Monthly Archives: October 2016

31/10/16 Halloween Homage: Poe, the Grandfather of Superheroes

I taught a Satanist once. Nice kid, polite, well-spoken, adept with a monochromatic wardrobe. I was a new hire in a Virginia high school, so as far as I knew the whole building was slithering with demon-worshipping students and staff, but this kid (I’ve honestly forgotten his name) was the only one displaying The Satanic Bible on his desk. The weird thing was another kid (forgot his name too) sitting two seats down. The Bible on that desk was of the non-Satanic variety. Born Agains were common as Confederate flags (a group met every morning by the faculty parking lot to pray and smoke cigarettes), but this polite, well-spoken, fashion-neutral young man was joining the priesthood after graduation.

I figured God had been reading too many X-Men comics and wanted to see what a real-life Professor X vs. Magneto face-off looked like. He got His chance the morning of the first Poe assignment. I forget which title I’d typed on my English Honors syllabus, which body had been walled into which plot device, but discussion didn’t get far. The Satanist raised his hand first:

“This story portrays a man working to fulfill his highest human potential.”

The room was silent. The room was usually silent—it was first period—but normally all eyes didn’t swerve to stare at our future priest quite so intensely. He blinked, not certain he’d heard correctly, probably a mirror of my face. His arch-nemesis was ready to elucidate his opinion, but then God chickened out, booming His voice over the P.A. speaker. Actually it was the secretary’s voice, calling the Satanist down to the principal’s office. I literally never saw him again.

The priest went on to earn an A, and to write an end-of-year card thanking me, his agnostic teacher, for making room for Jesus Christ in his classroom (presumably because I’d allowed and even encouraged him to write all of his analytical essays on religious topics: Jesus and Hester, Jesus and Gatsby, Jesus and Lenny, etc.). I don’t think he believed me when I told him Poe was a Christian. I doubt the Satanist could have gotten his head around the yin and yang of that either. Poe, father of both detective fiction and science fiction, was a pro at combining opposing forces.

Scifi and detection may not patrol polar ends of the literary axis, but their rosters, unlike the X-Men’s and the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants’, don’t overlap. Detectives deal in crime, which means urban, which means right now. Expect grit in your blood puddles. Scifi is fantasy, is speculative, is otherworldly. Anything but the here and now. The tech is early Victorian, so you need a balloon to visit that city of telepaths on the moon. But Poe’s proto-Sherlock Dupin rarely leaves his Paris apartment, content to solve murders by combing clues from columns in The Daily Planet or its Parisian equivalents.

Of course the term “detective fiction” wasn’t coined till decades after Poe’s death, “science fiction” almost a century later, but like any good retcon, the memory of their non-existence has been lobotomized from the multiverse. Poe was a mostly monogamous author, so the mother of both his children was the Gothic. Scifi and DF, however, are promiscuous little brats, and so the family tree gets knotty before it sprouts capes and spandex. But let it be known: Poe is also the grandfather of the superhero.

If all genres are combinations of pre-existing elements, the superhero hails from an orgy. Scifi and DF hosted it at their private mad-house, Maison de Sante (later renamed Arkham Asylum). Guests arrived masked and scribbled “William Wilson” on their nametags. Except Hop-frog, a homicidal dwarf who burnt the building down, though not before the next generation of freaks was already gestating. There’s a reason Batman premiered in Detective Comics. Superheroes are fantastical detectives. They and/or their unearthly powers travel from far far away to fight crime in your urban backyard.

In addition to ballooning and ratiocinating, Poe’s superpowers included laying bricks, talking to mummies, pulling teeth, shadowing strangers, hunting pirate gold, blurting confessions, and hypnotizing corpses. He even pulled on a masque or two, but most of his guilt-hobbled monsters apprehend themselves. Dupin deduces a rare exception: the mother and daughter stuffed up a chimney in the Rue Morgue are the victims of (SPOILER ALERT!) an escaped orangutan. The revelation is as disappointing as it sounds, so you might want to skip ahead four and half decades; Arthur Conan Doyle’s knock-off detective is more beloved for a reason. Space tourism also spiked after Poe’s telescope hoax opened the first lunar Welcome Center. He even staffed it with actual batmen (“Vespertilio-homo”). Which is to say neither of his boys, Scifi or DF, were the sharpest quills in the proto-crayon box. They were just the first.

Poe never tried to browbeat them into the same story though, so no superpowered detectives for another century. No ultimate battles between Good and Evil either. God knows what Guidance was thinking when they scheduled a Satanist and an aspiring priest in my same English section. It was probably dumb luck, or the fated pull of opposites. I’m no Poe, but they might have made a dynamic duo with me as their mentoring mid-point. If only Hallmark made Lucifer-themed thank you cards.

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

24/10/16 Wonder Woman and Captain America Dismantle the Axis

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

17/10/16 Top 8 Superhero Comics, 2001-2016

My book editor wants an annotated list of “key works” for the superhero genre, and so here’s a draft of the third and final installment. The adjective “key” is intentionally ambiguous, and the focus is on authors. As before, I’m limiting myself to only four works per era. The Fourth Code Era begins when Marvel officially dropped the Comics Code in 2001, so the first time the Authority didn’t have authority over a majority of the industry. And the Post-Code Era begins in 2011 when DC dropped out too and the Code ceased to exist. We’re only five years into that current period, so the last four works here are the most tentative.

Fourth Code Era, 2001-2011:

Bendis & Gaydos’ Alias (2001-03). Brian Michael Bendis is one of the most prolific Marvel writers of the 21st century. He wrote Ultimate Spider-Man (2000-2009), has been the primary author of multiple Marvel cross-over event series, including Avengers Disassembled (2004), House of M (2005), Age of Ultron (2013), and Civil War II (2016), and as of 2016 was writing Spider-Man, Guardians of the Galaxy, and Invincible Iron Man. He partnered with artist Michael Gaydos to create Alias #1 (November 2001) through #28 (January 2004), after which he continued the characters Jessica Jones and Luke Cage in The Pulse and New Avengers. Gaydos, who also works in fine art and graphic design, renders his characters in a strikingly less idealized style than standard superhero comics art, with little or no attention to muscular and sexualization, while employing overlapping panel arrangements that highlight atypical amounts of undrawn gutter space. Gaydos’ approach parallels Bendis’ avoidance of standard superhero story tropes, including costumes and fight scenes. Alias is also notable as the first series published under Marvel’s MAX imprint, created for the equivalent of R-rated content when the company stopped working under the Comics Code. This series is collected under the title Jessica Jones: Alias, and Bendis and Gaydos reunited to continue the series in 2016.

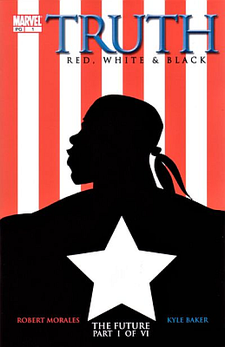

Morales & Baker’s Truth: Red, White & Black (2003). The idea of a World War II super-soldier program mirroring the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis experiments, in which the U.S. Public Health Service intentionally infected and left untreated hundreds of black men, originated from a comment made by Marvel publisher Bill Jemas to Marvel editor Axel Alonso (Carpenter 2005: 53-4). Alonso solicited a proposal from writer Robert Morales, and Kyle Baker, who had illustrated a Vibe Magazine comic strip with Morales, penciled and inked the series, #1 (January 2003) – #7 (July 2003). Alonso required changes when Morales’ script drafts veered too far from the Tuskegee events, but the tragic ending in which the black Captain America, Isiah Bradley, suffers permanent brain damage akin to Muhammad Ali, was Morales’ (Carpenter 2005: 54-5). The story is a uniquely grim but historically honest reimagining of Marvel’s Golden Age. Baker’s art is significant for stepping outside of the standard range of representational styles by taking the most overtly cartoonish approach in superhero comics at that time. The following year, Morales wrote eight issues of Captain America, with the last, #28 (August 2004), featuring both Steve Rogers and Isiah Bradley in the “Captain America & Captain America” cover banner and logo. Bradley’s appearance and the debut of his grandson, the Patriot, in Young Avengers #1 (April 2005) established the events of Truth within official Marvel continuity.

Simone’s Birds of Prey (2003-07, 2010-11). In 1999, Gail Simone co-founded the website Women in Refrigerators, which featured her list of dead or depowered female characters, created in response to Green Lantern #54 (August 1994) in which the hero finds his murdered girlfriend in his refrigerator. She wrote for Bongo Comics’ The Simpsons, and then for Marvel’s Deadpool in 2002, before moving to DC’s Birds of Prey in 2003. Simone wrote #56 (August 2003) to #108 (September 2007) of the first series, as well as #1 (July 2010) – #13 (August 2011) of the second. She significantly expanded the all-female cast and the role of Barbara Gordon, the original Batgirl, who leads the group as Oracle. Wheelchair-bound after the rape and maiming depicted in Alan Moore’s 1988 The Killing Joke, Oracle is one of the few disabled but non-superpowered superheroes in the genre. Simone collaborated with a range of artists, including penciller Nicola Scott who continued to work with her on her next project, Secret Six, in 2009. Simone also moved to Wonder Woman in 2008, becoming the title’s longest running female creator, Batgirl in 2011, and Red Sonja for Dynamite in 2013.

Rucka & Williams’ Batwoman (2009-10). Following the Neil Gaiman-scripted funeral of Batman in the previous issue, Detective Comics #854 (August 2009) – #863 (May 2010) featured the redesigned Batwoman as its cover series. Greg Rucka wrote all ten episodes, and J. H. Williams III penciled all but two. The original character was introduced in 1956 as a love interest for Batman and so arguably a response to Frederick Wertham’s claim that Batman and Robin were lovers. The rebooted lesbian character was introduced in 52 #7 (June) and as the cover feature of #11 (July 2006). She was DC’s highest profile LGBT character, a theme Rucka continues by introducing Police Captain Maggie Sawyer (a lesbian character created by John Byrne for Superman in 1987) as her long-term love interest. Williams’ use of two-page spreads and complex framing sequences are some of the most innovative layout designs since Steranko’s and Adams’ late 60s work. Batman returned as the cover feature of Detective Comics #864, and Batwoman, as co-written and drawn by Williams, moved to her own ongoing series with the one-off Batwoman (January 2011) and Batwoman #1 (November 2011). The Rucka-Williams’ Detective Comics #854-860 are collected under the title Batwoman: Elegy.

Post-Code Era, 2011-present:

Fraction & Aja: Hawkeye (2012-15). Matt Fraction, husband of fellow Marvel writer Kelly Sue DeConnick, wrote the complete series, #1 (October 2012) – #22 (September 2015), with several artists, including David Aja who penciled roughly half of the issues. Aja’s style is reminiscent of David Mazzuchelli’s Batman: Year One and Daredevil: Born Again art, but incorporates non-naturalistic elements of abstract signage and diagrams to innovative effect. The series was one of the most acclaimed during the period of its three-year run, especially #11, an episode told from the perspective of the main character’s dog, and #19, an episode told primarily in American Sign Language. Both Aja and Fraction worked and continue to work on a wide range of Marvel titles.

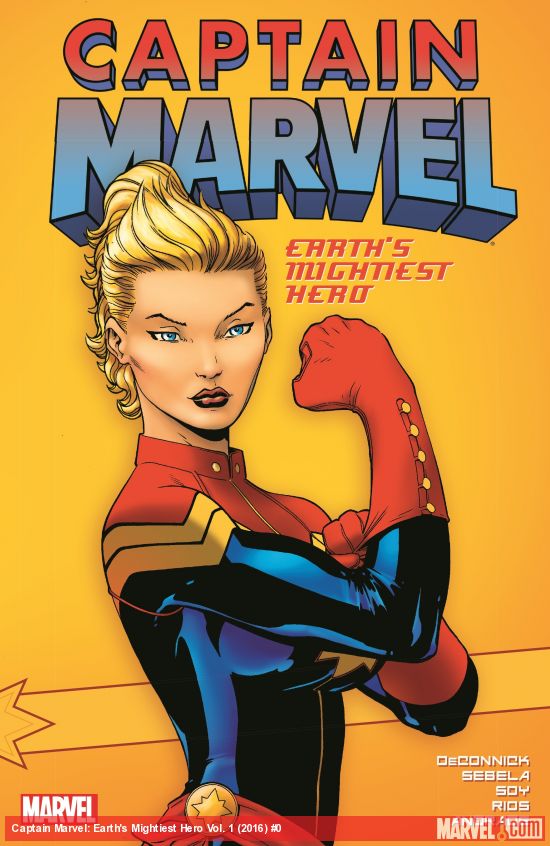

De Connick’s Captain Marvel: Earth’s Mightiest Hero #1-17 (2012-15). The original superhero Captain Marvel was created by Bill Parker and C. C. Beck for Fawcett Comics in 1939, after which DC sued for copyright infringement. The court battle continued until the early 50s, when Fawcett closed its comics division. Marvel later trademarked “Captain Marvel” by creating a new character with the same name in Marvel Superheroes #12 (December 1967). The supporting character U.S. Air Force Major Carol Danvers was introduced in #13, and, after developing her own superpowers, was reintroduced in her own series in Ms. Marvel #1 (January 1977). The character underwent a range of changes, until assuming her predecessor’s name in Captain Marvel #1 (August 2012). Working with a wide range of artists, DeConnick wrote the first series, #1-17 (January 2014), and continued through the second series, #1-18 (July 2015). DeConnick is one of the leading writers in contemporary comics; her other recent collaborations include Pretty Deadly with Emma Rios, Bitch Planet with Valentine De Landro, and Parisian White with Bill Sienkiewicz.

Wilson & Alphona’s Ms. Marvel (2014-15). After Carol Danvers relinquished the name in 2012, the new Ms. Marvel character and series debuted with #1 (February 2014). Kamala Khan, a Muslim teenager living in Jersey City, NJ, is the first Muslim character to lead a superhero series. The concept originated with Captain Marvel editor Sana Amanat, who grew up as a Pakistani-American Muslim in a predominantly white, Christian New Jersey suburb. She approached writer G. Willow Wilson, who was born in New Jersey and moved to Cairo after converting to Islam in her early twenties, and artist Adrian Alphona to create the series. Kamala Khan’s origin story both reiterates standard superhero tropes, while simultaneously overthrowing them, especially through Kamala’s relationship to her Pakistani parents and community. Alphona’s art departs from the comparably naturalistic of style of his 2003-04 Runaways in favor of a style that exaggerates human proportions and so offsets Kamala Khan’s shapeshifting ability. Alphona was the primary artist for the original run, drawing #1-5, 8-11, and 16-19. Wilson continued as writer of the ongoing All-New All-Different series beginning #1(January 2016), with Alphona appearing sporadically as a co-artist.

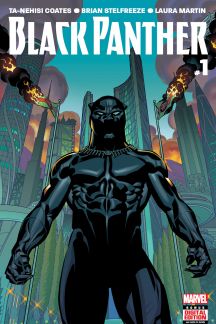

Coates & Stelfreeze’s Black Panther (2016-17). Journalist and senior editor Ta-Nehisi Coates is well-known for his articles in The Atlantic and New York Times. His Between the World and Me won the National Book Award for Nonfiction in 2015, the same year the MacArthur Foundation awarded him its renown “genius grant” and Marvel invited him to write an eleven-issue Black Panther series. Following an opposite trajectory as Neil Gaiman, who began in comics and established a high-profile literary career afterwards, Coates is the most prestigious author from outside of comics to enter the genre. He partnered with Brian Stelfreeze, a Marvel and DC artist since the early 90s. #1 (June 2016) premiered as one of the year’s top-selling comics, leading to a spin-off series, World of Wakanda, to be co-written by Coates, poet Yona Harvey, and fiction writer and essayist Roxane Gay, who is an associate professor of English and literary journal editor. Harvey and Gay are Marvel’s first female African American writers.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

10/10/16 Ralph Steadman and the Fear and Loathing of Typewriter Correction Fluid

Comics challenge traditional ideas of art.

Usually a statement like that implies “good art” or “high art” and the supposed challenge of whether comics as a mass medium can be included in such categories. They can and they do. But the challenge I’m talking about is less aesthetic and more metaphysical.

Comics artists create art in order to create comics. That sounds obvious enough, but unlike most art forms, the object the artist creates—the physical piece of paper with ink on it—is not the art. Traditionally, a comics artist draws on artboards, and then a printer uses those artboards to produce a comic. The comic is the work of art. The artboards can (and should) be called works of art too, but they’re not the art that is the comic–which, weirdly, has no original. A comic is its multiple copies.

Compare that to, say, Andy Warhol (who was all about the art of copies). If you buy a framed Warhol print—or button, postcard, or t-shirt—you don’t imagine you now own “a Warhol.” But if you buy a comic, you do own it. And, if it’s the first run of, say, Action Comics No.1, it’s worth as much as some Warhol originals. And yet, a copy of the cover of Action Comics No. 1 on a poster, postcard, or t-shirt is, like any Warhol copy, just a copy.

So some copies are copies and some copies are the thing itself. And that’s just a pleasant weirdness of comics. Except some of that weirdness bleeds back into the original art that isn’t the comic but is the comics artboard.

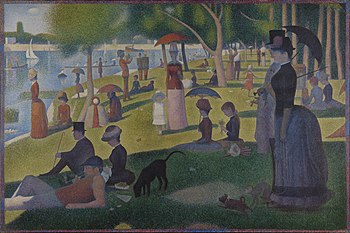

When I visited the Society of Illustrators as part of a recent research trip to New York, they were exhibiting a Ralph Steadman retrospective. Steadman began his career as a freelance cartoonist in the 60s for a range of English magazines–including Punch where, appropriately enough, the word “cartoon” originates. Before the first Punch cartoons in the 1840s, a “cartoon” was the cardboard-like material artists used for drawing architectural sketches. Neither kind of cartoon used to hang in art museums, which tend to prefer works like Georges Seurat’s “A Sunday Afternoon.”

Which is probably why I paused so long at Steadman’s parody:

It appeared in Town magazine in 1967. Or maybe only its reproductions did. Unless all those reproductions were the “cartoon” or “comic,” and the object hanging in the Society of Illustrators is something else–a work of art certainly, but not the mass produced “comic” that appeared in the magazine.

I realize I’m splitting metaphysical hairs here, but I ask because Steadman’s framed “original” is unlike most I’ve seen on a museum wall. Note these four spots:

Those are whiteout, something definitely not included on the gallery plaque underneath it:

That description, “Pen and Indian ink on paper,” should also include the word “collage,” since Steadman’s talk balloon and pointer are cut from a separate sheet of paper and affixed atop the larger sheet:

You might also notice the ghostly hint of letters behind the fully inked ones, so add “Pencil” to the list too. And it’s not just the Seurat parody. As I promenaded through the pictures in the exhibition, I found the same techniques used on nearly all of them:

Steadman even corrected his STEADmans:

Usually the glued paper and correction fluid is used for exactly that, corrections, ways to cover lines that he regretted drawing. But it’s more than stray lines and reshaped edges. He sometimes dropped in whole figures after the fact:

Usually the glued paper and correction fluid is used for exactly that, corrections, ways to cover lines that he regretted drawing. But it’s more than stray lines and reshaped edges. He sometimes dropped in whole figures after the fact:

The art term for such a correction is “pentimento,” Italian for “repentance,” what artists apparently experience when painting over what they wish that hadn’t painted in the first place. Except Steadman isn’t exactly “painting” in these cases. According to the wall plaque, his materials are only pen and ink. Because what curator, even one employed by the Society of Illustrators, is going to consider typewriter correction fluid an “art” material?

Which gets us back to metaphysics. Are these masterful objects hanging on the walls works of art themselves–or are they a stage of production in the process of creating the works of art that are the cartoons that appeared in the mass produced magazines? As I said already, of course they’re art–but the exclusion of the words “correction fluid” and “collage” also reveals a curatorly queasiness with their in-betweeness.

“Real” art–or “good art” or “high art”–would never include such materials because those materials reveal Steadman’s artboards as artboards. They’re not made for a gallery. They’re made for a printing press. Here’s one of Steadman’s most famous images of Hunter S. Thompson as it appears in its frame and as it appears on a gift shop shelf:

Setting aside the considerable fact that the “reproduction” includes color but the “original” doesn’t (imagine if Seurat or even Warhol left his colors to the whims of printers), notice what happens to all of those unsightly whiteout blotches:

They go from unsightly to unseen. Which of course is the point. Steadman’s work exists to be reproduced. In a very real and weird sense, the “Vintage Dr. Gonzo” postcard I brought home from the retrospective is closer to the intended work of art than the work of art hanging in the retrospective. So many of Steadman’s framed pieces include whiteout and scissored paper and erased pencil lines because those are the norms of artboards–and artboards aren’t the works of art he was intending to make. Each is an artifact of the process of making the mass produced image that in its multiple copies is the intended art.

The postcard cost me $1, but if you want to own a signed “original” (Four Color Silkscreen on White Rising Stonehenge Deckle Edge Paper, 19″ x 16″, Artist’s Proof Edition), it will cost you $6,000. Alternatively, you could find Thompson’s 1971 Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (first editions might go for about $1,250) and turn to page 79.

Arguably those mass produced illustrations are the “originals” too. Or you could find copies of the Rolling Stone issues that first featured Steadman’s “Gonzo” art:

There’s also a heavily STEADman-influenced comic book adaptation by Troy Little:

But that’s a metaphysical challenge for another day.

Tags: Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Ralph Steadman, Society of Illustrators, Troy Little

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized