Monthly Archives: October 2019

31/10/19 Apologizing for an Absurdly Absent God

Ben O’Neil is a devotee of surreal absurdism. His Apologetica—a collection of seven short comics, ranging from two to twenty pages, plus a three-page illustrated prose story—is difficult to describe. I mean that in a good way. Though the title references a defense of religious beliefs by Roman-era Christians, O’Neil’s focus is not Christianity or even religion generally, except in a reversed sense, the absence of a meaning-providing God in a world of mass-produced plastic crap literally held together by chewing gum.

Three of the comics feature “Mr. Martyr,” a self-flagellating cartoon that has more in common with SpongeBob Squarepants than the riff on the iconographic Christian martyr adorning O’Neil’s book cover. Though both figures sport paper-white skin, the torso-less Mr. Martyr’s hose-like limbs protrude from his circle of a head. If he had an actual body, the BDSM vibe would be even more extreme. Mr. Martyr loves abuse, and though he speaks through the fourth wall of his panels for readers to spit on him, no one does. His three-part adventure is a quest for meaningful torture, but how’s that possible when no one is paying attention, and you’re just one torture-seeking fanatic in a world of almost identically drawn fanatics?

O’Neil uses a 2×2 panel layout for his Mr. Martyr pages, a very traditional format (Jack Kirby had a thing for it too) that offsets the non-traditional subject matter. Though other chapters vary layout, they remain rigidly rectangular with unbroken frames that center their content with poster-like clarity and simplicity. O’Neil’s secular hell is not crosshatched with naturalistic details but stamped in place by a blunt instrument. His lines are consistently sharp-edged and colored in undifferentiated blocks of yellow, red, pink, blue, and black. The effect is intentionally garish and so well-suited to the consumer-culture critique.

The ten-page “Trash Culture” is the most defining. Global warning results in biblical-level flooding and the discovery of a continent of floating garbage. But instead of an ark, survivors board a cruise ship, and instead of a dove returning with a land-promising olive leaf, seagulls carry back used syringes. When a couple hundred years of asylum-seeking immigration and procreation renders the island too small, new factories produce new plastic crap, eventually expanding the landmass into an all-encompassing crust across the planet.

Though prophetic, the absurdist parable is less about the future and more about the U.S. right now. Interestingly, O’Neil draws his critique of consumer selfishness with very few consumers. Occasional individuals appear in panels (the murdered cruise ship captain, three warring soldiers), but most feature distant angles of inanimate objects. Rather than highlighting acts of gluttonous consumption, it’s as if the objects of consumption have consumed their consumers. We have literally replaced ourselves with human-shaped trash.

My favorite of O’Neil’s selections is “The Sentient Loin,” a demonically pro-vegetarian horror tale in reversed white and red art on black pages (a little reminiscent of horror artist Emily Carroll’s most recent comic, When I Arrived at the Castle). Although the events unfold in standard story fashion (the main character purchases a loin chop at the supermarket, eats it, and plunges into a monstrous dream state), O’Neil’s visual storytelling works more at a symbolic register. Instead of spatiotemporal snapshots following the logic of a movie storyboard, the images represent their content from a greater, iconic distance. The microbe of meat coursing through the narrator’s bloodstream is the smiling face of the supermarket’s mascot. The perfectly round hole that the narrator digs to bury the remaining loin descends into the page in red concentric strips like a target sign. Did the narrator somehow actually dig a hole like this? No. It’s an image once-removed from the visual content it visually represents. It’s an image of an image. Like the narrator who purchases her animal flesh prepackaged in containers that obscure the circumstances of the product’s creation, O’Neil’s readers are weirdly removed from the story too.

The visual distancing approach is most extreme with the inclusion of a prose story. While stand-alone words are an obvious norm of prose fiction, the inclusion of three double-columned pages of prose disrupts the visual norms of comics, while also revealing the weirdness of non-comics visualization. When we read words in prose, we picture things, but when we read words in comics, we see the pictures that surround and so define the words. But suddenly O’Neil gives us “Entire Tinyhouse,” a story about Hubert, a dissatisfied billionaire longing for a Thoreau-esque experience of nature. Does Hubert have the absurdist body of Mr. Martyr or the human proportions of O’Neil’s cover martyr? Is Hubert’s skin the same page-bright white as all of the other characters? The answer is all of the above. Or none of the above. Hubert doesn’t exist visually in the same way as the comics characters who surround him. He’s just words and whatever vague, pseudo-images a given reader experiences mentally.

Though Hubert’s nature trek comes to a tragic end in keeping with O’Neil’s overall apocalyptic tone, Apologetica is not all doom and destruction. There’s even an undercurrent of hope under all the surreal absurdism. Happy ending might be too strong a term, but when the last oil well runs dry in “Trash Culture,” humanity does take “its first collective breath.” And though still haunted by her meat-induced horrors, the narrator of “The Sentient Loin” does escape her immediate hellscape, now apparently a fully devoted vegan. Even Mr. Martyr reevaluates his life, realizing that suffering is not divine punishment and that the pleasure of friendship has more meaning: “If only I’d noticed sooner …”

O’Neil and his readers do notice sooner—though that hopeful undercurrent is mostly swamped by the massive tide of plastic crap washing ashore the shores it creates. If O’Neil is apologizing for any God, it’s the nihilistically indifferent one who maintains our self-inflicted, capitalistic marketplace.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Apologetica, Ben O’Neil, Popnoir Editions

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

28/10/19 Redoubtfully (or, “Why I Shouldn’t be Fired for Teaching Comics,” Part 3)

Last week I published a blog post titled “My Ongoing Attempts to Reason with the Generals Redoubt.” In retrospect, I should have called it “My Ongoing Attempts to Reason with Neely Young” because Neely Young was the only person from the alumni group that I interacted with. He is, however, one of its three founding members and leaders. He told me that he writes all of the essays distributed to their email list and posted on their website. He called himself their “idea man.” So while my impressions of Neely are specific to Neely, they apply to the Generals Redoubt to the degree that he shapes the organization. He said running it is like his full-time job. I believe no other member is fractionally as involved.

My impressions of Neely are based on his essays (starting with the one denigrating two of my courses), a lengthy email exchange (included almost verbatim in my post last week), and two separate in-person meetings totaling more than two hours (and four coffees). I think this is a fairly solid basis for drawing impressions about someone, though I don’t want to overgeneralize since I’m sure there are many positive aspects of his character that I haven’t had the chance to observe.

But in short, I will no longer be attempting to reason with Neely. I will try to explain why, but if you are not inclined to trust my assessment, I urge you instead to read the email exchange I posted last week and draw your own conclusions. The post includes no commentary from me about Neely, and roughly half of it is Neely’s own words. He paints his own portrait.

I offer my assessment of Neely here in order to support the following recommendation: if you are a member of the W&L community, whether faculty, student, administrator, or alumni, you should not expect to engage with Neely in meaningful conversation. I have repeatedly tried and failed.

This is disappointing to me because I especially value conversation between people from opposing perspectives. I co-founded the Rockbridge Civil Discourse Society in order to bring conservatives and liberals together in open-minded, stereotype-challenging dialogue where both sides learn and, ideally, find and expand common ground. I believe that compromise is not a necessary evil but a profound good that should be embraced by all members of a community like W&L’s. Neely does not agree.

Though Neely uses the words “conversation” and “communication” and “discussion,” he does not mean the same things by them as I do. He wishes to have his opinions stated to as large of an audience as possible, whether online or in the debates he’s trying to organize on campus. A debate is the opposite of a conversation. A debate is a polite fistfight. Each side listens to their opponents only to detect and exploit weaknesses while never exploring let alone acknowledging weaknesses of their own viewpoints. A debate reinforces divisions and undermines any hope for forging common ground.

Neely and I also appear to be using different definitions of the word “opinion.” When I say opinion, I mean an informed opinion as opposed to a gut reaction. We all have gut reactions. They are necessary and inevitable. But after experiencing gut reactions to something, I consider it our job to educate ourselves about the topic by gathering verifiable facts and using them to evaluate our initial response and develop an informed opinion. Sometimes my informed opinions match my gut reactions; sometimes they don’t. Regardless, a gut reaction is only a starting point, never an end point.

Neely seems to have experienced a gut reaction to the words “superheroes” and “comics” in my course titles. Based on that reaction, he called my courses inane, frivolous, trivial, dubious, and of questionable value. But to be able to state such opinions meaningfully, Neely would have to know at least a little about graphic narratives, the analysis of pop cultural icons, contemporary literature, studio arts, and writing pedagogy. I tried to help him develop an informed opinion by sending him two of my scholarly essays, which he said were “excellent,” though I have yet to see any evidence that he read either of them. Prior to our second coffee, I selected five graphic novels that I thought would expand his knowledge about comics, but he refused to hear a word on the topic. I was also going to give him examples of graphic narratives that won or were nominated for the most prestigious literary awards in the English language (Pulitzer, National Book, Booker, MacArthur), but he cut me off.

As I said repeatedly to Neely, comics are irrelevant to the larger issues facing W&L. I attempted to engage with him about comics so that he could demonstrate his ability to engage meaningfully on a topic of some kind, with comics providing an easy, low-stakes building block toward more difficult issues. He would not engage. He would not acknowledge that his opinion was uninformed, that he had made no attempt to learn anything about my courses before disseminating his opinion about them to 8,000 alums, and that he ignored my attempts to provide information afterwards. When I asked him to explain why he held his opinion, he refused. He would only repeat his claim, as though the fact of his stating it was evidence of its truth.

What if instead of comics we had tried to have a meaningful conversation about the legacy of Robert E. Lee at W&L or the continuing importance of the honor code? How do you talk to someone who forms strongly negative opinions based on gut reactions, does not educate himself about the topic, refuses others’ attempts to provide information, does not offer evidence for his opinions, and refers to those opinions as “the truth”?

I don’t care that Neely thinks comics are stupid. I do care that Neely has convinced a group of well-intentioned alums that his opinions about the state of W&L are accurate and that its traditions are under attack by liberal professors out to destroy their alma matter. If any reader thinks W&L is facing such an “existential threat” (Neely’s phrase), it will take more than a blog post to build trust between us. It will take a lot of conversation.

Neely did offer me a quid pro quo: if I would agree to help him organize public debates on campus, he would not post his “Dumbing Down the Curriculum at W&L” essay at his website. I declined.

Though Neely and I agreed to shake hands and amicably part ways, I remain open to the remaining 7,999 members of the Generals Redoubt’s email list. I believe in the importance and sincerity of your concerns, and I believe your commitment to W&L is one of the many many things that make our school so excellent. I also suspect you have some inaccurate impressions about the current faculty, the student body, and the direction the school is headed.

And I’m happy to talk about that.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

24/10/19 Amplify This

Amplify is not your typical textbook—and not just because 115 of its 166 pages are comics. Professor Norah Bowman selected seven feminists and feminist organizations, transformed their histories into stories with the aid of playwright Meg Braem, and then handed those scripted stories to comics artist Dominique Hui to transform into graphic narratives with the aim of motivating new acts of feminist resistance from inspired readers.

The focus is intersectional, so in addition to the white women of Pussy Riot and Rote Zora, the collection highlights mostly international women of color. Since the press is the University of Toronto’s, two of the seven narratives appropriately take place in Canada—with a Canadian cameo concluding a third. The U.S. appears only once, as do India, Russia, Liberia, and Germany. The inclusion of a South American narrative would have completed the range of continents, and the omission of a Muslim feminist (Malala Yousafzai perhaps?) is equally disappointing. But the project offers only a sampling, not a canonical list of feminist icons. The field is rich. Instead of seven narratives, future editions of Amplify could include 14 or 21 and still not be definitive.

Since the focus is primarily and usefully on the 21st century, the two 1970s narratives do seem oddly placed. They’re also atypically violent, featuring the only firearms and bombs employed by protestors. Most of the vignettes instead highlight the power of modern media: TV, online petitions, YouTube, Twitter. This matches the collection’s pedagogical focus, since readers are far more likely to reach for their cellphones than for Kathleen Cleaver’s rifle. And though Rote Zora’s 45 fire bombings have somehow resulted in no injuries, no textbook can or should provide the necessary basics of skill and luck that requires.

Bowman’s basics are more academic, including a 24-entry glossary of such terms as ‘lateral violence’ and ‘heteronormativity.’ She discusses the more centrally defining term intersectional feminism in her introduction, urging readers’ local communities and grassroots organizations to combat multiple kinds of oppressions. The goals are lofty, though also classroom-focused, with reading lists and discussion questions capping each chapter. As much as I appreciate a well formatted Works Cited, is an inspired community action group going to interlibrary-loan an essay from the Journal of the American Academy of Religion or spend time discussing questions better suited to reading quizzes (“For what crime were the women of Pussy Riot imprisoned, and how long was their sentence?”)?

I debated at times who Amplify is most addressing since the 11- to 22-page comics communicate their content with rudimentary directness. While the historical events might welcome critical engagement—when, for instance, is it okay to fire bomb a porn shop?—the graphic adaptations echo the narrative logic of children’s tales, condensing time into summarizing dialogue that replaces what it represents. When Kathleen Neal, for example, appears in the doorway of the Blank Panthers meeting room after the arrest of Huey Newtown, her speech balloons declare: “I’m Kathleen Neal, from Atlanta. I understand there’s a crisis in the organization.” A member shouts: “They arrested Huey!” A 100-word caption box spelled out the facts on the previous page, making the response redundant. Bowman’s afterword (she includes one for each chapter) is redundant too, repeating much of the same information covered by the comic.

The afterword also produces contradictions. Though the graphic narrative implies that Kathleen Neal traveled to California to join the Black Panthers in response to Newton’s arrest, Bowman later explains that Neal had already met her husband, Black Panther member Eldridge Cleaver, and took up Newton’s cause only after becoming a member herself. The difference is perhaps minor—and I appreciate the authors not portraying Neal as an appendage to her husband. Still, the contradiction is unnecessary and situates the comics as something other than exacting nonfiction.

The Leymah Gbowee comic treats time similarly, presenting a 2,000-woman protest on the outskirts of Monrovia, Liberia as Gbowee’s first organized event and combining it with a march outside the parliament building as if the two were consecutive actions by the same gathering of people. Bowman explains afterwards that Gbowee didn’t just send “out a message to the women of Liberia hoping they would come,” as her talk balloon states. She co-founded the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace, a religiously diverse organization that undertook multiple actions, culminating in the parliament march and peace talks that eventually resulted in the collapse of the Charles Taylor dictatorship.

Again, Bowman’s afterward expands on the comic, adding absent nuance. While this is helpful, the effect is odd since Bowman co-wrote the comics and so helped create the gaps she later fills. Why not just script the comics differently? According to the preface, playwright Meg Braem was “in charge of storytelling and drama,” and so the based-on-a-true-story condensing is presumably hers. The juxtaposition of the two narrative forms, the comics and their prose-only afterwards, are potentially intriguing, but the result here is neither a harmonizing whole nor a structured point-counterpoint but a surprising undercurrent of mistrust in comics to represent history independently of traditional scholarly apparatus. So I would augment Bowman’s reading lists with at least two more comics-specific texts: Joseph Witek’s Comic Books as History (University Press of Mississippi, 1989) and Hilary Chute’s Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics and Documentary Form (Harvard University Press, 2016).

The third author, freelance artist Dominique Hui, used Bowman’s photo archives to illustrate the scripts, giving her pleasantly loose ink style a different kind of authenticity. While her black and white rendering remains largely consistent, her layouts vary with each chapter and often each page, reflecting the ever-changing topics. She also displays the occasional visual flourish—the diagonal lines of lyrics emanating through the full-page Pussy Riot concert panel is my favorite. I also admire her careful vacillation in reproduction sizings. When Leymah Gbowee’s portrait narrates in present-tense, the lines of her head and clothing are granularly thin with meticulous detail, but her flashback images are enlarged to create thicker, bolder lines that further contrast the two time periods.

Though I’m not sure if these comics ultimately amplify their subject matters or merely alter them through a different medium and documentary ethos, Amplify’s goals are laudable and their results engaging.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Amplify: Graphic Narratives of Feminist Resistance, Domique Hui, Meg Braem, Norah Bowman

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

21/10/19 My Ongoing Attempts to Reason with the Generals Redoubt (Or, “Why I Shouldn’t Be Fired For Teaching Comics,” Part 2)

Last winter an alumni group distributed an essay titled “The ‘Dumbing Down’ of the Curriculum at W&L” to their mailing list. My courses Creating Comics and Superheroes were in the top two slots for courses that the unnamed author considered “of dubious academic value, dedicated to the espousal of a political agenda, trivial, inane, or some combination of the above.” The author suggested eliminating these and other courses and also “eliminating some of the professors who teach them.” I responded in my blog post “Why I Shouldn’t be Fired for Teaching Comics.”

The author of “Dumbing Down,” Neely Young, emailed me in September with multiple attachments including a “response to your post of May, 2019. As we say, we would have responded sooner but we were not aware of your post.” He added: ” I really think we all should realize that, at this point, any communication between us should be considered as in the public domain. That is, unless both sides agree to confidentiality in advance.”

I wrote back: “I would be happy to sit down and chat. Shall we get coffee some time?”

Neely: “I would be more comfortable meeting with you after you have had a chance to read over all of the material. I think it would make our conversation more productive. I’m not saying that you have to respond to anything which I have written prior to our meeting, although you are free to do so. I’m saying that some of my ideas about how we might move forward in increasing communication between the various parts of the W&L community are sort of embedded in my letter. We can talk further about this when we meet.”

Chris: “I had already read the newsletter and I read your letter to me and the short essay regarding Chavis and Robinson before responding. Since you said you didn’t want “to litigate past differences of opinion but to discuss ways to improve communication,” I didn’t respond to any of the content. I can of course respond to the content in person or by email, but my main interest is in finding common ground and that’s probably done best by sitting down together.”

Neely: “I couldn’t agree with you more. Just let me know when and where you would like to meet.”

We met at Lexington Coffee. Neely emailed afterwards thanking me, saying he “enjoyed our conversation,” and suggesting that we meet again with other members of his alumni group: “I am thinking the focus should be on possible public, on campus meetings to discuss recent developments at the university and its future direction. I am also thinking that it would be good if we could find some topics to discuss initially where compromise or agreement could be reached among the various university constituencies. I welcome your thoughts on this. As I said previously, if you would like to ask another faculty member to accompany you to our next meeting, that would be fine.”

Chris: “I’m glad we met for coffee, and I hope to continue to expand our better understanding of each other. With that goal in mind, will you do me the honor of reading some of my research? I’ve attached two articles that I think might provide some sense of the work I’m doing in relation to your “Dumbing Down the Curriculum” paper.”

Neely: “I will certainly read it, but I am not sure I am qualified to comment on it. I am sure there is something to be learned from any area of study.”

Chris: “As a published historian with UVa Press, you should be more than qualified.”

The essays I gave him were “The Well-born Superhero,” published in the Journal of American Culture, and “The Ku Klux Klan and the birth of the superhero,” published in the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. Both trace the development of the superhero character type through the eugenics movement in early the 20th-century U.S.

Neely contacted me again in October. After describing the Generals Redoubt’s new website, he wrote:

I have now read both of the essays which you sent me, and I am afraid that I am in pretty much the same position that I was before you sent them to me. That is, I have almost no familiarity with the subject/s upon which you are opining and do not feel qualified to comment. I will say that I think your research and writing are excellent and that you are certainly qualified from a scholarly perspective.

This is not the same thing as saying what or what should not be included in the curriculum. But that is a subject for another day. Indeed, I would like to meet with you again at your convenience and would like to bring a friend with me. Barry Brown lives in Lexington and is a former parent. Her family has been involved with Washington and Lee almost since its inception, and she is a member of the Executive Committee of The Generals Redoubt. The main thing I would like to discuss is how we might move forward in setting up some on campus forums, panel discussions, etc. involving various elements of the W&L community. However, I am open to discussing any other issues which you like. I am also open to your bringing someone else with you if you like.

I would also like to say that I have revised my essay on “Dumbing Down the Curriculum” to delete any mention of eliminating faculty positions. This is not my place or concern. Otherwise, the essay is pretty much the same. I will be publishing the revised edition in upcoming material on our website.

Chris:

Good to hear from you. Congratulations on launching the website—I know personally the challenges involved—and I look forward to reading your new essay “Ideological Diversity.” I’m also pleased to hear that you have decided to drop the part about eliminating faculty positions from your “Dumbing Down” essay.

May I ask if my courses will still be featured at the top of the “Dumbing Down” list? While I acknowledge there are some differences between scholarship and teaching, W&L as you know encourages a teacher-scholar model, and my work especially reflects that. The idea for “Superheroes” came from a group of honors students who sought out a professor willing to develop and teach a syllabus on their behalf. When they found me, I had done no research into superheroes or comics, but I said yes, and that has since led to four books, two from the University of Iowa Press and two from Bloomsbury. I also have a contract under way from Routledge for a fifth.

If you consider my research and writing to be excellent, it would seem odd if you maintained that courses based on that research could be “of dubious academic value,” “trivial,” and “inane” as you previously stated. At that time your opinion was based only on the names of the courses—which is why I accurately accused you of conducting “shallow research” last spring on my blog. Having read the two essays I forwarded, you now know at least some elements of actual content covered in the courses. When we met for coffee last month, you seemed like a reasonable person, and so I find it difficult to believe that you could still characterize my teaching as “dumbing down” W&L’s curriculum. Am I mistaken?

Neely:

Thanks for your prompt reply. It is my opinion that the courses which should or should not be offered at W&L is a discussion we can save for another time. I am thinking that this can be a part of the public forums which could take place on campus. When I say a part, I mean that there could be a broad conversation about what constitutes a quality liberal arts education. As I said, what I would like to do is set up another meeting with you and my colleague, Barry Brown, to talk about the possibility of setting up these public forums and discussing what topics might be discussed at these forums.

Chris:

I agree course offerings is a general topic that can be discussed in a public forum, but my concern is more specific and immediate. Honestly, I’m startled that you want to include “Dumbing Down” on the website. I thought you’d let that one quietly go. It is not very good. I don’t mean that I disagree with its opinions (which, as you know, I do); I mean its opinions are poorly presented. I disagree with opinions in your other essays, but they don’t suffer from the same weaknesses. Your writing in your summer newsletter, for example, might earn a B in my Writing 100, but “Dumbing Down” wouldn’t receive a passing grade. This is because, as I explained in my blog post, it shows “bias, shallow research, inadequate argumentation, and hypocritical rhetoric.”

You objected to that assessment when you wrote me last month, implying it was based on my disagreeing with your opinions. I disagree with many of your opinions, but the assessment applies only to “Dumbing Down” for the reasons I carefully detailed. You also wrote: “I have read your arguments for maintaining courses in Comic Books and Superheroes, and, although I appreciate your perspective, I am not convinced by your arguments.” But I explicitly stated: “I do not feel the need to present counter arguments.” Since I didn’t make any arguments for maintaining my courses, it is not possible for you to have been convinced or not convinced by them.

That you could imagine that you read such arguments does not reflect well on your reading skills, but I have a much larger concern. You have now read two of my “excellent” essays that emerged from my superhero and comics courses, but you still intend to keep those courses on your “Dumbing Down” list, continuing to call them inane, trivial, frivolous, and of dubious academic value.

You also expect me to help you organize campus forums and panel discussions with faculty. To do that, I would have to assure my colleagues that you are a reasonable person who is sincerely open to meaningful conversation. But a reasonable person would not draw conclusions about courses based only on their titles. A reasonable person would also not continue to malign a professor after acknowledging the excellence of his research and writing.

You said in your letter that “we will have to agree to disagree.” I had hoped that we could instead develop common ground and bring opposing sides of the W&L community into better understanding and compromise. But if you can’t change your stance about the comparatively inconsequential issue of my courses, then continuing our conversations seems pointless.

Neely:

I do not intend to argue with you about all of these points. It seems to me you are getting into a lot of semantics here. For example, when I said that I was not convinced by your argument, perhaps I should just have said that I am not convinced at this point that such courses should be taught. What difference does it make how it is stated? At this point, I am still not convinced that such course should be taught. But I would rather focus on some things about which we might be able to find agreement rather than on things about which we disagree. For example, I can see a series of public forums taking place on a series of topics such as ideological diversity, curricular matters, the legacy of Lee, freedom of speech and expression, etc. You use a lot of strong language like saying that I lack “reading skills” and am attempting to “malign” you, that I am not a reasonable person, etc. It is almost as if you are seeking excuses for not having another meeting. If you would like to meet with me again to discuss how we might move forward in creating a dialogue between faculty, students, alums, and other members of the W&L community, I am glad to do so. If you do not, then I suppose that is the end of our conversation. However, I will note that you are the one ending this conversation, not me. We will continue to work with others to create dialogue among the various elements of the university.

Chris:

You said you “would rather focus on some things about which we might be able to find agreement rather than on things about which we disagree.” I shared my articles with you in the hope that we would come to that sort of agreement. I thought that because your initial claim was made in ignorance (I mean that literally not pejoratively), once you learned something about my actual course content, your opinions would evolve. You said you’re “still not convinced that such course should be taught,” but there’s quite a distance between that position and your continuing claim that my courses are inane, trivial, frivolous, and of dubious academic value. In what sense are you not disparaging me? Why do you object to my “strong language” but not your own?

You said you want my help organizing “public forums” on topics including “curricular matters.” Why do you want to discuss these matters publicly but not privately with me? My goal is to bridge differences between opposing viewpoints in our community. If the forums would help achieve that, then I would support them. But your emails suggest that you are not interested in bridging differences but only in maintaining and more widely espousing intractable opinions.

Looking over your previous email, I hear the unpleasant echo of a reading quiz where a student creates the impression of having done the homework but on rereading I see there is not a single reference to content of any kind. I selected those two articles because their arguments are historical, and you are a historian and so should “feel qualified to comment.” How is it possible to feel unqualified to comment on my essays to me privately and yet continue to feel qualified to comment to your 8,000-member mailing list on my courses (about which you know only their titles)?

Instead of taking insult at your “Dumbing Down” essay, I have been trying to engage with you personally. The so-called inanity of my courses seemed like an ideal side topic because it has nothing to do with the main focus of the Generals Redoubt and so I thought with a little mutual effort and openness we would arrive at a better understanding, one that could be a stepping stone to wider growth. You said to me over our first coffee that your essay “wasn’t personal,” meaning you had no idea who taught my courses when you wrote it. You no longer have that luxury. We know each other. We sat and talked for 90 minutes. That should have been the first step toward something better.

And perhaps it still will be. I am happy to meet with you again, and with Barry Brown (I hope she has made a full recovery from her surgery). But please understand that my goal is actual conversation. I have no interest in helping you build a soap box to espouse opinions that you maintain in the face of greater counter evidence. That is my working definition of “unreasonable.”

Neely:

Here is what I am willing to do; I hope you are willing to do the same. If not, I will understand. I am certainly willing to meet with you again. I am willing to discuss further with you the topics which you raise in the email you sent to me, but I am not willing to do so ad nauseum. It is possible that at the end of the day, we will still disagree on some of these issues. Even if we do, I don’t see why we can’t move forward in setting up some public forums to discuss these issues on campus and involve people with different points of view. You may see it as a “soapbox”, but I see it as an opportunity for all sides to discuss issues which I feel were not adequately discussed before the issuance of the History Commission report and the directive of the Board in fall, 2018.

I will say that my language was not directed at you personally, but at the course which you are teaching as well as some other courses. I do not see this as disparaging you. I am interested in a broader discussion of what a quality liberal arts education should look like. The question of which courses should be taught is a part of that discussion but not the only part. I am willing to change my language from “trivial and frivolous” to something like of “questionable academic value” I say this because this is how I feel at this time. You say that my emails indicate that I may not be interested in bridging differences. I am interested in bridging differences where I can, but, frankly, I am more interested in the truth and in helping to make Washington and Lee the best place it can be. It may be that in this process, some people’s feelings may be hurt. That is not my intention nor the intention of the Generals Redoubt; neither is it our primary concern.

I suggest than we meet we have a discussion on how we can do more to bridge differences while still maintaining our particular points of view. I suggest we spend as much time as possible focusing on how we can set up public forums where all of these issues can be discussed among the various elements of the W&L community.

Chris:

As I said, I’m happy to meet. Feel free to suggest a time.

I’m glad you’re removing “trivial and frivolous,“ but you continue to miss the key question: on what basis are you making any judgement? If you instead wrote that my courses were excellent (as you said of my research and writing), that statement would be equally uninformed. You only know the course titles. You wrote in “Dumbing Down”: “Do we really need classes in comic books with so much great literature to study?” Creating Comics is not focused on the study of literature because Creating Comics is not a literature course. You would know that if you had done even the very most basic step of research and read the course description. It is a joint creative writing and studio arts course co-taught with a drawing and printmaking professor. Do you know literally anything about drawing and printmaking? Are you also unaware that Superheroes is a section of Writing 100 and so also not a literature course? Writing instruction is an enormous, decades-old field of study. Have you read literally anything in the field? You said you don’t want to discuss these issues ad nauseam, but you have yet to take even a first, rudimentary step.

My hope was that you would demonstrate intellectual curiosity about things that you know nothing about and yet feel qualified to judge publicly and loudly. In doing so you would demonstrate your ability to learn. Obviously, my courses have nothing to do with the History Commission report and the Board’s directives. If you are incapable of engaging meaningfully with the content of my work, how can I hope that you will do any better on issues of actual significance to our shared community? Your “truth” regarding my courses is based in willful ignorance. You said, “I don’t see why we can’t move forward in setting up some public forums to discuss these issues on campus.” This is why.

Please demonstrate that you are an individual capable of open-minded conversation who cares more about learning and bridging differences than creating a platform for espousing uninformed opinions.

Neely:

Thanks for your response. I have spoken to Barry Brown, and we can meet with you any time on Thursday or on Friday morning. Why don’t you pick the place and time? We can meet with you anywhere that you feel comfortable. Perhaps Barry can help us bridge our differences. I think we can discuss all of the things which you mention at our meeting.

We have our second coffee scheduled for later this week.

Wish me luck.

[The saga continues here.]

Tags: Generals Redoubt, Neely Young, Washington and Lee University

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

17/10/19 Was Walt Whitman Gay?

Depends on your definition of “gay.” The word didn’t have anything to do with sexuality during Whitman’s lifetime. It’s meaning may be anachronistic too. Not that 19th-century men weren’t having sex with each other, but they likely weren’t categorizing themselves along a gay-straight dichotomy. “Bi” would have been alien for the same reason.

But whatever your preferred word and definition, the most famous American male poet appears to have had some highly non-platonic feelings for other men, as expressed in his twelve-section long poem “Live Oak, with Moss.” Whitman writes in the opening section:

“the flames of me, consuming, burning for his love whom I love … my life-long lover.”

If you think “love” and “lover” might have non-sexual meanings, the third poem is clarifying:

“my heart beat happier … for he I love was returned and sleeping by my side.”

If “sleeping” still isn’t overt enough, consider how he describes two men departing on a pier:

“The one to remain hung on the other’s neck and passionately kissed him—while the one to depart tightly prest the one to remain in his arms.”

So, yeah, Walt was totally gay.

This should matter to poetry fans for a range reasons—not least the new edition of Live Oak, With Moss published by Abrams this spring. This should matter to comics fans for the same reason, since artist Brian Selznick receives equal billing as Whitman’s co-author. Their same-sex collaboration should delight both fanbases.

Whitman started “Live Oak, with Moss” in 1856, not long after self-publishing the first edition of Leaves of Grass. He finished it in 1859 by handwriting the twelve sections into a handmade notebook—which is included in the Abrams edition in the form of eighteen, meticulously reassembled color photographs. It’s clear from a glance at Whitman’s ragged script and penciled cross-outs that the notebook was still a work-in-progress. When the individual poems appeared in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass, they were revised, divided, and redistributed into a larger sequence.

Live Oak, with Moss not only restores the original poem “cluster” (Whitman’s preferred term) but significantly adds to it. Selznick’s art consists of fifty-six two-page spreads. Forty-eight precede the poem (which fill only fourteen pages), with a coda of eight. In terms of page count, Selznick is by far the primary author. While fans of Selznick’s children’s book collaborations The Invention of Hugo Caret and Wonderstruck should recognize his style, the images may surprise. Eight of them are intensely intimate, colored-pencil close-ups of ambiguously cropped nude bodies in sexual contact. They are not pornographic. Selznick draws no genitalia. He draws no faces either. The most distinguishable features are fingers and brightly red nipples. The dark folds and sloping expanses of meticulously cross-hatched skin are landscape-like, bordering on abstraction.

If you worry that the great American bard is being resurrected in an anachronistically sexualized context, look at the first edition of his Leaves of Grass. I mean literally look at it: Whitman’s unattributed portrait appears as the frontispiece. It’s not just that his pose is cocksure (fist on hip, hat at a jaunty angle), but his actual cock is prominent. Whitman had the artist add more detail to the crotch.

According to Karen Karbiener, whose thirty-page afterword provides much appreciated biographical context, Whitman modeled “Live Oak, With Moss” after Shakespeare, who he considered a “handsome and well-shaped man.” He was especially taken by the sonnets and their subject matter of a “beautiful young man so passionately treated” and “ancient Greek friendship.” He was sure Shakespeare had been in love with the Earl of Southampton. Karbiener is sure Whitman was a patron of New York’s Pfaff’s beer cellar, “what may have been America’s first gay bar.”

Selznick’s art includes six adapted photographs of mid-century New York streets and buildings, with black and white male nudes collaged in their windows. Whitman’s flame-filled silhouette stands apart in page corners, until the urban background transforms to black and then a star-speckled sky. Whitman and a period nude move from their opposite corners, enlarging into sprinting poses before meeting at the page fold and erupting nova-like.

But is Live Oak, With Moss a comic?

Depends on your definition of “comic.” Whitman died in 1892, roughly the year the word began to refer to cartoon images in new newspaper sections and humor magazines. By the end of that decade, comics included panels, gutters, talk balloons, and other conventions associated with the form, but entirely missing from Selznick’s art. So if you’re expecting a caricatural version of Whitman declaiming his poetry in expressive fonts and word containers divided into a sequence of panels that illustrate their content like movie storyboards—this is not that. Selznick isn’t adapting Whitman into a visual narrative. He doesn’t even incorporate Whitman’s words into is art. The two modes, language and image, never combine, never even appear on facing pages. They are distant lovers, as divided as Whitman and Selznick are as collaborators.

Still, there’s a reason Abrams named its imprint “ComicArts.” Selznick responds to Whitman’s numbered but non-narratively ordered cluster by developing its verbal imagery into tightly sequenced and linked visual progressions. It opens with an incremental movement toward and then into an oak, revealing a world of dueling flame and water beneath and beyond its bark. Other images, such as the concluding pages of pure red and white configurations that resolve into impossibly red branches on an impossibly white background, would be at home in the anthology Abstract Comics. Another sequence uses its white space to depict snow mounting page-by-page inside a rustic cabin, until the snow banks become the absolute whiteness of the page itself, and so the backdrop for the black ink of Whitman’s words. The entire sequence ends with the same black and white rendering of an oak in full foliage that opens the book. All these wordless images meditate on Whitman’s poetry, suggesting the internal explorations and struggles layered in the poet’s expansive language.

So, yeah, Live Oak, With Moss is totally a comic. One of my favorites I’ve read this year.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Brian Selznick, Karen Karbiener, Live Oak, Walt Whitman, With Moss

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

14/10/19 The Lost Comic Book of Adam Nemett

That thirteen-page sequence is from Adam Nemett‘s novel We Can Save Us All. Except that it’s not. All though We Can Save Us All is a superhero novel, it’s not a graphic novel. There are no pictures. I had the pleasure of inviting Adam for a campus visit last year, and the students in my advanced creative writing class quizzed him about the writing process, publishing, and his novel–which is about a superhero cosplay club of college super-geniuses who save the world for their senior project (drugs are involved). I’d like to continue that conversation, but specifically about these graphic pages of his non-graphic novel.

Chris: How did these pages come about, and how do they relate to the novel?

Adam: These pages were created way back in 2009-10, when I was first developing the idea that the self-made superheroes in the book help create their own legend by distributing comic books depicting idealized versions of their exploits. These pages were created by an illustrator named Orpheus Collar (yes, his given name; when he was about 13 years old he realized he had one of those names that meant he couldn’t just be an insurance salesman or something. With a name like Orpheus, he had to be really really good at something. So he became an incredibly talented artist and exactly the kind of mortal superhero I was writing about: http://www.orpheusartist.com).

I met Orpheus when he was an undergrad at Maryland Institute College of Art, where my father has taught painting for about 50 years. Orpheus and I first collaborated on a pitch packet for a separate graphic novel idea called SHADES, and it looked pretty awesome but we ultimately got shot down by some pretty impressive folks at places like Vertigo, Dark Horse, etc., but hey, we went down swinging.

Around the same time I’d finished a rough first draft of the novel that became WE CAN SAVE US ALL. In this iteration, the novel shifted style/formats intermittently–some chapters were written as campus newspaper articles, as police reports, as epic poems, etc. (I’d been reading too much Watchmen at the time) and I thought a comic script would make obvious sense. But ultimately, the script was just a blueprint for sequential artwork, and I thought it could be interesting and innovative to actually see the script illustrated and include a sketched-out version of it in the manuscript.

It stuck around for a while, but ultimately when the book was about to go out on submission, my agent felt that it broke the flow of the narrative and had the potential to confuse or turn off publishers/readers who are suddenly being asked to shift to this unfamiliar format. The content of this scene also needed to change, and rather than trying to produce a new batch of illustrations, the decision was made to render the scene in prose and just keep things moving. But I still like the comic and how it mixes form and content.

Side note: I remember reading Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven and wishing that I could actually see the comic that her characters keep describing. Maybe publishers just don’t have much of a stomach for hybrid novels that mix genres/forms like this. Not yet, anyway.

Chris: When Mandel visited W&L, I asked her if she ever considered making a separate graphic novel. She said it almost happened, and that Craig Thompson (of Blankets fame) was interested. But then she got too focused on other projects to write the script. And maybe that’s for the best? Things can dramatically transform when they change mediums. When I read the above section of your novel, and the novel in general, it was ambiguous to me whether or to what extent these characters were heroic. Here the visual version is much less ambiguous: these are the bad guys. Did it trouble you to lose the effect of the faulty narration?

Adam: That’s a great question, and yes, absolutely, I think that was a key reason why my agent recommended cutting this visual section. My goal was to pace the book in such a way that readers are essentially wooed and inspired by Mathias (“here’s a guy who might have the answers!”) and, like David, ultimately have a hard time resisting the urge to follow him. I still read the book and feel, especially in the early stages, that the USV and its young leaders ARE good guys doing what they feel is right, responding in a compelling, theatrical and valid way to the global and local challenges they face. I don’t think I ever advised Orpheus, the illustrator, to render these characters as either good or bad guys, but the vibe is undoubtedly sinister and I think that essentially tipped my hand way before I wanted readers to definitively feel one way or another.

In general, I think that’s why you don’t see many instances in literary fiction of visually representing fictional characters. A good written description of a character should form a soft-edged image in the reader’s mind. When you watch a film, especially, but even in a graphic novel, the casting and visual rendering of a character can’t help but influence the reader/viewer, a subtle narrative version of “leading the witness.” When we see Brad Pitt playing a certain character, we bring the baggage of who he played in other movies, who he is in real life, how much money he was probably paid for this movie, the notion that he’s probably going to be a good guy, that he’s not going to die in the middle of the movie, etc. When we read characters in literary fiction, we shouldn’t have any of that baggage. Characters should be strangers until we get to know them and see how they think and act, which allows readers to form completely fresh opinions of the character at the outset and in every scene that follows.

Chris: Do you think writing graphic novels could be in your future?

Adam: Despite everything I just said about not wanting artwork to sway the opinions of fiction readers, I get really excited about the potential of the graphic novel–as its own medium and as a kind of precursor to film/tv–and I’d love to try my hand at it someday. I’d be open to writing completely new stories or relaunching classic superhero characters with new storyarcs, and I still harbor thoughts of working on an adaptation of We Can Save Us All into a full-length graphic novel. As with other adaptations of literary fiction, classic and contemporary, it’s an interesting way of broadening the audience–maybe bringing more literary fiction fans to the graphic format and vice versa–and given all the superhero themes in my book it’s probably an easier leap to make than The Handmaid’s Tale or Kindred or Jane Eyre (all have been adapted into comic form).

I really like the process of writing comic scripts, where you’re essentially speaking to a one-person audience (the illustrator) so you have free reign to describe each page and panel in a way that’s very customized to that reader (“in this panel we’ve got a low-angle shot of something like that skyscraper pic I emailed you, but more purple”) and where you can provide more or less detail depending on how the illustrator likes to work (give me more direction vs. don’t micromanage me). If I’m honest, the endgame sometimes feels like film/TV–that’s how so many of us receive our stories and probably the way to reach the most individual people these days–and the graphic format is obviously a great stand-in or interim step, basically storyboards for a screen adaptation. There’s so much that can be done in the graphic novel, but I’ve watched We Can Save Us All play out in my head so many times, with music and choreography and the kinds of elements that are difficult to place on the page, and it would be a thrill to see someone adapt it into a series and take it in compelling new directions that I never considered.

Tags: Adam Nemett, We Can Save Us All

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

09/10/19 Picasso Comics?

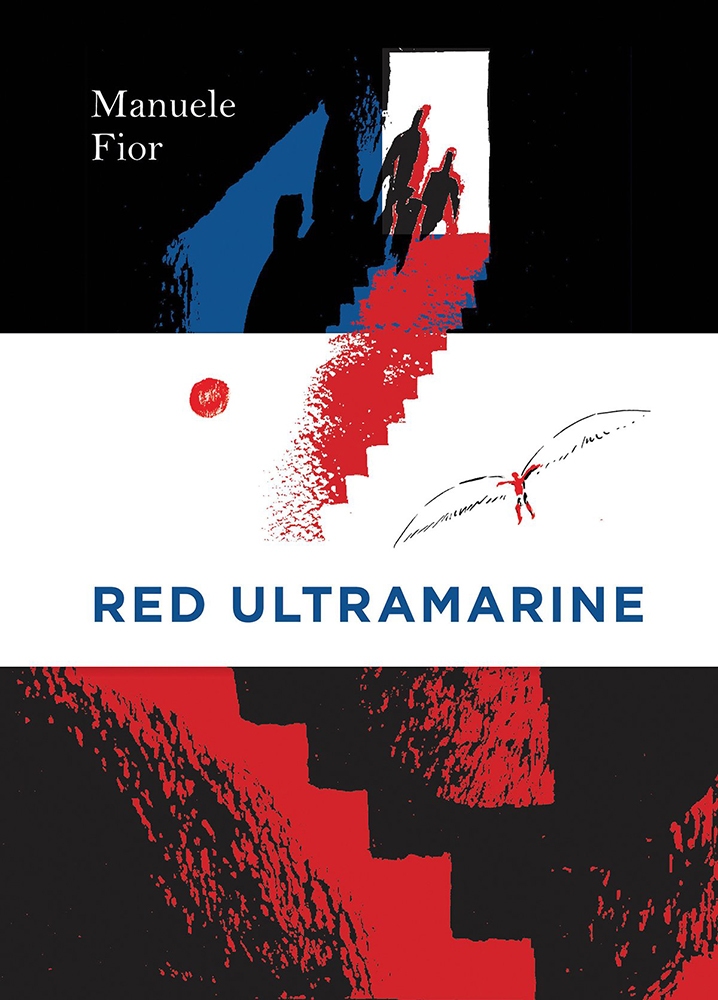

If Picasso had drawn comics, they might look like Manuele Fior’s Red Ultramarine. If that sounds like ridiculously high praise, it is. But some caveats: I mean “drawn” not “painted.” Late in his career, Picasso changed to minimalistic line drawings that no art critic has ever, to my knowledge, called “cartoons.” And yet they meet the definition: simplified (no depth-producing cross-hatched shadows, just the fewest pen strokes) and exaggerated (expressively stylized and so distorted contour lines instead of reality-reproducing ones). Look for yourself here:

Second caveat: Picasso was a sexual harasser, sexual assaulter, and statutory rapist, but, thankfully, Fior’s art is not infused with that same misogynist energy. I say that despite the two female nudes featured in the first five pages. Though Fior’s artistic eye never lingers so adoringly on any of the male figures in his novel, none of which are ever nude, the opening images take a complex meaning within the surprisingly sprawling (only 150 pages yet such interlocking time periods and plots) scope of the novel.

It’s rare to find a comics creator, or even a pair of writer and artist collaborators, who produce a work that is as equally impressive visually as it is narratively. Fior originally published the novel in 2006 as Rosso Oltremare, which Jamie Richards translated from Italian for the Fantagraphics Books edition released last spring. The publisher also brought Fior’s 5,000 Km Per Second to English readers in 2016. There Fior works in watercolors, an evolution of style that the English publication order reverses, since Fior drew the more minimalistic Red Ultramarine first.

The novel epitomizes artful restraint by using only two colors: black and red. I’m not certain of Fior’s medium (the intentional patchiness of the reds suggest print-making to me, but the blacks tend more toward opaqueness), but it results in thick, expressive lines and shapes that push well beyond mere information-communicating illustration. Much of the novel’s power, and so meaning, is at the level of the brushstroke and the energy it conveys about the story world.

The two-tone approach and lack of depth-clarifying crosshatching sometimes turn panels into visual puzzles that must be paused over to decode, especially when motion lines and emanata are rendered in the same gestural style as physical objects. Fior is wise to draw consistent black frames in predictable layouts of two and three rows, each row a page-length panel or divided in half (except for the full-page panels opening half of the eight chapters). The orderly structure offsets the more anarchic panel interiors. Once in a great while I still found an image that I could only partially decode, an indication that its abstract qualities (the directions of the strokes and the complexities of their overlaps) are more important to meaning than what they represent at a literal level. The style slows “reading” by encouraging and rewarding careful attention. While Red Ultramarine is far from abstract expressionism, it is a pleasure to find an artist-writer who regards the art of his images to be equal to the narrative they convey.

And those images do tell a hell of a narrative, or two interlocking ones that, like the artwork, are pleasantly difficult to summarize. The back cover would have us believe that this is the tale of a mad architect (inspired, I assume, by Fior’s own degree in architecture) and his girlfriend Silvia’s attempt to save him. And it is that—and yet the first eighteen-page chapter takes place in mythic Greece and features a very different architect, the labyrinth-building Daedalus, and his son Icarus catching fish on the shores of Crete. Fior does not insult his reader’s intelligence with setting-defining captions, but instead lets the father-son dialogue slowly reveal all we need to know. The second chapter then leaps without explanation to a contemporary European city (Paris, Rome, I’m not sure, but Fior includes enough architecturally specific buildings that I suspect a more cosmopolitan reader would identify), and then, because of the vacillating chapter structure, we don’t even meet Silvia’ boyfriend until chapter four—which is also the only chapter he appears in.

The story centers on what Silvia comes to call a “strange correspondence,” in which characters and time itself are doubled. While Silvia’s boyfriend has an uncanny resemblance to Icarus, the doctor she begs for help in the contemporary setting is identical to King Minos, the villain who throws his imprisoned architect into his own labyrinth in revenge for the death of his son, the monstrous Minotaur. (Most of that action occurs off-page, so readers might want to do a quick brush-up on the original myths.)

The correspondence also extends beyond Greece to the relatively recent folktale of Faust as interpreted by the German poet Goethe, who is quoted twice in the text. Not only is the Doctor/Minos a variation on Mephistopheles, Silvia’s boyfriend is named Fausto. Given the inevitable fate of his twin-self Icarus, not to mention the damned Faust’s, you might assume a bad ending awaits the young architect. But Fior’s blueprints are more complex, preferring suggestive ambiguity over definitive closure.

There’s plenty more to pour over—a cryptic birthmark, magic time-travel ointment, an age-changing assistant, even a metaphoric justification for Fior’s artistic style when Deadalus reflects on how he designed the labyrinth, “making any point of reference uncertain, tricking the eye with winding passages.” The art and the story are similarly uncertain, with the reader-viewer’s eye and mind repeatedly tricked as we wander Fior’s own passages. But I’ll end on the cryptic title, since it references not red and black, the novel’s color motif, but red and blue—and so a color that only appears on the novel’s cover.

“Ultramarine” means “beyond the sea,” a reference to Afghanistan where the gemstone lapis lazuli was mined and then imported to Europe to be ground into the blue pigment first used by Renaissance painters. While Fior’s gesture toward a color his visual storytelling does not include could suggest a great many things, I experienced a metaphorical going-beyond of the surface world or worlds of the novel, as its story wandered into ambiguous territory, the undefined spaces beyond Fior’s gutters. It’s a disorienting mental and visual space, more difficult to map than most comics labyrinths, but also more rewarding.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Manuele Fior, Red Ultramarine

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

07/10/19 Impeachment Comic

This began as a photograph of Trump taken the day that the transcript of his phone conversation with Ukraine’s president was released. The transcript is five pages long, so I incrementally distorted the photo with gaps and overlays and new gaps, and then superimposed each version over one page of the transcript. I’ve been drafting a book on comics theory during my sabbatical, so I’m inclined now to bore you some terminological analysis.

There are at least four competing definitions of the term “comic,” and this hits three of them. It’s a comic in the formal sense of a sequence of juxtaposed images. It’s a comic in the publishing sense since I’m posting it at a comics-focused blog and calling it a comic. It’s even a comic in the cartoon sense because it distorts its subject into a caricature. It also hits the original cartoon genre of political satire. It is not, however, a comic in the conventions sense. I suspect some viewers might look at it and not mentally register “comic.” That’s because it avoids many conventions: it’s photo-based instead of drawn; there are no talk or thought bubbles; no moment-by-moment action happens; the column arrangement doesn’t evoke the layout of a comics page; and the gaps between the images don’t look like the traditional gutters of most comics.

Here it is combined into a traditional 4×3 grid layout, complete with discrete panels and consistent gutters:

I’m guessing it still doesn’t say “comic” to some viewers because there’s not a clear reading path, a convention present in most comics. While you can “read” it starting in the top left corner and following the rows down to the bottom left, I suspect many viewers will let their eyes wander freely.

I do think it tells a story, one of the most common comics conventions. It’s the story of Donald Trump’s incremental destruction.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

01/10/19 Does Science Fiction Make You Stupid?

The short answer: No.

Obviously no.

For the start of the long answer, look at the study I published two years ago with my colleague Dan Johnson in Scientific Study of Literature:

Or the write-up about the study featured in The Guardian:

Or at the two blog posts I published here with the unfortunately playful titles “Science Fiction Makes You Stupid” and “Science Fiction Makes You Stupid, Part 2.”

But to really get the answer, you need to read our new study due out in the next issue of SSL. Or the new write-up in The Guardian:

Looking back at the first study, “The Genre Effect,” we can now say that it wasn’t simply science fiction that triggered bad reading. It was non-literary science fiction. The new study, “The Literary Genre Effect,” instead shows that literary science fiction and literary realism trigger the same high-level responses from readers.

In other words, genre doesn’t matter. It’s the quality, stupid.

We also provide scientific evidence for something genre readers have known for decades: literary fiction and genre fiction are overlapping categories. Proving that required writing two short stories, one SF, the other narrative realism, that are also somehow identical so that their levels of literary merit are identical too.

So I wrote “ADA,” two 1,730-word stories that differ by exactly one word. The SF version has “robot” in the first sentence. The narrative realism version has “daughter.” Though the two groups of readers should imagine very different storyworlds as they continue, the texts and so the literary quality of the texts, will be the same.

I’m not claiming the story is great, just good, or at least good enough to be better than the stories we used for the first study. But judge for yourself. Though, unlike any of the readers in our study groups, you’ll likely experience the two storyworlds simultaneously. (I’ll also add that I don’t like the narrator at all. He somehow manages to be a total creep in both universes.)

Here’s “ADA”:

My _____________ (daughter/robot) is standing behind the bar, polishing a wine glass against a white cloth. She raises her chin and blinks at me as I slide onto the furthest stool. My throat feels raw, and I have to swallow once before forcing a smile and meeting her black eyes. They remind me of my ex-partner’s.

“What would you like?” Her voice is stiff, like an instrument plucking notes from a page of sheet music, the last one dutifully rising. It’s not like I had expected her to recognize me. She blinks again. “Do you want something, sir?”

I mumble, “White Russian.”

She slots the wine glass into the row of polished ones above her head and turns to mix the drink. Her movement is slow, precise.

“Light on the Kahlua,” I add, too loudly, as if delivering the punchline to a hilarious joke. She exhales what could be mistaken for a laugh, but keeps her back turned. I can’t help but study the way her neck moves, her shoulders, the joints of her arms, the whole slender skeleton. I helped make all that. Not that I deserve credit. If my legal assistant hadn’t traced a paper trail to her last month, I still wouldn’t know she exists.

Her hip leans in sync with the tilt of the bottle she’s pouring. They put her in one of those ridiculous little bartender outfits, white shirt, black tie, black vest, black slacks—except leggings really, every inch pinching a curve into place. The shirt is tight too. My partner and I parted ways before our creation entered the world, still sexless, a blank slate awaiting programming. Now she looks like a twenty-year-old woman of ambiguous nationality, Middle Eastern maybe. Turkish. She turns with my drink and centers it soundlessly on a napkin square.

“Light on the Kahlua,” she says.

“Thank you.” I’m mumbling again, but she must detect the tone, can’t help smiling. Her teeth are an impossible white against her brown lips. Her fingers retract before I can reach the glass. They’re brown too, but not as brown as my ex-partner’s. She laces them in front of her, poised for the next instruction. Manual labor. That must be all they think she’s good for here. She can’t know she is capable of anything more, either.

The nametag on her front pocket reads “ADA.” I lean forward as if I can’t quite make out the letters. I could be staring at her breast for all she cares. The shirt is so tight dark flesh presses through the gaps between buttons. She doesn’t flinch, unaffected by the gawking squint of a gray-haired white man. I’m even pointing now, at her right breast, playing up the fake squint. “Ada?”

The nametag on her front pocket reads “ADA.” I lean forward as if I can’t quite make out the letters. I’m even pointing now, playing up the fake squint. “Ada?”

She nods, repeats the syllables as if scanning them phonetically from a screen. I doubt that’s her name. My eyes have drifted back up to her face and so she has to speak. “How is your drink?”

I forgot it was in my hand, both of my hands. I’m strangling it. The ice cubes clack my teeth as I slurp the top. “Perfect,” I say.

She flashes the same meaningless smile she flashed when she slid me the glass. Exactly the same. She hasn’t budged from her stance either, not so far from the bar edge as to suggest aloofness, not so close to imply intimacy. The drink recipes she must have memorized too, thousands probably—though she really did go light on the Kahlua. By which I meant heavy on the vodka, but maybe that is too subtle an inference. We didn’t set out to make the world’s greatest bartender.

At least it’s a decent enough place, plenty of marble downstairs in the lobby, dizzying view up here. I think my room might be ocean-facing too. I haven’t checked in yet. I almost didn’t get out of the cab. If there had been a night flight back out, I might never have left the airport. The pub inside the terminal glowed with neon logos as the bartender tilted foam from a pair of frosted mugs. I kept walking.

Ada’s bar is more upscale but, at the moment, barren. It makes no difference to her. Her arms are draped in front of her, wrist resting in her other hand. She could hold the pose forever, a fixture as permanent as the row of stools bolted to the floor.

“So,” I say. Her eyebrows rise as if she thinks I’m gearing up to something. I’m not. My fingers keep rotating the glass on the fake wood. What is there to say that she could understand? I suck another sip and ask, “You been working here long?”

“As long as I can remember.”

No smile that time, so the line must not be designed to be funny. I chuckle anyway. And so now she is flashing her white teeth again, the crinkles around her eyes deepening with my volume. It’s just stimulus response. Except her pupils aren’t centered on mine. They’re a few inches off, focused somewhere beyond my shoulder. They have been this whole time.

I twist to look at the wall-length window behind me. The black of the sky and the black of ocean must meet somewhere out there, but it’s all the same from here, and the swirl of stars puncturing it. I wonder whether she is looking at one in particular, whether she can imagine a world almost like this one orbiting it out there, whether it’s even a star to her—or just a needle prick of light. Each is probably no different to her than the flicker of candle light centering each table. I’m not sure if the candles are even real. It doesn’t matter, but I’m sliding from my seat to lean over the closest and see the tiny electric filament blinking randomly inside its wax shell. No, the wax isn’t real either, just translucent plastic molded in a drizzle pattern, the same one table top after table top, a constellation of them. They’re pretty though. Everything in the bar is perfectly pretty. I shouldn’t have come.

“One hundred and forty-one,” Ada’s voice declares.

I turn back round. “Sorry?”

She has moved forward, her stomach pressing the bar edge. But she’s still not looking at me. “One hundred and forty-one,” she repeats. She’s looking at my drink, which is in her hand now. She’s swirling it. “The stars,” she says,

When she looks up, I nod, reflexively. “The stars.”

My voice is an echo of hers, so no question mark, nothing to suggest confusion, but she must detect it anyway. “That’s how many you can see right now,” she explains. The finger of her other hand is pointing at the window behind me.

I’m nodding again, sincerely now. The stars. She must count them. Some hard-wired impulse, I guess, but still. I begin to rotate back to the window, as if to check her math, make sure she didn’t miss one along the curtain edges, but stop when she lifts my glass to her face. She squints at the milky gray murk, as if searching for something, a specific ice cube or a thread of undissolved color. I want to believe that the swirl is no swirl to her, but precise points of black and white, stars so tiny only she could ever see them.

“You don’t like it.”

“No, no,” I say, “it’s, it’s—” But I don’t know if she means the drink or the view. “It’s fine.”

The lip of the glass is only inches from her own lips, but I’m still startled when she tilts a sip and weighs it in her mouth for a long, unblinking moment. The ball of her throat bobs as she swallows and frowns. “Why did you make me change it?”

My mouth opens, but I don’t speak. She must mean the mix, the proportions, Kahlua, vodka, cream. The glass is still hovering next to her cheek.

“I prefer it that way,” I say.

“No, you don’t.”

Without turning her body, even her neck, she extends her arm and dumps the drink into the tiny sink at her side. The ice cubes crackle and skid against the wet metal. She gives the glass one, precise shake and lowers it soundlessly to rest upside. I hadn’t noticed the sink was there.

I slide back onto my bar stool, expecting her to mix another Russian, but she reaches for one of the glasses above her head instead. It’s true. I should have ordered wine before, and I wonder if she can compute my exact preference too, a dry red, one older than her. But then I notice the white cloth is in her other hand again. She settles the dome of the glass into her palm and begins rotating it again. I watch. It’s all I can do.

“What do you want?” she asks. I start to quiz her about the vintage years of her cabernets, but she is speaking over me. “The way you paused when you entered, how you kept me in your periphery as you pretended to look around, even the stool you picked, no one sits that far away. You didn’t come for a drink.”

I feel my face warming, my smile widening as I stammer an apology. I’m shrugging too, blurting the next inanity that flashes to mind: “I guess I just like the view.” Then I don’t say anything. She is still working the glass around and around. It’s pristine.

“One hundred and forty-two,” she says.

I feel my eyebrows rise high into my forehead, but she doesn’t look up, doesn’t explain.

Then I spin my stool and blink at the swath of stars outside. They look identical to me, but of course they are changing, increment by increment, all night. Her window, the building, this pointless resort, it’s all moving, the whole planet, everything is. She must know every shifting constellation, the machinery of their endlessly possible worlds.

I stare, blinking, waiting for the next pinprick to vanish or burst over the window edge. I can’t see Ada slot the wine glass back into its row behind me. I just hear the click, like a delicate gear.

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized