Monthly Archives: October 2021

25/10/21 Judicial Retconning IV: A Retcon By Any Other Name

Though the word ‘retcon’ is relatively new to the U.S. legal system, the process of retconning is not. That law professor friend of mine recently emailed me about a pair of articles: “Had to copy and paste these for you when I read them: my colleague’s retcon account of unconstitutional laws, which one would never find by search for ‘retcon’ or cognates. You’re right—we’re all retcons now.”

In his 2008 Georgetown Law Review article “The Executive’s Duty to Disregard Unconstitutional Laws,” Saikrishna Bangalore Prakash coins the term ‘Citizen Disregard’ as a subset of civil disobedience. A citizen “may choose to defy all manner of statutes that they believe are unconstitutional,” claiming such a “statute is no valid law at all and hence her actions were not unlawful.” If “a court concludes that the underlying statute is constitutional, the private citizen will be found guilty,” but if the court agrees, the citizen is not guilty—revealing that the apparent law was never an actual law. It was just mistakenly understood to be one by people other than the citizen disregarder.

Such a decision is a retcon. It reveals how things actually were all along. If the decision were a sequel, then the citizen disregarder would have been guilty of breaking the law while it was still a law, but then not punished because the law was struck down by the court during the subsequent trial. The sequel v. retcon distinction is less a disagreement about constitutionality and more about reality. Was a law a law before it wasn’t a law or was it never a law at all?

Prakash adds in his 2020 Harvard Lew Review “Faithless Execution” that citizen disregard retcons are independent of the judicial decision: “the American tradition has been to conclude that … some ‘acts’ are unconstitutional, and are therefore nullities, without regard to whether a court has so declared.” This further distinguishes the retconning from sequels, because sequels are created by new actions. Though retcons require revelations to be recognized and then applied, their logic requires that any revealed reinterpretation was always true and would be true whether revealed or not. The court does not make the statute a nullity. It discovers that the statute was always a nullity.

The Supreme Court’s 1886 Norton v. Shelby County decision makes the retroactive nature of a judicial retconning explicit: “An unconstitutional act is not a law … it is, in legal contemplation, as inoperative as though it had never been passed.” The case determined that bonds signed by a county commissioner were not valid because, despite a sequence of individuals appearing to serve as county commissioners for the two decades, the county never had a commissioner. They just thought they did. The Court explained: “As the act attempting to create the office of commissioner never became a law, the office never came into existence. Some persons pretended that they held the office, but the law never recognized their pretensions.” The court called them “usurpers.”

In his 1962 article “The Retroactive Effect of an Overruling Constitutional Decision: Mapp v. Ohio,” Paul Bender explores the practical ramifications of such court-discovered usurpers. The Supreme Court ruled in 1961 that Cleveland police officers who broke into Dolly Mapp’s home without a warrant had no legal right. Mapp was dating a Cleveland racketeer, and the police found a suspect in the bombing of a rival racketeer’s home hiding in her basement. They also found gambling slips and pornography. Mapp was acquitted of the gambling offense, but after she refused to testify against her boyfriend, she was sentenced for the pornography. By declaring the evidence inadmissible, the Supreme Court freed Mapp and also reversed its 1949 Wolf v. Colorado decision, which had instead determined that the prohibition of illegally-seized evidence did not apply to state courts, upholding the conviction of Julius Wolf for “conspiracy to perform an abortion.”

Bender calls the “sudden change of law” produced by Mapps “an unorthodox exercise of judicial power” that creates a “problem of retroactivity” about “which rule applies when trials predating the announcement of the new exclusionary rule are now challenged.” Though he makes an extensive argument for what he calls “a somewhat arbitrary line excluding most previous trials,” Bender also acknowledges that “the only logical choice would be complete retroactivity.” That’s because Mapps is a retcon, not a sequel. While content that the decision applies to all future cases, he seems uncomfortable with its also being retroactive. (In the language of my previous posts on judicial retconning, Bender thinks Mapps is a Klingon butthead.)

Bender may be correct that “the purposes of the new rule do not call for general reexamination of previous convictions,” but any reexamination of a conviction based on evidence that is retroactively revealed to have been inadmissible must be overturned. While Mapps does not “call for a general reexamination”—which presumably would involve a review of all cases to identify those that involved inadmissible evidence—it does not bar it either. It does, however, require that if such a conviction is examined, it must be overturned.

Bender’s use of the word ‘announcement’ is revealing. Mapps announced “the new rule exclusionary rule,” and so in the logic of retconning which Bender acknowledges, it did not create the rule. The newly discovered rule applies to all trials regardless of when they occurred. The announcement itself did not do anything—except for Dolly Mapps. If other wrongful convictions are to be overturned, each must be brought before a court too.

This is true of retcons generally. The announcement of the new discovery of Neptune in 1846 did not alter any astronomy textbooks. That required a separate and protracted process of its own. Bender’s question of applicability is akin to an astronomer asking whether the existence of Neptune should be applied before 1846 or only afterwards.

Bender also cites the Supreme Court’s 1940 Chicot County Drainage Dist. v. Baxter State Bank, which expresses a similar discomfort with retconning and a preference for sequels. The decision reversed a lower court’s application of the Shelby logic to a bankruptcy case: “The courts below have proceeded on the theory that the Act of Congress, having been found to be unconstitutional, was not a law; that it was inoperative, conferring no rights and imposing no duties, and hence affording no basis for the challenged decree.” This time the Court rejected that retconning logic: “The actual existence of a statute, prior to such a determination, is an operative fact and may have consequences which cannot justly be ignored. The past cannot always be erased by a new judicial declaration… a principle of absolute retroactive invalidity cannot be justified.”

Chicot incorrectly relies on the logic of sequels. A retcon does not erase the past—it reveals it. The past is neither justified nor unjustified—it is whatever it is, however convenient or inconvenient. If past facts were previously misunderstood, the mistaken account is invalid. Referring to “a new judicial declaration” that erases the past implies a kind of sequel. Things were one way, and now they are some other way. Shelby and Mapps instead establish that nothing actual has changed. Stating that the unconstitutional statue had “actual existence” would require that it had been previously constitutional—otherwise it was never an actual statute. The plaintiffs in Shelby argued the county commissioners “were officers de facto,” which means “in actual existence,” a principle the Court absolutely rejected.

The disagreement between the 1940 Court and 1886 Court is the nature of judicial revision. Do retroactive decisions change the past or reveal the past? The jury may still be out.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

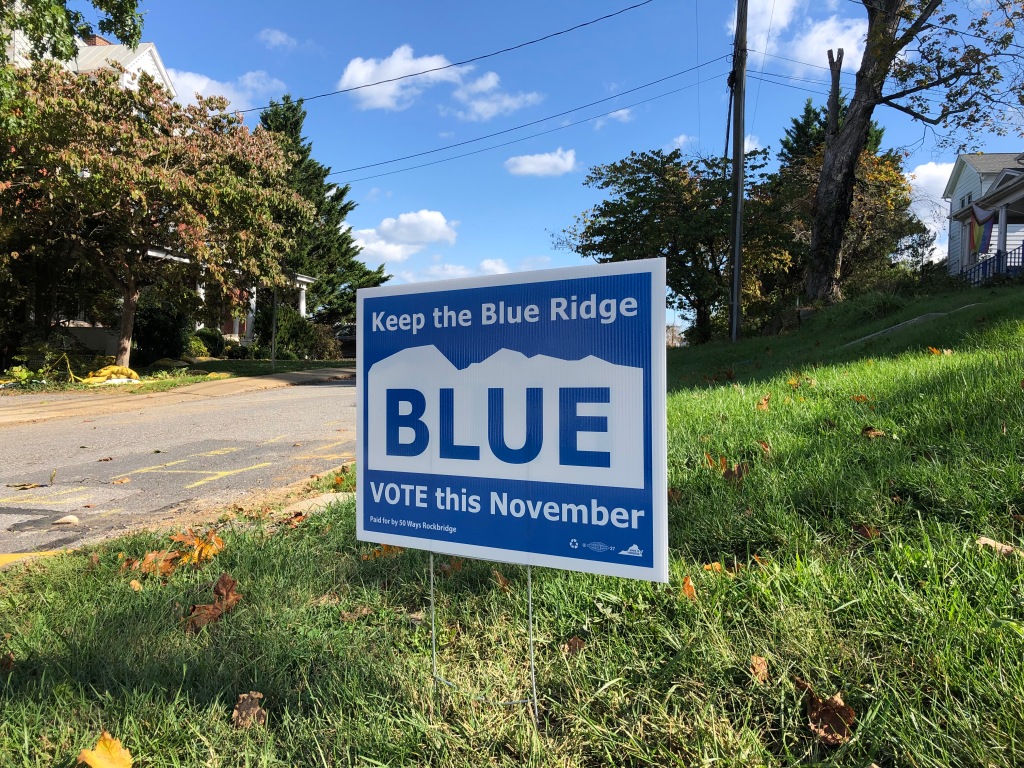

18/10/21 Is This a Comic?

The short answer: probably not.

It’s a yard sign for a local grassroots get-out-the-vote campaign. It’s not something published by a comics publisher. That’s my circular but still useful shorthand definition of the comics medium. The comics medium is distinct from the comics form, which I can define in even fewer words: sequenced images.

So if the yard sign contained two sequenced images, would it be a comic? Well, if being a work in the comics form is enough for something to be a comic, then yes. But does the sign contain two images?

That’s going to require the long answer.

For the sign to be sequenced images, it has to include at least two images. If you look closely at the bottom right corner, there are three small images (including a recycling symbol and the outline of Virginia). Because they are so small, and so secondary to the larger design elements, I’m going to ignore them. That leaves seven much larger words and the central white area. If you call the word “BLUE” an image and if you call the shape framing “BLUE” an image, then the sign has two images.

But should we call either an image?

I’ve written previously about how the way a word is rendered can make it word-image art. In this case, does the way “BLUE” is rendered make it art? I suspect there’s room for debate, but my instinct says no. Its graphic-art qualities seem much less operative than its linguistic qualities.

That would mean the sign includes (at most) one (significant) image, and since one image can’t be sequences images, the sign isn’t in the comics form, and since it’s also not in the comics medium, it can in no sense (that I know of) be considered a comic.

But, what the hell, let’s say “BLUE” is word-image art (its size and color are the sign’s most distinctive qualities) and so an image. Then is the white space framing it an image too?

This is a variation on a question I’ve been chewing on while completing my next book manuscript, The Comics Form: The Art of Sequenced Images. The last chapter is titled “Sequenced Image-texts.” Though a comic (whether defined by form or medium) doesn’t have to include text, many do. So understanding how sequenced images work requires understanding the subset of sequenced image-texts. And that requires determining the minimum necessary qualities for an image to be an image.

Here’s a bit from the draft:

In traditional comics, hand-lettered or typeset words appear in frames termed ‘caption boxes’ and ‘balloons’ or ‘bubbles’ distinguished by the linguistic content of speech or thought, with ‘tails’ or ‘pointers’ directed at rendered subjects. The framed words typically divide into lines according to the discursive requirements of the frame and so with little or no linguistic consideration, but word frames can also produce units and rhythmic effects similar to lines or stanzas of poetry. The backgrounds of framed areas are sometimes different from the surrounding image, often with the same white negative space as margins and gutters. Since these frames, like drawn frames generally, are not actual frames but representations, words in word frames are image-texts, with the non-linguistic elements communicating meaning. Pratt, for example, observes that “word balloons may also, through their style or even color, give pictorial cues to the reader as to the mental states and attitudes of their utterers” (2009: 110).

If a frame and words are sufficient to make an image-text, then many PowerPoint presentations are in the comics form, including the story “Great Rock and Roll Pauses” in Jennifer Egan’s 2010 A Visit from the Goon Squad, which is a PowerPoint both discursively and diegetically since it is created by a character within the story. Many charts, graphs, and diagrams are image-texts too, and so would combine in the comics form. Alternatively, such example might be excluded from the comics form if non-linguistic images must display some minimal level of graphic-art quality to produce image-texts in combination with word-images. Such a spectrum would be subject to individual perception.

In other words, I’ve been thinking:

Now back to the yard sign: does the shape framing “BLUE” have enough graphic-art quality to be called an image? Here my instinct says yes. Though the bottom and side edges are single lines, the top edge consists of sixteen lines. The top edge is also representational: it represents the Blue Ridge mountains. Since representational images are a kind of image, they presumably have “some minimal level of graphic-art quality.”

But what if viewers don’t perceive the top edge as representing a mountain ridge? If those viewers don’t read English, they would not have the linguistic cue, and maybe the row of varyingly angled lines would be too abstract to evoke anything by itself?

I could always cheat and invoke authorial intentions. Which in this case would be my intentions. I drew those sixteen lines along the top edge of the rectangle to resemble a mountain ridge when drafting a possible campaign sign after a candidate dropped out of our local town council race last year. We wanted someone to jump in, and for a horrible moment I was considering being that someone:

I decided not to run, but when our grassroots group wanted a yard sign for this November’s election, I was happy to repurpose.

Which is a long way to say that I see a mountain ridge in the angles of the top edge. But I’m just one viewer (who happens to have unique knowledge of the creative process, including the creator’s intentions). Since perception is individual, the same object may be an image to one viewer and not an image to another viewer. Since the sign includes two elements (“BLUE” and the top edge of the white area) that seem to fall in the ambiguous middle zone of the image or not-an-image range, the sign may be perceived as containing no, one, or two images. The first perception would make it simply text (though apparently with some non-linguistic yet sub-image flourishes). The second would make it an image-text. And the third would place it in the comics form.

So is it a comic?

Like I said, probably not.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

11/10/21 Judicial Retcons III: The Return of the Klingon Buttheads

Retcons have entered U.S. law. They’ve also entered U.S. law studies—as a law professor friend of mine recently showed me after running a search for the term in law review articles. He found three.

In his essay “The Employment Status of Ministers: A Judicial Retcon?,” Russell Sandberg writes: ‘“Retroactive continuity”, often abbreviated as “retcon”, is a term often used in literary criticism and particularly in relation to science fiction to describe the altering of a previously established historical continuity within a fictional work.’

So far so good—especially if you consider superhero comics a SF subgenre. He continues: ”To date, however, the concept has not been used in relation to law.’

Sandberg published his Religion & Human Rights article in 2018, and the first use of ‘retcon’ in a court ruling is 2019, so still good. He continues: ‘Legal judgments often refer to history and include historical accounts of how the law has developed. Such judgments invariably include judicial interpretations of history.’

Yep, that’s a good working definition of ‘judicial retcon.’ But then Sandberg writes: ‘On occasions, they may even include a “retconned” interpretation of legal history – a “judicial retcon” – that misrepresents the past and rewrites history to fit the “story” of the law that the judge wants to give.’

No. That’s not a retcon—that’s a rejected retcon since it is identified as a misrepresentation. Worse, Sandberg suggests codifying his definition of ‘retcon’ into legalese: ‘This article explores the usefulness of a concept of a “judicial retcon” by means of a detailed case study concerning whether ministers of religion are employees.’

Setting aside minsterial employment minutia, the case is another Klingon butthead, or lame attempt, as discussed in earlier posts. Instead of discussing the general phenomenon of retconning in court rulings, Sandberg isolates an example that he feels is a false reinterpretation of historical precedents and uses it to define ‘retcon’ generally. By his definition, all retcons are bad retcons. But all judicial interpretations of history fit the “story” of the law that the judge wants to give.

Sandberg also doesn’t get credit for first author to use ‘retcon’ in a law paper. Dan L. Burk’s “The Curious Incident of the Supreme Court in Myriad Genetics” appeared in the Notre Dame Law Review in 2014. Burk’s use of ‘retcon’ is more complex.

He writes: ‘whatever such cases originally meant or perhaps now should mean, the Supreme Court has repeatedly relied upon them to justify and shore up the products of nature concept. Throughout its cases on subject matter, the Court has in particular “retconned” Funk Bros. as the go-to citation for the Chakrabarty dicta on products of nature. In Myriad, Justice Thomas reviews Funk Bros. at some length, concluding that the treatment of the Funk bacterial inoculum serves as squarely analogous precedent for the treatment of Myriad’s genomic sequence. Thus, notwithstanding its actual holding, the case seems to have undergone hindsight reconstruction as a decision about the patentability of natural products. Thomas uses this to provide a veneer of precedent for the Court’s holding on gene patents.’

There’s a lot to close read there. The tone is overall neutral and perhaps accepting of the ruling. Though the adjective “curious” in the title (and the allusion to a detective novel about a narrator with autism) is at best ambiguous. The adjective “hindsight” shuffles further toward negative connotation. And “a veneer of precedent” is a mild-mannered outburst of carefully passive aggression. Justice Thomas is, after all, Justice Thomas, and the Supreme Court ruling in question is the currently definitive ruling on the topic. Rereading Burk’s first phrase, his resistance to retconning is present there too, since “whatever such cases originally meant” suggests an unrevisable first meaning linked to the later “actual holding,” and “or perhaps now should mean” suggest a distinct change in meaning and so a sequel.

So Burk knows he can’t reject a Supreme Court retcon, but he doesn’t have to be happy about it.

‘Retcon’ appears in only one earlier law review essay, Jeffrey Zeman’s “The Adventures Of ‘Superman’: A Narrative Worth Mediating,” published in Conflict Resolution in 2011. He writes: ‘In comic book vernacular, this phenomenon is often referred to as “retconning” a story. “Retcon” is short for “Retroactive Continuity,” a literary device used by comic book authors to change the known history of their characters—most often superheroes. Changing one element of a character’s past can alter the significance of all of that character’s future stories. Comic book authors are especially fond of using this device when they want to resurrect a character that previously died at some point in the often decades-long archive of superhero stories under a publishing imprint.’

By “this phenomenon,” Zemans means the two-stage termination clause of the 1909 Copyright Act which “created a dual term in the copyright to a work, one realized upon the work’s publication and the second occurring twenty-eight years later with the copyright’s renewal.” The clause is included in the law because “an author’s ability to realize the true value of his or hers work was often not apparent at its creation, but required the passage of time (and the marketing efforts by a publisher) to materialize.” Zemans likens the reevaluation opportunity to transporting the parties “back to the time of consignment in order to create a more equitable contract.”

Regarding the copyright of Winnie the Pooh, Zemans writes that A.A. Milne’s heir “learned with the benefit of hindsight: that Pooh had greater value than A.A. Milne had anticipated when he first signed away his interest in the anthropomorphic bear.”

While the change in Milne’s contract would certainly reflect hindsight, is hindsight the same as time travel? Zeman says Milne’s heir “looked back at the way the story had gone” while “standing from the retrospective viewpoint of the statutorily-created termination period.” That’s not returning to the past and changing it. That’s just looking at the past. ‘Retrospective’ and ‘retroactive’ are not synonyms.

Zeman’s analysis also reveals nothing about the judicial meaning of ‘retcon’ since it applies only to the specifics of the 1909 Copyright Law and its sequel clause. That leaves only Sandberg’s rejection and Burk’s begrudging acceptance of retconning decisions. Based on the term’s vacillating use in law review articles and in previously discussed judicial decisions, the legal meaning of ‘retcon’ remains contested.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

04/10/21 When Are Words More Than Just Words?

Here is a set of words:

"Texas banned abortions after six weeks. Seven more states are copying the law. If the GOP wins in November, Virginia will be next. 'Well, I can tell you that would be me,' said GOP Lt. Gov. candidate Sears, 'I would support it.' The Virginia Senate is split. The Lt. Gov. casts the tiebreaking vote. If elected governor, Youngkin will sign it. Don't let Virginia be the next Texas. VOTE TODAY"

Here is a set of words:

Are those two sets of words the same set of words?

Yes and no.

Yes, if by ‘words’ you mean linguistic content.

No, if by ‘words’ you mean graphic marks.

Since ‘words’ are both linguistic content and graphic marks, the contradiction is unresolvable.

Which creates a problem for the definition of comics, since all definitions include the word ‘images,’ usually along with the word ‘sequenced’ (or ‘juxtaposed,’ but let’s not go down that rabbit hole right now). I call sequenced images the comics form (which is distinct from but overlapping with the comics medium), but however termed, graphic marks are images. Which means the graphic marks you are currently reading are images, and because they are also sequenced, they must be a comic (or at least must be in the comics form).

Spoiler alert: they’re not.

Explaining why they are not is complicated and requires a tool for prying apart words as graphic marks and words as linguistic content.

Look at those two sets of identical/non-identical words again. The are identical as far as their linguistic content, but they differ significantly as far as their graphic qualities. The first set is graphically formatted the way this paragraph is: all the letters are in the same font, are the same size, and are the same color. The words in the second set are also all in the same font, but they differ in size (which varies according to rows, with words in rows consisting of fewer words printed larger because each row is sized to have the same width) and in color (black or red).

Those graphic qualities may also indirectly alter linguistic content, since differences in size and the relative rareness of red gives greater emphasis to certain words, and emphasis influences meaning. Readers of each set are going to have different reading experiences due to the graphic qualities.

Since both sets of words are graphic marks, some graphic marks are therefore more graphic than others.

That claim is both true and complete nonsense.

It’s nonsense because being graphic isn’t a graded quality. The adjective ‘graphic’ is like the adjective ‘physical.’ Either something is graphic or it is not graphic.

But ‘graphic’ also refers to something that occurs in degrees. I would call that something ‘art,’ specifically ‘graphic art.’ Along the graphic-art scale, these words you’re reading right now are very low. They are still 100% graphic (because to be graphic is to be 100% graphic), but they are hardly or not at all graphic art. That’s because their graphic-art qualities are so minimal.

In contrast, the set of words in the second example are higher on the graphic-art scale. Though they are certainly not great graphic art, they still fall into the general category graphic art.

(If authorial intention matters, I can add that I made the second example in response to a request for a ‘graphic,’ one that could be shared as a social-media meme or printed as a poster or postcard. I also made the first example, which can be copied and pasted into the body of an email, with no concern about changing fonts, font sizes, or line breaks–and so no concern for graphic qualities.)

Since the second set of words consists of words that are higher on the graphic-art scale, does that mean it’s a comic?

Well, if a ‘comic’ is something that is in the comics form, and if the comics form is sequenced images, then the answer is (probably) no. That’s because I understand the second set of words to be a single image, and a comic requires at least two images. Since that concern distracts from the core question, look instead at this:

Whatever you call it, there are definitely two of it. And since I would call each an image, I would have to also call their combination to be in the comics form.

Unless each set of words is not an image. And here I mean ‘image’ to mean not simply graphic marks but graphic art or, because the art consists entirely of words, graphic word art.

So determining whether it’s a comic first requires answering this question: Where is the dividing line between words that have only minimal graphic-art qualities and so are not graphic word art and words that do have sufficient graphic-art qualities and so are graphic word art?

I have no idea.

I am confident though that the first example falls into the first category. Those words are graphic only in the sense that is akin to something just being physical.

I’m not sure, but I suspect the second example can be called an image in the graphic-art sense only if its graphic-art qualities exceed its linguistic qualities. In other words: if it’s more about how the words are rendered than what the words mean regardless of rendering.

In this borderline case, my gut votes no. The rendering primarily serves the linguistic content, and without the linguistic content, the set of graphic marks wouldn’t be sufficiently artful to be called graphic art. Though as soon as I type that opinion, I start hearing counter arguments in my head. Which gets to my next point:

Judgements will vary.

As a result, judgements about whether any particular sequenced sets of words are in the comics form will vary to the same degree.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized