojourn, but here’s a synopsis of No. 22:

“The quest continues as Arwyn ventures deep into the desert wastes of Oudubai, but her deadliest enemy may not be the sand, the heat or the troll pursuers dogging her every step. The greatest danger may well come from one of her own companions – a thief who has designs on the very Fragments Arwyn carries.”

I’m guessing, based on the faux mid-eastern veils that Land drapes on Diaz-Rahi, that the image is of the “thief” from “Oudubai” (I’m not going to plunge into an Orientialist critique right now, so I’ll just say that Land’s use of porn for his superheroine swipes may not be his greatest shortcoming). That’s very different from the infringement case that started this now four-part sequence of posts, where Warhol used an image of Prince to create an image of Prince:

That seems to be a self-evidently bad idea, since a primary point of appropriation art is its transformative quality.

According to New York Times art critic Blake Gopnik, the ruling against Warhol “had the effect of declaring that the landmark inventions of Duchamp and Warhol — the ‘appropriation’ they practiced, to use the term of art — were not worthy of the legal protection that other creativity is given under copyright law.”

While the ruling concerns me too, Gopnik performs a rhetorical sleight-of-hand by implying that Warhol’s Prince and Duchamp’s Fountain are essentially alike. They’re not. Duchamp took a urinal, turned it on its side, signed it, titled it, and placed it in an art exhibition, thus transforming it through a change in context that altered the nature of the object itself.

A urinal became a sculpture.

The equivalent for Warhol’s Prince would be if Warhol took a urinal and transformed it into a somewhat different urinal.

Which now makes me rethink my own self-portrait. If my photograph (okay, it’s a Zoom selfie) had been used by another artist without my permission, would I have the basis for a successful lawsuit?

The fact that I still don’t know the answer to that question is evidence that U.S. copyright law is in need of some serious clarification.

[This somehow evolved into a four-part analysis (one, two, three, four), with an on-going artistic coda starting here.]

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized