Monthly Archives: February 2021

22/02/21 The Future Is Still Laughing

I’d thought I was only making the above solo image, but looking back at my saved files, I discovered this sequence. Though it documents an evolving work-in-progress as I experimented with extracted pixels, it feels like the hair is somehow growing and exploding in the world of a story too. Since I feel a robotic connotation in the squares forming the body, and a less-easy-to-define distortion of the face, such a world of fantastical transformation feels possible too. My use of MS Paint grounds the image-making in an obsolete past, or maybe a parallel retro-past timeline. Either way, the laughter is optimistic–and so a future working its way here right now.

These are photo illustrations. I don’t remember what town we were in, only that it was a family brunch in some lovely and possibly vegan dinner somewhere urban, DC maybe? The first thing I did was remove myself. The last step was ordering a physical print on canvas mounted on a wood frame. I was planning to submit it to a couple of galleries in Charlottesville and Richmond. That was about a year ago, just minutes before the pandemic and lockdown. An impossibly long sci-fi year. Glad the future is still smiling.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

15/02/21 The Paradoxical Self-confidence of Self-deprecation vs. Racist Microaggressions

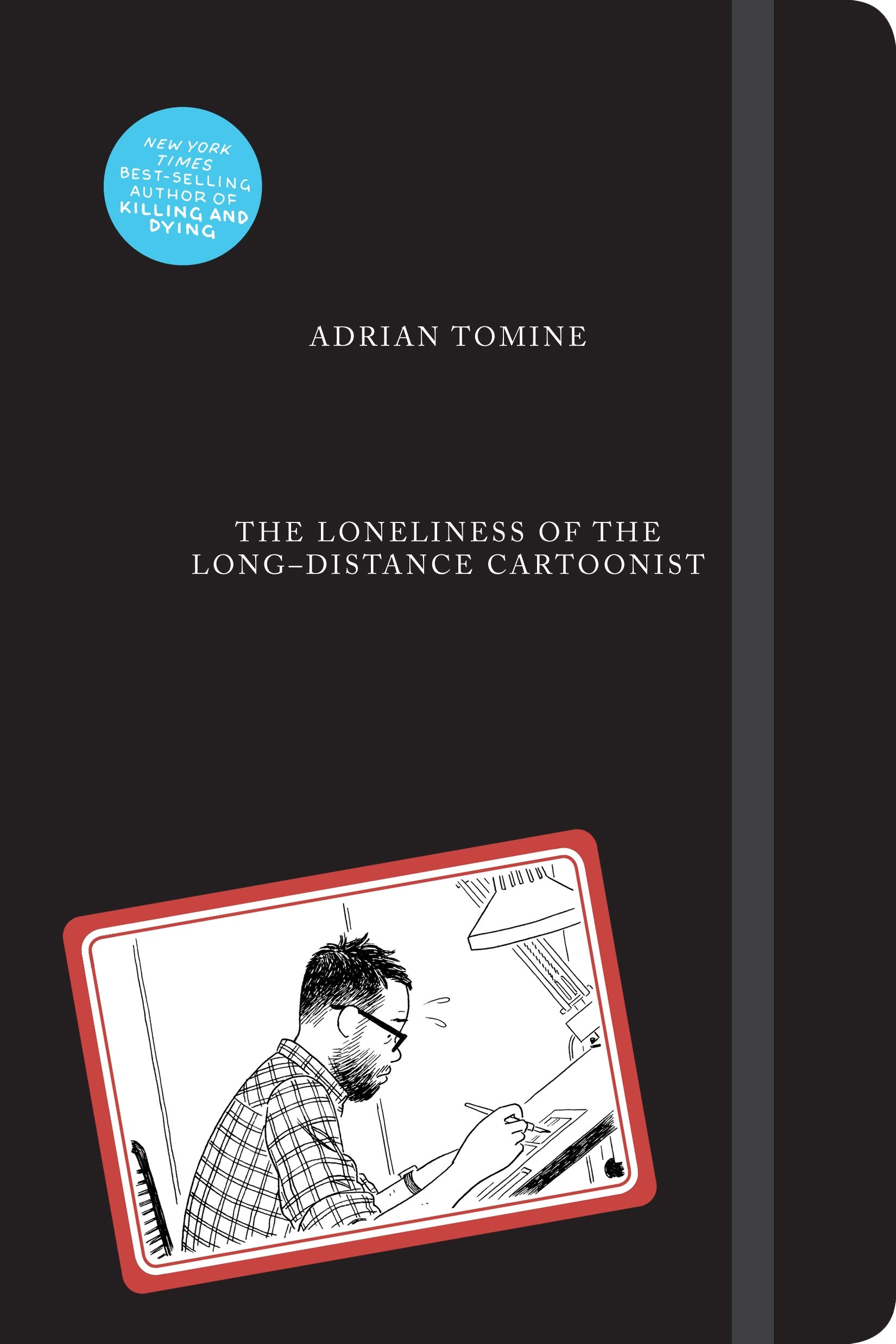

It’s hard to name a more highly regarded comics artist than Adrian Tomine. Though none of his books crack the top tier for either best or most famous graphic novels (Maus, Persepolis, Fun Home, Watchmen), his continuing stature and consistently excellent output is hard to rival. Not that you would guess that reading his memoir about his career in comics. While some of his previous work suggests a clear autobiographical edge (his novel Shortcomings offers a cringingly sharp focus on the experiences of Japanese Americans), Tomine has been content with the protective aloofness of fiction. Until now.

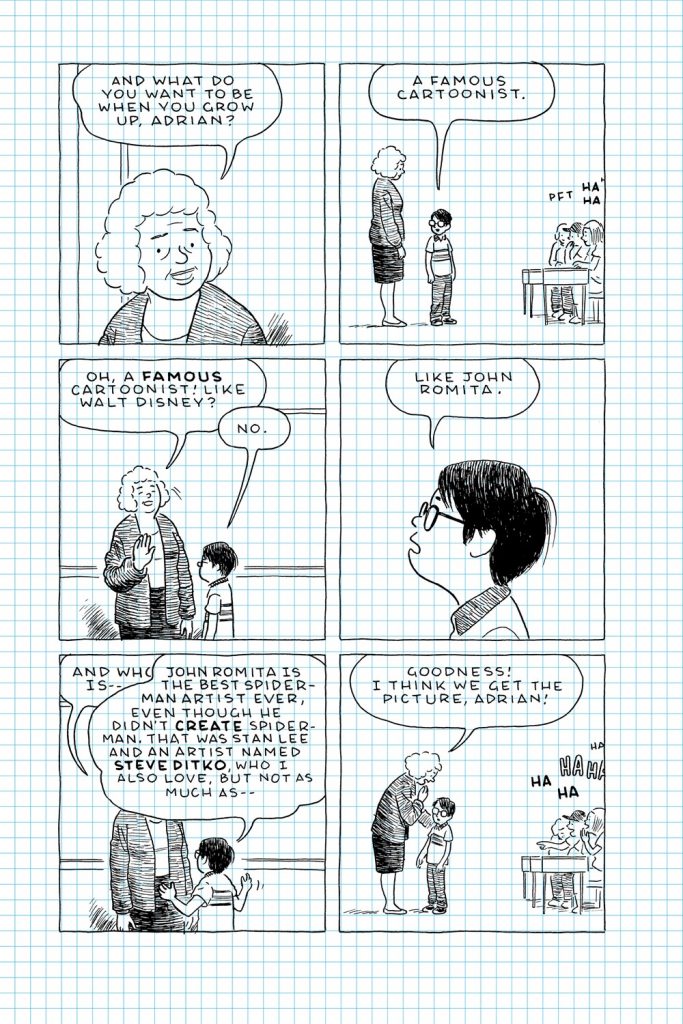

Shifting the spotlight to himself comes with a shift in tone. The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist does not feature Tomine’s signature understatement. Instead, it’s a comic in that other sense: he’s trying (and succeeding) to be funny. Every page is a 3×2 grid, often with the narrative rhythm of a stand-alone comic strip, including a punchline in the concluding square. The four pre-title opening pages establish the norm with the book’s only glimpses of his childhood: a quickly paced sequence of humiliations, including bullies, well-intentioned mishaps by would-be allies, and Tomine’s relentless self-sabotage. I suspect most readers will be able to relate.

What’s surprising though is how that childhood motif doesn’t change with adulthood but instead defines the tone of the whole memoir. More than a decade passes in the narrative leap from middle school to his first comic-con, but it’s as if Tomine is still trapped in that same purgatorial lunchroom. His continuing career features the same kinds of social cliques, insults, bullying, and brutally disinterested bystanders.

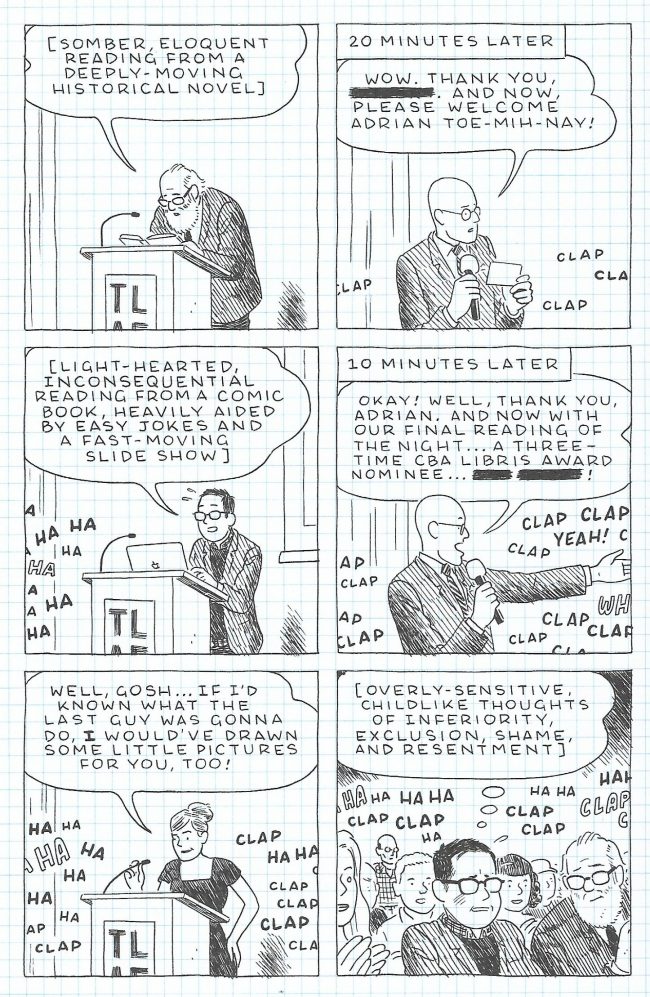

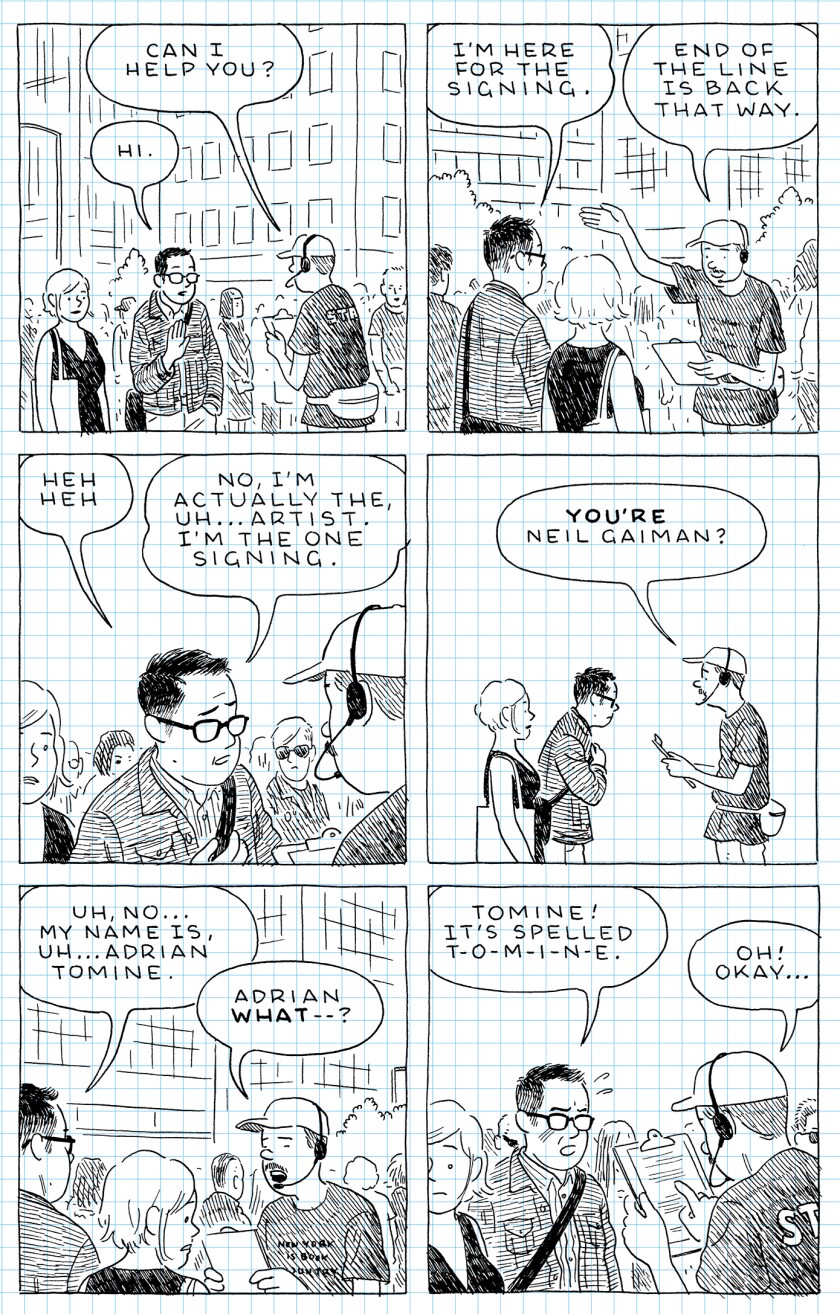

The list is impressive: Tomine writhes over a bad review. He’s mistaken for an internet service guy by a famous cartoonist. He sits through desolate book signings (once with the added humiliation of fake customers phoned in by the store owner in a failed attempt to lessen the humiliation). He’s heckled at a reading. He’s insulted by a fellow panelist. He’s upstaged by Neil Gaiman. He’s upstaged by Chloe Kardashian (plus no one laughs at his Thomas Pynchon joke). He’s mistaken for Daniel Clowes. His stalker calls him overrated. He’s spotted eating alone in a fast food place by pitying fans.

That’s not even the complete list, because the memoir is a sequence of Tomine’s worst comics experiences. There’s something perversely entertaining for a memoir about the career of its extremely successful author to stay so relentlessly focused on failures. It turns The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist into a kind of anti-memoir, an extended comic strip gag. Tomine waits till the last scene to acknowledge the joke: “My clearest memories related to comics—about being a cartoonist—are the embarrassing gaffes, the small humiliations, the perceived insults … everything else is either hazy or forgotten.” And his memoir proves it.

But it also quietly undermines that self-deprecation. When he includes an eight-page story about an embarrassing bowel movement, the comics connection is tangential—revealing that the selection is absurdly stacked against him. Clues of his exceptional successes also shine through the crack of his comically negative faulty narration. Sure, he ends his radio interview with exactly the sort of clumsy “Thank you!” that he was desperate to avoid—but the interview was on Fresh Air. Yes, he made a lame expression when he looked back at the camera recording him—but only because he was famous enough to attract the attention of a French TV news show while being honored at a festival. No one in the audience laughed at his joke, but he was being interviewed on stage about his success as a New Yorker cartoonist.

The intentionally myopic memoir leaps over massive and presumably positive swaths of his non-comics-related life. When his daughter makes her first appearance, she’s already speaking in full sentences. His future wife is more integrated, but only because she’s there to experience some of his humiliations beside him. At first, that means witnessing another desolate book signing (and now I’m wondering if the repeated comparisons about line lengths is a veiled penis joke), but soon she moves from spectator to dedicated participant, ready to shout down a rude stranger at the next restaurant table haranguing his date for liking a Tomine book. Tomine’s sixth-panel thought-bubble punchline is revealing: “I’m gonna ask her to marry me.”

The memoir has a subtle subtext too. Though most of the litany of humiliations might resonate with any reader, some are specifically racist microaggressions—as when a famous author (most names are blacked out as if by a censor’s pen) gratuitously asks Tomine’s nationally and then declares: “I love Jujitsu.” When Frank Miller (one of the most famous writers and artists in superhero comics) reads the nomination list at the Eisner Award banquet (the comics equivalent of the Oscars), he says: “Adrian … uh … I’m not even going to try to pronounce that one!” It becomes one of the memoir’s running gags—“Toe-mine,” “Toe-meen,” “Toe-mih-nay”—not because it’s funny, but because it’s presumably a running discomfort of his actual life.

Happily, even Tomine’s artificially negative premise buckles under the weight of his actual happiness. He appears to be in a deeply loving marriage (even if his wife dozes off as he rants). He appears to have a deeply loving relationship with his daughter (even if her teacher apologizes to all the parents that he drew poop during his class presentation on being a cartoonist). His outward attitude seems to shift too, when, even though he feels insulted to be charged for a “gift” pizza, he’s nice to the chef as he leaves the restaurant with his family.

Apparently thinking you’re having a heart attack has its psychological benefits. His death flashes in his mind (in a sequence of the memoir’s only unframed panels), and as he waits in a hospital bed for his test results, he composes a moving letter to his family (in the memoir’s only full-page panel). Those breaks in form signal a deeper break in his self-deprecating ways, even though the memoir’s final paradoxical punchline is his decision to write a memoir about those humiliations.

Maybe that’s the real joke: self-deprecation can mask deep confidence. If so, Adrian Tomine (Tom-ine-y? Toom-in-ah?) is the most confident comics artist in the world.

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

08/02/21 Editing a Comics Anthology

I was going to include “Feminist” and/or “Inclusive” in the title of this post, or, more cutely, “Feminist” and/or “Inclusive,” meaning that any anthology should be both, making the adjectives redundant. But having now edited an actual anthology, I know I’m not the person who gets to evaluate the success of those aspirations. I also thought about beginning the title with “How to Edit,” but again, now knowing the challenges of the task, I feel less certain about offering advice than just reporting my efforts.

Bloomsbury published Creating Comics: A Writer’s and Artist’s Guide and Anthology at the end of January 2021. When I accepted the assignment of writing the textbook, the last word in the title seemed like an afterthought—one I could maybe avoid since the other textbooks in the creative writing series were words-only (Short-Form, Nature Writing, Poetry) and reproducing multi-page comics is a very different (and expensive) animal. Fortunately, my editor said no, I really did have to include an anthology. So I wrote in the proposal: “Based on permissions and availability, selections will be made from the following master list.”

Brainstorming that dream list was easy enough—though narrowing to black and white art didn’t narrow the field as much as I’d expected. The first version included sixty titles. If you add them up (which I just did again) you’ll find 35 men. Which means I flunked my first test: at least half of the authors need to be woman-identified or nonbinary. That’s a pretty minimal requirement, and I think I blew it because I wanted to include several early artists in a field that was so male-dominated for decades. The second half of the list includes more women, but that’s not by chance. Instead of traveling to research libraries, I used my university leave fund to expand my personal library, prioritizing works by women to offset the industry’s gender imbalance. I continued that practice when selecting new releases to review at PopMatters.com (I averaged about two reviews a month for close to three years). As a result, whenever I am writing an article or chapter, the odds of my choosing an example by a female artist increase significantly based on how many are literally in arm’s reach of my desk.

There are other oddities about that original list. Picasso? I wanted his Bull series—part of my hope of showing that comics (or at least sequenced images) are already widespread in fine arts. I wanted two paintings from Glenn Ligon’s 1989 series How It Feels to be Colored Me for the same reason—while also demonstrating the hybrid nature of words as images. There are other non-comics comics artists in there too, but once I moved from thought experiment to the tasks of actually editing (researching copyrights, contacting owners, negotiating prices, issuing contracts, acquiring usable scans, keeping within my publisher’s budget, etc.), many of my thought bubbles burst.

Though photographer Elizabeth Bick rode to my fine-arts rescue, I was surprised by the number of traditional comics publishers who do not answer permissions queries. Some do respond, but only after you make many attempts, a process that includes researching company websites for employees with likely-sounding job titles to leave messages. I got to know more than one phone receptionist by first name.

I decided early on to forego Marvel and DC. I’d had mixed results with them both when requesting image rights for illustrations in my previous books. I might have cut them anyway, since they hardly need additional attention—though I was sad when I realized that meant no Howard Cruse (Stuck Rubber Baby made my second list). I cut Frank Miller’s Sin City even before it became clear that no amount of effort would ever compel anyone working at Dark Horse to return my messages. Ditto for First Second (there’s an adaption of a Thomas Hardy poem from a Word War I poetry comics anthology I still long to have). The creators of the photo-comics poetry website The Softer World stopped making new strips a couple years ago, but I still thought they would have responded (I even tried Twitter that time).

My biggest disappointment was Kyle Baker (my second list was significantly better than my first list). I did manage eventually to correspond with an artist named Kyle Baker, but he informed that, alas, he was not that Kyle Baker (though his website is sincerely impressive). I also discovered that Baker’s company name, Quality Jollity, is now owned by a sex toy website (I keep typing and then deleting a follow-up detail about that).

Also, it turns out Random House owns half the planet. I spent a lot of time at their “permissions portal,” discovering just how many imprints redirect there (Pantheon, Penguin, Schocken). They do not, however, continue to hold the rights for The Best of American Splendor and could offer no help tracking down Harvey Pekar. NBM informed me both that they no longer held the rights for Veronique Tanaka’s Metronome, and that there’s no such person as Veronique Tanaka. One Google search later and I learned that Bryan Talbot had taken the name of a Japanese woman as a pseudonym (I decided I didn’t need Metronome after all). Princeton University Press uses Copyright.com, which is a nightmare website if you’re trying to forward password-protected contract links to your London editor from rural Virginia.

There are so many more: IDW, Penn State, New York Review, Koyama, Fantagraphics, Drawn & Quarterly—those last three I leaned on most heavily, in part because I’d fallen for them while writing all those reviews, but also because they all (eventually) responded to my queries and so filled the gaps when others didn’t.

Of my original list of sixty works, seventeen made it into the eventual anthology. That’s a good thing, because the final table of contents is significantly better than my first I-really-don’t-want-to-have-to-do-this-anyway list. It’s still far far from perfect, but I will await others’ opinions about whether it is also “Feminist” and/or “Inclusive” in terms of race, ethnicity, sexuality, and other angles of differences. My failings are at least hard-earned.

The Anthology includes:

Jessica Abel, from La Perdida

Yvan Alagabé, “Postscriptum”

Lynda Barry, “Ernie Pook’s Vague Childhood Memories”

Alison Bechdel, from The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For

Elizabeth Bick, “Street Ballet IV, New York, NY” and “Street Ballet XIII, Houston, TX”

Michael Comeau, from Winter Cosmos

Leela Corman, from Unterzakhn

Marcelo D’Salete, from Angola Janga

Eleanor Davis, “Darling, I’ve Realized I Don’t Love You”

Aminder Dhaliwal, from Woman World

Marguierite Dabaie, “Naji al-Ali”

Max Ernst, “First Visible Poem” (1934)

Inés Estrada, from Alienation

Liana Finck, from Passing for Human

Renée French, from micrographica

GG, from I’m Not Here

John Hankiewicz, “Lot C (Some Time Later)”

Jamie Hernandez, “How to Kill a … by Isabel Ruebens”

William Hogarth, Gin Lane and Beer Street (1751)

Gareth A. Hopkins and Erik Blagsvedt, from Found Forest Floor

R. Kikuo Johnson, from Night Fisher

Miriam Katin, from We Are On Our Own

John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell, from March: Book 2

Miriam Libicki, from Jobnik!

Sarah Lightman, from The Book of Sarah

Daishu Ma, from Leaf

José Muñoz and Carlos Sampayo, from Alack Sinner

Sylvia Nickerson, from Creation

Thomas Ott, “The Hook”

Kristen Radtke, from Imagine Wanting Only This

Keiler Roberts, from Chlorine Gardens

Gina Siciliano, from I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi

Fiona Smyth, from Somnambulance

Marjane Satrapi, from Persepolis

Jillian Tamaki, from SuperMutant Magic Academy

Craig Thompson, from Blankets

Seth Tobocman, “The Paranoid Truth”

Adrian Tomine, “Drop” and “Unfaded”

C. C. Tsai and Zhuangi, from The Way of Nature

Felix Vallotton, Intimités (1898)

[If you’re interested in buying a copy, the Bloomsbury site offers slightly lower prices (including a PDF) than at Amazon (though Amazon is worth a glance for the preview of the first 33 pages). If you’re thinking you might want to teach from it, the Bloomsbury site also lets you “Request exam/desk copy.” Also, if you are interested in writing a book review, contact: AcademicReviewUS@Bloomsbury.com (if you’re in North America) or AcademicReviews@Bloomsbury.com (if you’re anywhere else on the planet) to request a review copy.]

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

01/02/21 Creating Comics: A Writer’s and Artist’s Guide and Anthology

The first thing I did when Bloomsbury asked me to write a textbook about making comics was to ask Leigh Ann Beavers to be the co-author. I had gone to her a couple of years earlier when I was searching for a professor at my university to co-teach a hybrid creative-writing/studio-arts course on comics. Co-teaching, like co-writing, is a weird business that’s mostly about the hard-to-quantify intangibles of personal interaction. I can’t remember who suggested I talk to Leigh Ann, but after one meandering chat in her oddly non-rectangular office, she was on board.

We taught Making Comics for the first time in spring 2017. It was a massive success, and so when we taught it again in 2019, we decided to change everything. When we teach it for a third time in spring 2021, we’ll have to change it yet again—though our next roster of students will have copies of Creating Comics for guidance.

A lot happened between the 2017 and 2019 classes, and those changes shaped the book. I originally approached the creative process the way creators at Marvel and DC tend to: a writer writes a script, and then an artist draws the script. I also teach fiction writing and playwriting, so I focused the first half of the term on script-writing, and Leigh Ann focused the second half on transforming those scripts into actual comics. But that process was born from a business model that employs separate writers and artists, each engaged in multiple projects, each on its own conveyor-belt of a production schedule.

Why begin with a script? Because editors can read them. It gives them an idea of what a later comic could be, plus there’s something tangible to critique and revise. Editors, like writers, think in words. But comics aren’t primarily about words. They’re foremost a visual art. What visual artist begins by writing a description of what she plans to draw? Why not just start drawing?

That’s how our 2019 students began. We told them to draw something— literally anything. “Doodle,” we said. Fifteen minutes later their sketchpads were alive with fish and robots and half-human bat creatures—many of which became characters in their later comics. They learned about them by drawing them (the first homework assignment was fifty individual character sketches), not by describing them in words and then trying to translate those word-ideas into images.

Image First. That’s what I wanted to call the textbook. The introduction is a diagnosis for why Art departments have been more resistant to comics than essentially any other area in academia (including even Philosophy and Classics, where I had my first writing and classroom collaborations). The image-focused chapters are the cure.

After completing the first draft, I recognized that I was suffering from the passion of a convert, and so during revision we identified multiple approaches for creating comics:

Image-first (let the drawing process drive the story),

Story-first (the appropriate default setting for memoir),

Layout-first (there are more out there than you think),

Script-first (yes, it has its place too—though preferably not a medium-defining dominant one),

and Canvas-first (a smorgasbord of the best of the above).

Still, image-first is at the heart of book, providing a creative corrective for a script-dominated field. So instead of drawing from a prescribed script, the book explores the range of possibilities for how two juxtaposed images can interact—and having experimented with them all, artists can then select their favorite paths to continue down further. And each path has its own range of possibilities that we literally graph into units that can be shuffled, redrawn, reordered, and drawn again—always with new narrative effects emerging from the open experimentation. Instead of treating a comic as sequence of conceptually separate panels, we look at the page as a whole—because it is. A page is a canvas that must be understood as a single unit too. And if a canvas includes words, the artist-writer must consider how their renderings, placements, and interactions with images produces meanings distinct from words in a prose-only context.

Though our course is titled Making Comics, Making Comics is already an excellent book by Scott McCloud (2006)—and also now Lynda Barry (2019). I recommend them both—and also Abel and Madden’s Drawing Words & Writing Pictures. But they’re not sufficient. Barry’s is a brilliant (and for me emotionally moving) how-to for finding and unlocking a piece of your lost and probably somewhat damaged childhood self. Please read it. The others approach comics not as an open art form, but as a genre-shaped and industry-prescribed medium. That’s useful. But any conventions-first approach is also purposely limited. We tried to wipe the slate clean and identify a new set of underlying fundamentals.

Our subtitle changed too. Bloomsbury original asked for “A Writer’s and Illustrator’s Guide,” but reducing an artist to only an illustrator also reduces comics art to only illustrations, which illustrate words and ideas that exists before the image is created. Comics certainly can be that, but they can be more too.

Because we wanted to throw the widest possible creative net (because it increases the odds of individual artists discovering something new-to-them to explore and uniquely expand), we avoid historical and medium-based definitions of comics and accept that any two images placed next to each other could be a comic. Some scholars might flinch at the radical inclusivity (though as a scholar, I would have plenty more to say on the subject), but that concern is literally academic. Creating Comics is instead about the hands-on creative process, but with a birds-eye perspective of the sometimes-overlooked possibilities.

I’m also ridiculously proud of the fifty-or-so illustrations (and, since Creating Comics isn’t itself a comic, they really are illustrations). I’m a fledging digital artist, and so my contributions offer a fun contrast to Leigh Ann’s professional inks, but even better: the book is filled with artwork by our 2019 students. We were in the process of writing the first draft while teaching the second course, and as their comics began to emerge, we suddenly saw the obvious: they were already our collaborators. Without the course, we couldn’t have written the book, and our students’ artwork is the ideal document of the concepts and processes we describe.

And the grand finale: a 143-page anthology of comics excerpts by over forty comics artists, including Barry, Bechdel, Davis, Hernandez, Satrapi, Tamaki, Tomine—I need another post to give due credit, but flipping through the anthology probably provides the best lessons in comics-making that any textbook could offer. It’s pleasantly humbling to write what you hope to be the book for teaching comics and see it instantly overshowed by its own second half.

If you’re interested in a copy, the Bloomsbury site offers slightly lower prices (including a PDF) than at Amazon (though Amazon is worth a glance for the preview of the first 33 pages). If you’re thinking you might want to teach from it, the Bloomsbury site also lets you “Request exam/desk copy.” Also, if you’re interested in writing a book review, email: AcademicReviewUS@Bloomsbury.com (if you’re in North America) or AcademicReviews@Bloomsbury.com (if you’re anywhere else on the planet) to request a review copy.

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized