Monthly Archives: January 2014

27/01/14 Tibet, Superhero Tourist Destination of the World

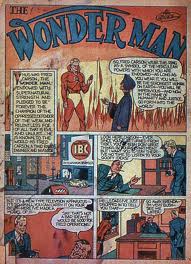

Zarathustra came down from the mountain in 1883. He’s Nietzsche’s reboot of the ancient Iranian prophet Zoroaster—which means the first Superman came down from a mountain in Asia. It’s been a popular continent for superheroes since. When DC rival Fox Publishing needed a Superman knock-off, artist Will Eisener sent Wonderman to Tibet where a turbanded Tibetan was handing out magic rings.

Wonderman couldn’t survive the kryptonite of DC’s court injunction, so for Wonder Comics No. 2 Eisner swapped the colored tights and briefs for a tuxedo and amulet-crested turban. Yarko the Great was one of a dozen superhero magicians to materialize in comic books over the next three years. Nine of them shopped at the same turban store—though Zanzibar the Magician got confused and grabbed a Turkish fez instead. Three of them imported Asian servants too.

The tights-and-brief crowd rallied and sent a half dozen new supermen East, three specifically to Tibet, with Egypt as a solid runner-up. My favorite, Bill Everett’s Amazing Man, is almost as naked as his earlier Speedo-sporting Sub-Mariner, but Amazing Man has the power of the Tibetan Council of Seven on his side. He could also turn into “green mist,” which must have annoyed the hell out of the Green Lama. Jack Cole threw in a Fu-Manchu supervillain too: the Claw attacks America from “Tibet, land of strange religions and mysterious customs.”

When Stan Lee’s boss gave him the same assignment (do what DC is doing), he bee-lined back to Tibet for his and Jack Kirby’s first (and mostly forgotten) attempt at a superhero, the 1961 Doctor Droom. Kirby even gives the formerly Caucasian physician slanted eyes and a Fu Manchu moustache as his lama explains: “I have transformed you! I have given you an appearance suitable to your new role!”

Droom flopped, so Kirby sketched an iron mask and Lee dropped the “r” and, voila!, the supervillainous Doctor Doom was born. The following year Doom was “prowling the wastelands of Tibet, still seeking forbidden secrets of black magic and sorcery!”Another year and Doctor Strange returns from Tibet as “Master of Black Magic!” Strange also picked up Wong, one of those handy manservants Tibetans hand out with their superpowers. The third Doctor emptied Lee’s Tibetan well, but Roy Thomas and Gil Kane’s Iron Fist kept Orientalism thriving at Marvel into the 70s.

Over at Charlton Comics, Peter Morisi’s Thunderbolt returned from his Tibetan adventures with the standard superhero package. Since Alan Moore’s Watchmen were borrowed from Charlton characters, twenty years later his Ozymandias not only “traveled on, through China and Tibet, gathering martial wisdom” but was “transformed” by “a ball of hashish I was given in Tibet” and next things he’s “Adopting Ramses the Second’s Greek name.” Even the 21st century Batman, as retooled in Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, hops over to the Himalayas to learn his chops from yet another monkish mentor. And you’ll never guess where director Josh Trank sends his teen superhuman for the closing shot of the 2012 Chronicle.

The 1930s mystery men loved the Orient too. Before Walter Gibson’s Shadow emigrated from pulp pages to radio waves, he first “went to India, to Egypt, to China . . . to learn the old mysteries that modern science has not yet rediscovered, the natural magic.” When Harry Earnshaw and Raymond Morgan conjured Chandu the Magician for film serials, they sent their secret agent to India to study from another batch of compliant yogis. And not only did Lee Falk’s comic strip do-gooder Mandrake the Magician pick up his powers in Tibet, his Phantom found his dual identity in the India knock-off nation of “Bengalla” (which magically wanders to Africa in later stories).

Before Doctors Strange, Doom and Droom (not a practice included in Obamacare) earned their degrees in Tibet, Doctors Silence, Van Helsing and Hesselius interned their first. You can add Siegel and Shuster’s pre-Superman vampire-hunting Doctor Occult to the list of eligible providers too. Like those turban-obsessed magicians, these world-touring physicians are armed with Oriental knowhow. Algernon Blackwood’s Silence was a 1908 mummy-battling best-seller, cribbed from Bram Stoker’s 1897 Dracula. Stoker’s Van Helsing is an expert on “Eastern Europe” and labels his vampire nemesis “a man-eater, as they of India call the tiger who has once tasted blood of the human.” Joseph Sheridan LeFanu’s 1872 Dr. Hesselius hunts vamps too, but his first patient is an English reverend driven to suicide by visions of “a small black monkey” caused by his addiction to the “poison” green tea imported from China, ever the land of strange religions and mysterious customs.

Since none of the doctors bother to mention their mentors, the ur-guru award goes to Rudyard Kipling’s 1901 Kim. While no superhero, Kim is the prototypical colonial adventurer, and Kipling supplies him with his very own “guru from Tibet,” one who conveniently needs an English boy (for some reason Asian kids won’t do) to achieve his life-long spiritual quest. Kim in turn treats the guru “precisely as he would have investigated a new building or a strange festival in Lahore city. The lama was his trove, and he purposed to take possession.” Which soon became official policy for all aspiring superheroes trawling the Orient for superpowers. Kim and his guru even prefigure Batman and Robin—only reversed, since Asian mentors are just like underage sidekicks.

Despite Kim’s Superman-like influence on the genre, even Kipling has his predecessors. The first superhero to pinch his powers from an obliging Oriental is Spring-Heeled Jack. The masked Victorian used to leap through a dozen plays, penny dreadfuls, and dime novels. I like the Alfred Coates 1886 version. Jack’s dad reaps his fortunes in colonial India, and Jack returns to England with the workings of a “magical boot” that “savoured strongly of sorcery.” Jack “had for a tutor an old Moonshee, who had formerly been connected with a troop of conjurers—and you must have heard how clever the Indian conjurers are. . . Well, this Moonshee taught me the mechanism of a boot which . . . enabled him to spring fifteen or twenty feet in the air.” That old Moonshee (Jack must mean “munshi,” an Urdu word for writer that the Brits decided meant all clerks) is the first incarnation of Wonderman’s turbaned Tibetan.

The endlessly exotic Orient, the planet-spanning ring of Britain’s 19th century frontier. A superhero is the ultimate colonialist, seizing his fortunes in faraway lands and shipping them home to maintain his nation’s status quo, its global supremacy. It used to be the British Empire, then the American, but superheroes are always the imperial guard.

While Eisner’s imaginary Tibetan was handing out magical treasure in 1938, real Tibetans were arguing national autonomy with China and rights of succession with warring regents. Unlike Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, the actual Zoroaster did not declare, “God is dead.”He was all about exercising free will in the service of divine order and so becoming one with the Creator. I’ve not read any of his surviving texts, and I seriously doubt Nietzsche did either. I’ve also never set foot in Asia—though I did gaze at it from a cruise ship docked in Istanbul once, and that’s a lot closer than most comic book readers ever get.

[For more on this topic, my related essay, “The Imperial Superhero,” appears in the new PS: Political Science & Politics, as part of an eight-article symposium on the politics of the superhero.]

Tags: Nietzsche, Orientalsim, Will Eisner, Wonderman, Zoroaster

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

20/01/14 School for Batman

What do you want to be when you group up? My daughter, like lots of teens, has been fielding that question since she was two. She’s looking at colleges now, so the question has morphed into “What do you want to major in?” But she told me that her answer, her secret answer, the heart of hearts answer she’ll never write on any application form, hasn’t changed since she wore big girl pull-ups:

“Batman.”

That’s still the first word that pops into her head. “Astronaut” is the second. But Batman is better. “He doesn’t have X-ray vision or any other crazy powers,” she says, “but he still spends his life and money helping people.” Also the Batmobile is really cool. And his ears. My daughter has always thought the bat ears on his hood were cute. She used to chew on them. The dolls in our attic have her teeth marks.

Several graduate and undergraduate programs in comic book studies have popped up since she stopped hosting tea parties with action figures, but to the best of my knowledge, no school offers a major in Batman. Not even mine. We live a five-minute stroll from campus, so my daughter would rather blast off to an alien planet than stay in our Virginia smallville for college. Her brother is still in middle school, and still peruses the occasional comic book from my childhood trove. He’s gnawed on his fair share of attic superheroes, but I suspect he’ll be feeling the warmth of alien suns soon too.

Which means neither will get to take my Superheroes course. I’m teaching it for the fifth time this spring. It spawned back in 2008 when a group of honor students were scouring campus for a professor willing to design and teach a seminar on superheroes. They’d suffered a few rounds of blank stares and grinning rejections when they wandered into my wife’s office. She was chairing our English department at the time, and you’ll never guess whose office she sent them to next. I said yes. Of course I said yes. I’d always enjoyed comics as a kid and then with our own kids. Now I’d just augment that with a bit of research.

My wife doesn’t regret her choice, but neither of us predicted the black hole-sized obsession the topic would open in me. Conference panels, print symposiums, international journals, radio interviews, cybercasts, newspaper op-eds, lit mags, one-act festivals, my appetite for cape-and-mask forums keeps expanding. When my wife and another good friend spurred me to start a blog, neither had superheroes in mind then either. I could blame those meddling honors students, but that first class of sidekicks flew off to solo adventures years ago. I’m the one who keeps offering revised versions of the course every year while posting blog links on campus notices once a week.

The first day of ENG 255 usually begins with some polite but bemused variation on “Why superheroes, Professor?” Colleagues ask me the same, only with the preface “Don’t take this the wrong way but.” The short answer is easy. Superheroes, like most of our pop culture productions, reflect who we are. And since superheroes have been flying for decades, they document our evolution too. On the surface of their unitards, they’re just pleasantly absurd wish-fulfillments. But our nation’s history of obsessions broils just under those tights: sexuality, violence, prejudice, politics, our most nightmarish fears, our most utopian aspirations, it’s all swirling in there. But you have to get up close. You have to be willing to wrestle a bit. I think we should pull on Superman’s cape. I think we all need to sink our teeth into Batman’s head.

Spring registration at Washington & Lee University starts soon. I have yet to work visiting superhero poet Tim Seibles into the schedule yet, but for interested students and the occasional scholar who’s asked me for a copy, here’s the syllabus-in-progress:

ENGL 255: Superheroes

The course will explore the early development of the superhero character and narrative form, focusing on pulp literature texts published before the first appearance of Superman in 1938. The cultural context, including Nietzsche’s Ubermensch philosophy and the eugenics movement, will also be central. The second half of the course will be devoted to the evolution of the superhero in fiction, comic books, and film, from 1938 to the present. Students will read, analyze, and interpret literary and cultural texts to produce their own analytical and creative works.

Texts:

The Scarlet Pimpernel, Baroness Orczy

The Adventures of Jimmie Dale, Frank L. Packard

Gladiator, Philip Wylie

Superman Chronicles, Vol. 1, Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster

Batman Chronicles, Vol. 1, Bob Kane, Bill Finger

Wonder Woman: The Greatest Stories Ever Told

Marvel Firsts: 1960s

Soon I Will Be Invincible, Austin Grossman

Missing You, Metropolis, Garry Jackson

Additional texts:

Spring-Heeled Jack, Anonymous

(excerpt from) Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Frederick Nietzsche

“The Revolutionist’s Handbook,” George Barnard Shaw

(excerpt from) Tarzan of the Apes, Edgar Rice Burroughs

(excerpt from) A Civic Biology Presented in Problems, George Hunter

“The Reign of the Superman,” Jerry Siegel

(excerpt from) The Clansman, Thomas Dixon, Jr.

“A Retrieved Reformation,” O. Henry

(excerpt from) The Curse of Capistrano, Johnston McCulley

“The Girl from Mars,” Jack Williamson and Miles J. Breuer

(excerpt from) Alias the Night Wind,

“Don’t Laugh at the Comics” (1940), William Moulton Marston

“The Sad Case of the Funnies” (1941), James Frank Vlamos

“Why 100,000 Americans Read Comics” (1943), William Moulton Marston

(excerpt from) Love and Death: A Study in Censorship (1949), Gershon Legman

Comics Code Authority Guidelines

“Secret Skin: An essay in unitard theory” (2008), Michael Chabon

VQR Spring 2008 Superhero Stories

Films:

The Mark of Zorro (1920)

The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934)

The Gladiator (1938)

Look, Up in the Sky! The Amazing Story of Superman (2006)

Comic Book Superheroes Unmasked (2003)

Unbreakable (2000)

Hancock (2008)

Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog (2008)

Radio:

The Shadow, The Blue Beetle

Writing Assignments:

1. Two 4-page analytical essays examining assigned texts on topics of your design.

2. A 6-page essay combining creative and analytical writing. You will invent superheroes and discuss the characters’ relationships to the history of the genre, responding to specific literary and cultural elements of the evolving formula.

Week One

Mon

*early afternoon film: Look, Up in the Sky! The Amazing Story of Superman (2006)

Tues Superman Chronicles; “Don’t Laugh at the Comics”

Wed eugenics chronology; Nietzsche Zarathustra (excerpt); Shaw Handbook (excerpt); Tarzan (excerpt); Civic Biology (excerpt); “The Reign of the Superman”; Nazi response to Superman; selected historical newspaper article

Thurs Spring-Heeled Jack; The Scarlet Pimpernel (chapters 1-14);

Fri Scarlet Pimpernel (complete); The Clansman (excerpt);

*early afternoon essay conferences

Week Two

Mon rough draft of 4-page essay due

Radio serial: The Shadow

* optional paper conferences after class

Tues Jimmie Dale (Chapters 1, 2, ?, 11, and one additional story); “A Retrieved Reformation”;

“Murder by Proxy”

* early afternoon film: The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934)

Wed final draft of essay due; The Curse of Capistrano (excerpt)

Early morning film: The Mark of Zorro (1920)

Thurs Gladiator (Chapters 1-11); “The Girl from Mars”

Fri Gladiator (complete); Alias the Night Wind (excerpt)

* early afternoon film: The Gladiator (1938)

Week Three

Mon Batman; “The Sad Case of the Funnies” (1941); “The Shadowy Origins of Batman”

Radio serial: Blue Beetle

Tues rough draft of 4-page essay due

*early afternoon film: Hancock (2008); begin superhero project

Wed NO CLASS; individual essay conferences

Thurs final draft of essay due; “Secret Skin”

morning film: Comic Book Superheroes Unmasked (2003)

Fri Wonder Woman; “Why 100,000 Americans Read Comics” (1943)

Week Four

Mon Marvel Firsts (selections); Comics Code; preliminary draft of superhero

*early afternoon film: Unbreakable (2000)

Tues Soon I Will Be Invincible (Part One, to p. 153) [BEGIN CLASS AT 9:00]**

*7:00 Austin Grossman reading, Northen Auditorium

Wed Soon I Will Be Invincible (complete)

Austin Grossman class visit

presentations of superheroes

*early afternoon conferences

Thurs VQR Spring 2008 Superhero Stories

presentations of superheroes

Fri Missing You, Metropolis

presentations of superheroes

* Superhero poster exhibition at the library during the Spring Term Festival from 12-3

Sat Final draft of project due 12:00 at my office

Tags: English 255 Superheroes, syllabus, Washington and Lee University

- 4 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

13/01/14 How to Teach Zombies

Zombies stumble into my class all the time. They tend to be friendly but a little lost, uncertain whether they belong in a fiction workshop. They stare blankly when I explain that the course is focused on “literary” fiction, a species of writing they’ve heard of but only sporadically consumed.

It’s not an easy term to digest. Adam Brooke Davis, in his recent essay “No More Zombies!,” divides “the playfulness that is above seriousness from the drivel that is below it” by banning all “alt-worlding” from his advanced writing workshop and requiring his students to write about “real environments with real people, facing [real] problems.” So “literary” is narrative realism, and everything else is genre (sci-fi, fantasy, horror). Those are pretty much the definitions the publishing industry has been using for decades.

It sounds good, but when I open up a collection of O. Henry Prize-winning stories I find a range of alternate worlds. They involve androids, a village on the back of a whale, and a giant square from space that slowly crushes a town. If I reach to my next shelf, I can pull down a dozen top-tier literary journals that include equally nonrealistic stories, all quite serious and drivel-free. The range of narrative realism in the same issues is serious and drivel-free too. A story’s setting, real or speculative, predicts nothing.

Yet Davis bemoans the influence of pop culture, believing that all the alt-worlds infecting film, TV, and popular literature have mutated his students into lazy zombies instead of disciplined writers. If so, it’s got nothing to do with “alt-worlding”—all fiction writing is alt-worlding. There is no such thing as a work of fiction that takes place in the real world. Stories exist solely in words. That’s an unbelievably obvious fact, but even creative-writing professors can lose track of the implications.

A work of narrative realism is no closer to being “real” than a story about vampires, superheroes, or anthropomorphic chipmunks. By “real,” we usually mean “familiar,” sometimes lazily so. If a first sentence describes a pickup truck grinding over gravel, rather than a hovercraft quivering above landing lights, we perceive the story as existing “here” and “now,” not in some other place and time. The implied world is a ready-made. Instantly recognizable environments, Davis implies, force students to focus on more important story elements.

Sometimes that’s true. But if handed a choice, I will sooner read a student draft that takes place on a distant planet in a far-flung future than a story set in a campus dorm last weekend. Neither setting is intrinsically better, but even the most experienced writer needs some psychic (and so probably physical and temporal) distance to transform real experience into “realistic” literature. When a genre draft is bad, however, it’s probably because the writer has been consumed by the formula. That’s an easier problem to fix.

When I tell students they can write anything as long as it’s “literary,“ I define the term as “character-driven.” Nonliterary fiction, I explain, is plot-driven and includes any story in which characters act according to the needs of the plot rather than from an artfully crafted illusion of psychologically complex motivation. Plot is still important—without it, the best you can hope for is a beautifully chiseled character study that lacks any page-turning momentum. But, I ask, is the plot serving the characters, or are the characters serving the plot?

It’s not a perfect (or particularly original) definition, but it gets the job done. When I faced down my first zombie in a workshop, I didn’t flinch. I also didn’t chuckle and dismiss the story as a warm-up. I critiqued it the same way I would critique a piece of narrative realism. And, when the student turned in a revision, the story had transformed into realism. The zombies didn’t vanish, but the characters’ genre-determined behaviors did. Alternate worlds aren’t the only stories choked with clichés, but they do have more overtly defined sets of formula expectations. And that makes them easy to gut. Just ask one question: Is the world serving the characters, or are the characters serving the world?

Davis’s zombie ban sparked some outrage from fellow writing professors, but I agree with Lesley Wheeler, who wrote in her literary blog that Davis, despite the weaknesses of his argument, “seems like a dedicated teacher who wants to do the best he can by his creative-writing students.”

I’ll go a step further. Not only do Davis and I have the same good intentions, he and I want to help our students produce exactly the same kind of story. Davis confuses it with “real environments,” but that’s a surface element. He wants depth. He wants psychological realism. It doesn’t matter if the characters are androids, elves, or mere “humans”—as long they behave humanly. Does the zombie stumble through its life in all the messy and horrific ways readers recognize from their own lives? If so, the character is “real,” whether zombified or not.

“Literary” stories require readers to infer complex inner lives for artificially real characters. I won’t deny the pleasures of formula and its plot-beholden characters, but they’re nothing compared to the joys of eating an imaginary brain. Open a skull and explore all the flavors. I demand all my students to be zombies.

[A version of this article originally appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education.]

Tags: Adam Brooke Davis, Lesley Wheeler

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

06/01/14 Real Life Justice Leagues

Wall Creeper, Shadow Hare, Dragonheart, Zetaman, the Crimson First—never heard of them? They’re self-proclaimed superheroes patrolling the streets of Denver, Cincinnati, Miami, Portland, and Atlanta. There are dozens more—Hero Man in L.A., Captain Prospect in D.C., Razorhawk in Minneapolis—with entire Leagues of such would-be Avengers: Team Justice, Black Monday Society, Rain City Superhero Movement, Superheroes Anonymous. RealLifeSuperheroes.com insists its members “are not ‘kooks in costumes,’ as they may seem at first glance.” According rlhs.org, they “seek to inform, and, most importantly, inspire” through “charity work and civic activities.”

Since these organizations, like non-costumed neighborhood watches, work within the law, they usually do no harm, and their “safety patrols” might even deter crime a bit. But they’re not superheroes. They’re self-designed cosplayers staging theatrics on city streets. They don’t actuate the superhero formula. Which is a very good thing. Otherwise they would be a league of Patrick Drums, AKA The Scorpion.

Drum doesn’t dress up in a giant scorpion costume. When police arrested him in 2012, he was wearing a white tank top and khakis. Lexi Pandell recently detailed his adventures in The Atlantic. Like the Punisher or Dexter or the 1930s Spider, Drum is dedicated to killing bad guys. Oliver Queen on season one of Arrow crossed off names from a checklist of targets he murdered; Drum only ex-ed out the first two on his list of 60 registered sex offenders living in his Washington state county (about eighty miles outside the safety patrols of Seattle’s “real life superheroes” Buster Doe, No Name, and Phoenix Jones). While RLSH members “believe in due process” and “are certainly not vigilantes,” Drum told a courtroom, “This country was founded on vigilantism.”

The list of superheroes taking inspiration from animals is longer than Clallam County’s registered pedophiles. Bruce Wayne, like Drum, needed a defining emblem before starting his war on criminals. A bat didn’t fly through Drum’s window, so he looked back to a childhood memory instead. In a note he left beside his victims’ bodies, he explained how he’d once watched scorpions in a pet shop aquarium circling “in full battle ready posture” to protect a pregnant female. “This spirit always impressed me.” He left his emblem, a scorpion encased in a lollipop, with his signed notes. After his second murder, Drum planned to go off the grid and “live in the wild,” the site of his origin story. When he was ten, a stranger got him drunk and lured him into the woods for oral sex. Like Batman, Drum is after vengeance.

“My actions were not about me,” he wrote in superheroic grandeur. “They were about my community. I suffered many failures and my overall view of things was one of hopelessness. I took that hopelessness and in turn threw myself away to a purpose. I gave myself to something bigger than myself.” And, as in so many superhero sagas, the community championed him. The county prosecutor abandoned the death penalty because she doubted she could convince a jury to execute him. Drum has too many supporters.

And what if those supporters organized a league of like-minded vigilantes? They wouldn’t look like comic book Avengers or any RLSH cosplayers. They’d look like the Klan. Detroit is currently patrolled by a RLSH cosplay team called the Michigan Protectors, but back in 30s, the city was under the watch of the Black Legion, a splinter group from the Ohio KKK. The Protectors’ Adam Besso, AKA Bee Sting, retired from superheroing in 2012 after pleading guilty to attempted assault with a weapon (his “stinger” was a shotgun). But that’s nothing to the 1936 conviction of nine Black Legion members for the kidnapping and murder of Charles Poole, an alleged wife-beater targeted by the vigilantes.

According to historian Peter H. Amann, the Black Legion’s founder, William Shepard, supplied his superhero team with secret rites and costumes: “You have to have mystery in a fraternal thing to keep it up,” he said; “the folks eat it up.” Black Legionnaires sported black hoods, pirate hats, and robes with cross-and-bones on the chest—the same emblem Exciting Comics’ superhero Black Terror would use in comic books. Despite the Black Legion’s apparent passion for “crime fighting,” in “real life,” Amann writes, their actions “were neither glamorous nor likely to reduce crime.”The Detroit News made the same conclusion: “Hooey may look like romance and adventure in the moonlight, but it always looks like hooey when you bring it out in the daylight.”

So will the world never witness a League capable of championing real Justice? Maybe not, but the virtual world already has. Terre des Hommes, an international children’s rights charity group, has introduced “a new way of policing.” Like Drum, the organization wants to target pedophiles, but instead of hunting down and killing registered convicts, this Justice League exposes unconvicted ones roaming freely on the web. From their high tech batcave, a warehouse in Amsterdamn, members of Terre des Hommes (it means “Land of People”) don the team disguise of a computer-animated Filipino child named “Sweetie.” She’s supposedly ten (same age as Drum when he was assaulted), and when predators video message with her, they have no idea Terre des Hommes is locating their real world addresses. So far the superheroic Sweetie has netted some 200,000 Internet users. A thousand of them wanted to pay her to perform sexual acts.

Terres des Hommes has swept 71 countries so far. Drum couldn’t cover a single U.S. county. I doubt many RLSH cosplayers have considered assuming the alter ego of a powerless ten-year-old to battle crime, but Sweetie is probably the only real life superhero out there. I wish her Justice League continued success.

Tags: Black Legion, Lexi Pandell, Patrick Drum, Real Life Superheroes, Sweetie, Terre des Hommes

- 4 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized