Monthly Archives: June 2021

28/06/21 Medium, Technique & Style: Eight Heads

Nesting dolls might be a good metaphor, with medium as the largest outer container, which twists open to reveal technique, which twists open to reveal the tiny center doll of style.

My medium is, as usual, MS Paint. Though officially “deprecated” since 2017, the doddering grandparent of graphics software remains my preference in part because post-Photoshop tech intimidates me, but also because limitations are paradoxically freeing. I use no pre-set or built-in effects. It’s all idiosyncratic invention.

The resulting technique is hard to describe, but it leans heavily on the “Transparent selection” button. I tend to start by scribbling an embarrassingly simplistic sketch of facial features using the touchpad on my laptop on the thinnest “pencil” setting. Next I copy and past layers and layers and layers until the original lines get lost and the image grows thicker and soft edged. I use that new conglomerate image as a filter over itself, creating multiple partial versions, that I then recombine in new layers. Final steps vary, but there’s a lot of scissoring out sections and rearranging pieces, usually with overlapping edges.

Style is even harder to define. I’m told the effect is charcoal-like, but that may have more to do with the oddity of the technique. I also suspect that someone else following the same steps would produce images that look different from these. The style is also emergent, meaning I don’t know what things are going to look like until they start looking like something that I didn’t exactly plan. Someone else might not-plan something that ended up evolving very differently.

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

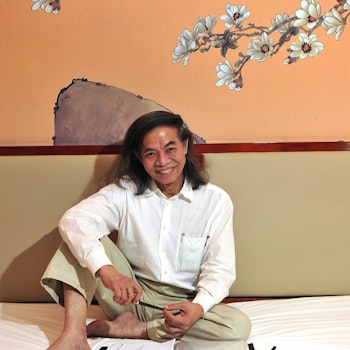

21/06/21 Ronald Reagan’s Favorite Philosopher

Chih-chung Tsai, a renown cartoonist in Asia, publishes as C. C. Tsai in English. Dao De Jing, which translates roughly as “The Way of Virtue,” is his fourth in a continuing series of Chinese philosophy adaptions, in collaboration with translator Brian Bruya. While the best known of the selected philosophers to English-speaking readers is likely Confucius, Laozi may be equally influential and, according to legend, briefly taught Confucius. Bruya in his introduction acknowledges that Laozi may never have existed and that his famed book may have been written by multiple authors compiled over many years—and yet Dao De Jing’s insights still endure.

A possibly non-existent main character also provides Tsai the greatest freedom of interpretation. His cartoon Laozi features a head roughly a third the size of his entire body. His chin merges with his neck in a single pen stroke, and his mouth is seemingly obscured by a comb-like mustache draped from his oval of a nose. His enormous curving ears are his largest features, extending almost to the top of his flat head.

While it’s odd to read the talk-balloon musings of a Yoda-proportioned philosopher, the juxtaposition provides a humorous undercurrent to the esoteric philosophy. Would the would-be Laozi approve of his words being mouthed by a cartoon version of himself? Based on Bruya, who praises the original work for its “catchy and superficially appealing” style, I suspect he would. I certainly do. Still, Little Laozi (he’s not named that, but there should be some way to differentiate the historical character from Tsai’s rendering) alters Laozi’s words just by appearing to utter them.

Tsai applies the same cartooning norms to the philosopher’s surroundings. While likely uninfluenced by him, Tsai’s carefully curving and angled shapes are reminiscent of Al Hirschfeld’s hyper-stylized caricatures popular in the U.S. in the 1970s. Tsai’s sharp clean lines form similarly exaggerated and simplified figures. No crosshatching suggests depth or texture, so the interior spaces of most bodies are as empty as the interior panel space surrounding them. As it adapts aphorism about simplicity and balance, the style resonates well beyond its surface.

That style as well as the book’s layout approach are identical to Tsai’s The Way of Nature, an adaptation of Zhuangzi also published by Princeton University Press in 2019. I admit that at first glance, I was disappointed that Dao De Jing could easily be mistaken for the earlier work. But that’s a little like complaining that Shakespeare wrote only Shakespearean sonnets. When you innovate your own effective form, why alter it?

Tsai’s layout remains elegant. Built around consistent two-page spreads, each left-hand page opens with a full-height caption box containing Laozi’s original Chinese text inside double frames, and each right-hand page closes with the same. The side caption boxes never vary in size, but the amount of writing does, with as many as five columns of ideographs and as little as one, and always with copious white space unused. The side boxes also visually highlight where Tsai steps beyond his philosopher’s text. The opening of Tsai’s adaptation features six pages with empty side boxes—meaning the content, a brief biographical introduction to Laozi, is all Tsai.

I can’t read Chinese, but I appreciate the general translation principle of providing originals and, even better, how well Tsai integrates them with the translated content sandwiched between. Tsai uses the columns as a visual element, with the lines that compose the ideographs echoed in the cartoon sections between them. Gutters separate the caption boxes, but adjacent frames are interconnected with single lines defining each set of panels. It’s a subtle effect, but the choice compresses the multiple panels into a single ideograph-like page unit. The interiors of the panel are sparse, with the English text floating freely in negative space that merges with the mostly undrawn backgrounds of the cartoons. The thick black lines of the drawings, the English words, the frames, and the ideographs all combine in balanced compositions well-suited to the themes of Laozi’s writings. Such sage observations as “The idea cannot be clearly explained through language” takes on additional meaning. Tsai also creates a visual rhythm with Laozi often speaking the final, moral-like statement in the white space of an unframed final panel.

Bruya’s introduction is especially targeted at American readers who, he warns, tend to read Laozi through a Reagan-eque, libertarian lens. Reagan, Bruya notes, quoted the Dao De Jing when arguing for smaller government. Bruya’s translation of Chapter 60 is less pithy than the one coopted by Reagan’s speech-writer (“Govern a great nation as you would cook a small fish; do not overdo it”), but I suspect it’s more accurate: “Governing a large country is like frying a small fish—you can’t turn it over too often.” And to Bruya’s credit, he encourages readers to seek out many translations to study their “different perspectives and explanations.”

Still, his warning seems key. Reading Chapter 57’s “The more laws there are, the more outlaws there will be” in isolation destroys the balancing principle at the heart of Laozi’s teachings. The goal is not less government, but less self—a concept harder to cut and paste into a GOP political speech. Laozi instead concludes his book with an aphorism well-known even during his lifetime, “To give is better than to receive,” because it encapsulates the “non-contentious spirit” of sages, as well as “the spirit of the dao.”

Tags: Dao De Jing

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

14/06/21 Let’s try to talk about The 1619 Project

I co-created Rockbridge Civil Discourse Society in 2017 and moderated the Facebook page until exiting last August. I’ve since returned, but no longer try to moderate. The following week-long conversation is taken verbatim from a comment thread branching from Robert Cook’s very accurate observation that the page had descended into “notifications reflecting insults, ad hominem, dismissing arguments instead of addressing them, and teaming into camps to oppose different perspectives. I’ve wanted to engage in this conversation–as an educator in a school district where CRT and the 1619 project is at the center of debate–but the environment on this page has not been conducive to conversation, but rather partisan politics and mud-slinging… Given the ideological diversity of RCDS, we need to consider how our interactions on this platform relate back to depolarization. I think Lincoln’s remarks on the Temperance movement in his Temperance address (attached below) speak volumes to this. If we truly are seeking understanding and depolarization, then we need to be sincere about it.”

AARON: Thanks for the reminder. I appreciate your Lincoln quotes. I would encourage everyone here to read our friend Dr. Lucas Moral’s “Lincoln and the Founding” if they are interested in understanding what Lincoln might have thought about “1619”.

CHRIS: Aaron, I’ve not read Lucas’ essay, and I also haven’t read any of the 1619 Project essays either. Have you read any of them?

AARON: I’ve read his essay and his book, “Lincoln and the Founding” (although he doesn’t specifically name “1619” in the book but the entire subject addresses Lincoln’s unwavering believe in the idea that America was founded on principles of liberty in the “spirit of ’76” and that the Fathers foresaw the eventual death of slavery. I have read excerpts from the 1619 essays but have not read them in entirely. I fully reject the premise of their foundational argument that America’s “true” founding was with the first trans Atlantic slave ship.

CHRIS: Since you express strong feelings against the 1619 Project, I think you are intellectually obligated to read at least one of the essays in its entirety and not rely on someone else’s summary and selections. I say that with no expectation that reading an entire essay will alter your opinion and I suspect you will find more to object to. But I don’t think you currently have an opinion–you have someone else’s opinion. I get tired of hearing the Project repeatedly mentioned as a GOP talking point from people who haven’t read any of it. I’m also saying this to you because I think you are one of the few conservatives on this page who would actually care enough to read it and so have the basis for formulating a legitimate opinion.

AARON: I saw that one coming. it’s a fair point. I’ve downloaded it and will accept your challenge. I’m on vacation this week and should have time to thoroughly digest it. In return, I’d ask that you at least read this Wiki on it and keep an honest open mind when reading the criticism. I’d also once again encourage Lucas’ book as he is a Lincoln expert. It’s a short read, maybe 5 hrs.

CHRIS: Aaron, I’m out of town right now too, so no worries. How about you select one essay from the Project, and we both read it? I think Lucas’ essay is a response to one specific essay, so that might be a good choice?

CHRIS: “One crucial “1619” installment is a 7,300-word essay by Nikole Hannah-Jones titled “Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals were False When They Were Written. Black Americans have Fought to Make Them True.”

AARON: I read “our founding ideals were false”. My copy didn’t have footnotes with references so I am taking everything she quoted from our founders as being truthful. Let me know when you want to discuss.

CHRIS: I’m about half way through. Happy to discuss at any time.

AARON: So, I’ve thought a lot about how to articulate my opinion on this essay. As you know, Facebook is a great platform for quick and pithy responses. Cleary, this is going to require more in-depth critique- especially if I’m going to portray my sincere desire to be a productive member of our society actually trying to mend the race relations. Not being an academic, I’m sure I won’t be nearly as disciplined in my line of thought as many on this page.

Firstly, I want to agree with Hanna-Jones when she says that the plight for liberty of Black’s in America is *very* much an integral piece of our “Great Experiment”. With 6,000 years of recorded history, the last 250 years of the attempt “self-government” and fundamental basic rights in USA has been an awesome advancement of human political structure. Watching America grown in it’s understanding of personal liberty is a fun experience.

Other than that, I fundamentally disagree with most everything else she presents; primarily, her narrative. When reading the essay, I was reminded of Obama’s pastor, Jeremiah Wright saying, “God Damn America” in a “sermon”. Apparently along the way of him “shepherding” his congregation, he expressed the belief that the American government developed the AIDS virus to control the black population. It’s no wonder that folks like Hanna-Jones write essays with this narrative if they’ve been sitting in the pews of someone continuing to preach these types of storylines (I have no idea if she has heard Wright’s sermons but assume that he’s not the only pastor with these kinds of storylines).

I was desperately hoping to see her end her essay by finally understanding why her father flew the American flag and that she now see’s hope that the “Stars and Stripes” symbolize the attempt for people that “even look like her” to chase after liberty and justice for all. In my opinion, *that* would have at least brought some sense that she was attempting to be a positive energy in trying to make America better. Instead, she leaves us (and now presumably our public-school children since this is going to be taught in schools) with the impression that she still thinks her father was a fool for flying the American flag. Instead, she came off as only trying to tear us apart.

I need to go right now and realize that I haven’t actually presented any official counter argument. I don’t expect you to respond to this because as of right now, it’s only my “emotional” experience to reading it. I fully expect you to have had a vastly different take.

I’ll try to formulate my best line of attack on her factual misunderstandings of our founding and *why* her narrative is false as soon as I can.

AARON: Let me make one more post to help put into context why my antenna are raised with 1619/Critical Theory/BLM and help frame my ideas as to why I’m suspicious of ulterior motives. I remember when Michelle Obama was stumping for her husband and made a couple of surprising claims. The first was the quote, “For the first time in my adult life, I’m proud of my country.” That’s an astonishing claim. Nobody claims that America is without sin but to take it to that extreme made me scratch my head. Then, even more interesting to me was her statement of, “Barack knows that we must fundamentally change America.” (Barack doubled down on the commitment when he said this, “We are five days away from fundamentally transforming the United States of America.” — Barack Obama, October 30, 2008). Things become more sharply focused when one realizes that those quotes came from 2 people that let the G.d D..n America “Reverend” be their spiritual mentor for 20 years.

I’ve mentioned several times in RCDS of my interaction with the young college grad who pulled the ad hominine attack on the Constitution with the argument a) Founders had slaves so, b) Founders were immoral, c) Founders wrote the Constitution so, d) Constitution is immoral. A few years later and I am witnessing statues of our Founders being toppled.

When I put all this together, I start to wonder if there is a coordinated attack on our fundamental ideals of a free society with limited government and equal protection – especially when I read that public schools are planning to teach the children, “Our Founding Ideals of Liberty and Equality Were False When They Were Written”. The attack, I fear, is based on the desire for collectivism and the need for redistribution. The pesky Constitution puts major road blocks on the government’s power to take property from one person and give it to another simply because some people have been blessed with more than others. I’m afraid the desire to erode the Constitution is a real threat and I bow up when I hear, “It’s a living and breathing document.”

One might argue, “but the white guy got rich off the backs of the black guy 250 years ago”…it’s a fair point but, as I’ll argue later, our founding ideals and Constitution with it’s concept of Federalism and check/balances do make the wheels of justice grind slowly but are designed to keep history’s biggest monster, Despotism, from rearing his ugly head. In my opinion, the answer for sins that happened 250 years ago is for a blind Lady Justice *today*. Giving the power of redistribution to the government is opening Pandora’s box that *will* eventually destroy “Liberty and Justice for all”. As you’ve heard me say before, what happens in a democracy when the *majority* decide it’s time for some “redistribution” into *their* bank accounts?

AARON: So, here’s my first attack on the actual essay itself. Again, I’m sure I won’t be as disciplined with my line of argument as you Phd’s but hopefully I will establish my positions albeit somewhat clumsily.

First, I think we need to put 1776 Americas into context when it comes to slavery. If you will excuse the crude metaphor, I think that the colonies were not unlike a prostitute addicted to the crack her pimp got her hooked on. Europe force fed the slave trade to the Americas as they benefited from it and very soon after our Independence from England, we began our difficult “de-tox” of eradicating it from our new nation – Our new nation that began in 1776, *not* 1619. The new “America Experiment” of a “more perfect union” that was beginning its journey of liberating man from despotism.

Let me roll out a time table for us to put things into context. 6,000 years of repeated kingdoms of tyranny in human history (admittedly with sprinkles of liberal thought) and along comes the 18th century “classic” liberalism. The colonies had slavery for 120 years before becoming a new nation- starting in 1655 (ironically the first slave in America was actually *owned* by an African American- Anthony Johnson) to our Declaration of Independence.

1776- Declare Independence

1783- War ends- America as we know it begins to be able to focus on it’s actual identity as it’s no longer all consumed with the war effort.

1787 – N.W. Ordinance prohibits slavery in the only territory the federal government owned. That’s only 4 years after the war.

1789- Our Constitution was Ratified

1808 – President Thomas Jefferson signs into law the ban on *all* importation of slaves. That’s the author of our Declaration and major contributor to our Constitution signing the law only 19 years after our Constitution was ratified. As a perspective, Bill Clinton’s term with Monica Lewinski to today’s “me too” movement has been 26 years. 19 years is *not* a long time for laws to evolve.

When Jefferson wrote our Declaration of Independence, he was not proclaiming that in the new nation’s current state, all men were going to immediately or currently enjoy the liberties he was espousing. The Declaration was setting the course for the underlying principles that the new nation would begin to govern under and confer upon its people as soon as circumstances permit. As a side note, Jefferson’s original draft of the Declaration condemned the King for, “prostituting his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce determining to keep open a market where men should be bought and sold.”

Ironically, our founding ideals of limited government with its checks and balances and concept of federalism did in fact slow the process of eradication of slavery as our founders were committed to giving the independent states a healthy voice in the laws of the land and refused to give the Executive the power to dictate by fiat.

****Hanna-Jones’s claim that protecting the institution of slavery was an impetus for the revolution is poppycock****

CHRIS: Aaron, tons of smart things to respond to here, but let me start with your big picture claim: there is a coordinated attack on our fundamental ideals of a free society with limited government and equal protection based on the desire for collectivism and the need for redistribution. And Hanna-Jones’ essay gives ulterior support to that ultimate goal.

I can’t read Hanna-Jones’ mind, just her words, but I can (mostly) know my own mind, and I know that I don’t share any such desire or am participating in any such attack. And to the degree that I can know the minds of the many many progressive friends and family members I know and have known over the decades, they don’t either. I think you’re being mislead into believing progressives want to “take property from one person and give it to another” (and my support for raising taxes by a couple of percentage points on the highest tax brackets is NOT that, especially given how tiny that increase would be in contrast to taxes from the 1950s to the early 1980s).

But I do agree with your assessment that this argument is nonsense: “a) Founders had slaves so, b) Founders were immoral, c) Founders wrote the Constitution so, d) Constitution is immoral.” But people like Hannah-Jones are NOT making that argument. I would normally just dismiss that as a strawman, but from your comments I see that you are being sincere. You think that is Hannah-Jones’ secret point and so you are arguing against it even though she doesn’t state it.

CHRIS: What’s surprising to me though is how much you and Hannah-Jones AGREE and yet you don’t seem to recognize that. I think the essay supports your claim: “our founding ideals and Constitution with its concept of Federalism and check/balances do make the wheels of justice grind slowly but are designed to keep history’s biggest monster, Despotism, from rearing his ugly head.”

She starts by admitting she didn’t understand her father’s overt patriotism but now she does. The essay embraces the ideals of the founding documents. “Black Americans have also been, and continue to be, foundational to the idea of American freedom. More than any other group in this country’s history, we have served, generation after generation, in an overlooked but vital role: It is we who have been the perfecters of this democracy… Without the idealistic, strenuous and patriotic efforts of black Americans, our democracy today would most likely look very different — it might not be a democracy at all.”

That compliments what you say here: “When Jefferson wrote our Declaration of Independence, he was not proclaiming that in the new nation’s current state, all men were going to immediately or currently enjoy the liberties he was espousing. The Declaration was setting the course for the underlying principles that the new nation would begin to govern under and confer upon its people as soon as circumstances permit.”

She also isn’t eliminating parts of our history but adding to it the parts that have been too ignored. She writes: “the year 1619 is as important to the American story as 1776. That black Americans, as much as those men cast in alabaster in the nation’s capital, are this nation’s true ‘founding fathers.’ And that no people has a greater claim to that flag than us.”

So while now agreeing with her father’s patriotism and reverence for the flag, she recognizes that it’s focused on the ideals of our country, and not on the flawed human beings who wrote the actual words. She writes: “The United States is a nation founded on both an ideal and a lie.” She, like you, embraces the “ideal.” But unlike you, she rejects the lie that our founders should be deified and that love of our country and its ideals must be linked to a love and respect for them as our heroes.

She writes: “Our founding fathers may not have actually believed in the ideals they espoused, but black people did… For generations, we have believed in this country with a faith it did not deserve. Black people have seen the worst of America, yet, somehow, we still believe in its best.” They persevered through the monstrous despotism of slavery and Jim Crow by believing in the ideals of the founding documents and that because of them the wheels of justice were grinding forward.

You and Hannah-Jones agree about much more than you disagree.

CHRIS: I think it comes down to this: you think toppling statues of the American founders (metaphorically and literally) is a step in toppling America and its ideals. Hannah-Jones (and I) think recognizing the undeniable fact that the founders were white supremacists (they consciously believed in the innate inferiority of black people, regardless of whether they also believed that inferiority should allow slavery) is another step in the long grinding process of actualizing our American ideals. Worse, I think (and I say this respectfully and even lovingly) your misreading of Hannah-Jones and others makes you an impediment to the ideals that you so sincerely do believe in. Hannah-Jones wouldn’t have written that essay attacking the founders if the founders weren’t falsely deified. You think her attacks are divisive. I think your false reverence is.

CHRIS: But I think likening our slave-owning founders to “a prostitute addicted to the crack her pimp got her hooked on” is a good start. Sadly, they suffered that addiction long after the pimp got himself off it (England abolished slavery in 1833).

AARON: Chris, she makes the case that, “this country was founded as a slaveocracy not a democracy”. Her narrative is a lie. It’s false narratives like this that have gotten us to the point of the psychiatrist “fanaticizing about killing all white people”. I have never “deified” our founders. I recognize their sins. They are the same sins that allowed the first slave *holder* in America to be a *black* man. They are the same sins that had the African tribes “round up” the other Africans to sell them to the traders (often to the mid-east Muslim) These are *not* sins unique to “the white guy”. This is simply a false history. 81 years after our Constitution was ratified, a black man could vote. Most likely someone was born before the Constitution was written and eventually cast a vote. Comparing the Colonies to England in the ease of which they got rid of Slavery is comparing apples to oranges. Our entire economic commerce was in need of complete overhaul in the South. Our system of governance of checks and balances and federalism compared to a monarchy makes substantial differences in this story.

CHRIS: Aaron, I agree “These are *not* sins unique to “the white guy”. But who is suggesting they are? I’m not, and neither does Hannah-Jones in the essay.

AARON: Then why no mention of the first American Slave *owner* being black? Wouldn’t that have been a great way to make sure the reader doesn’t assume she’s only attacking the white guy?

CHRIS: Yeah, I agree. An essay that welcomed white guys in by being careful of their feelings of being attacked would almost certainly be more persuasive.

CHRIS: I don’t know what exactly a “slaveocracy” is, but I think the invented word usefully points out the problem with calling a nation where so many of its members are enslaved a “democracy.” That word means: “a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.” The significance of “or” is massive in this case. The US certainly has grown into an actual democracy, but I think it’s more than fair to point out that “we the people” originally meant something closer to just white, property-owning men. I take “slaveocracy” to mean something like “a democracy with slavery.” Since slavery is one of the very worst examples of the monster of despotism, I think it’s also fair to combine the two words to illustrate how they and so our early nation was contradictory. Saying that “81 years after our Constitution was ratified, a black man could vote” is also saying that for 81 years no black man could vote. And of course voting was the least of the rights black people were horrifically deprived of during those decades.

CHARLES: Aaron, well said and supported, thanks

DAVID: Aaron, I’m appreciating following your and Chris’s conversation, but a quick note here. The Clinton-Lewinsky affair should not be considered the driver for the Me Too movement.

The focus of Me Too is on non-consensual (particularly including forcible) sexual behavior. What happened between Bill and Monica was an affair, but the sexual behavior was consensual. The driver instead was the experiences that virtually every (if not every) woman has had throughout their lives. You could maybe point to Ronan Farrow’s investigative reporting of Harvey Weinstein in 2017, if you want a more specific event.

CHRIS: Aaron, let my try this again:

Slavery is immoral. Slave-holding is immoral. The founders were slave-holders. So to the degree that the founders were practicing something immoral, they were themselves immoral. And they were still immoral even if they can be shown to have been less immoral than others in their time period.

The founders also wrote our founding documents which express some powerfully important ideals that Hannah-Jones overtly embraces in her essay. Are those ideals tainted by the personal immorality of the founders? Not if we divide the founders from those documents and so those documents’ ideals.

But if you believe that toppling a statue (which I don’t support) is the same as or part of toppling the ideals of the founding documents, then you are not dividing the two. You seem instead to see them as inextricably connected.

I (and I think Hannah-Jones) would like to divide them–because not dividing them incorporates the monstrous despotism that our founders explicitly participated in, which then DOES taint our founding documents as horrifically hypocritical. The only escape from that destructive hypocrisy is to divide the documents from the people who wrote them.

The founders were white supremacists. The US was a white supremacist nation for many many decades. Those facts are profoundly unpleasant but also vital to acknowledge. Hannah-Jones wouldn’t have written her essay if they were commonly accepted facts. When they are commonly accepted, her essay and the rest the 1619 Project will fade into obscurity because they will no longer serve a function.

ROBERT: Chris, speaking to the Hypocrisy point in your response here, Steven Douglas and Lincoln had a debate over whether the Declaration of Independence was Hypocritical or not. Douglass argued that if the founders intended to include African Americans in the all are created equal statement, then the founders were hypocritical. Lincoln disagreed here, and acknowledged that while the founders were slave owners, they were thinking ahead towards eventual abolition (this argument is carried throughout Lincoln’s speeches even to the cooper union speech that I referred to in this post). His argument in the debate is supplemented by his speech on the Dred Scott decision–that the founders were forward thinking, knowing that while they themselves were not perfectly enacting the founding ideals they were charting the course for their enduring pursuit to ensure them. I recommend looking at these pieces. The hypocrisy argument was used to justify slavery. Either they were visionaries looking beyond their generation–as Lucas Morel, Aaron Bruce, and myself would argue–or they did not intend to include all when they said “all are created equal” as Douglass asserted.

CHRIS: Hi Robert. To be honest, I don’t particularly care if the founders were personally hypocritical or not. While it might be an interesting historical question, their personal traits are ultimately irrelevant when evaluating the worth of the documents they wrote. So neither Douglass’ nor Lincoln’s interpretations matter much. The founders could personally be hypocrites, visionaries, and/or other things, but that doesn’t determine anything about the ideals expressed in the founding documents. To argue in defense of slavery by saying that the founders were hypocrites is to see the documents and the founders as essentially the same thing—which is exactly the opposite of my point, and I think Hannah-Jones’. Have you read her essay?

CHRIS: Robert, your point about the founders’ visionary foresight and Aaron’s parallel focus on the history of slavery in the US seem to be making the argument that our founding documents (meaning the ideals expressed in them) ended slavery in the US—not immediately, but eventually and relatively quickly. And yet slavery ended in the UK in 1833 without the aid of those founding documents, while 4,000,000 Americans remained enslaved at the start of our Civil War. Though, yes, there are definitely very “substantial differences” between the two countries and their histories of slavery, “our founding ideals and Constitution” did overwhelmingly fail to keep “history’s biggest monster, Despotism from rearing his ugly head” for those 4,000,000 Americans and so for America as a whole. The ugly head of slavery was then replaced by the ugly head of Jim Crow for another century.

Despite that, you, Aaron, Lucas, and Hannah-Jones agree about the extreme importance of those founding ideals.

CHRIS: Hannah-Jones concludes her essay:

“I wish, now, that I could go back to the younger me and tell her that her people’s ancestry started here, on these lands, and to boldly, proudly, draw the stars and those stripes of the American flag.

“We were told once, by virtue of our bondage, that we could never be American. But it was by virtue of our bondage that we became the most American of all.”

This is a woman who expresses profound love of her country and the ideals embodied in its flag.

AARON: David, tell that to Matt Lauer.

DAVID: Aaron, Matt Lauer (apparently) engaged in sexual assault. I don’t think that in any supports your conjecture that a presidential affair from decades ago was the driver for the Me Too movement focused non-consensual sexual behavior.

AARON: I’m pretty sure that it was consensual with an assistant…but whatever. Let’s not hijack the conversation. The point is that 19 years is a very small time in the development of civil laws.

DAVID: Aaron, you are again mistaken that the Clinton-Lewinsky affair was related to the Me Too movement focused on assault and other non-consensual sexual behavior. I’m not sure why you want to insist that they are related, and Lauer having affairs in addition to being a sexual assault perpetrator doesn’t change the focus the movement. Yeah, I don’t think it is a big deal, either, and I am interested in the main conversation here continuing and in hearing your responses to Chris, but I do think we should be accurate when talking about a movement like Me Too.

CHRIS: (MeToo started in 2006, but didn’t become known until used as a twitter hashtag in 20017 in response to the Harvey Weinstein scandal. The movement addresses both sexual assault and sexual harassment—so had it existed in the 1990s, I assume today’s members of MeToo would have understood the massive power difference between the President of the US and an intern to fit under the category of harassment even though the 22-year-old Lewinsky was consenting while having sex with her 50-year-old boss. Matt Lauer was fired over allegations of sexual harassment in 2017, and then afterwards he was also accused of sexual assault. Which means I agree with you both: no, a presidential affair from decades ago was not the driver for the Me Too movement; however, it is unclear that Aaron was actually insinuating that idea when he said: “Bill Clinton’s term with Monica Lewinski to today’s “me too” movement has been 26 years.” Can we keep talking about Hannah-Jones now?)

CHRIS: Aaron and Robert, are we done discussing Hannah-Jones? Or Lucas’s response to her essay? For what it’s worth, Aaron, I think your (and Lucas’s) objection to her claim about slavery is fair: “Hanna-Jones’s claim that protecting the institution of slavery was an impetus for the revolution is poppycock.”

AARON: I suppose that I am finished…I was going to spend some more time with the line of argument about our checks and balances with federalism compared to late 18th century European governments to help explain why it might have taken longer in America to eradicate slavery other than the easy out of “our founders were more racist than Europeans.” I just read a quote from a n.y. times contributor about how she’s triggered by too many American flags…if Hannah-Jones meant to send the message that it’s ok for her to embrace the flag like her dad did, some people aren’t getting the message.

CHRIS: I guess I just don’t really understand why it matters to you or anyone else whether or not our founders were or were not “more racist”? They were racist–almost certainly less than some and more than others. So what? That fact is not relevant unless you make it relevant. I acknowledge it and move on, happy to embrace MLK’s view that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” That bending is at least partly enabled by the ideals expressed in our founding documents. That’s fantastic and should be celebrated. So what do statues matter? They have literally nothing to do with embracing ideals. Clearly your emotional reaction to the essay (which you were smart to acknowledge in your very first comment) is evidence that some people aren’t getting her message that it’s more than okay for her and other black Americans to embrace the flag. I don’t really understand why that message isn’t getting through–because based on the passages I quoted (and which are highlighted at both the opening and closing passages), the message is overt. Maybe that’s actually the most important thing to discuss?

AARON: It matters because we want to see our nation *healed*. The false narrative that our nation was “founded on a lie” is creating *more* division. Conservatives don’t “deify” the Founders, we simply put them on their pedestal as inspiration because of their ideals that encourage to live by that standard. The vandalism of statues matter because we now have a significant number of citizenry that have been falsely taught that the systems that they have created are inherently unjust. I’m surprised that the symbolism of tearing down Thomas Jefferson’s statue is escaping you.

Yes, there are a few quotes of Hanna-Jones in the essay that give lip service to a halfhearted love of country but the general theme is embodied in this quote, “Our founding Fathers may not have actually believed in the ideals they espoused.” Chris- that does nothing to heal our nation. Two-fold- 1) it’s a false narrative, 2) even if it *were* true, the coach in me would say, “so what, quit worrying about the past and grab life by the horns *today*.”

She spoke of education in the essay and how poor whites were not educated either…that’d be “my” family tree (I certainly don’t come from rich plantation owner heritage). So what!?!? Me being jealous because someone else’s grandparents had a better education than mine does nothing to inspire me to continue pursuing excellence- it just makes me want to feel sorry for my lot in life.

Falsely pushing the idea that the system is rigged does a couple things- 1) keeps the black guy in a state of perpetual discouragement, 2) Keeps the black guy forever dependent on the handouts of Big Brother.

I’m glad to quote MLK. I think he’d be disgusted with the current Critical Theory/1619/BLM. I, like him, just want all men to be judged by the content of their character- the obvious implication… equal protection.

DAVID: Aaron, <<Me being jealous…does nothing to inspire me to continue pursuing excellence>>

I think this is mistaken. Your position relative to others matters for how likely you are to survive, what spouse you might end up with, what advantages your kids will get, etc. It would be evolutionary advantageous to have genes that made you care about how you compare with others. And, yes, our evolved feeling of jealousy serves exactly this purpose.

People get off on feeling ahead of others and have trouble with feeling behind others, and both of those motivate “keeping up with the Joneses” behavior. When people break down and just feel sorry for themselves is when they are so disadvantaged relative to others that they have no reasonable chance of not being behind.

I think it is good for people to understand how disadvantaged they are so they 1) won’t blame and feel bad about themselves for their outcomes in life 2) will be more focused on the real problem – the severe disadvantages that they and others face in our country.

I agree, incidentally, that the founding of our country was a HUGE step forward for humanity in terms of enhancing well-being. But there definitely was plenty more to be done then, and still plenty to be done today.

ROBERT: Chris, my insertion into the discussion was focused on the founders’ relation to their piece and how that is important. In that sense, my contribution was not related to the articles of focus, so it might be worth discussing the attachment of the founders in a different discussion.

Regardless, I think how the founders are viewed is less a historical question and more a philosophical one that has down stream impact upon the articles you and Aaron Bruce are discussing. I’ve been thinking about your comments a bit and here’s a not polished but structured response.

For one, Edmund Burke, the founder of modern conservatism had a tremendous emphasis on both the ideals and founders who made them. In his critique of the French Revolution in “Reflection of the Revolution in France”, he repeatedly admonishes the French for forgetting their founders’, and casting them away instead of venerating them and their principles. He then predicted the reign of terror a good few years before it happened. Conservatism as an ideology has placed importance on tradition and how that tradition was formed.

Secondly, attaching individuals to their action is a philosophical discussion in of itself. Why do we make monuments to some people, but for their actions? Stepping out of politics and into religion for a moment, to try to take Christ’s message but remove Christ is unacceptable in Christianity–granted unlike us, Christ did not sin and is the son of God. Moving back to government, politics, and philosophy, our founders spoke heavily about how we struggle with human nature, and Madison in his federalist papers acknowledge that government is the greatest reflection of human nature. From that basis, all fall short and if we were to have memorials made afterwards would have some reason for them to be removed. Either we choose to acknowledge the exceptional positive contributions of humanity or we should acknowledge no one.

Lincoln in his Gettysburg address honored the dead at Gettysburg not only because they sacrificed their lives, but because of their defense of the preservation and endurance of our founding principles.

“But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract.

The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

While dying on a battlefield is different from drafting the ideals those soldiers died for, is not crafting and dedicating a nation to those ideals not also worthy of those inspired by those ideals enough to defend them to their deaths? And is it not significant to recognize that the founders–particularly Jefferson–in writing those ideals considered their shortcomings as well? To have the humility to state a goal while saying you yourself fall short takes character.

Finally, yes the British did abolish slavery earlier because they had a more centralized system of government. An enlightened despot can end longstanding social ills through despotism. However, the people are then still not free. The founders as visionaries had a dilemma of a major social ill that was woven into the fabric of many states while also combating the despotism of Britain. If you read the Dred Scott speech I attached in my above comment, Lincoln accurately notes they did not have the power to solve both problems and get buy in from all the colonies. They sought to declare the right and as circumstances permitted the nation would shift in better alignment of those ideals. A change in character, particularly brought upon by oneself, takes tremendous time and effort. Declaring the rights to Life, Liberty, and Pursuit of Happiness while limiting government is the longer path to abolishing slavery. But it does prevent enduring despotism. In fact, it is the opposite model of Marxism. Karl Marx explained the Proletariat would seize the means of production, establish a strong socialist government to create equality, and then the state will wither away slowly into communism. The founders limited government and declared an ethos that the people attached themselves to and over time we have toiled hard to better align ourselves with that ethos while maintaining a limited government.

Russia, China, and other nations have taken Marx’s approach literally and they end up with neither a classless society nor freedom. Putin runs Russia and Xi Jinping runs China in defacto one party states that have a clear elites/commoners dichotomy. In contrast, while the US is still striving to uphold its ideals it has made substantial progress: abolishing slavery and removing oppressive Jim Crow era laws.

This whole 3rd point is yes, it is frustrating that America seems behind the times and slow to change. That is because we focus on finding the solution that results in growth of individual character, and not growth of government. That takes time. Much like how it took me two days to respond

AARON: thanks Robert, much better said than this ole construction guy could ever do. I appreciate your involvement in our group. Thanks for your encouragement to “be better’

CHARLES: Robert, awesome summary and, I believe, an accurate depiction of why it is so easy to be unfairly and often unjustly critical of good and great leaders and people for not being perfect enough. The fact is they did great things, the best they could, for future generations.

DAVID: Robert, I hope you don’t mind a little push-back, but I think it is mistaken of you to claim that the reason that positive changes aren’t made in the States is because “we focus on finding the solution that results in growth of individual character, and not growth of government”.

Who do you mean when you say “we”? Maybe some people look to create “growth in individual character” but other people definitely find public policy solutions (i.e. government) to be more effective. What do you even mean by “growth in individual character”? I think there would be growth in individual character if we could be more respectful of women’s decisions about carrying pregnancies to term, but I know some people would completely think the opposite of that. I think that phase ultimately doesn’t have much meaning.

Yes, your statement is a feel-good, yay-America sort of statement (which lots of people definitely like), but I don’t think there is really any data to support it. If you have good reason to think it, though, I would be interested to hear it.

ROBERT: David, by “we” at the end of my comment, I mean the US governing model’s emphasis on individual freedoms in contrast to the one party states of Russia and China. I am not talking about each and every individual.

After the Constitution was created by the Constitutional convention, Benjamin Franklin was asked what kind of government we have. His response was “a republic, if you can keep it.” The task of upholding our inalienable rights and preventing despotic government falls on the responsibility of the individual. Our Democratic Republic depends on individuals who respect the rights of all and act to preserve them. If the people do not, then government acts, risking despotism. Lincoln explains this issue in his Lyceum Address, that if people do not respect the law, if they fail to allow due process and instead act for themselves out of passion and violence, then despotism is inevitable.

So my statement is not data driven or empirical, it is qualitative–as most of my comments have been. It’s commentary and a reflection of the political theory our government was designed on. It’s really what our system of government expects us as individuals to do in order to function at its best. Unlike Russia and China’s governing models that demand obedience to the party or government through force, our model focuses on individual freedoms and utilizes federalism, separation of powers, and checks and balances. These tools allow the people to prevent government from becoming despotic, provided the people generally stick towards prioritizing our founding ideals.

DAVID: Robert, I appreciate the clarification. I think I better understand you now. So, I believe you are saying then that our governing model focuses on solutions that result in the growth of individual character (and that is why we are slow). I don’t know of anywhere in the Constitution that suggests that, and that doesn’t sound like something that would be in the Constitution, but can you direct me to any passages that do suggest that?

I don’t care about quotes from founders or former leaders because they made zillions of quotes (many that even contradict each other), and people from all sorts of different political perspectives find quotes to justify almost anything. Besides, such quotes aren’t the law of the land (that would make us slow or fast to change), only the Constitution is.

CHRIS: Aaron, Robert, and David, there’s so many important things to respond to, I doubt I can touch on them all. But first, let me start with what you said, Aaron.

Yes, of course vandalizing statues is wrong, and of course I recognize the symbolic significance. I’m certainly not calling for, or approving of, statues of any founders toppling.

Also, yes, my saying conservatives “deify” the founders is a distracting exaggeration.

But I think this is equally false: “a significant number of citizenry that have been falsely taught that the systems that [the founders] have created are inherently unjust.” That is NOT even close to the Hannah-Jones essay.

Could the fact that you hear “lip service to a halfhearted love of country” be due to your prejudice against the essay prior to reading it? You said at the start that you “fully reject the premise of their foundational argument that America’s ‘true’ founding was with the first trans Atlantic slave ship.”

But she actually writes: “the year 1619 is as important to the American story as 1776. That black Americans, as much as those men cast in alabaster in the nation’s capital, are this nation’s true ‘founding fathers.’”

And:

“Black Americans have also been, and continue to be, foundational to the idea of American freedom.”

The phrases “as much as,” “is as important,” and “have also been” are not about replacing the founders with an alternate single “true” narrative. They are about expanding our national narrative.

You also said she is “falsely pushing the idea that the system is rigged,” but her focus is entirely historical. She doesn’t say anything about today, let alone anything being rigged.

You even linked the essay to “the psychiatrist fanaticizing about killing all white people,” which would be guilt-by-association, except there is no link of association between Hannah-Jones and that psychiatrist in the news this week.

It seems this is the point that most disturbs you: “Our founding Fathers may not have actually believed in the ideals they espoused.”

But that seems self-evidently true to me. Yes, there is good evidence that, while practicing slavery, they ultimately foresaw and helped bring about the eventual end of slavery. But there’s also equally strong evidence that they believed black people to be innately inferior. Would the founders have been content with the Jim Crow America that replaced slavery? I don’t know. But abolition and equality are NOT even close to the same thing. Do you sincerely believe that they understood the phrases “all men are created equal” and “we the people” as we do today?

They were people of their time period. I’m not condemning them for that obvious fact. But I’m also not trying to erase what that fact actually means. Again, I think it’s NOT facing it that is divisive.

CHRIS: Robert, more briefly, yes, you’re right on multiple points, but some seem to move to other issues.

I trust your formidable knowledge that Burke foresaw the reign of terror, but your implied argument is that we therefore should revere our founders or face the same outcome. That is a two-hundred-year leap of logic based on a single data point. I don’t really see Burke providing much insight here.

We could also debate whether any memorials to individuals should be made, and perhaps none should—but memorials are a distant concern here, and not revering the founders (instead of the ideals expressed in the founding document) really has very little if anything to do with Lincoln honoring the war dead. Your implied argument is that not honoring the founders with memorials would be like opposing the Gettysburg Address.

Your third point is that the founders weighed difficult things and came up with the best possible balanced solution. Okay. But, again, that’s not really the question at hand. Let’s accept that’s true. They still personally profited from the grotesque despotism of slavery. They were still racists.

Why is that self-evident fact so difficult for folks to acknowledge?

ROBERT: David, as a historian contextualization is vitally important for understanding any historical document. The Constitution is itself a legal document, but it’s significance, purpose, and how it fits into the bigger picture of US history all depend on some form of context to give a greater understanding. To discount the commentary of the founders, I think, only serves to limit our understanding of the Declaration and Constitution, especially when considering how they relate to the concepts of inalienable, natural, and individual rights.

just like how in statistics, Data needs to be juxtaposed to see patterns, correlations, and in some rare cases causation. Historical documents only go so far when deprived of the context they were written in.

Case in point, the cooper union address linked in the initial post here, centers around the voting records of every signer of the constitution, concluding the vast majority believed it gave the Federal Government power to abolish slavery in the federal territories with only a small number of unknowns and 2 in opposition.

That being said, I will still respond to your question, not with quotes from the founders in their letters and speeches, but from the Federalist Papers, which were written to convince the different states, primarily the swing states of Pennsylvania and Virginia, of adopting the Constitution. Supreme Court justices across the ideological spectrum, from Ginsburg to Scalia, and from Rehnquist to Thurgood Marshall have relied on the Federalist Papers (and Anti-Federalist Papers) to better understanding the constitution as they gave the founders’ thought process in making the document. These papers will be the closest you can get to the founders explaining the constitution’s nuts and bolts and how they fit in the bigger picture.

Federalist 10 (written by James Madison) seeks to explain the structure of congress in how it addresses factions. Factions arise from every position under the sun. Our political parties are factions. The white working class would be considered a faction. Religious voters would be another faction. Any group that can have political objectives is a faction. Madison in Federalist 10 explains that in a governing system centered around freedom, factions are inevitable.

“Liberty is to faction, what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it could not be a less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.”

So the problem Madison is saying the Constitution needs to address is, since people will naturally politically group into factions and liberty encourages factions, how do we ensure factions do not infringe on the rights of others? We can’t do it by taking the rights away of particular factions that look like they have an advantage or seem undesirable, but rather by “mitigating the effects” and make it excruciatingly hard for a faction to have a lot of political power. That is the reason for the Bicameral congress. That is the reason for a Senate chosen by state legislatures an house chosen by population. That is the reason the court gets life terms by appointment and we keep that number small. That is why we have a whole separate and complicated electoral system that is the electoral college–which you, Chris, and I, I believe discussed before on how the founders had a very different view of the electoral college then how we do it today. Even if a passionate faction controls congress, it still has many layers to control before it outright dictates policy.

All of this to go back to Madison’s central message in Federalist 10. There are a lot of layers to prevent control of the government by a faction so that passion and mob rule does not hijack the system. Our governing system is not about making policies quickly. The roadblocks are actually a feature.

So how does this relate back to developing individual character? As a nation we are forced to stop, think, and deliberate on policies. National discussion takes time and helps people learn and grow when they get involved in civil discourse. Laws need the approval of a house, senate, president–unless VERY popular–and if challenged the courts, and even then if the people hated a particular law enough, they may elected a different body to congress.

In contrast, a governing system rooted in efficiently passing policy, such as the parliamentary system, or in extreme cases one party states, has less stakeholders at play in passing policy and is more likely to go with the mood of the prevailing faction of the day. Sure they may have a populist government that passes the policies that make people feel good, but there is less to prevent factions from using political power to stifle other factions.

Isn’t growing individual character an aspect of what this whole group is about? Engaging in civil discourse to understand others and help bring insight to understanding our inevitable factions so that we can be better informed participants in our system of government?

CHRIS: Aaron, Robert, and Charles, your concerns seem to focus on how Hannah-Jones and others criticize not the ideals contained in the founding documents, but the founders themselves, or, as Charles wrote, being “unfairly and often unjustly critical of good and great leaders and people for not being perfect enough.”

Instead of the founders of the US, let’s look at a very different founder of what is now considered a progressive institution that many conservatives routinely attack. Margaret Sanger founded Planned Parenthood. Sanger is feminist icon, but was also a racist and white supremacist. I’ve drawn attention to that fact multiple times myself, but it was only this April that PP did too.

Please read the attached letter by a current leader of the organization acknowledging for the first time just how “not perfect enough” Sanger was. I share this because I want to clarify that it’s not just our founders who need to look at through an unbiased lens. Perhaps seeing how a progressive organization assesses its own founder will give you a different understanding of how progressives feel the necessity of assessing all founders accurately. Just as today’s Planned Parenthood is not even remotely suggesting that its current mission is undermined by Sanger’s well-documented racism, progressives are not suggesting that America is undermined by its founders’ racism either. The undermining danger is instead NOT coming to terms with these pasts.

CHRIS: And if you won’t read the whole letter, please read these excerpts. I would very much like to hear your reactions and how this might relate to our discussion of the US founders:

“For the 11 years that I’ve been involved with Planned Parenthood, founded by Sanger, her legacy on race has been debated. Sanger, a nurse, opened the nation’s first birth control clinic in Brownsville, Brooklyn, in 1916, and dedicated her life to promoting birth control to improve women’s lives. But was she, or was she not, racist?

It’s a question that we’ve tried to avoid, but we no longer can. We must reckon with it.

Up until now, Planned Parenthood has failed to own the impact of our founder’s actions. We have defended Sanger as a protector of bodily autonomy and self-determination, while excusing her association with white supremacist groups and eugenics as an unfortunate “product of her time.” Until recently, we have hidden behind the assertion that her beliefs were the norm for people of her class and era, always being sure to name her work alongside that of W.E.B. Dubois and other Black freedom fighters. But the facts are complicated.

We don’t know what was in Sanger’s heart, and we don’t need to in order to condemn her harmful choices. What we have is a history of focusing on white womanhood relentlessly. Whether our founder was a racist is not a simple yes or no question. Our reckoning is understanding her full legacy, and its impact. Our reckoning is the work that comes next.

And the first step is making Margaret Sanger less prominent in our present and future. The Planned Parent Federation of America has already renamed awards previously given in her honor, and Planned Parenthood of Greater New York renamed its Manhattan health center in 2020. Other independently managed affiliates may choose to follow.

Sanger remains an influential part of our history and will not be erased, but as we tell the history of Planned Parenthood’s founding, we must fully take responsibility for the harm that Sanger caused to generations of people with disabilities and Black, Latino, Asian-American, and Indigenous people.

We will no longer make excuses or apologize for Margaret Sanger’s actions. But we can’t simply call her racist, scrub her from our history, and move on. We must examine how we have perpetuated her harms over the last century — as an organization, an institution, and as individuals.

We are committed to confronting any white supremacy in our own organization, and across the movement for reproductive freedom.”

AARON: The pendulum of society swings. I fear that when it swings back from the current “black only dorms”, “black only graduation ceremonies”, preference for admission based solely on the extra melanin in someone’s skin, you will have given your grandchildren ammunition that it is *acceptable* to use skin color to define who’s “more equal” and the minorities will be runnin for the hills.

I’m afraid that plenty of evidence points to the fact that essays like 1619 are being used to put a chink in the armor of the actual *ideals* of limited government, liberty, equal protection. To put in context, the Democratic party was a gnat’s hair from having an actual socialist as it’s presidential nominee (remember, his self-described defining distinguishment with Warren was, “she’s a capitalist”.) As you’ve mentioned yourself Chris, you struggled with the question on whether or not a college should be able to use skin color in their admission standards in order to artificially “help” or “hurt” people solely because of their race.

I stand by the assertion that the best path forward is a firm commitment to a completely blind Lady Justice with equal protection for everyone. We should be striving towards a color *blind* society. Instead, people like Hanna-Jones want us now, more than ever, to make sure everyone feels like the amount of melanin in their skin is the most defining attribute of their personhood. If Hanna-Jones believed in our founding ideals and was actually *promoting* them, she would have ended her essay by lambasting Harvard University for even *considering* a “black only” graduation…I have a feeling MLK would have.

In regards to Sanger and PP, I attack them because of their *ideals*. Sure, Sanger was a racist but the fundamental idea that one can kill life because it’s inconvenient is repugnant to me. I suppose someone could make a case that the reason *why* the life is inconvenient might make the act a little more or less repugnant but the fundamental ideal is primarily what I am attacking. I submit that’s exactly what Critical Theory/1619/BLM is doing with the founders and their ideals as well.

DAVID: Robert, I appreciate your thorough and detailed response. I’m going to disagree with you on how important historical contextualization is. I’m not saying that it is not important all at. It can perhaps provide some clarification when passages of the Constitution are especially vague. However, given the zillions of quotes founders made in their lives and given that each one was not of the same mind throughout their life, I think it is too easy for someone to manipulate the meaning of our founding documents by just finding some quote that goes along with what they already think, when that thought did not make it into the actual Constitution (so there has to be debate whether *one* founder’s thought at *one* point in time should tell us what our country is).

I do think, though, that it is very much of *historical interest* to understand who the founders were. But I think you are mistaken in suggesting that discounting their commentary only serves to limit understanding of our founding documents. It might do that, but it might serve to do several other things, and I would argue that it very importantly serves to prevent the meaning of those documents from being manipulated.

The Federalist Papers I do find to be more helpful, though. The quote you provided there from Madison essentially says that “liberty” is a necessary condition for factions and that we should have liberty. The quote does not make any statement about how much people will form into factions, nor whether they do so naturally (and there is actually good, modern social science on that topic). Moreover, it does not say anything suggesting how our houses of Congress are elected, life terms, electoral college, etc. (Perhaps it does somewhere else in the document?)

The quote also makes no mention of growth of character, which, again, is tricky because there definitely is not agreement about what character even is.

From my social science background (particularly public choice economics), here is a perspective on the efficiency of public decision-making within a democratic government (and I’m using the broad definition of democracy there, so that a republic would be a part of that definition):

You can’t have less than a 50% threshold for making a decision because no decision would ever be final (e.g. 48% could vote to switch us from policy A to policy B, then 52% would vote to switch us back to A, then 48% back to B, etc). So, 50% is the minimum (i.e. majority rule), and it is incredibly efficient. There’s no need for negotiations and the question just is, does the median voter like A better or B better?

The issue of course is that in majority rule, the majority can beat up on the minority. So, for the other extreme, why not a 100% threshold, i.e. unanimity? Then no one can be beat up on because everyone would have to agree on every decision. And, in principle, we could do unanimity — have the winners of the decision financially compensate the losers of the decision so that everyone is a winner in the end, and hence it is unanimous (this is effectively the key normative principle that underlies markets in economics; why we pay for things that people make for us).

The problem here, though, is that negotiations to get unanimity are exceptionally and prohibitively difficult. (Almost never can you get even a 100-member body to all agree, let alone everyone in a country.) So we have to settle on somewhere between 50% and 100%, and the public decision-making process from our Constitution does just that. And I would say that our Constitution does a pretty good job of finding a decent balance. We do make decisions, not as efficiently as majority rule, but definitely better than unanimity. We do have minorities (not necessarily racial) getting beat up on, but there are some good protections, too.

I definitely think the founders did a pretty good job, particularly for the late 18th century. But I think things could be better with what we have now (much better social science research for understanding human beings, better game-theoretic understanding of public decision-making, better technology for crunching numbers, etc).

For example, because of the dramatic disparities in the populations of states that we have now and also because of gerrymandering, it is something like 25% of voters can beat up on the remaining 75% (which is *worse* than the majority beating up on the minority). Again, our Constitution should be applauded for what it is, but for human well-being (what I care about ) I think improvements should be made.

(My apologies for my long tangent here, but maybe interesting nonetheless…)

CHRIS: Aaron, maybe I shouldn’t have brought up Planned Parenthood, since abortion is a massive and massively difficult topic to broach. My point was how an institution can deal with the racism of its founder, which you didn’t address or even acknowledge in your above comment. You also continue to make generalizations about “Critical Theory/1619/BLM” (saying they are “repugnant” because they “kill” the founders, which is not a metaphorical tangent worth addressing) even though you have now read exactly one 1619 essay and so you know first-hand that your claim is false. Your only shift is that you now say 1619 is “being used to” promote things you disagree with, tacitly acknowledging that those uses are missuses—though you still seem to think Hannah-Jones is to blame. You seem to judge things not by what they are, but what you think they could be used for. So instead of acknowledging the fact that the founders were white supremacists who personally profited as slave-owners and dealing with the ramifications of that fact, you want to place it out of sight because looking at it is “divisive.” If a political position requires suppressing facts because they are inconvenient, then I think that’s pretty good evidence that there’s something wrong with the political position. If you think reparations and so-called socialism are bad things, your current approach to fighting them is a strategy designed to backfire because resisting something that is true (the founders were white supremacists) will eventually and (I think) inevitably fail. So if your “firm commitment to a completely blind Lady Justice with equal protection for everyone” requires suppressing historical truths for fear that those truths could “put a chink in the armor of the actual *ideals* of limited government, liberty, equal protection,” then you are working against yourself. But if you instead stopped revering the “Founders” as secular saints and heroes and faced up to the depth of white supremacy at the time of the founding, then you would have a factually firm footing for your vision of moving forward.

AARON: I used poorly chosen words to finish my post….I didn’t mean that 1619 et al “kill” the founders…I meant that they attack the *ideals* of the founders. I specifically used the word “repugnant” when describing the murder of babies. What claim of mine is false? You have built a straw man if you think that I deny that racism has been in this world since Adam (and by obvious implication- our founders). You apologized once for saying that I deify the founders but you just said it again (secular saints). I know that they had warts. *nobody* denied that they had slaves. Just like nobody denies that it was warring African tribes that often “round them up” for the Muslims and Europeans to ship off. Just like no one denies that the first slave holder in America was a black man (if they read their history books). Just like no one denies that native Americans held other tribes captive. There’s a lot of sin to sift through in this topic.

DAVID: Aaron, I think what you should find more repugnant is making up supernatural baloney about when “life” begins so you can force women to carry unwanted pregnancies to term. I can’t believe that you think the tremendous responsibilities of parenthood are simply “inconvenient” (although I guess it depends on what type of parent you are).

AARON: David, this is the second time that you have tried to hijack Chris and I’s conversation. Start a new topic on “when does ‘science’ say life begins?”…personally, I’m currently not interested because I have my hands full with this topic. Maybe someone else would bite on it.

CHARLES: Chris, Aaron, David, great and thoughtful civil discourse, THANKS!!

I think my basic point, and it may have been supported by Chris and others, is that leaders are often mired in values and beliefs popular in their eras but they, in specific instances, rise above their documented bias or prejudice with the courage to do what is right. I think of Lincoln with the Emancipation Proclamation or Lee and Grant treating each other with respect and dignity calling for unity.

CHRIS: Aaron, I think we’ve hit a point where we’re going in circles. You continue to state that 1619 and others “attack the *ideals* of the founders” even though the one example we’ve looked at closely does no such thing. Yes, there’s certainly “a lot of sin” all around, but we are currently looking at the “sins” of the founders. Saying that others also committed terrible sins is unquestionably true, but none of those others jeopardize the ideals expressed in our founding documents if their sins aren’t reckoned with and separated from those documents.

Charles, I agree with you that Lee and Grant ended the war in a way that prevented years of protracted guerilla warfare and terrorism, and I sincerely commend them for that. I also commend our founders for the Declaration and the Constitution because they contain the core ideals of equality that our nation has continued to progress toward. I also find deep faults in many of their other behaviors which are certainly “mired in values and beliefs popular in their eras.”

So I think we are in agreement about the ideals, which is by far the most important thing. We disagree about how to preserve and further realize those ideals. It seems you (Charles, Aaron, Robert) think that revering the founders is the best way to do that. I (and many other progressives) think that that reverence is instead dangerous and divisive. So despite having a shared goal, we can’t seem to come together about strategy.

DAVID: Charles, definitely don’t forget Robert! Although we having a nice back and forth about the Constitution and the Founders, I definitely have to appreciate his deep historical knowledge and the detail he provides in his very thoughtful comments.

AARON: So, we’ve agreed that we probably shouldn’t teach our children that keeping slavery was the impetus for the revolution. Yes, we might be going in circles. You wanna tackle the next essay, “In order to understand the brutality of American Capitalism, you have to start with the plantation.” By Mathew Desmond?

DAVID: Aaron, this is at least the 50th time that you have been grossly mistaken in declaring someone else’s motives. You made a highly controversial comment, and I shared my perspective on your comment. There is no hijacking. If you didn’t want your comment to be discussed, my suggestion would be for you to not include it in the conversation.

CHRIS: Aaron, yes, I agree that keeping slavery was not the impetus for the revolution, and therefore we should not teach our children that. Do you agree that our founders were white supremacists, and therefore we should acknowledge that fact to our children?

CHRIS: Honestly, I wouldn’t mind a breather, but, yes, I’m happy to read another 1619 essay together if you would like to. But would you mind starting a new post and make an invitation to anyone on RCDS to read the essay and participate?

CHRIS: Also, would you all mind if I copy and pasted this thread into my person blog as a (significantly better than average) example of a RCDS conversation?

ROBERT: I don’t mind.

AARON: no problem

AARON: Yes, I agree that our founders were white supremacists. If we are going to assert that truth to our children, then the context *must* include all the other sins from other races that I’ve been bringing up that is part of this conversation. Part of the problem I see is that without this context, it gives the appearance that white males are *particularly* bad and America’s founding was *uniquely* sinful. Bottom line, in the 15th-18th century our world looked *very* different than it does today (even though there’s plenty of slavery in our world today).

If a child is going to hear that our Founders were white supremacists, then he needs to be told that different ethnic Africans “rounded up” the African Slaves, Asian Muslims participated, the first permanent slave *owner* in America was black, and the Native Americans also practiced slavery.

CHARLES: I do not mind as we always want to promote quality civil discourse!

CHARLES: David, thanks for reminding me of Robert as he contributed very well.

DAVID: Chris, I don’t mind at all.