Monthly Archives: July 2019

21/07/19 A House in a Jungle in a Comic

A recluse grows addictively hallucinatory pineapples in a jungle near a small but expanding town where he sells them through an organic supermarket in order to pay a guru to transport him to the world of his visions. While that plot may sound plenty odd, it only touches the surface oddity of Nathan Gelgud’s graphic novel A House in the Jungle. There are also inexplicable bags of garbage and then dead dogs that appear on the reclusive Daniel’s property—which technically isn’t his property, a fact the ambitious would-be mayor exploits in his attempts to please an almost mythic and soon-to-visit governor. What that has to do with the privatized dump, the missing townsfolk, and the crushed insects Daniels uses to grow his pineapples are more surface mysteries worth reading for. But Gelgud’s most intriguing oddities occur at a deeper meta-level. A House in the Jungle isn’t just a story—it’s a comics story exploring the comics form that contains it.

When Daniel’s guru asks him, “Did you stick to your speech limit? Sometimes it doesn’t work if you don’t stick to your speech limit,” the character means that their attempt to induce a revelatory vision might fail if Daniel has broken his not-quite-monk-like vow of mostly silence (which is why he carries a card when he goes into town: “SORRY. I’m at capacity for today”).

But Gelgud also means the limited number of words on the actual pages of the graphic novel. There’s no narrated text, just talk balloon dialogue and a few sound effects (though he does have fun cheating by combining standards like “plop” and “thwack” with non-sound verbs like “scrub” and “place”). Gelgud works well with his speech limit (the early banter about the supposed chopped-up adult bodies in the boxes of what’s actually pineapples is both darkly funny and darkly foreshadowing), but some pages and multi-page sequences are wordless.

Gelgud enjoys dividing actions into paneled units—the five steps of writing on a chalkboard, the six steps of removing a t-shirt—which emphasizes the paradoxical physicality of his visually simplified world. Those panels are also unframed. When a character or other object is foregrounded on a white background, the gutters are unmarked. It’s just figures floating in whiteness with implied but unmarked borders that blur an increasingly surreal story world with the inherently ambiguous space of the gutters.

The effect is most pronounced when an undrawn frame edge still crops out free-floating image content—as when Gelgud’s implied camera zooms into the expanding letters on the side of a crate in a three-panel sequence: “GARBAGE,” “RBAGE,” “G.” Later, the bottom words on of a sign at the town dump are cropped in half yet still oddly intelligible. Technically the obstructed letters aren’t letters, and they’re not obstructed by anything but the same whiteness they’re printed on.

Undrawn panel edges also allow Gelgud to manipulate reading paths, sometimes using a repeating figure’s movements across a white page to lead the reader’s eye in a direction that would be confusing if the figure were framed. English-based comics readers expect panels to follow Z-paths (left to right, top to bottom, same as the prose you’re reading right now), yet some of Gelgud’s pages end in the bottom left corner—while producing no confusion or not even drawing attention to that unusual fact.

Other times Gelgud’s color designs add unframed patches of color, usually with wavy edges, to define constructed settings, especially interiors. But when Daniel is in the jungle, the vegetation expands to fill the panels, with the sharp black lines of leaves and branches serving doubly as frame lines. The effect, while subtle, establishes a formal division between the house and the jungle of the title. These aren’t just locations within a formally and stylistically unified story world—they’re two different ways of representing worlds.

Gelgud increases the tension between content and form, between what is drawn vs. how it’s drawn, through Daniel’s attempts to transcend his reality through visions. On a page during the first attempt, Gelgud’s free-floating figures create no reading path, but instead presents objects in the guru’s room, some of them repeating for no reason, for the reader’s eye to explore in any order. In the second vision, Daniel sees a diamond shape that frames his body in a kind of panel—one that evokes the rectangular norms that the graphic novel so thoroughly rejects. In the third, the guru draws a circle on his floor—which is of course also a circle, a kind of panel frame, that Gelgud draws on the white of the page. Daniel steps in and out of it with his eyes closed, again and again and again, until he finally understands: “There is no circle.” The epiphany might be a rudimentary one for someone in the actual world, but for a character inside a comic, it’s literally groundbreaking.

Most of theses effects can go unnoticed, but their accumulation shifts the nature of Gelgud’s story away from standard comics norms—not unlike the way the townsfolk are slowly altered by Daniel’s addictive and increasingly hallucinogenic jungle pineapples. The guru’s circle also expands into a visual motif when the bartender stares into the same circled whiteness while wiping away spilled beer. On his fourth visit, Daniel wears a mask, and the eyes holes create circular frames within the scribbled, rough-edged black of larger panels. The image-within-an-image echoes the larger world-within-a-world meta-context, one that visually expands when Daniel frames his entire house within a circle of white paint. Since it’s night, the background is grey, and Gelgud’s panels are for the first time rectangular with what is almost a standard gutter—only with its whiteness merging with the white of the circular paint where the panel edge meets it. Even though the two whites are of course the same white of the page background, one represents a painted line and the other represents literally nothing.

All of this formal playfulness occurs within a story about a person trying to reach another plane of existence. When Daniel’s attempted visions fail to transport him fully, he still feels something: “Like I’m not alone. Like I’m being watched.” He of course is being watched—by the reader holding the object that defines his entire physical existence in her hands. That’s a pretty cool way to explore the comics form. I would like to say that Gelgud exploits it fully, but the final pages of A House in the Jungle don’t reach the meta-potentials that the rest of the novel so artfully suggest. But the near-miss is still well-worth the close read, with the hope of more to follow. Daniel didn’t transcend his world on his first try either.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

15/07/19 Three Things That Don’t Define Conservatism

I began this as a response to a new member of Rockbridge Civil Discourse Society who wrote a very thoughtful Facebook comment about his (and Russell Kirk’s) views on conservatism. Since this grew too long for a post on the RCDS Facebook page, I’m publishing it here and linking to it.

I would like to respond to Robert’s three main points: 1) “a moral focus is the defining feature of conservatism,” 2) it is coupled with “a reverence for our nation’s founding and the philosophy behind it,” and 3) that these result in conservatives’ “adherence to meaningful tradition, their preference for small government with clearly defined powers, and their strong patriotism.”

While I accept these to be (mostly) true, I also think they are all (unintentionally) misleading. To call a feature “defining” (especially in the context of an implied contrast to anything not conservatism, and so in this case, progressivism) is to imply that the feature is distinguishing. It is to say that the feature makes the thing in question different from other things. I think this is untrue for all three claims. (For a silly example, if the general topic were pets, and someone wanted to distinguish cats from dogs, it would be odd to begin by saying “breathing oxygen is a defining feature of cats,” since it is equally true that dogs breath oxygen.)

Like conservatism, progressivism is rooted by a moral focus, revers the philosophy of our nation’s founding, and is strongly patriotic.

Robert included a pdf of a textbook chapter by Mark C. Henrie titled “Understanding Traditionalist Conservatism.” Since “conservative” and “liberal” have had multiple, evolving, and sometimes even overlapping meanings, I like the clarity of “traditionalist conservative” (which also helps to distinguishes it from libertarianism, which, while arguably conservative is not traditionalist). But I’ll use the shorter “conservative” to mean traditionalist, and between the synonyms “liberal” and “progressive” I prefer “progressive” because it also seems clearer. Progress and tradition are the defining poles. I quote Henrie:

“The traditionalist conservative’s first feeling, the intuition that constitutes his or her moral source, is the sense of loss, and hence, of nostalgia. Those who are secure in the enjoyment of their own are often progressives of a sort, so confident in the solidity of their estate that they do not shrink from experimenting with new modes and orders.”

I mostly agree. Progressives default to change and so imply that the status quo is an obstacle in the arc of moral progress. Conservatives default to tradition and so imply that the status quo is the most moral achievement possible (or at least the safest to preserve). This produces two mirrored extremes: for the progressive, resistance to change is resistance to morality, and for the conservative, resistance to tradition is resistance to morality. Both extremes are (in my opinion) hopelessly wrong, but I do think they accurately describe two main types of moral reflexes.

Progressives and conservatives can disagree about which viewpoint is correct, but—and this is my objection to Robert’s first claim—neither can define themselves as more morally focused than the other. To quote Martin Luther King, Jr. (who was quoting a Unitarian minister and abolitionist): “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” It’s the hard and profoundly necessary work of that bending that motivates progressives.

Robert’s second claim is that conservatives are defined by their reverence for American founding philosophy. Again, while this is true, it is not distinguishing because the same is equally true of progressives. Progressives believe that the moral arc extends from the words “we the people” and “all men are created equal” and that progress is the bending toward the fulfillment of those extraordinary founding principles.

Again, conservatives and progressives can disagree about which aspects of our founding documents are most profound, but neither can claim to have a greater reverence for them overall. And this extends to the last part of Robert’s third claim, that conservatives have “strong patriotism.” Progressives, through their dedication to the American principles of equality, are equally and overwhelmingly patriotic.

Robert’s third claim also referenced conservative’s “preference for small government.” While this would probably be both a defining and distinguishing feature, I’m not certain it’s true. I do not see an inherent link between preserving tradition and limiting government. Or if there is a link it is a merely historical one, not a principled one. If conservatives wish to preserve a status quo against a change that progressives are promoting through government institutions, rejecting government institutions is an effective strategy. But it is only a strategy, not a principle. If conservatives instead see government as an effective strategy to preserve a tradition, they are as likely as progressives to adopt it. This varies for both conservatives and progressives case by case. For example, many conservatives supported a constitutional amendment defining marriage as between a man and a woman. That is the opposite of limited government. The marriage between limited government and traditionalist conservatism (as opposed to libertarianism which really is distinguishable by limited government) is a marriage of convenience. As with morality and patriotism, neither conservatives nor progressives have a greater or lesser link to government, whether “big” or “limited.”

One last point. According to Henrie:

“Kirk’s ‘canons’ of conservatism began with an orientation to ‘transcendent order’ or ‘natural law’ … Kirk stated emphatically that the overarching evil of the age was ‘ideology,’ and he claimed that conservatism, properly understood, is ‘the negation of ideology.’”

In my own field of literary studies, I distrust anyone who claims to have no theoretical framework but to instead take a “neutral” or “natural” approach. There’s no such thing. But who doesn’t think their own approach is “normal” and so the norm from which all other approaches err? Probably most conservatives and progressives do too. And, according to Henrie, conservatism founder Russell Kirk definitely did. But the notion of an ideology that transcends ideology is a fallacy.

All we have then are two opposite reflexes: tradition and change. Both are morally motivated, defined by founding American values, and equally patriotic, and neither has any greater relationship to government or God. By focusing unilaterally on such things as morality, founding values, patriotism, government, and God, we obscure how definingly similar conservatives and progressives are–and how hopelessly lost our nation would be if we accepted only one of those reflexes.

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

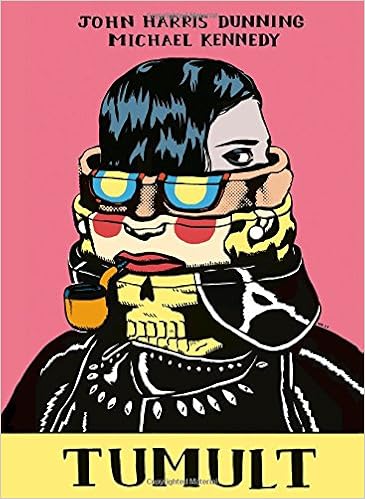

08/07/19 Tumultuous

It’s a delight to plunge into the depths of a graphic novel that so thoroughly delights in its own comics-ness. Tumult by collaborators John Harris Dunning and Michael Kennedy is on its surface a noir romp of a story with guns and killers and a leading lady who is several leading ladies—a victim of multiple personality disorder and government experiments who is both antagonist and heroine. But that surface also leads into a deep end of visual surprises infused with a surreal energy unseen except in some of the most obscure corners of Golden Age comics.

Artist Michael Kennedy’s style is hard to pin. The gritty noir context emphasizes the starkness of his lines and shapes in a way that evokes Michael Gaydos’s Jessica Jones or David Mazzucchelli’s Batman: Year One. And though his edges are sharp, there’s an internal inexactness to the oversized images that produces the tension of a camera set a degree out of focus. Kennedy also likes to center and isolate his subjects with deliberately anti-climatic framing—only to then zoom-in for abrupt and too-close close-ups of a mouth or an eye. Key moments sometimes go undrawn, throwing what should be a central event into unexpected ambiguity. Other times his frames inappropriately crop out heads, or he angles a sequence of panels from behind a speaking character, offering repeating black hair instead of shifting facial expressions. Except his faces often don’t shift but reproduce identical renderings with evolving backgrounds, emphasizing the drawn artifice of the page and its blocky layouts.

Each stylistic detail is fascinating, but the accumulative weirdness goes way deeper. The world of Tumult seems to be filtered through some obscure and obscuring process that throws its reality into uncertainty. As a viewer, you’re never quite sure where you’re standing—let alone whether its solid ground. The effect is ideal for the subject matter: a woman whose identity changes page to page with no clear, controlling center. Though the narrator is her observer, the fabric of the drawn world reflects her internal tumult. She is an incomplete weave of contradictory memories and blackouts, captured in Kennedy’s off-angles and odd cuts and other roaming peculiarities.

But the weirdness goes even deeper still. Yes, there’s a conspiracy plot and government scientists and even a transcendent spiritual hallucination, but those multiple personalities are also meta-types from early 20th century comics. When they chat with each other, we’re dropped into a literally tarnished, benday dot-colored world of newspaper comic strips. Even the narrator’s world, the baseline reality of the novel, has more to do with the 1930s than the 2010s or the 1990s action film references that litter the dialogue.

Kennedy’s biggest and most unexpected influence seems to be Fletcher Hanks, AKA Barclay Flagg, a profoundly obscure comics creator who, for his less-than-two-year Golden Age career, produced the unlikely likes of Stardust the Super Wizard and Fantomah, Mystery Woman of the Jungle. Rightly forgotten for decades, Hanks re-premiered in the ground-breaking anthology Raw in the 1980s where his incomprehensible incompetence was reinterpreted and embraced for its accidental surrealist effects. Editor Greg Sadowski writes in his Supermen! The First Wave of Comic Book Superheroes 1936-1941: “Hanks’ singular, obsessive—and at times unintentionally hilarious—approach found a fortuitous opening in comics’ formative period; his work would have been unthinkable only a year or two later.”

To be clear, in terms of skill and intent Kennedy’s artwork is the opposite of Hanks’. Kennedy is making carefully crafted choices for dizzying effects. He’s just selecting those effects from the idiosyncratic chaos of Hanks’ naively drawn pages. There’s also the possibility—since Tumult’s PR and surrounding matter never mention Hanks—that I’ve projected influence where there’s only coincidental (albeit unnerving) resemblance. Regardless, Tumult is artistically ingenious.

Instead of Hanks, the back-cover blurb evokes Alfred Hitchcock and Patricia Highsmith—a legendary film director and a noir novelist best known for her Ripley series about a psychopathic anti-hero. While both references are apt, they point away from the novel’s most interesting qualities because they point away from the comics form. Tumult is not simply a narrative that happens to have been developed graphically and so might still translate into film or prose. It is so fundamentally a comic that talking about its plot and characters without their visual grounding literally and metaphorically misses the picture.

This isn’t the case with many graphic novels. Some comics stories work the comics form like storyboards of documentary-like events set in a fictional world. The artist gives a certain stylistic spin to the content, but if the comic were to change artists mid-story—a norm of so many mainstream series—the story isn’t fundamentally affected. But Tumult without Kennedy’s defining style would not be Tumult.

Taken as just a narrative—presumably the narrative that Dunning wrote in script form and handed to Kennedy to illustrate—Tumult is a perfectly good retro-thriller. While unsympathetically dickish, its primary narrator Adam is no talented Mr. Ripley or hard-boiled avenger policing a moral wasteland. He’s just a second-rate film director sabotaging his life because he doesn’t have what it takes to be a main character. So when the femme fatale finally enters on page 46, she’s not only his life line but the story’s too.

Though Adam longs to be her noir savior, he recedes into the plot’s margins as Morgan and her multiples rightfully claim center stage and the dramatic action. It turns out Adam literally is just a supporting character. That’s an intriguing meta-fact, but neither the character nor the story seems aware of it, dropping the elaborate first act into retroactive limbo. If Adam’s actions, including his motivated point-of-view on Morgan, don’t unlock some key plot or personality element, then what’s the pay-off for our having watched him cheat with a teenager to dump his girlfriend of ten years and then squander his single shot at a major movie deal because he’s too busy binge drinking? Not only he but his entire character arc recedes, and so then Morgan’s story might have been observed from just about anyone’s perspective, not just this particular nobody’s.

But the artfulness of Tumult isn’t Kennedy’s alone. Dunning’s Adam offers more than one killer description (“Like a spaghetti western set, I looked okay from a distance”), and I presume it’s Dunning’s script that mapped any of a range of visual motifs that Kennedy executed. I especially admire the fantasized close-ups of the teenager’s foot stepping on Adam’s fingers as they grip a cliff edge. The initiating sequence runs parallel to but is unexplained by Adam’s panic-driven narration, leaving the viewer to decode the visual metaphor and how, even though the event never actually happened, it kinda did.

I could go on, but these visual pleasures are best experienced first-hand. Tumult is also this dynamic duo’s first adventure together. I will be startled if it’s their last.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

[Also, here’s an email conversation I had with the author:

Mon 10/8/2018

I’m Michael Kennedy, the artist on Tumult, a graphic novel you recently reviewed for the Pop Matters website. I’m writing with positive thoughts about your analysis of the book and my work in particular as you touched on a couple of things that haven’t been noticed by other reviewers! And when I read your author profile as a scholar of comics and literature I was no longer surprised.

Firstly I appreciate the comments on the panel choices, only one other scholar has asked me about the choice to ‘zoom’ in on certain things, the script did contain a few visual directions like that and it then became a stronger part of the adaption into art. For me I’m a big fan of heightened emotion and melodrama, although a large fear I had was storyboard comparisons. I feel as though it comes from instinct and a level of primivitism in storytelling that I’m fond of.

That leads to the Fletcher Hanks influence which there was an fair amount of, however the true influence comes from horror comics of the 1950s (of the non E.C variety, found in “four colour fear” a Fantagraphics collected book) so I was indeed setting out to make a comic.

This all stems from John’s script again, as the Ben day cymk type scenes were in the script, with the hotel sequences deriving from strips like “little lulu” and the graveyard scene derived from Frank King and some of his more experimentally drawn strips in “Gasoline Alley.”

Anyways I really just wanted to reach out and show my appreciation for your article. I imagine John feels the same way.

All the best

Michael Kennedy

*

What a pleasure to get your note. And, frankly, I’m relieved that I didn’t completely invent the Fletcher Hanks influence! I know some EC, but not Four Color Fear–but I still sense that 50s horror vibe generally. And I probably should have tracked down the specifics on Little Lulu and Gasoline Alley. It really is a remarkable book you and John made, that great balance of accessible but still idiosyncratically weird. Are you working on anything new right now?

Chris

I’m glad you enjoyed me reaching out, I think the little lulu and frank king refs were only subliminal influences but a Easter egg for some nonetheless. We’re currently working on some pitches for the American mainstream, monthly comics, African science fiction, some alien abductions, (all top secret obviously haha).

Tags: John Harris Dunning, Michael Kennedy, Tumult

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized