Monthly Archives: October 2023

30/10/23 Werewolf vs. Vampire Woman! A Halloween Comic!

I apparently made some peculiar digital art over the last few years. I blame this sequence on the pandemic. It came well after the lockdown (which really did spur some unlikely MS Paint experimentation), but it builds on the same distortion techniques. Technically each of these would be called a “photo illustration,” though I’m not sure if photo illustrations from movie stills (great oxymoron) deserve their own term, and if so, I don’t know what to call a sequence of them (except of course “comic”). Whatever the name of its medium, I titled it “WvVW” because that letter pattern is a little like the digital patterning that forms the images. It’s also an abbreviation of Werewolf Versus Vampire Woman, the 1971 B-movie public domain horror I paused and snipped the stills from — minus any actual vampires or werewolves. Each of the six pages uses the same 3×2 layout and comprises a two-character scene of wordless but implied dialogue, though the high levels of visual and narrative abstraction are the main tensions. My favorites are the first and last.

SCENE ONE

SCENE TWO

SCENE THREE

SCENE FOUR

SCENE FIVE

SCENE SIX

I’m not sure, but I may prefer some of the isolated panels. Here are my four favorites:

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

23/10/23 Trompe L’oeil & Comics Layout

I mentioned visiting the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in last week’s post, but I didn’t mention the painting that is challenging me to rethink a major segment of comics theory.

Jean Valette-Falgores’ Trompe-l’oiel Letter Board, painted ca. 1760s-70s. The VMFA curators suspect it was part of a “cabinet of curiosities.” Though that second term is tantalizing, I’m focused on the first:

Trompe l’oeil.

Valette-Falgores’s title must have been assigned retroactively, since the Met credits Louis Léopold Boilly for coining the phrase, literally “deceive the eye,” after his 1880 painting Un Trompe l’Oeil depicting a quill, coins, papers, and other items, including Boilly’s business card, arranged across a white marble tabletop.

Boilly repeated the subject at least twice more, adding playing cards to the objects and decorative wooden inlays to the table surface.

He later altered the initial conceit of relatively flat objects resting on top of a horizontal surface by depicting a vertical frame with drawings on papers variously bent and tucked into its edges and angled behind each other to resist the tug of gravity. While the earlier paintings needed to rest on flat surfaces to deceive the eye, the later painting presumably hung on a wall.

Boilly extended the range of his coinage still further by depicting live subjects – a cat and possibly himself – breaking through the surface of canvases.

That all three approaches – a horizontal still life, a vertical still life, and live subjects breaking a fourth wall – are considered trompe l’oeil works demonstrates the versatility of the term. Once coined, it was also applied retroactively to an even wider range of works, including Pompeii frescoes of simulated marble and seemingly domed ceilings in Renaissance Italy.

My interest is in Boilly’s first usage. It may be sufficient to understand comics layout.

Consider a comic that includes trompe l’oeils that match Boilly’s original: Chuck Palahniuk and Cameron Stewart’s 1996 Fight Club 2.

Stewart draws two pills as though they are resting on top of the flat horizontal surface of the page. He repeats and expands the effect with petals.

And repeatedly with flies.

If a trompe l’oeil requires the possibility of a viewer’s eyes being at least momentarily deceived, the pills could count, the flies less possibly, and the petals likely not at all. But many trompe l’oiel images fail to deceive, so the art genre seems defined less by actual deception than a perception of an intent to deceive or at least to evoke the artistic conceit of drawn content actually existing in the world of the viewer. In each case, Stewart alters drawing styles, contrasting the simplified and slightly exaggerated norms of the images depicting the storyworld with the more detailed and unexaggerated style of the realistically rendered object.

The seemingly three-dimensional images also seem to originate from the storyworld (the pills are the anti-psychotic medication the main character takes to treat dissociative identity disorder, the petals fall from a bouquet he carries), merging the art-historical category of trompe l’oeil with the literary critical category of metafiction. Though similar, the two are distinct and in some sense opposite. Metafiction breaks the illusion of its reality by drawing attention to its content’s fictionality. A trompe l’oeil instead fortifies the illusion of its reality by disguising its content as actual.

While Stewart’s pills, petals, and flies belong to the same category as Boilly’s coins, cards, and quills, Stewart’s other images may too.

Consider this pair of insets:

While the content of the insets maintains the same drawing style as the other areas of the page, Stewart draws them as though placing them on top of the other images. The deception is not of the panel content (an exploding car and rioters) but of the panels as material objects. While in this case Stewart highlights the illusion that underlying image content is obscured, in other cases he does not.

The center circular panel is drawn as though on top of a page of 2×4 panels. The trompe l’oeil techniques are less obtrusive (no white gutter surrounds the circular frame which appears to obscure the edges of talk bubbles and other minor image content), but the conceit is the same.

Elsewhere Stewart includes both kinds of images on the same page:

Both the seemingly three-dimensional fly and a standard panel inset appear to obscure the architectural sketch drawn as though part of the page. Since comics panels are often drawn as though overlapping, the trompe l’oeil approach is standard:

Stewart, like any comics artist, draws panels not only overlapping but also misaligning with rectangular page edges whenever aesthetically convenient:

While Stewart’s explicitly trompe l’oiel pills and flies are atypical in the comics medium, his layouts are arguably universal: a comics page is a rudimentary trompe l’oiel depicting material panels arranged as though atop the actual surface of a page.

In The Comics Form, I describe layout as “pseudo-formal”: “an illusion of physical qualities that creates an impression of contiguously juxtaposed images within a single visual field.” I wish I’d had the art-historical knowledge to recognize that pseudo-formal conceit as a long-established genre of fine art painting. (I hope to correct that omission in a future article.)

I also call layout a “secondary diegesis,” to distinguish it from the “primary diegesis” of a storyworld. While Stewart metafictionally blurs that division, comics characters typically “are unaware of the nominal manipulability of a pair of seemingly overlapping images, just as they are unaware of the frame edges of seemingly non-overlapping images.” Viewers of course are aware of the drawn nature of panel arrangements, but those fictional depictions are usually independent of the fiction of the panel content, making the secondary fiction more difficult to identify.

Until you notice that one of the most prevalent conventions of the comics medium is a centuries-old genre of fine arts.

Tags: Cameron Stewart, Chuck Palahniuk, Fight Club 2, Jean Valette-Falgores, Louis Léopold Boilly, Trompe-l'oiel Letter Board, Un Trompe l’Oeil, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

16/10/23 My Favorite 1800 Ethiopian Christian Comic

While our smallville college took a 4-day weekend (AKA, “reading days”), Lesley and I escaped for an overnight in the comparative metropolis of Richmond. The trip included a meandering afternoon in the Virginia Museum of Fine Art, where (it should surprise no one) I viewed many paintings through a comics lens.

The most obvious first:

Ellsworth Kelly’s 1966 Four Panels: Green Black Red Blue is as old as I am. It’s a reminder that panels are physical objects, and that what we call “panels” in comics studies are only drawings of panels. Are the areas of gallery wall visible between the panels “gutters”? I’m not sure. But negative spaces are conceptually part of the artwork, and so Four Panels requires a wall of some kind, and apparently a white one is preferable. I also like the Kelly quote the VMFA curators included: “I am less interested in marks on the panels than in the presence of the panels themselves.” Sounds like comics theory to me.

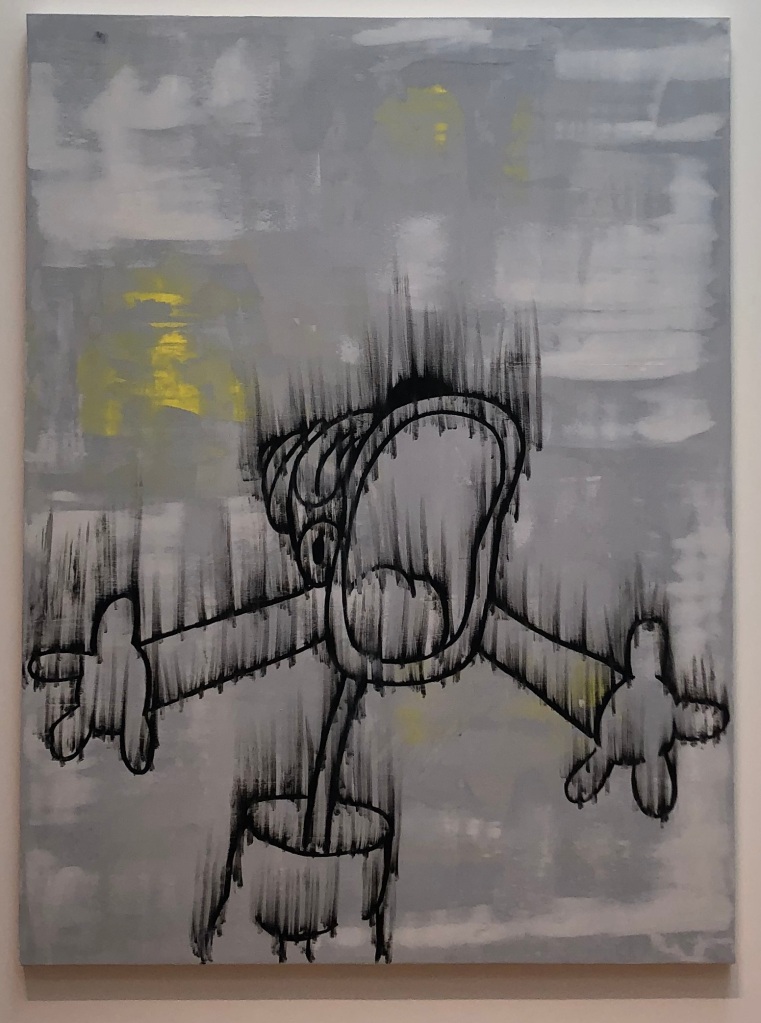

Next up, Gary Simmons’ 2020 Screaming into the Ether:

The VMFA curators say it better than I can:

I’ll just add how synchronistic it feels to be introduced to Simmons the same week I sent a final draft of my “Reading Race in the Comics Medium” to be published by the German comics journal Closure. The essay doesn’t include Basko or other Looney Toons, but it does offer a close analysis of the blackface minstrelsy drawing norms that Jack Kirby inherited from Will Eisner’s “Ebony White” and Charles Wojtkoski’s “Whitewash Jones.”

I’ve also been theorizing page whiteness in relation to racial color as part of the same book project, and so I paused a very long time over Franz Kline’s 1955 Untitled and the quotation the curators selected to hang beside it on a white wall: “People sometimes think I take a white canvas and paint a black sign on it, but this is not true. I paint the white as well as the black, and the white is just as important.”

The statement suggests so much about the apparent invisibility of racial whiteness when treated as an unchallenged norm, but I’ll dive into that another time.

Because right now I want to talk about my favorite comic in the VMFA:

It’s titled The Descent from the Cross, Burial, and Ressurection. The artist sadly is “unrecorded,” but the tempera-on-cloth painting is from Ethiopia, where the “images formed part of a larger cycle of biblical scenes lining interior walls of a church sanctuary.” The VMFA dates it “ca. 1800.”

While Simmons’ painting draws from cartooning traditions, and Kelly’s painting divides into multiple panels, I wouldn’t call either a “comic.” And not just because I avoid the word generally. I also wouldn’t say either is a “work in the comics medium” or a “work in the comics form.” But the Ethiopian sequence is definitely in the comics form (note the curators refer to the work as multiple “images,” not as a single subdivided one), and its viewing path even prefigures 20th-century comics medium norms:

Any manga fan is familiar with right-to-left viewing, though here the horizontal direction is initially secondary to the vertical top-to-bottom viewing. In comics terms, the sequence follows an N-path. More interestingly, the first direction-establishing panel (in the comics sense of the word, since the work is a single piece of cloth) is actually two images. Or rather the comics panel includes two distinct diegetic moments occurring within the same diegetic space enclosed within a single drawn frame. In The Comics Form, I call that an “embedded juxtapositional inference” (“the perception and division of a discursively continuous image into multiple diegetic images”). The two recurrent images of Christ create that perception (“recurrence” is “a quality of multiple images that represent the same subject”), and the third recurrent image in the top middle panel creates a “hinge” between panels (“juxtapositional inferencing that produces directed paths”). It’s because The Descent from the Cross, Burial, and Ressurection isn’t in the comics medium that formal analysis is necessary. Church-goers in 1800 Ethiopia presumably did not have experience with comics conventions and so would have needed to discover the painting’s viewing path themselves.

According to the curators, the images follow this sequence:

Actually they refer to the “scene of hell” ambiguously, as though it existed in some way outside of the sequence — which diegetically it does: the demonic face may be understood as an outside observer of the events depicted in the other panels. The sleeping guards are not fully sequenced either, since the events of panels 3 and 4 could occur simultaneously. That produces a variable viewing order:

That would also mean that the first two-image column is unified by spatial inferencing, and the second and third two-image columns are unified by temporal inferencing.

Whatever the viewing order, to analyze the painted cloth as sequenced images is to analyze it as a comic. Which is a problem if you are committed to the view that “comics” is an anachronistically forbidden term when applied to art created before 1890.

That’s also why I think the comics form and its various qualities might be useful concepts to apply both in and outside comics studies. If I write a second edition, I’ll need to include The Descent from the Cross, Burial, and Ressurection.

Tags: and Ressurection", Burial, Ellsworth Kelly, Four Panels: Green Black Red Blue, Franz Kline, Gary Simmon, Screaming into the Ether, The comics form, The Descent from the Cross, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

09/10/23 Superhero Comics vs. ChatGPT

It’s the night before I’m leading a discussion about ChatGPT at my English department’s start-of-year retreat. I’d spent the summer thinking tons about the problems it presents for creative writing, a little less so for literature-based courses like my first-year seminar “Superhero Comics.”

Since I was planning to ask all of my colleagues to experiment with it, especially what it will do with paper topic prompts for their courses, I follow my own advice and type into ChatGPT:

“5 paper topics for a literature course on comic books. Compare the first year of Superman in Action Comics to the first year of Fantastic Four. Which characters are similar and specifically how?”

Honestly, I wasn’t that concerned. I figured a course on comics was still unusual enough that a generative AI trained on the pre-2022 internet wouldn’t pull up much that was relevant or useful.

It gave me this:

“Comparing the first year of Superman in Action Comics to the first year of Fantastic Four is an excellent idea for a literature course on comic books. Here are five paper topics that explore the similarities and differences between these iconic characters:

- Character Development in Year One: Compare and contrast the character development of Superman and the members of the Fantastic Four (Reed Richards, Sue Storm, Johnny Storm, and Ben Grimm) during their respective first years. Analyze how their personalities, motivations, and relationships with each other evolve over time.

- The Concept of Superhero Origins: Explore the origin stories of Superman and the Fantastic Four. Discuss how these origin stories establish the foundation for each character’s identity as a superhero and how they reflect the cultural and societal context of their creation.

- Superheroic Powers and Abilities: Examine the superhuman abilities and powers of Superman and the Fantastic Four. Analyze how these abilities are used in their crime-fighting endeavors and how they contribute to the characters’ growth and challenges.

- Symbolism and Allegory in Early Comic Books: Investigate the symbolic and allegorical elements present in the early adventures of Superman and the Fantastic Four. Discuss how these characters represent larger cultural or political themes, such as the immigrant experience (Superman) or the scientific age (Fantastic Four).

- Influence and Legacy: Trace the influence of Superman and the Fantastic Four on the superhero genre and comic book industry. Explore how the success of these characters shaped the conventions of superhero storytelling and the creation of subsequent characters.

“To compare the characters more specifically:

Character Similarities:

- Both Superman and the Fantastic Four are groundbreaking characters in the superhero genre, created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster (Superman) and Stan Lee and Jack Kirby (Fantastic Four).

- They are all-American heroes, embodying traditional American values like justice, courage, and heroism.

- Like Superman, Reed Richards (Mr. Fantastic) takes on a leadership role within the Fantastic Four, similar to Superman’s role as a symbol of hope and justice in Metropolis.

Character Differences:

- Superman is an alien from the planet Krypton with nearly unlimited superpowers, while the Fantastic Four gained their abilities from a scientific experiment gone wrong, giving them a more science fiction-based origin.

- The Fantastic Four is a family unit, whereas Superman is often portrayed as a lone hero (with the exception of the Superman family of characters).

- The Fantastic Four often grapple with interpersonal conflicts and character flaws, making them more relatable and human in their struggles, whereas Superman’s personal flaws are usually less pronounced.

“You can explore these similarities and differences in detail in your literature course, analyzing the narrative and cultural contexts that shaped these iconic characters during their first year of publication.”

Okay, so that was not what I was expecting. Still though, mostly generalizations, not so much on specifics, ie evidence.

So I grabbed one sentence from its output, copied and pasted it into my next prompt, and added the word “specific”:

“The Fantastic Four often grapple with interpersonal conflicts and character flaws, making them more relatable and human in their struggles, whereas Superman’s personal flaws are usually less pronounced. give me specific examples from the first year of each comic”

It responded:

“Certainly, let’s delve into specific examples of interpersonal conflicts and character flaws in the first year of each comic:

Fantastic Four (1961):

- Issue #1 (“The Fantastic Four”): In the very first issue, we see interpersonal conflict between the team members. Johnny Storm, the Human Torch, initially uses his powers irresponsibly, causing tension within the team. This showcases his impulsive and reckless nature.

- Issue #2 (“The Skrulls from Outer Space”): Reed Richards (Mr. Fantastic) is portrayed as so absorbed in his work that he unintentionally neglects his fiancée, Sue Storm (Invisible Woman). This highlights Reed’s preoccupation with science and his lack of emotional awareness.

- Issue #3 (“The Menace of the Miracle Man”): Ben Grimm (The Thing) is depicted as deeply struggling with his new rock-like appearance. This physical transformation is a central aspect of his character arc throughout the series, representing a profound personal flaw.

- Issue #4 (“The Coming of the Sub-Mariner”): The interpersonal conflicts intensify when Namor the Sub-Mariner appears and falls in love with Sue Storm. This jealousy and rivalry create a significant source of tension within the team.

Superman (1938):

- Action Comics #1 (“Superman, Champion of the Oppressed”): In Superman’s early adventures, his character flaws are less pronounced. However, one can argue that his unwavering dedication to justice and his sense of moral superiority can be seen as potential character flaws, as they might make him seem aloof or self-righteous to some.

- Action Comics #4 (“Superman and the Dam”): In this issue, while Superman’s actions are heroic, there’s a hint of arrogance as he takes on tasks that no one else can handle. His belief that he alone can solve every problem may be seen as a character flaw by some interpretations.

- Action Comics #6 (“Superman, Football Hero”): In this story, Superman’s desire to fit in and experience a normal life as Clark Kent sometimes leads to clumsiness and awkwardness. This can be seen as a humanizing aspect, but it’s not a pronounced character flaw.

- Action Comics #7 (“Superman Joins the Circus”): Superman’s curiosity and willingness to try different roles, such as joining the circus, might be seen as a lack of focus or commitment in some interpretations.

“In summary, while the Fantastic Four’s early stories prominently feature interpersonal conflicts and character flaws, Superman’s character flaws during his first year in Action Comics are more subtle and relate to his unwavering commitment to justice or occasional moments of awkwardness as he tries to blend in as Clark Kent. The Fantastic Four’s flaws and conflicts make them more relatable and human, whereas Superman’s flaws are often overshadowed by his god-like abilities and moral certainty.”

Again, not what I was expecting. A lot of that is accurate, and (almost) all of it is plausible. I’d expected zilch. Which was stupid since, as I said, ChatGPT was trained on the entire internet – which includes more than a few words on the early Superman and Fantastic Four runs.

So I grabbed one of its examples and asked it to go even further:

“Action Comics #4 (“Superman and the Dam”): In this issue, while Superman’s actions are heroic, there’s a hint of arrogance as he takes on tasks that no one else can handle. His belief that he alone can solve every problem may be seen as a character flaw by some interpretations. Give me specific examples of his arrogance. What exactly does he say or do?”

It responded:

“Action Comics #4, published in 1938, is one of the early appearances of Superman, and it’s interesting to analyze the character’s evolution over time. In this issue, Superman’s character is still in its early stages, and he may come across as more assertive than arrogant by today’s standards. However, there are instances that could be interpreted as a hint of arrogance, especially when viewed in the context of later character development.

- Taking on Dangerous Tasks Alone: In this issue, Superman tackles various dangerous tasks without seeking assistance or cooperation. He does this with a sense of self-assuredness that he alone can handle anything. For example, when a dam is about to burst, Superman rushes to repair it without asking for help or informing authorities.

- Self-Promotion: Superman also displays a tendency to self-promote. In the comic, he leaves a calling card at the scene of his actions, identifying himself as “Superman” and declaring that he’s available to help others. This can be seen as a form of self-aggrandizement, as he assumes that people will recognize him and know that he’s the only one who can save them.

- Confidence in His Powers: Superman’s confidence in his own powers can be perceived as arrogance. He seems fully assured that nothing can harm him, and he takes risks that others wouldn’t dare. For instance, he dives headfirst into a pool of molten metal to save a man without hesitation, confident that he won’t be harmed.

- Interrogating Criminals: Superman often uses his strength to interrogate criminals forcefully. While this can be seen as a means to an end, his approach can be interpreted as a bit arrogant, as he uses his powers to intimidate others into revealing information.

“It’s important to note that these actions and attitudes are characteristic of the early Golden Age Superman, who was still evolving as a character. Over time, writers and creators have added depth and complexity to Superman’s character, addressing some of these early traits and portraying him as more humble and self-reflective. In modern interpretations, Superman is often depicted as a symbol of hope and inspiration, with a greater emphasis on his moral character and sense of responsibility.”

Now things are getting wonkier. The events described do occur in the first year of Action Comics, but not in issue #4. If a student turned in an essay making those clams, it would not go well for them.

ChatGPT also made no attempt to quote exact words or describe the visual content of specific panels. That’s what counts as evidence in my course.

But the ability to produce plausible paper topics and thesis statements is impressive — in a very not good way since one of the goals of my course is to promote original thinking.

So here’s my counter-approach for devising topics and arguments in my first-year writing seminar.

ChatGPT is very good at producing generalizations. Reverse the process with specifics-first drafting:

STEP 1: Isolate an interesting detail and write about it.

I’ve always had my WRIT 100 students write a page of analysis and interpretation for every reading assignment. The instructions are basically: notice interesting things and talk about them. Even better, I tell them to write how they actually write–informally and don’t worry about grammar, etc. Both aspects are key for our suddenly ChatGPT-world. My other literature courses select passages from each reading and write questions about them so they’re ready to lead discussion on a topic that personally interests them. Again, it’s almost like I was trying to circumvent ChatGPT all along.

STEP 2: Discover other similar details.

Having already found something that interests you, keep an eye out for more of it. Maybe it’s something about a character’s motivation, maybe it’s a visual motif, doesn’t matter — once you’ve found something specific, related specifics tend to follow. Our brains become attuned to them. Sometimes I have students write a sentence or two about possible paper topics each night, building on their previous observations. Sometimes they list two or three pages with related passages. Identifying patterns and making lists — that’s called thinking, and that’s something ChatGPT can’t do.

STEP 3: Develop a claim about that detail pattern.

What claim? Let the specifics tell you. Look at a passage and ask yourself: if this appeared in an essay, what would it be used to prove? What do the passages have in common? Where do they diverge? What subcategories could you place them in? Those might become body paragraphs. The trick is to build up from the evidence. The argument is already there. You just need to state the connections.

Are those steps ChatGPT-proof? Probably not. But it’s a good start — one that reminds me why writing is such a relevant skill. It’s not about putting one word after another. It’s about thinking through ideas. That’s still the superpower I’m teaching.

After drafting the above, I created a more nuts-and-bolts set of instructions to implement in my classroom. Here’s what I gave my students:

Begin with a specific passage/image that intrigues you and ask: If this were in an essay it would be evidence to support what claim? That’s your hypothesis.

Search for related passages/images and list them. Apply the same question. Is there a unified pattern? Are there subcategories? Are there disagreements? Progressions of change? Adjust your claim.

Search the second work for related passages/images and list them.

Ask how the claim from the first work applies to the second work: Are the two in agreement, disagreement, or partial agreement? That’s your thesis.

Complete this Process List and submit it as the final page of your rough draft:

- First passage/image:

- Hypothesis based on the first passage/image:

- List of related passages/images:

- Adjusted claim based on list:

- Hypothesis for how the claim from the first work might apply to the second work:

- List of related passages/images from the second work:

- Combined thesis for both works:

As usual, I met with each student for twenty minutes to discuss their draft, drawing from their Process List as needed. An unexpected perk: when an argument got too generalized, there was often something more specific in the Process List (especially #2) that could be reinserted.

I’ve not read all the final drafts yet, but so far I like the revised process — not because it works around ChatGPT, but because it helps students develop better essays.

Which, of course, is the same thing.

Tags: Action Comics, ChatGPT, Fantastic Four, Jack Kirby, Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster, Stan Lee, Superman

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

02/10/23 Why the YA graphic novel “Kiss Number 8” should not be removed from my town’s middle school library

If you’re going to join a call to have a book removed from a school library, you should do your homework first. That means reading the book – all 305 pages, not just the one and a half pages someone else photocopied and distributed in a letter of complaint addressed to the community.

The library is Lylburn Downing Middle School’s in Lexington, VA, and the book is the YA graphic novel Kiss Number 8 by Colleen AF Venable and Ellen T. Crenshaw. It’s about a teen named Mads. She’s a Christian. Readers know she’s Christian beginning with the front flap: “Mads is pretty happy with her life. She goes to church with her family and minor league baseball games with her dad.”

The church-going is shown early and often, including near the end, when her problems are at their worst. She never stops going to church. Though she’s angry with her mother early on, by the end they have grown close, and they attend church together through every phase. Church is portrayed as an unquestioned positive constant in her life.

Mads also talks to God regularly when outside of church. Early in the novel when she worries that her father might be having an affair (he’s not), Mads asks God: “I know you forgive, so whatever Dad did, I should just forgive him, right?” And late in the novel when she’s anxious about changing schools, she continues to address God in her thoughts: “If you feel like tossing me any advice …”, adding after she bumps into someone: “Advice received: Stop inner-monologuing in crowded entryways.”

It also doesn’t take an especially observant viewer to notice that Mads is clasping her cross pendant on the front cover. She is a Christian beginning to end.

And yet the author of the letter of complaint says that “just because my beliefs and values are traditional, does not mean they don’t deserve acceptance and protection too,” adding that she hopes “if your religious beliefs were so badly offended by my school, I would come to your aid,” before calling on “all people of faith to stand against this debasement of my religious symbol and reality.”

Does Kiss Number 8 debase Christianity? Has the middle school badly offended Christians and all people of faith by making the novel available in its library?

The accusation rises from a single page, one of the one and a half attached to the letter of complaint. In that first church scene, Cat, one of Mads’ friends, says: “You can’t deny that he’s totally hot. I mean, look at those abs.” At first it looks like Cat means the altar boy, but Mads asks: “So, you’re telling me you go to church because you have the hots for Jesus?” Cat answers: “Noooo. I have the hots for THAT SCULPTURE of Jesus.” When Cat imagines that the statue has “an ass that could crack a walnut,” Mads responds: “Ewwwwwww.”

Mads’ response is key. Readers identify with her, the narrator, not with Cat, someone just now being introduced. Mads’ “Ewwwwww” cues the reader’s Ewwwwww. We are supposed to be grossed-out.

To make that more explicit, Cat turns out to be the villain of the story, and her gross introduction is the first step in establishing that. She is also the novel’s most sexualized character, pressuring Mads not to be “prudish” and typing the other bit of dialogue included in the letter of complaint. The writer of the letter said that she does “not give teachers license to educate my child so cheaply on gender choices, sexuality, or sex.” Setting aside that the novel was not part of any teacher’s assignment, the authors of Kiss Number 9 would agree. Cat is the novel’s foil, a model of how NOT to be.

The writer of the letter of complaint doesn’t mention that Cat is also the most anti-gay character. When Mads’ bisexuality is revealed, Cat literally vomits. She later yells: “Tell me it’s not true. […] I’ve been going around like an IDIOT for months defending you, swearing to people you ‘aren’t gay, you’re just picky.’” When Mads answers, “I’ve had a crush on you for years,” Cat scowls, stomps away, and seals an EXIT door between them with a violent kick. It’s one of the only wordless pages in the novel. They never speak again.

Cat, the villain, is anti-gay, but Kiss Number 8 is not anti-gay.

Cat, the villain, is irreligious, but Kiss Number 8 is not irreligious.

How does Mads feel about church through all of this? She says: “But I still went to church every Sunday with my Mom. If she was secretly praying for me to be ‘cured.’ She never let on. Me, I just prayed for God to tell my mom that it’s okay. Weirdly enough, church was one of the only places I FELT okay.”

An offensive debasement of religion? People of faith should read and judge for themselves.

- My town has two newspapers. I sent a version of the above letter to the monthly, and this next letter to the weekly.

The LDMS administration has begun banning books from its middle school library, starting with the novel Kiss Number 8, because a parent made the vile accusation that the school is “grooming” children.

The novel is about a teen discovering that she’s bisexual.

Parents should make decisions about their own children, not about other people’s children. If a parent doesn’t want their child accessing books, they should follow current school policy and submit a letter indicating that. But it is unacceptable for a parent to make parental decisions for other children by removing books to satisfy their personal preferences.

This novel is the first target. The complaining parent claimed the library is “flooded” with books she personally thinks would “irrevocably harm” her children, and she wants the school to “investigate” and create “an open review” so parents can force the removal of more books.

She also demanded “an open review of the process” – and I agree. It is unclear why the administration removed the book or what criteria will be used in the future.

Defining middle-school appropriate books should be simple: Did a reputable professional publisher designate it to be appropriate for middle-school readers? Did reputable professional reviewers or award judges confirm it to be appropriate for middle-school readers? Did a reputable professional librarian select it for middle-school readers?

Any other questions are about private preferences that cannot be allowed to determine what is or is not generally available in a school library.

- Sadly Kiss Number 8 is not the only book being targeted. So I also wrote to the school board chair last week.

Though recent focus has been on Kiss Number 8, with additional attention on It’s Perfectly Normal, and how both books appear to have been removed in violation of policy (“A review committee consisting of the principal, the library media specialist, the classroom teacher (if involved), a parent and/or student, and the complainant will convene”), I’m writing about the list of additional books that appear to be the next targets (based on the attached flyer from the Rockbridge Area Republican Committee facebook page):

That list includes This One Summer (which, like Kiss Number 8, I’ve read). According to the publisher, the graphic novel is appropriate for ages 12 and up: Macmillan.

If my understanding of the current system is correct (YA books are marked “YA,” and parents who object to YA books can prohibit their children from accessing them), then I see no need for any change – and therefore Kiss Number 8 should be returned to the library.

However, if the board decides to adopt some new policy, please make it one that is not bendable to any individual’s personal opinion/preference – including any administrator’s. Determining age-appropriateness should be a simple and verifiable process. In the case of This One Summer, there is no room for confusion: it’s for readers age 12 and up. If any parents object to its content, they should be able to prohibit their children from checking it out; they should not be able to prevent other children from checking it out by having it removed from the library. This could cut both ways: parents who prefer YA books identified for 9th grade and up to be available in the LDMS library would have to accept their being removed.

I strongly prefer the current system: marking novels “YA” should be enough.

But whatever happens next, please do not allow This One Summer, It’s Perfectly Normal, or any other book verifiably age-appropriate for middle school readers, to be targeted and removed based on individual preferences.

Tags: book bans, Colleen AF Venable, Ellen T. Crenshaw, kiss number 8, this one summer

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized