Monthly Archives: June 2020

29/06/20 To Zoom or Not to Zoom

My university, like most universities across the country and globe, is struggling with a range of questions about how to operate during the pandemic this coming fall. I’d like to address two of those questions:

1) Is a zoom classroom inferior to a traditional classroom?

2) Should professors decide whether to conduct their classes traditionally or by zoom?

The short answers are: no and yes.

First an admission: I was on sabbatical this year and so avoided the staggering task of pivoting mid-semester and turning traditional courses into remote courses. I did observe many of my colleagues (including my spouse) and a few students (including my son who finished the last quarter of his first year at Haverford at our dining room table) make the transition, and the census seems to be: online classes kinda suck.

But of course that was the census. How could a course shoehorned mid-stride into a format unfamiliar to both the teacher and the students work as well as the intended format? Taking that very specific context of suckiness as evidence that online courses therefore are necessarily sucky would be like listening to a novice during a first piano lesson and concluding that pianos are godawful noise-machines.

If you want to know what a non-sucky zoom class looks like, start by looking at zoom. If you instead start with your traditional classroom lessons and try to adapt them to zoom, suckiness will ensue. Find out what is uniquely effective about zoom and then build your lesson around those features.

Here’s an example. I recently learned that the whiteboard allows everyone to access it simultaneously. I can’t stress enough how unbelievably cool that is. The first time I made a tiny little check mark during a zoom meeting was the first time I felt like a fully present participant and not just a multi-tasker giving the person talking a fraction of my attention as I’m hidden by the looked-at-but-not-seen weirdness of the videocam.

The pedagogical implications are even cooler. Here are two:

First day of zoom class, students enter to see each of their names typed on the whiteboard in a different color/style with the instruction to “check in” by selecting the same color/style and drawing a check next to their name. That’s now their identifying color/style for the rest of the semester. Whenever I start a new whiteboard for a discussion segment, we’ll begin with an instant “check in” along the margin. Then whatever they place on the whiteboard (a passage from the reading that supports their interpretation, a circle or underline to isolate a phrase from a longer passage that I placed there) everyone recognizes it as belonging to the specific student. And these visual interactions are happening in conjunction with the regular verbal discussion, making the zoom discussion not a second-rate imitation but its own unique animal.

Here’s a goofier micro-lesson for getting everyone’s attention synced. Each student is assigned one facial feature (left ear, mouth, right eyebrow, etc.) and when I say “now,” they draw simultaneously to create a one-second class portrait. I’ll save one portrait from each day (did I mention you can save your whiteboards?) and create a slideshow for the last day of class. This is my own doodle, not a class portrait, but it gives you a tiny hint of the possibilities:

There are so many more ways to capitalize on features:

polling (pre-plan a sequence to weave through discussion, starting with a fully anonymous reading quiz)

backgrounds (for homework students select passages—or images if it’s one of my comics classes—from the reading and have the screenshots ready to display behind their heads)

screen sharing (yes, everyone can finally all be one the same page at the same time),

break-out rooms (AKA, “small group work,” a core to my teaching since the early 90s),

I could go on, but you get the point: Build from the tech up.

Which brings me to the second question: should professors decide whether to zoom or not?

My school has created a doctor-signed HR form for professors at high-risk for CV-19 to receive permission to not meet with classes in-person. That’s great, but zoom isn’t primarily an emergency teaching tool. It’s just a teaching tool. Plus CV-19 doesn’t apply only to zoom teaching. Traditional teaching won’t be traditional either.

A CV-19 classroom will require teachers and students to wear masks and to stay six feet apart. How do you get students into small groups while circulating between them to monitor and answer questions? You don’t. Zoom break-out rooms are pedagogically better. If you think running a discussion on zoom is clumsy, how will it go when everyone has to shout from behind masks? I like to pull my classes into tight circles, but the minimum circumference for a fifteen-person CV-19 seminar is 120 feet. Does anyone seriously think that’s better than a grid of unmasked close-ups on a zoom screen?

Happily my school included this statement in our “Returning to the Workplace” guidelines:

“The university recognizes that a hallmark of a W&L education is the personal relationships between faculty to students. These relationships are typically fostered through the in-person classroom experience, and to the extent that students are able to return to campus, in-person instruction is the preferred method of delivery. However, as has always been the case, all faculty may alter their pedagogical methods to include a range of strategies that ensure an interactive and high-quality offering. This flexibility is not altered by these guidelines. If uncertain, faculty should continue to consult with their department head and dean on such approaches.”

Since I’m now vice-head (or what I’ve been calling “helper chair”) of my English department, I invite my colleagues to consult with me if they’re uncertain whether zoom approaches can achieve interactive and high-quality pedagogy better than traditional approaches used in the non-typical and non-preferred constraints of in-person CV-19 classrooms.

But whatever they decide, the decision to zoom or not to zoom is theirs to make.

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

22/06/20 The Horrors of Pre-pandemic Dating

I keep seeing articles about being single during the pandemic, which makes this review from March improbably outdated. How could so much have changed almost literally overnight?

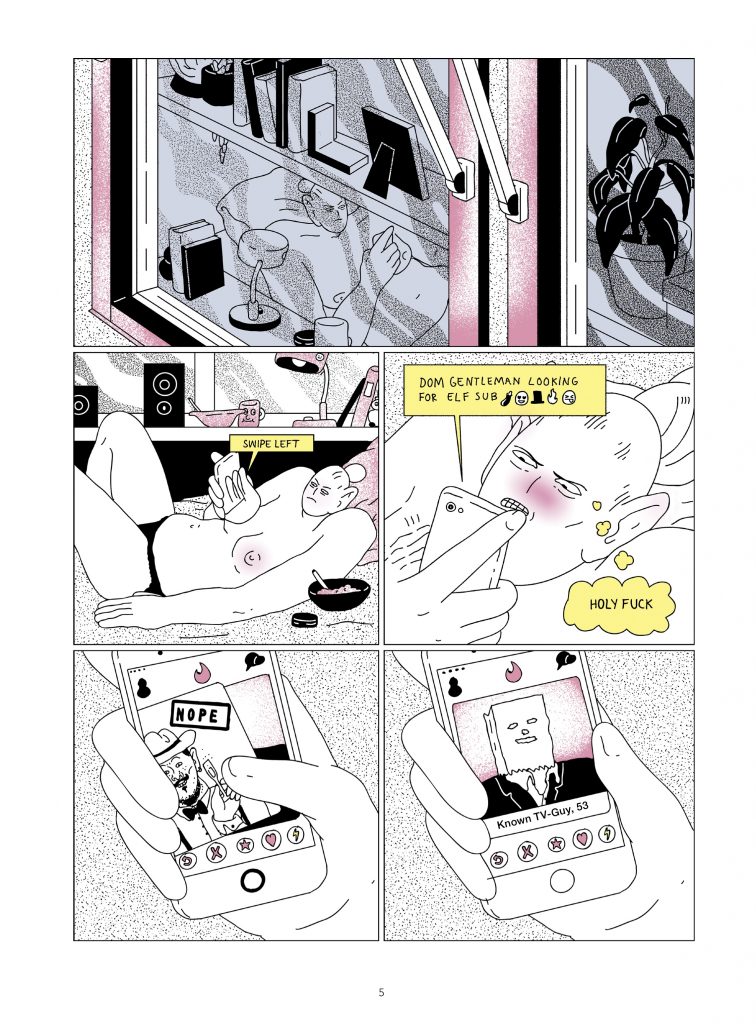

Goblin Girl opens with a partial nude. Moa is swiping through a dating app in bed. Her facial features are cartoonishly flat: single curved lines for mouth and nose, straight lines for eyebrows, ovals for eyes. Her body is simplistic too, mostly outline with an occasional squiggle to suggest naval or elbow dent, but those contours are distorted in a mostly proportional sense, leaving her tiny head and impossibly massive ears marooned atop almost realistically curving shoulders. She is an amalgam of slightly contradictory styles.

Romanova is from Stockholm, so it’s hard to trace the direction of influences, but her body is a pleasantly improbable combination of Canadian artst Michael DeForge’s hyper-cartoonish faces and U.S. artist Eleanor Davis’ not-so-feminine female forms. There’s something paradoxically attractive about a female artist drawing herself unattractively. Though attractive/unattractive is the wrong dichotomy. The image is neither erotic nor non-erotic. Her bare breast is brightened with the same pink as her annoyed cheeks and the scattered objects accenting the otherwise black and white art. Moa’s body simply is.

But that’s not quite true either. “Moa” isn’t necessarily even Moa. The publisher identifies Goblin Girl as “semi-auto-bio,” making “Moa” another kind of stylistic amalgam, a character marooned between the fiction/nonfiction dichotomy. Like the details within the images, her story events vacillate between the mostly realistic and the cartoonishly absurd. And what better place could Romanova explore the realistically absurd world of contemporary dating?

Moa’s older and inappropriately intense love interest is “Known-TV-Guy, 53,” who may or may not be a reference to The Unknown Comic from the 1970s Gong Show who also wore a paper bag over his head. Romanova kindly skips all but a verbal recap of the post-meet-for-drinks hotel bedroom scene, providing instead the one-page wandering of a street rat followed by other apparent digressions: Moa’s landlord has turned off the hot water in the showers because the tenants are slobs; Moa’s therapist thinks depression and anxiety attacks are best solved by deep breathing, pithy platitudes, and $120 bills. But soon Known-TV-Guy is texting again and explaining that, no, he didn’t actually mean he loved her when he said he loved her, he just feels a personal connection and wants to support her artistic work. So Moa figures: Why not? What could go wrong? (Plenty.)

Goblin Girl was translated from Swedish by Melissa Bowers, making English the graphic memoir/novel’s seventh language. That fact is intriguing since Romanova’s approach to words is as quietly contradictory as her artwork. The “SCRATCH” sound effect above Moa’s massive fingers is highlighted in the same yellow as the round-cornered speech rectangle containing Moa’s “HA HA HA HA” and, more oddly, the sharp-cornered rectangle containing the narration “SWIPE RIGHT” as Moa studies her phone. A page later Moa’s friend is apparently speaking Egyptian hieroglyphics to her, and sometimes Moa’s yellow thought balloons include graffiti-like block lettering and crude doodles. Other speech containers contain only unspeakable punctuation marks: double exclamation marks, double question marks, an ellipse. When the characters quote phone texts to each other, their spoken fonts shift from hand-written (or what looks hand-written) to a mechanical Helvetica. Though why does Moa pronounce “dot dot dot” and say “blushing emoji” in the same font? When Moa later opens the book “SHIT POETRY” by “ShitKid,” the words are in Helvetica too, but with a slight curve imitating the curve of the held pages. Even more oddly: it’s not a bad poem.

These subtle typographic details, like the details of the artwork, accumulate to produce a linguistic world as nuanced as its shifting visual world. Goblin Girl earns its seven languages. It includes probably the best description of depression I’ve ever read: “It’s like someone wakes you up in the middle of the night and is like, “Hey, I’m going out in the sub-freezing weather to dig an unnecessary hole. Want to come help? No coats allowed.” Moa’s Google searches are their own layer too: “John Hamm penis,” “Countries where lobotomy is legal,” “Finding Bigfoot streaming,” “Average lifespan Sweden,” “Sense of detachm.”

Romanova’s visuals of course require no translations, though viewers will be rewarded with a slow pace and a questioning eye. Why, for instance, is the panel of a dead cat in a bloodied box the most realistic image in the book? Her mother’s pet peacocks are weirdly intense too. The brief dream sequence bursts into garish color, but the subtle shifts to blue and green accents are even more intriguing. And why exactly does Moa suddenly transform into a Manga-style cartoon for a seven-page daydream? Oh, and is Moa’s mother actually a cartoon Moomim by Finnish illustrator Tove Jansson?

Though Known-TV-Guy resurfaces more than once, I’ll give one anti-spoiler alert: despite the backcover plot tease, Moa’s relationship with him is nowhere particularly near the novel/memoir’s core. It’s just a good hook to describe a depressed character-author’s wandering aesthetic that’s otherwise impossible to condense to an elevator pitch. Somehow lots happens and nothing much at all. Somehow her life is both chaotic (underground clubs, peeing in alleys, masturbating to porn) and humdrum (showering at a friend’s apartment, applying to art school, masturbating to porn). Moa is trapped between yet another unbridgeable dichotomy.

Ultimately though the only bridge she needs is between herself and herself. And building that is always an artwork-in-progress.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Books section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Goblin Girl, Moa Romanova

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

15/06/20 Washington and Lee and Floyd

From my Washington and Lee English Department:

Dear Members of our Community,

In September of 2017, the English Department published a statement to our students in which we condemned the neo-Nazi rhetoric and violence on display in Charlottesville earlier that summer. We still denounce white supremacy and the overt and insidious ways it operates, on our own campus and throughout the United States. This includes state-sanctioned white supremacist police violence, the deadly consequences of which resulted in the recent killings of Breonna Taylor, Manuel Ellis, Tony McDade, and George Floyd. The alarming frequency of these murders—to say nothing of the gross lack of accountability—must end. The clear inequities experienced by members of underrepresented and vulnerable groups, which are deliberate in a world organized by white supremacy, must end. The stakes are too dear to wait any longer. The current protests around the US and the globe show that we are not alone in this call for a more just world.

As educators, we are responsible for curating and protecting spaces of learning. As such, we have a responsibility to eradicate racism and prejudice from such spaces. We encourage our students to understand the world as a consequence of violent histories of race and racism, of slavery, of settler colonialism, and of prejudice on the basis of color, nation, custom, religion, gender, sexuality, and ability. In short, we challenge them to consider the many forms that policing can take. As literary critics and creative writers, we know that language holds the potential for disrupting racist ideologies, but we should not ignore the threat that language and hateful rhetoric pose in perpetuating racist systems and beliefs. We teach our students to be careful readers, to be thoughtful in their critiques, and to recognize the impact that they can have on their world.

We affirm the moral bare minimum: Black lives matter. But such an affirmation must only be the beginning of a more thorough process of dismantling the systems of oppression. We recognize and support those who take stands against racial injustice and demand another world. This includes protesters, of course, but also those who engage in the quotidian, unglamorous work of organizing, of providing care for the marginalized, of holding things together while so many go on about their lives. Indeed, care-work holds great potential to imagine a way forward. All of us will need to play roles in bringing forth a new world, but we honor those who have risked everything to show the way.

When we teach writing, we often tell our students that a conclusion is an excellent place to imagine what comes next. And in crafting this statement, we aim for it to be backed by action and for it to outline our next steps. Because lasting change arises only from group efforts, we wish to recognize and to support the work being done by members of our Lexington community, the greater Rockbridge area, and the state of Virginia.

To that end, we have collected more than $1000 for the Rockbridge County NAACP and their recently launched Irma Thompson Educators of Color Initiative. This decision is motivated by our wish to aid people who are already engaged in our community, have assessed a need, and have facilitated a response. Established in 2020, the Irma Thompson Initiative assists teachers, counselors, school psychologists and administrators of color with moving expenses, housing, or other job-related expenditures. It is offered as part of a broader effort to help recruit and support educators of color moving to the area, and to promote diversity in the county and cities’ schools.

We have also collected more than $1000 for the Richmond Community Bail Fund. Data concerning pretrial detention and cash bail system demonstrates stark inequity. On a given day, nearly half a million people sit in pretrial detention, separated from their communities and unable to live their lives despite not being convicted of a crime—all because they are unable to pay for the privilege of awaiting trial at home. The cash bail system contributes to the prison industrial complex and does irrevocable, long-term harm. When you take into account Black men ages 18-29 receive significantly higher bail than all other ethnic and racial groups for comparable offenses, the consequences are staggering. The Richmond Community Bail Fund works to help those a system has failed.

While we have opted for donation, there are many ways to respond to this crisis. We have included links below if you would like to learn more about these organizations. Change comes when we work at multiple scales, and we have chosen to respond at the local and state level. If you would like to learn more at a national level and find ways to get involved, we encourage you to visit blacklivesmatter.com as a place to start. And if you would like to make a donation of your own, we suggest starting with local grassroots efforts and looking for organizations that have expressed need.

Another world is possible.

Richmond Community Bail Fund (rvabailfund.org)

Rockbridge NAACP (rockbridgenaacp.com)

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

08/06/20 Are you not reading the news, Chris?

There’s nothing far-fetched about violent racism in the United States. The fact is so horrifically obvious, it’s disturbing to receive an email from an editor asking if I am aware of it. This was in February. I had just submitted a review of Ben Passmore’s graphic novel Sports is Hell. The email began with a request for revisions, followed by a page of bolded comments between my sentences.

February seems like a decade ago. CV-19 was more theory than tragedy, no states had issued executive-order lockdowns, and George Floyd was still alive.

So was Ahmaud Arbery.

So was Breonna Taylor.

Four months ago, it was unimaginable that the square in front of the White House could be renamed “Black Lives Matters Plaza” and the street-wide letters painted in fluorescent yellow down two blocks.

It was unimaginable that the NFL could declare: “We, the National Football League, admit we were wrong for not listening to NFL players earlier and encourage all to speak out and peacefully protest. We, the National Football League, believe black lives matter.”

That fact makes Sports is Hell startlingly prescient, since the take-a-knee controversy was the novel’s inspiration.

I’d tried to describe the tone of Passmore’s parody accurately, but there’s a gulf between cartoon reality and actual reality.

I wrote: “a man carrying a We The People sign is trying to catch a bus to a Black Lives Matter protest. Seems plausible enough, until a couple at the bus stop start talking. First, the white woman asks the black stranger if he wants some money, and then her boyfriend exclaims, ‘We love black people!’”

But outside of the novel’s fictional context, does that sound implausible?

I wrote: “The tone is already farcical”

Yet a summary of the novel might sound disturbingly real and not farcical at all.

I wrote: “The ambiguous merging of political protest, pointless vandalism, and football party seems about right too—but would a protest organizer really start shouting for the city to unite behind the leadership of Birds wide receiver, Collins?”

Yes, if he were viewed symbolically like Kaepernick.

I wrote: “Of course the police soon open fire on the unarmed crowd, but Passmore doesn’t plunge into full farce until the Nord Football Club for Racial Purity starts shooting too, followed by the Holy Nation of Second-String Quarterback Sherman Muck.”

Of course police have been violently dispersing crowds long before the George Floyd protests started.

I wrote: “the white characters are on the receiving end of most the humor.”

Which is appropriate. My editor suggested I read Reni Eddo-Lodge’s Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race.

I responded in an email: “Clearly I didn’t adequately describe in words the VISUAL tone that Passmore creates. The graphic novel IS unquestionably farce, though I accept that my verbal description didn’t convey that to you. I am indeed deeply aware of everything you listed (though, no, the four students who died at Kent State fifty years ago were not shot by riot police but members of the National Guard, and the scene Passmore draws is nothing even remotely like that in either tone or substance) but I appreciate your editorial concerns.”

I made the changes.

The problem was mostly miscommunication. An image tells a very different story than a sentence, and Passmore’s images are darkly cartoonish. Like any cartoon, they are simplified and exaggerated. His white characters are distorted caricatures reflecting an accurate critique of U.S. race relations. That’s the point.

But the miscommunication was mine.

I’m a white writer. I don’t get to be anything but precise when writing about race because I don’t have the right to the benefit of the doubt. My editor assumed I was suffering from garden-variety liberal racism. And that’s a fair assumption. If I want someone to not assume that, I need to demonstrate that it’s not true. I can’t expect it as a default setting. Just the opposite. If the topic is race, readers should second guess me, and I should work twice as hard knowing that.

So I’m lucky to have a good editor.

Here’s the review at is appeared a thousand years ago in February:

“I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color,” said 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick after not standing for the pre-game national anthem for the first time in 2016. “To me,” continued Kaepernick, “this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way.”

Kapernick’s fictional counterpart in Ben Passmore’s graphic novella Sports Is Hell is less eloquent. When asked by a reporter, “Do you intend to kneel during the national anthem, despite many people calling it disrespectful?” Birds wide receiver Marshall Quandary Collins simply answers, “Yes.”

Passmore’s sportscasters (who have logos for heads) call that single response “inflammatory.” Collins seems anything but.

Passmore draws oversized beads of sweat across Collins’ face. His eyes shift with every noise rising from the stadium crowd. On the field, Collins looks like a man who’s afraid he’s about to be shot. Since Kaepernick was taunted with death threats, this is one of the least farfetched things about this apocalyptic parody of racism in the US.

Passmore’s Sports Is Hell is about football in the sense that Melville’s Moby Dick is about seafood. Which means there’s plenty of football, including Collins’ Super-Bowl-winning touchdown reception. There’s also a later post-penalty reenactment performed at gunpoint in the courtyard of an all-white condo complex while militias battle in the burning streets. As one of Passmore’s anarchist characters explains: “Football teams are just a stand-in for identity.”

Despite the cover image—a weapon-toting football player standing in a field of skulls and debris—Passmore begins the novella with a few roughly realistic vignettes that imply that the story world is our world, only slightly more so. Children shoot pretend guns in the street until a bowtie-clad neighbor scolds them. But with his warning he points at a police car and says, “You don’t play with them. If you point something at them make sure it’s real.”

A page later, a man carrying a “We The People” sign is trying to catch a bus to a Black Lives Matter protest. A white woman asks the black stranger if he wants some money, and then her boyfriend exclaims, “We love black people!”

Turn the page and we’re with a different couple in a bedroom planning for the after-game celebration. Only they’re packing hammers and spray paint in hopes of a literal riot, not that “dusty nonviolence shit” of Black Lives Matter.

Though the tone is already moving toward farce, the ensuing riot begins realistically enough, with roving street crowds and a toppled can of burning trash. The ambiguous merging of political protest, pointless vandalism, and football party seems about right too—even when a protest organizer starts shouting for the city to unite behind the leadership of Birds wide receiver Collins.

Of course the police soon open fire on the unarmed crowd. The police retreat before the Nord Football Club for Racial Purity starts shooting too, followed by another team of neo-Nazis, the Holy Nation of Second-String Quarterback Sherman Muck. Did I mention the other Super Bowl team is named the Whites?

Like most cartoon commentary, Passmore’s doesn’t suffer from subtlety. Though the cast is mostly black (all those folks we met in the opening pages get thrown together like zombie survivors in a boarded-up mall) the white characters are on the receiving end of most the humor.

Passmore’s two-tone color scheme—black and an oddly appropriate beige—reduces but doesn’t obscure the increasing gore. His characters are also only mildly exaggerated, and since their universe obeys the same basic laws of physics as ours, cartoon bullets do non-cartoonish damage to their almost-proportional bodies. Yet still, most of the cast survives.

To say the novella’s ending is abrupt would be an understatement. That’s clearly Passmore’s intent. This is just another day living under US racial dystopia. Basketball season probably won’t be any different.

Meanwhile the real-world Kaepernick still isn’t playing football even though it’s been a year since he came to a confidential settlement and withdrew his lawsuit. The lawsuit accused the NFL of colluding to prevent his being hired after he became a free agent in 2017. According to the President of the United States, Colin and other players who take a knee during the anthem are at fault: “They’re ruining the game.”

With that kind of cartoon-like reality for a national backdrop, farce may have been Passmore’s most realistic option.

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

04/06/20 Talentlessly Untalented

There’s something pleasantly perverse about an internationally acclaimed autobiographical novel centered on a supposedly “talentless” main character. The Man Without Talent was so successful, manga artist Yoshiharu Tsuge was able to retire not long after publishing it in 1986. The 1991 movie adaptation must have helped.

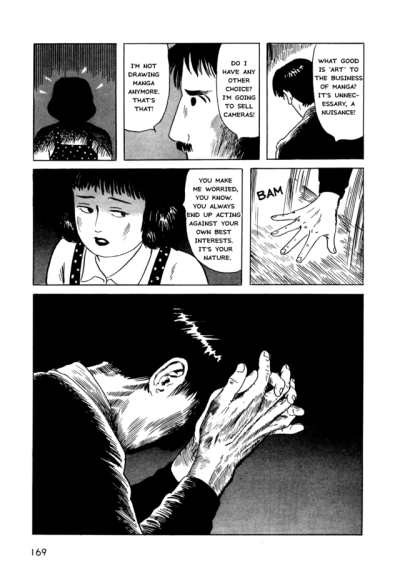

If Tsuge was anything like his Talentless narrator, comics were never his passion anyway, even during his pioneering days in the 60s and 70s. He stopped making them in 1981, but returned three years later, apparently heeding the pleas of his narrator’s wife:

“Comics are the only thing you’re good at! Please, just draw.”

Though the graphic novel has been reprinted many many times in Japan, Ryan Holmberg’s is the first English translation, and the new New York Review of Books’ edition is the first available in the U.S. Any manga enthusiast needs a copy—if only to dispel wrong impressions about the limits of the genre. Tsuge found his initial success in Garo, the same magazine that published Seiichi Hayashi’s Red Colored Elegy, which Drawn & Quarterly published in 2018 with an essay by Holmberg. His opening essay in The Man Without Talent is equally helpful, establishing the novel’s context and its autobiographical parallels.

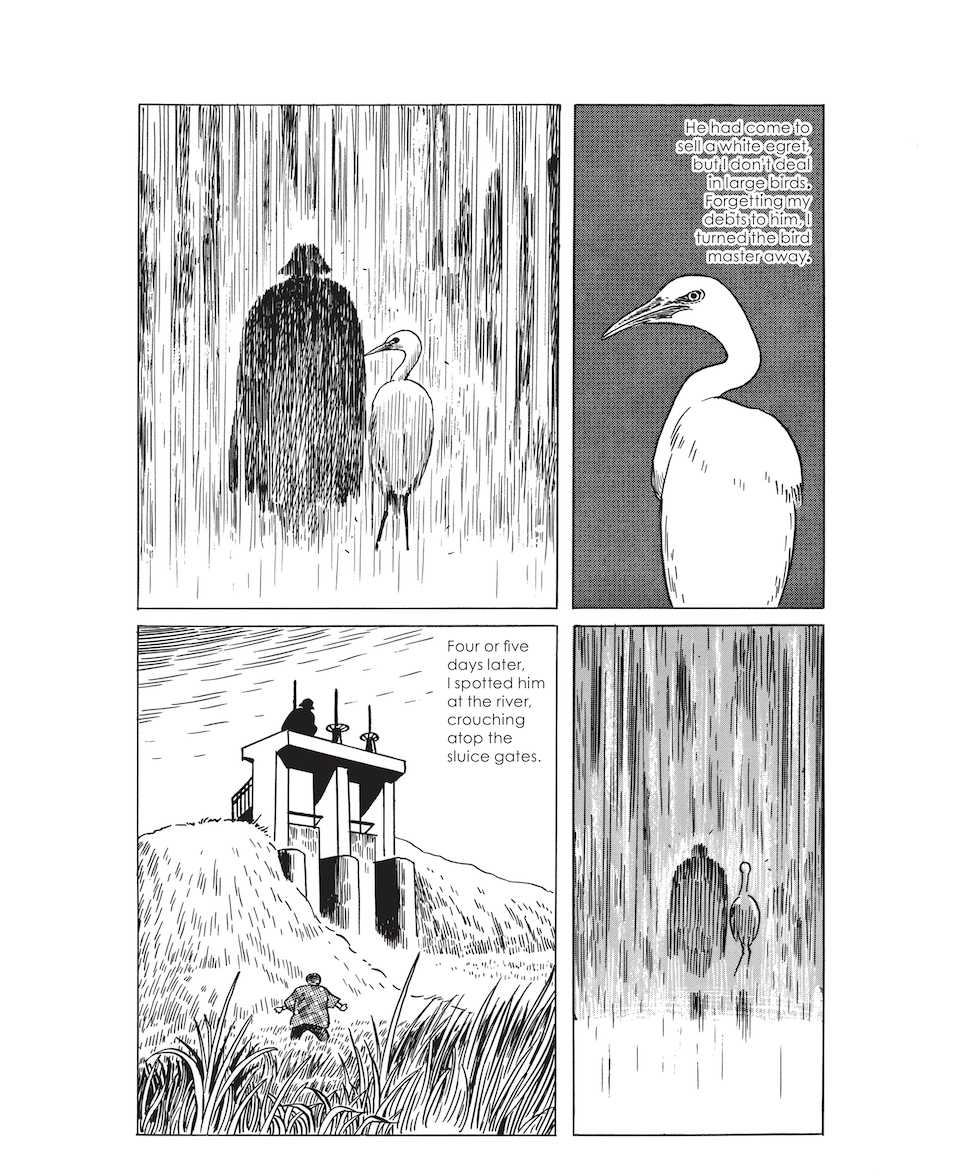

Tsuge was a leading voice in the genre of “I-novels” (Holmberg’s translation of “shishosetsu”), which offered diary-like presentations of their author-narrator’s own meandering lives. Or at least they appeared to be. Each of Tsuge’s chapters focuses on one of his hapless narrator’s failed attempts to start a business. Though Holmberg assures us Tsuge never set up a ramshackle shop beside a river to sell rocks to the occasional and deeply uninterested passerby, the Tamagawa River and its sluice gates and the town of Chofu it borders, including the Tamagawa Housing Block and the Fuda Tenjin Shrine flea market, these are all accurately depicted.

The character and the author also both enjoyed a briefly booming business repairing and reselling second-hand cameras, before the flea market supply of broken cameras ran dry. But the camera business is revealing because it actually was a success, and so not an attempt by either Tsuge or his narrator to “evaporate,” or as the lazy owner of a used book store observes to the narrator:

“It’s the same as doing nothing … you serve no purpose. Your very existence is worthless … Be useless, and society will abandon you. Thus abandoned, I practically cease to exist. Present yet nowhere, that’s me.”

Each chapter meanders into the life of one of these fellow nowhere men. The assistant to the last remaining stone expert and auction scam-artist can recite his pseudo-employer’s lectures by heart. If that’s not sufficiently pathetic, the expert wooed his wife from him first. The owner of the depressing-looking bird shop behind the velodrome sells only Japanese birds, but no “vulgar” parrots and myna that customers want. Though his business is a failure, he at least “understands what riches lie in crushing the ego.” The 19th-century poet Seigutsu literally walked away from fame, wandering the countryside in poverty until he collapsed in his lice-infested and shit-stained clothes. But like Tsuge, Seigutsu was far from talentless, and according to Holmberg, Tsuge’s homage rescued him from obscurity to join the haiku cannon.

The nowhere-man aesthetic is reminiscent of slackers of U.S. pop culture. Though Richard Linklatter’s film Slacker appeared a year before the film adaptation of The Man Without Talent, the Japenese I-novel tradition is decades older. The pseudo-autobiographical approach also has its western parallels, since the author-narrator blurring metafiction of authors like Kurt Vonnegut was making it onto best-seller lists around the time of Tsuge’s early successes.

Holmberg’s meticulously researched parallels and contradictions between Tsuge and his narrator ultimately suggest that the two are distinct, and Tsuge is only pretending to present a thinly-veiled version of himself. His narrator’s mustache is no more convincing a disguise than Superman’s Clark Kent glasses—which is the paradoxical point. “I thought,” the author explains in an interview Holmberg quotes, “perhaps I could use the style of shishosetsu to confuse fact and fiction, mislead people about what the artist is like, and thereby hide my true identity.”

Hopefully, Tsuge’s actual marriage was less horrific than the one he portrays in his novel. The wife (whose face goes noticeably unseen for the first three chapters) complains viciously, and though her criticism seems accurate, the point-of-view favors the husband, making her seem shrewish rather than suffering. The unsympathetic portrayal also aligns with an underlying misogynistic tone. The stone expert’ wife is “an easy piece of ass,” according to her ex-husband, and Tsuge draws her crotch in a revealing close-up crouch as she begins her campaign to seduce the narrator. When the bird salesman “socked” his wife after he caught her lying, he complains: “Arrested for assault. I had to eat prison slop for a week.”

The narrator is incredulous: “For a domestic dispute?”

“Even between a man and a wife, if the victim doesn’t forgive the assailant, it’s still a crime, that’s what they said. What’s the world coming to?”

It’s hard to gauge the scene, since the fact of the arrest and jail time suggest that the narrator and his fellow nowhere man are the ones out of sync with their culture and certainly its laws. But, again, Tsuge’s I-novel conceit and his narrator’s developing philosophy of Buddhist-like self-negation seem to want to place these lying, complaining, easy-ass wives outside reader sympathy. I also suspect that the presumably unintended discomfort I felt reading has less to do with cultural differences than with the three and half decades since Tsuge drew the novel. I know essentially nothing about the gender norms of early 80s Japanese culture, but I do recall early 80s U.S culture wasn’t much better than the world of the novel.

So Tsuge and Holmberg offer a much-appreciated if occasionally problematic time capsule in the form of a manga classic that is utterly unlike the teen fantasy genres that have come to define the form in the U.S. and U.K. And I predict these wandering and supposedly talentless nowhere men will continue to outlive their competitors.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Books section of PopMatters.]

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

01/06/20 Adapting Adoption to the Comics Form

Imagine finding out that you’ve been mispronouncing your own name your whole life.

Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom, author and artist of the graphic memoir Palimpsest, received her first and last names when she was adopted by a Swedish couple as a baby, but her middle name was given to her by her birth mother in Korea. It means “forest echo,” and when she heard it pronounced “Oolim” for the first time over the phone, she realized it wasn’t “harsh and ugly” at all. It probably helped that it was her sobbing birth mother saying it during their very first long-distance conversation. Sjöblom had spent her childhood and most of her adult life believing the false information fabricated by the organizations that arranged her adoption. It was only after she had her own child that she began searching for the truth.

Sjöblom’s subtitle is significant. Though Palimpsest is unquestionably a graphic memoir, “Documents from” connotes an atypical approach and aesthetic to the genre. The opening two pages feature a complete letter from a government official whom the author’s adopted father contacted for more information about her adoption. Though verbose, the official provides remarkably little.

Sjöblom includes several other similarly full- and partial-page letters throughout her narrative. Most are reformatted and typeset in the same font as Sjöblom’s narration, emphasizing that they are not the actual documents but recreations. She redraws other documents too, including an online form for “Post-adoption Services” and a hand-printed letter that she wrote herself early in her quest to find her birth mother.

One page also includes actual photocopied reproductions of two sheets from her adoption file. The sheets are critical because they contain contradictions that serve as the first clues in Sjöblom’s detective-like search. The sheets also provide the literal background of the memoir: the yellow-gray of the paper is the same yellow-gray that Sjöblom uses as the background of every panel, layering her cartoon figures and text boxes over it. Though her colors vary, all are grounded and unified in a palate inspired by those two life-changing pieces of paper.

The second half of her subtitle, “A Korean Adoption,” is equally revealing. While accurately describing her subject matter, Sjöblom’s use of the article “A” rather than the personal pronoun “My” distances her from her own story. She prefers plural pronouns, writing: “It’s no wonder we adoptees forget that we were ever born” and “Many of us actually believe our lives started with a flight.”

While this is atypical of any memoir, Palimpsest is visually unlike most graphic memoirs too. Though images accompany most of the text, their image-text relationship is sometimes purposely inexact. A woman leans over a child in bed with the talk balloon: “It was as if you’d been away on a trip and then came back to us.” On my first read, I assumed the child was Sjöblom and the woman her adoptive mother, but then I noticed that other images of what could be the same mother didn’t entirely match, especially in hair color. Sjöblom’s cartoon style is particularly stripped-down, making all of her characters generically similar, but the ambiguity seems intentional, as if Sjöblom is drawing “A” adoptive mother but not necessarily her own.

Those distancing and reading effects continue. Though she introduces her husband visually on page 17, she doesn’t refer to him by name until 41: “Rickey googles the address he finds in my Social Study, but he keeps coming back to a place which seems to be the City Hall.” A map appears below the captioned narration and a talk balloon pointing out of frame: “When I search for the address of the hospital I only end up at City Hall.” Since the previous image is of Rickey seated at a computer, if the narration were removed, little if any information would be lost. This matches Sjöblom’s generally word-heavy approach.

While I personally prefer a visual style that emphasizes images as the main force driving a narrative, Sjöblom’s emphasis on expository prose matches her purpose. Five of the six authors quoted on the back and inside covers have expertise in adoption, Asian studies, or both, while only one is a comics artist. Again, the subtitle, “Documents from a Korean Adoption,” establishes her priorities. Had she placed “graphic memoir” in the subtitle instead, readers might expect a work more deeply invested in its visual form.

Still, I wonder about the opportunities of the title. A palimpsest, as Sjöblom’s epigraph explains, is a document “in which writing has been removed and covered or replaced by new writing.” This is an excellent metaphor for adoption generally and especially the literally erased and rewritten documents that define many Korean adoptions. But it is also a visual metaphor. Sjöblom develops it in her cover image that beautifully features a child in utero, seemingly gestating inside the paper of the cover, with a thin layer of untranslated Korean words crosshatching the baby’s body.

One page of the memoir also includes a photocopied document with talk balloons over it. The interior of the balloons are opaque, so the words of the document and its text are not visible through them, but the page is still a palimpsest. Given the importance of palimpsests both literally and metaphorically to the memoir, Sjöblom might have explored the visual form beyond these two instances.

But Sjöblom does explore the minute details of her search for and reunion with her birth mother, moving from doctored documents to live phone conversations to physical reunions in the country she left when she was far too young to remember. While anyone interested in adoption should enjoy the memoir, it is particularly revealing of the abuses of the transnational adoption system that not only obscured her history when she was a child, but continued to resist Sjöblom’s attempts to find the truth as an adult.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Books section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom, Palimpsest: Documents from a Korean Adoption

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized