Monthly Archives: June 2017

20/06/17 Evie Wyld and Joe Sumner’s “Everything is Teeth”

“It’s not the images that come first,” writes Evie Wyld in the opening sentence of her 2016 graphic memoir Everything Is Teeth. Wyld goes on to describe the sounds and smells of her childhood memories, but her first statement is also a metafictional nod to her collaborative process. Her cover credits artist Joe Sumner not as co-author but as illustrator in a font roughly half the size of Wyld’s, proportions that indicate that the story—the memoir content—is Wyld’s. And it is. At least on the surface. But Sumner’s images—even though they come second collaboratively—produce a far more complex and compelling work than if the memoir were Wyld’s alone.

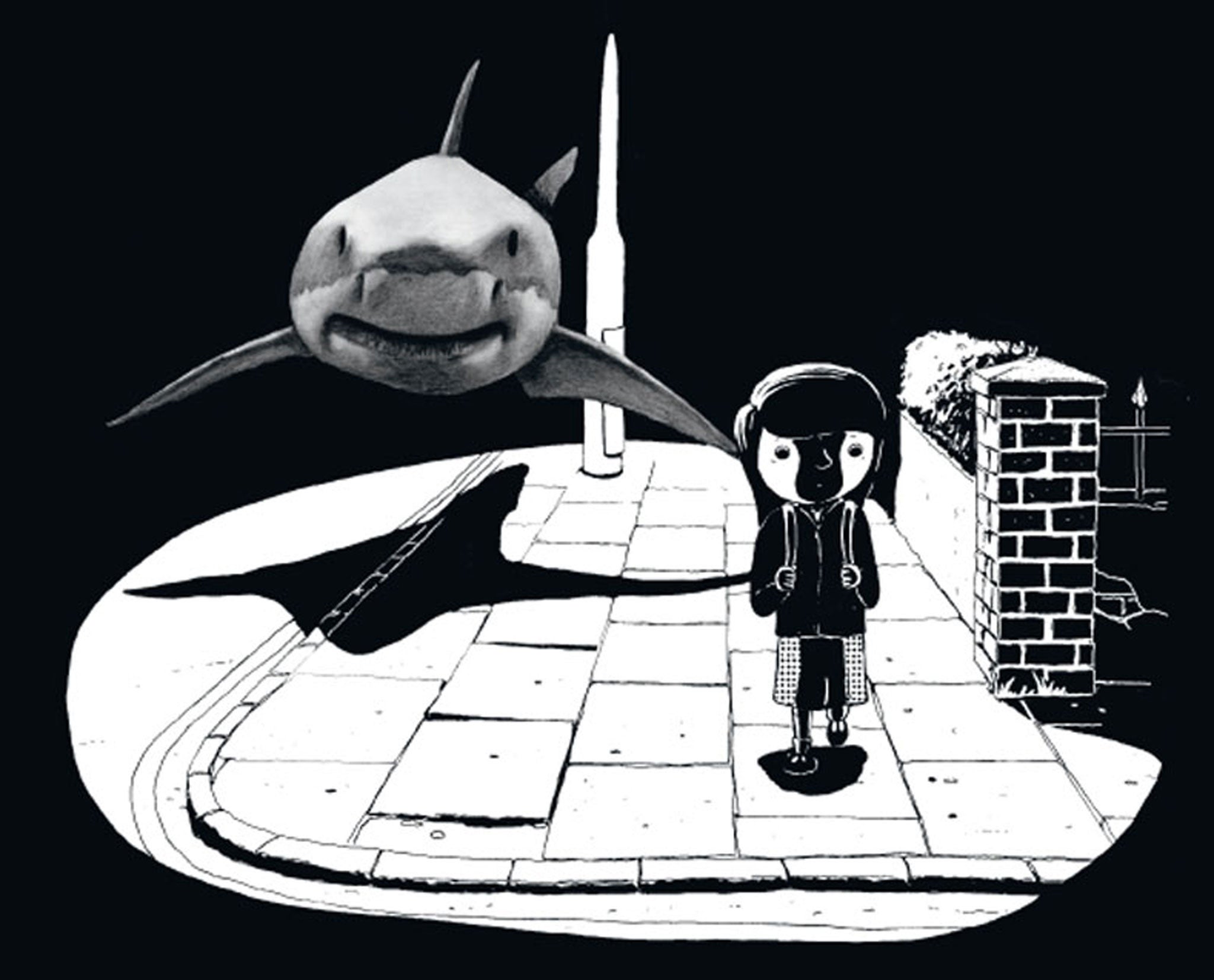

Sumner interprets Wyld’s words, and so her childhood world, in three scales. He renders the six-year-old Evie and her family members in traditional cartoon style: their heads and facial features are enlarged to impossible proportions, and their density of detail is minimal. Their environments, however, appear roughly naturalistic: trees, buildings, streets, even actors on TV screens have more realistic shapes and less simplified detailing. But the highest level of naturalism, at times achieving photorealism, Sumner reserves for images of sharks: the core subject of the memoir, the “something that lurks beneath the surface”.

Although contrasting, the two styles Sumner selects for characters and setting are a comics norm, common since Hergé‘s The Adventures of Tintin and Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy: cartoonishly simplified human figures who people comparatively detailed worlds. But not only does the realism of Sumner’s sharks exceed those norms, he often renders them within shared images to emphasize the impossible contrast.

Wyld’s opening sentence is offset by a country landscape and idyllic harbor—with the meticulous gray tones of a protruding fin shattering the flat black lines of the water’s surface. As the narrating Wylde alludes to undrawn stories about frightened relatives being alone on the water, Sumner instead depicts Evie discovering the simplistically drawn triangle of a shark tooth and carrying it home to show her family. The flat object only takes on shades of depth when it is part of the living, underwater animal.

Sharks are literally otherworldly. Their presence is not only an intrusion into Evie’s childhood reality, it undermines that baseline, revealing it be artificial, a willful illusion of simplicity that can’t be maintained in the presence of real-world threats. When Evie discovers the book Shark Attack!, its vivid renderings introduce the memoir’s first use of color beyond Sumner’s previously subdued yellows and blues. The pages come alive with a literal splash of red. Although Wyld describes a shark survivor’s torso-length scars as “a cartoon apple bite”, Sumner achieves the opposite effect: a photorealistic rendering of the horror that obsesses the child.

Wyld’s verbal images are simple and striking, too. Not only do sharks overturn rafts with “their shovel snouts” and a gored victim feel himself “loose in your skin suit”, but the mundane world is equally eloquent, her father’s skin “milk-bottle white” and her hair turning to “hot bread” in the sun. But nothing is more vivid than Sumner’s underworld of sea life, and the horror of that world proves to be much deeper than any sea.

Even little Evie seems to experience her shark obsession in relation to the mysterious, unexplained violence that lurks just beneath the adult world. She suffers visceral nausea at the family’s killing of a pregnant shark, even as Sumner draws her carrying two of the “puppies back home for frying”. Her father’s inexplicable work life and her mother’s casual insomnia are depths Evie can’t begin to fathom. Two pages after declaring a shark survivor to be “the greatest living man”, Evie’s brother comes home bloodied by bullies, a pattern that continues for much of his adolescence.

Relief seems to come with age, when Evie notices her brother “has become a foot taller than” their mother, but then aging becomes the ultimate threat. Sumner renders the death of Evie’s father in four, full-page images, textually juxtaposed with the now-adult Evie recalling the shark survivor and retroactively understanding the shark not as a monster but a “benign” if “indifferent” force. Her elderly father sits in a lawn chair, then in a hospital bed, until finally only his hat and sunglasses rest on a table framed in white on a black two-page spread.

Aside from two glimpses back into her childhood shark book, the world remains simple. Unlike the swimmer, her father’s struggle with death is a wordless cartoon. If death is the something lurking beneath the surface, it never breaks the water to reveal itself. It never provides the sufferer with a heroic struggle rendered in a more-real-than-real style. Even on his deathbed, her father cannot escape his caricature proportions: an absurdly large head with an absurdly large nose, only now framed in white rather than black lines of hair.

Wyld recounts only one incident in which she wasn’t present herself. “My parents,” she writes late in the memoir, “went deep-sea fishing a long time before I was born.” After catching fish after fish, everyone stopped and “watched mutely as a tiger shark, pale blue and clean, bigger than the boat, passed under, its fin skimming the hull.” Sumner draws the passengers in a thin strip at the top of the two-page spread, while giving nearly 4/5ths of the page space to the black water and the two largest and most fully detailed drawings of sharks in the memoir.

This oddly pivotal moment not only breaks chronology for the first and only time in the narrative, it also places Wyld’s text into the same ambiguous relationship to events as Sumner’s drawings. Like Sumner who receives Wyld’s memories only through her telling, Wyld received her parents’ memories of the fishing trip through their telling. But, like Sumner, Wyld goes beyond her source, rendering the story in her own vivid style. Her eloquence makes it her own—just as Sumner’s artistry makes Wyld’s story his own, too.

[The original version of this and my other recent reviews also appear in the comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Everything is Teeth, Evie Wyld, Joe Sumner

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

12/06/17 When Did the Hulk Become the Hulk?

After appearing gray-skinned in his premiere issue, the Hulk inexplicably turned green in his second. Though the color change had more to do with printing costs than storylines, the gray Hulk had a personality distinctly different from his later version. Marvel writers eventually retconned a distinct and separate character into the premiere issue, turning the gray Hulk into Gray Hulk AKA Joe Fixit.

When recalling creating the Hulk years later, Lee described the canonical green version: “I just wanted to create a loveable monster—almost like the Thing but more so … I figured why don’t we create a monster whom the whole human race is always trying to hunt and destroy but he’s really a good guy.”

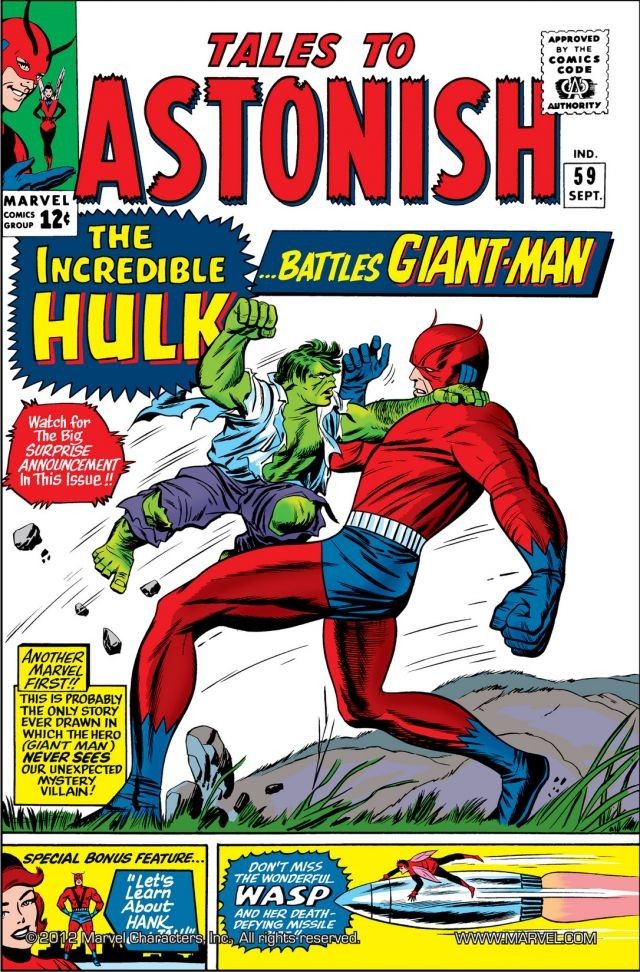

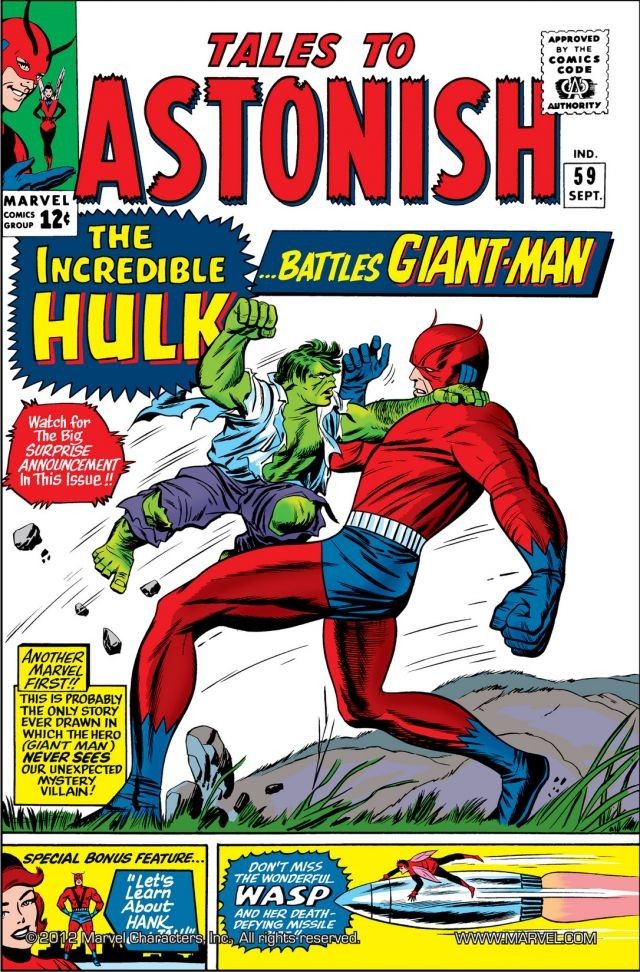

But even after The Incredible Hulk #1, the original Hulk was not loveable and was no good guy. He was a barely controlled monster who posed as a much of threat to the world as the supervillains he fought. After his original six-issue run and a few appearances in other titles, the Hulk’s cancelled series was renewed in 1964 as one of two ongoing features beginning in Tales to Astonish #59, with artist Steve Ditko replacing Dick Ayers for pencils beginning #60, and Jack Kirby co-penciling with multiple artists beginning #68. Stan Lee was credited for all writing, but because of the so-called “Marvel Method” much of the uncredited and unpaid co-writing fell on the pencilers.

The 1964 Bruce Banner no longer uses his Gamma Ray device to transform into the Hulk, and when Giant-Man comes searching, Banner thinks, “So! The Avengers are still seeking the Hulk, eh? Will they never leave him in peace?”, reflecting the early stages of Lee’s revision. The Hulk himself later laments: “There is nothing for Hulk—nothing but running—Fighting! Nothing—” (#67). The character is still antagonistic and can take “off like a missile”, but he saves Giant-Man when both are targeted by an atomic shell, also throwing it to explode far from the nearby town (#59). The Leader, the primary antagonist from #62–75, was “an ordinary laborer” until yet another “one-in-a-million freak accident occurred as an experimental gamma ray cylinder exploded” transforming him into “one of the greatest brains that ever lived” (#63). Also, as earlier, Banner gains control of the Hulk’s body for several episodes, continuing the struggle of the 1962 series.

After the January 1966 issue, however, the premise changes. When the military fires Banner’s experimental “T-Gun,” the Hulk is sent to “some far distant future,” a “dead world” in which Lincoln’s memorial statue sits in the ancient ruins of Washington, D.C. (#75). A future commander declares: “We cannot allow a destructive, rampaging brute to run amok in our land!” (#76). This “grim, ominous war-torn world of the far future” recalls Kennedy’s 1963 “war makes no sense” refrain, and when the Hulk returns from it to his own time, he settles into a new, toddler-like personality, no longer posing a threat unless attacked.

Moreover, as with the Thing and his love interest Alicia, Banner’s girlfriend, Betty Ross, views the Hulk in transformative light: “His arms—so huge—and brutal—but yet, so strangely gentle—!” (#82). Although he has brought her to an isolated cave, she adds: “It’s strange! I find I’m not afraid of him any longer! As powerful, and as unpredictable as he is … I can’t help feeling he’s not truly evil!” (#83).

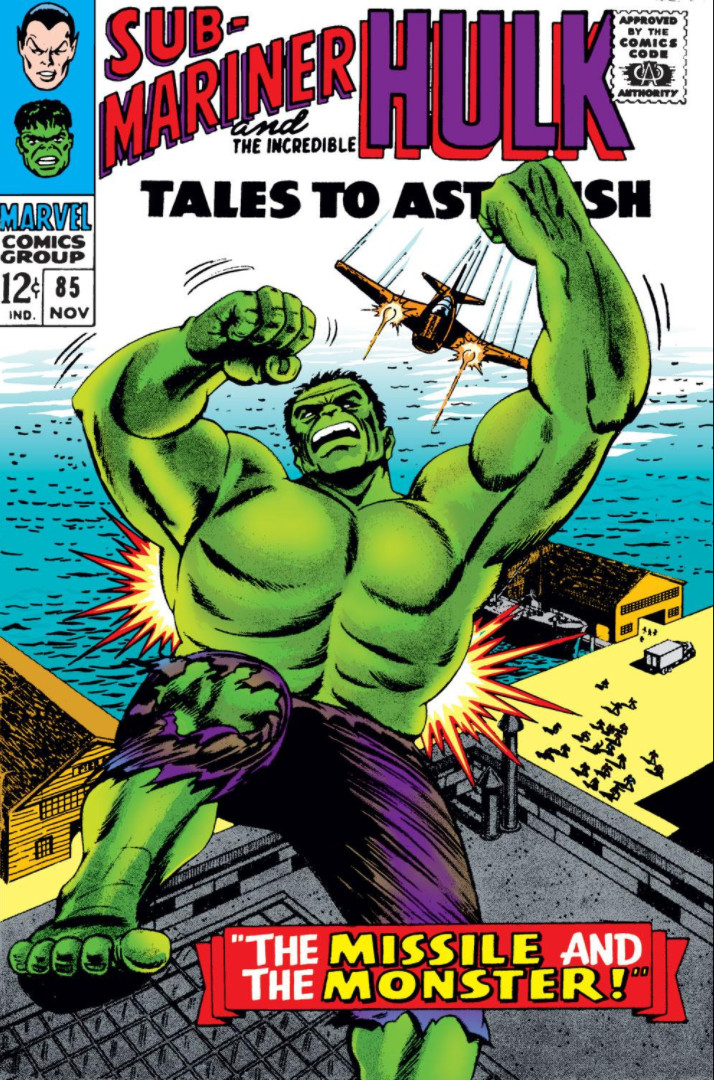

Even General Ross, who has hated and hunted the Hulk since his debut, changes attitude: “The strongest … most dangerous being on Earth … but my daughter tells me he rescued her … tells me she loves him …! And yet … somehow … I find myself beginning to understand”. When the military test fires another of Banner’s weapons, an “anti-missile proof” missile and so “the greatest weapon of all!” (#85), the Hulk prevents it from destroying New York.

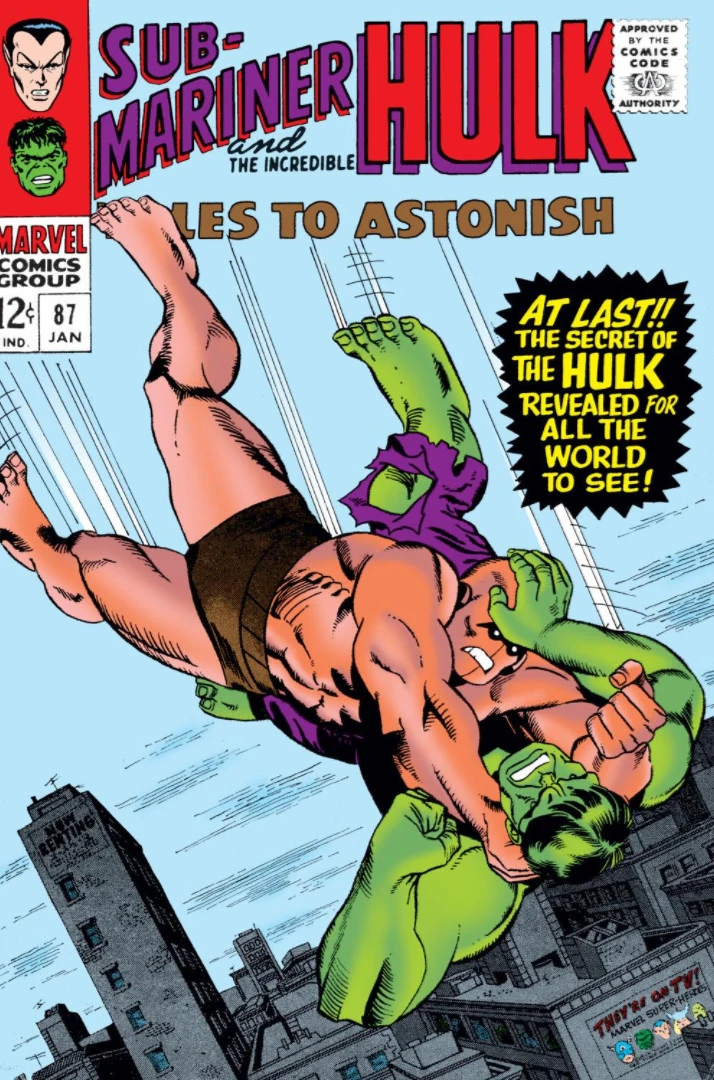

With the Hulk’s secret identity no longer a secret, Betty declares: “Now there can be no doubt! The Hulk isn’t a monster—he never was! He was always you!” (#87), and her father now asks for Banner’s help in stopping the next menace and praises the Hulk because “he saved us—from our own folly!” President Johnson sends General Ross an executive order: “If, in your opinion, the Hulk is no longer a menace, you are authorized to grant him full and immediate amnesty, clearing him for all guilt, or suspicion of same,” but because a villain tricks the Hulk into a rampage Ross shreds the order (#88).

Though the Hulk remains an outcast, the ongoing narrative permanently shifted. Like the X-Men who are also distrusted and pursed by government figures, readers understand the government to be definitely wrong. By losing its monstrous ambiguity, the Cold War superhero formula regained its original Golden Age status of misunderstood hero.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

05/06/17 Rereading The Incredible Hulk #1-6 (1962)

Stan Lee predicted in his original 1961 Fantastic Four synopsis that the unpredictable and monstrous Thing would prove to be the most interesting character to readers. He was right—so much so that after four issues, Marvel premiered a new title that featured a main character based on the Thing:

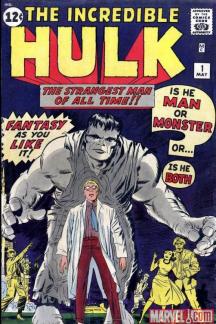

The first cover of The Incredible Hulk makes the monster motif explicit, asking “Is he man or monster or … is he both?” Lee combined the standard superhero alter ego trope with the uncontrolled transformations of a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Kirby models the Hulk on Boris Karloff in the 1931 Frankenstein. Like those mad scientists, Dr. Bruce Banner is “tampering with powerful forces,” only now his hubris transforms himself into his own monstrous creation. The opening panel features “the most awesome weapon ever created by man—the incredible G-Bomb!” moments before its “first awesome test firing!” Kirby draws its creator with a “genius” signifying pipe as he takes “every precaution,” even as General Ross insults him for cowardly delays. Though Banner risks his life to save Rick, a teenager who has driven onto the bomb site, that kindness is erased by the Hulk who, after his first Geiger-counter-triggering transformation, swats Rick aside, uttering his first words: “Get out of my way, insect!” Lee likens him to a “dreadnought,” the twentieth-century’s most massive battleships, and soon he is speaking like a supervillain, “With my strength—my power—the world is mine!,” and threatening to kill Rick to keep his identity a secret.

The first issue would be a complete repudiation of the superhero formula if not for the late entrance of another “brilliant” scientist-turned-radioactive-monster; the Soviet Union’s Gargoyle captures the Hulk, threatening the balance of power: “If we could create an army of such powerful creatures, we could rule the Earth!” Like the Hulk, the Gargoyle is controlled by no nation, savoring that his “cowardly” comrades and “some day all the world will tremble before” him.

The Gargoyle is stopped not by the Hulk’s might, but Banner’s “milksop” kindness, reversing the Clark Kent trope that had defined the superhero genre for two decades. The crying Gargoyle would “give anything to be normal!” as Kirby draws him shaking his fist at a portrait of Khrushchev because he became “the most horrible thing in the world” while working “on your secret bomb tests!” As a result, he accepts Banner’s offer to cure him “by radiation,” and in turn destroys the Soviet base and rockets Banner and his sidekick back to the U.S.: “So we’re saved! By America’s arch enemy!” Although Banner hopes for the end of “Red tyranny,” he remains “as helpless as” the Gargoyle against his own “monster”.

In addition to changing from gray to green, in the second issue, the Hulk seizes control of an alien spaceship to use it for his own purposes: “With this flying dreadnaught under me, I can wipe all of mankind!” and it is again Banner, using his “Gamma Ray Gun” invention, who stops the alien invasion.

These are not the tales of a standard dual-identity superhero, but a Clark Kent battling both external threats and his own supervillainous alter ego. Steve Ditko inked Kirby’s pencils for the second issue, cover-dated July 1962, a month before the premiere of Lee and Ditko’s Spider-Man in Amazing Fantasy #15. Ditko’s Hulk bore an even greater semblance to Karloff, and now Peter Parker looked like a younger version of Bruce Banner. The Hulk does not begin to resemble a superhero until the following month.

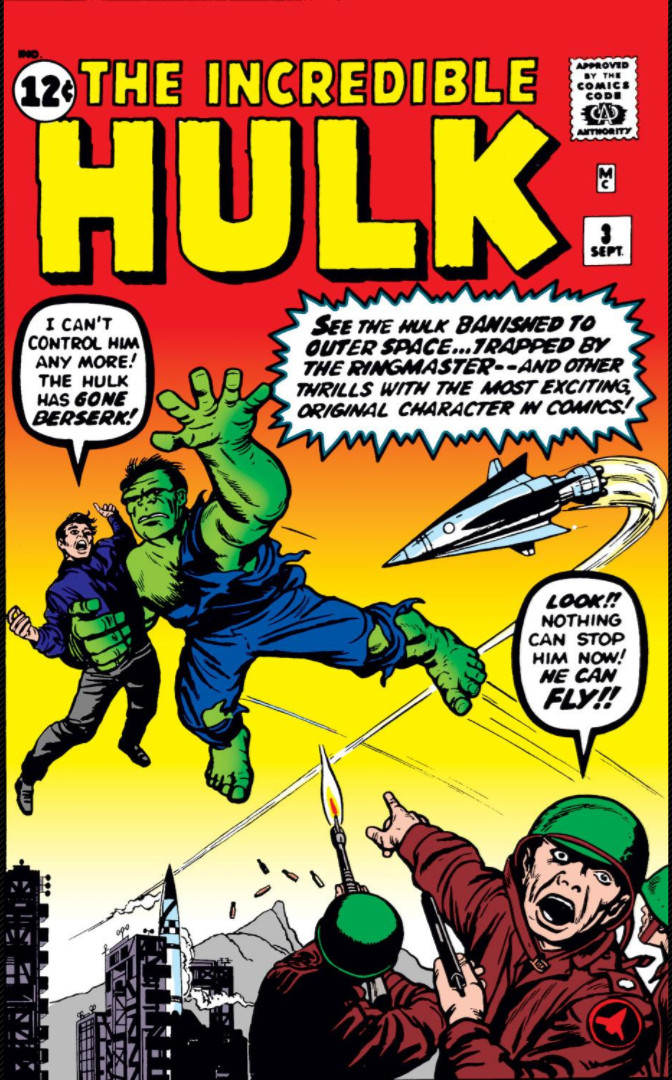

In the third issue, the military attempts to destroy the Hulk by launching him into the same radiation belt that created the Fantastic Four, but instead his transformations, which were previously trigged by nightfall, become unpredictable. Rick briefly gains hypnotic power over the “live bomb” of the now golem-like Hulk, evoking another admonitory fable: “It’s too much for me! I’ve got the most powerful thing in the world under my control, and I don’t know what to do with it!”

Kirby and Lee could not settle on a clear premise, with the Hulk changing personalities and transformation plot devices every other issue. In the fourth issue, Banner invents a self-radiating machine in order to “regain the Hulk’s body—but with my own intelligence,” which, though seemingly successful, creates a “fiercer, crueler” version of Banner inside a Hulk who is still “dangerous” and “hard to control.”

The new Hulk no longer tries to kill Rick, but now speaking like the Thing, he tells him to “Shut your yap” and to “get outa my way!” before foiling the Soviets’ next attempt to capture him and again build “a whole army of warriors such as you!” Though he prevents another invasion, this time by an underground race led by an ancient immortal tyrant, the Hulk ends his first adventures in the following issue articulating his defining nuclear allegory: “Let ‘em all fear me! Maybe they got reason to!” In the issue’s second story, he thwarts a Chinese Communist general, and yet the Hulk insists that “the weakling human race will be safe when there ain’t no more Hulk—and I’m planning on being around for a long time!!!”

By the sixth issue, the last of the original, one-year title run, the Hulk has reverted to a supervillain and considers teaming-up with an invading alien against the human race “to pay ‘em all back!” Though the Hulk ultimately defeats the alien, winning a pardon for his past crimes, Banner has less and less control of his transformations, suffering delayed and partial effects with Banner briefly retaining some of the Hulk’s strength and, more bizarrely, with the Hulk briefly retaining Banner’s face. Rick concludes: “The Gamma Ray machine—it grows more and more unpredictable each time it’s used! If Doc has to face it again—what will happen next time?”

“Next time” was delayed by over a year, after the Cuban missile crisis led to a paradoxical drop in Cold War anxieties. After a few appearances in other titles including The Avengers, the Hulk and his cancelled series were renewed in 1964 as one of two ongoing features beginning in Tales to Astonish #59. Both the Gamma Ray machine and Banner’s unpredictable transformation were forgotten, and the Hulk soon evolved into the canonical version of the character: a well-intentioned but toddler-minded creature misunderstood and mistreated by the authorities.

Tags: 1962, Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, Steve Ditko, The Incredible Hulk

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized