Monthly Archives: October 2017

30/10/17 Science Fiction Makes You Stupid

That is a scientifically grounded claim.

Cognitive psychologist Dan Johnson and I make a version of it in our paper “The Genre Effect: A Science Fiction (vs. Realism) Manipulation Decreases Inference Effort, Reading Comprehension, and Perceptions of Literary Merit,” forthcoming from Scientific Study of Literature.

Dan and I are both professors at Washington and Lee University, and our collaboration grew out of my annoyance at another study, “Reading Literary Fiction Improves Theory of Mind,” published in Science in 2013. Boiled down, the authors claimed reading literary fiction makes you smart. And, who knows, maybe it does, but if so, their study gets no closer to understanding why–or even what anyone means by the term “literary fiction” as opposed to, say, “science fiction.”

Our study defines those terms, creates two texts that differ accordingly, and then studies how readers respond to them. The results surprised us. Readers read science fiction badly. If you’d like all the details why, head over to Scientific Study of Literature. Meanwhile, here’s a preview, beginning with the study set-up:

Rather than selecting different texts based on expert but unquantifiable impressions of literariness or nonliterariness, our study uses a single, short text that we manipulate to produce isolated and controlled differences. The text is less than a thousand words and depicts a main character entering a public eating area and interacting with acquaintances including a server after his negative opinion of the community has been made public. We designate the first version as “Narrative Realism,” the common designation for literary fiction that takes place in a contemporary setting but does not fit another subgenre, such as romance or mystery, that also takes place in contemporary settings. In the narrative realism version, the main character enters a diner after his letter to the editor has been published in the town newspaper. Rather than attempting to study multiple subgenres, we select one, designating the second version “Science Fiction,” the most common term for fiction that includes such “accessible, well known features” as “interplanetary travel and aliens,” “hypothetical advances in technology and science,” and being “set in the future” (Dixon & Bortolussi, 2005, p. 15). In the Science Fiction version, the main character enters a galley in a distant space station populated by humans, aliens, and androids. The Narrative Realism and Science Fiction versions are identical except for setting-creating words, such as “door” and “airlock.” Both versions, therefore, should promote identical levels of theory of mind, requiring a reader to draw inferences about the main character’s and other characters’ unstated thoughts and feelings.

Because Kidd and Castano (2013) identified theory of mind as the distinguishing quality of literary fiction, we also created two versions of Narrative Realism and Science Fiction. The first version of each included statements that directly state a character’s thoughts and feelings, for example, “Jim knows everyone in the diner will be angry at him.” The second version of each includes no theory of mind explaining statements. The versions of the texts that include theory of mind explaining statements should have lower theory of mind demands than the versions that do not include them, because the explanations state the inferences the text would otherwise only imply. If theory of mind is the defining quality of literary fiction, then the texts with theory of mind explanations would be comparatively nonliterary.

In addition to theory of mind, we address an additional form of inference, which we call theory of world. Where theory of mind requires the inference and representation of a character’s implicit thoughts and emotions, theory of world requires the inference and representation of a world’s implicit laws and systems, potentially including such things as laws of physics, systems of social organization, and public history. Both texts, for example, include a sentence that begins: “He was awake in his bunk just a few hours ago, staring at …”; the narrative realism version then continues: “… the shadows of his ceiling slowly ebbing to pink, when the delivery kid’s bicycle rattled onto the gravel of his driveway,” while the science fiction version continues: “… the gray of his sky-replicating ceiling slowly ebbing to pink, when the satellite dish mounted above his quarters started grinding into position to receive the day’s messages relayed from Earth.” Although theory of world would be present in both Narrative Realism and Science Fiction, because Narrative Realism’s world is a representation of the reader’s world, theory of world demands are minimal. Because science fiction often depicts worlds that differ significantly from a reader’s world, theory of world demands would be higher. The narrative-realism text then should promote theory of mind but not theory of world, and the science-fiction text should promote theory of mind to the same degree as the narrative-realism text and theory of world to a greater degree.

Such an understanding, however, treats both theory of mind and theory of world as intrinsic qualities, while ignoring the role of extrinsic influences. The term “narrative realism” is sometimes conflated with the term “literary fiction” because narrative realism is a genre distinct from “genre fiction” and exists only in the sometimes mislabeled category of “literary fiction.” But if literary fiction is defined by theory of mind, a story’s setting, whether realistic or fantastical, indicates nothing about its literariness. However, while neither narrative realism nor science fiction then are more likely to be literary in terms of intrinsic qualities, we hypothesize that the narrative-realism text is more likely to be extrinsically identified as literary and that the science-fiction text is more likely to be extrinsically identified as nonliterary. Because theory of world is more prevalent in science fiction than in narrative realism, the promotion of theory of world processing is also more likely to be extrinsically identified as nonliterary.

And here are some of our results:

Addressing the effects of genre first, in comparison to Narrative Realism readers, Science Fiction readers reported lower transportation, experience taking, and empathy. Science Fiction readers also reported exerting greater effort to understand the world of the story, but less effort to understand the minds of the characters. Science Fiction readers scored lower in comprehension, generally and in the subcategories of theory of mind, world, and plot. The last finding is striking because Science Fiction readers reported exerting the same level of effort for understanding plot as Narrative Realism readers, but their actual comprehension of plot was weaker. Science Fiction readers reported exerting a lower level of effort for understanding theory of mind than Narrative Realism readers, and scored comparatively lower in theory of mind comprehension. Science Fiction readers even scored lower in theory of world comprehension, the one area they reported higher inference effort than for Narrative Realism readers.

Comparatively higher theory of world effort and lower theory of world comprehension, however, should be expected because a narratively realistic setting is understood to be a representation of the reader’s own world, allowing high comprehension with little effort. The science-fiction setting demanded far more inference and so greater effort to achieve comprehension. As discussed, we hypothesized this difference in theory of world to be a defining difference between science fiction and narrative realism.

The Science Fiction’s lower plot and theory of mind scores, however, are not a result of intrinsic qualities, unless the theory of world features influenced theory of mind processes. Because the science-fiction and narrative-realism texts differ according to theory of world but are essentially identical for plot and theory of mind, effort reports and comprehension of plot and theory of mind should be statistically the same. Therefore we conclude that the difference is a product of the readers’ prior social constructs regarding texts like Science Fiction and Narrative Realism. Since science fiction is “characterized as being focused on settings and content, with comparatively less emphasis on interpersonal relationships” (Fong, Mullin, & Mar, 2013, p. 371), that expectation may produce an assumption of nonliterariness for readers who also experience theory of mind-promotion as a primary quality of literariness. Science fiction story details would therefore produce a lower perception of literary quality. Based on their low theory of mind effort scores, the Science Fiction readers expected a story that involved less theory of mind. This expectation, or a subsequent exertion of less theory of mind effort, would also account for the low theory of mind comprehension. Though readers were neutral regarding plot effort, lower plot comprehension suggests a generally lower exertion in reading effort. The Science Fiction readers appear to have expected an overall simpler story to comprehend, an expectation that overrode the actual qualities of the story itself. The science fiction setting triggered poorer overall reading.

And if you’d like to see the actual texts we used in the experiment, they’re now here.

- 66 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

23/10/17 The Words of Mariko Tamaki

Mariko Tamaki’s Hulk No. 1 premiered last January, and though the series has switched artists three times, Tamaki remains the writer for No. 11 out this month. While a newcomer to Marvel and superhero comics generally, Tamaki is a well-established and well-regarded graphic novelist, known especially for her collaborations Skim (2008) and This One Summer (2014) with her cousin, artist Jillian Tamaki. Mariko Tamaki has been praised for writing compellingly complex adolescent girls, a skill she brings to the adult Jennifer Walters, the former She-Hulk who drops the feminine prefix in exchange for a superheroic dose of repressed trauma.

While Tamaki’s character development remains impressive, Hulk No. 1 is perhaps most recognizably a Tamaki comic in its skillfully playful use of words—an unexpected link to the original The Incredible Hulk Nos. 1-6. When Stan Lee was editor-in-chief of Marvel in the 60s, the job “writer” wasn’t about outlining plots or even telling stories. It was about writing actual words. Job applicants, including the later legendary Denny O’Neil, had to fill in four pages of empty talk balloons and caption boxes from Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four Annual No. 2. More than plot or story, Lee wanted wit.

I doubt Tamaki had to take that or any other writing test to land her current Marvel gig, but she would have passed spectacularly. Hulk No. 1 highlights Tamaki’s signature style from its opening panels:

JENNIFER WALTERS’ CONDO, New York.

YES, IT COULD USE A CLEANUP. Back Off.

If the second line appeared in a talk balloon or a caption box attributed to a specific character, it would just be character-defining speech or thought. Instead, by repeating the font and borderless placement of the first line’s curtly omniscient narration, the same words surprise. Who exactly is talking to us? Walters presumably—though not in actual speech, and maybe not in actual thoughts either? In prose-only fiction, we might call this “free indirect discourse,” where a third-person narrator takes on a character’s consciousness and speech style. But prose-only fiction doesn’t have the added complexity of multiple font styles linked to assumptions about voice and narrative structure.

Starting with the third panel, Tamaki’s captions feature Walters’ first-person narration—in appropriately color-coded green caption boxes. She’s giving herself a pep talk:

Okay, Jen.

Get it together.

First day back. No big deal.

Though addressing oneself in second person is a common trope, superhero comics are premised on alter egos. Jen is literally two people. A fact Tamaki makes the most of as Walters cuts herself off as if interrupting a separate speaker.

It’s going to be fi—

How about shut up already? Stupid inside voice.

Are “Jen” and “Stupid inside voice” the same? Maybe. Or at least to the degree that the Jennifer Walters in human form and in giant, gamma-radiated Hulk form are the same. The two voices even vie for the same green caption boxes as Walters’ two forms vie for her identity.

Tamaki continues both motifs, with a later omniscient time marker (“TOO LATE TO STILL BE IN THE OFFICE”) and Walters’ internal conversation (“See?” “Everything is okay. Everything’s going to be fine.” “Thanks, voice.” “Thanks for the update. What would I do without you, voice?”). Wit aside, Tamaki’s use of words is not only character-developing, it’s form-challenging, revealing comics norms by quietly undermining them—an approach to “writing” that Tamaki honed in her earlier works.

Skim opens with text from the narrator’s diary, including a hand-drawn emoticon and a strikethrough:

My cat: Sumo [heart]

Favorite color: black red

The opening establishes the diary as the narrating premise, but the actual narration is more ambiguous. Though Skim’s words are from a diary entry, the white background of the comics page is not a representation of the diary itself—not till over eighty pages later when Jillian Tamaki draws a panel with Skim’s same handwriting but now across a notebook page with lines askew to the perpendicular angles of the panel frame. The detail highlights the ambiguity of all her narration. When, for example, she writes “P.S.” to begin the text of a caption box, is the post-script addressed to her diary or to her comics readers?

When asked by a character how she broke her arm, Skim answers in a talk balloon: “I fell off my bike.*” The asterisk links to the footnote-like caption box at the bottom of the panel: “(*Tripped on altar getting out of bed and fell on Mom’s candelabra.)” How could the contradictory annotation appear in her diary? Similarly, when Skim passes a road sign announcing a town named “Scarborough,” her narrating self respells it “Scarberia” in gothic font. Again, is the physical writing Skim’s? If so, from what moment in time—an implied future when she later records the incident in her diary? If the word rendered in its very specific font is instead only her thoughts, in what sense can it be rendered at all? Can someone think in a gothic font?

Tamaki’s words exist in an in-between state, neither entirely physical nor entirely a free-floating consciousness. The most striking combination comes late in the novel, when Jillian Tamaki draws Skim writing enormous letters across the white snow of the page:

Dear Diary

I HATE YOU EVERYTHING

It’s snowing.

The first and third lines are rendered in Skim’s narrating font, while the middle is a drawn image of her tracks in the snow. If we understand the narrating font as a literal diary entry, as the salutation overwhelmingly suggests, then Skim has only written the unremarkable statement: “Dear Diary, It’s snowing.” If the snow tracks are taken alone, then the “you” isn’t directed at her diary—and so not at a version of herself. While the other two meanings remain, the third emerges only in combination.

Tamaki is equally playfully with her scripted sound effects. While employing standard onomatopoeia with “Pop!” “Crack!” “Clic Clic,” and “THUNK,” she edges into more ambiguous language with “sniff sniff” and “giggle giggle” —words that could still possibly evoke the sounds they linguistically define. But a pencil sharpener’s “GRIND GRIND” is less plausible, and a straw’s “stir” and “stab” impossible. Toes also “clench,” and the word “apply” hovers beside a bar of deodorant as a character rubs it in her armpit. According to comics conventions, all of these free-floating words should conjure sounds through pronunciation combined with the expressive size and shape of the letters. Though Tamaki’s words are instead descriptions, she and Jillian Tamaki still use letter rendering to communicate meaning with the word “swirl” written in atypical script beside the circles of motion lines inside a beaker.

This One Summer features many of the same complexities. The opening pages include the “crunch crunch” of feet on pebbles and the “bonk” of a book striking the back of a head, but soon Tamaki’s soundless sound verbs appear too: stab, nod, shrug, churn, off, wiggle, bounce, flop, push, dump, and inhale. In one instance, Jillian Tamaki even renders a sound effect misspelled with “gulg” written above a pouring drink. The reversed letters prevent the would-be pronunciation of “glug” from directly evoking the implied sound, instead using its visual placement only.

The word, like almost all of the Tamakis’ one-word effects, can easily go unnoticed, emphasizing the fact that practically any word, any clump of letters placed in the right sound-evoking area of an image, will register as the appropriate sound. The words then are primarily images. The Tamakis demonstrate that fact by placing musical notes across multiple panels to indicate a song playing from a stereo—an effect nearly identical to the use of the sounds letters “ticka ticka” over several later panels to indicate rain on the roof.

But sound effects are also more than their sounds. In the novel’s most striking use of language, Mariko Tamaki scripts the word “Slut. Slut. Slut. Slut.” behind the image of the walking protagonist’s flip-flops. The insult is in her thoughts after hearing older boys use it to flirt ambiguously with other, older girls. The sound effect then is not omniscient, the unassuming norm of most sound effects and so identical to all listeners. Instead it is a sound filtered through one character’s unmarked consciousness. Her flip-flops are calling only her a slut.

It may be unfair to attribute all of these word effects to Mariko Tamaki and not her cousin since they are all rendered in her cousin’s art—adding another ambiguity to the already complex play of language and art. Although I counted only one norm-bending sound effect word in the solo stories of Jillian Tamaki’s recent collection Boundless, artist Nico Leon only draws such standards as “CLICK,” “DING,” and “SHUFFLE SHUFFLE” in Hulk No. 1. Perhaps Marvel editor Mark Paniccia found Tamaki’s words too peculiar for mainstream fare, or Tamaki did, or the effects really are a hybrid product of her collaborations with her cousin.

But wherever they occur, the range of these quietly revolutionary image-texts reveal the Hulk-like duality at the heart of the comics form.

[Original versions of this and my other recent comics reviews appear in the comics section of PopMatters.]

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

16/10/17 The Escapist and Aeroman in Literary Superhero Team-Up No. 1!

When Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay won the Pulitzer in 2000, it bestowed upon the lowly figure of the comic book superhero the superpower of literary legitimacy. Jonathan Lethem’s 2003 The Fortress of Solitude made the mutation permanent. So kudos to the highbrow dynamic duo for teleporting long-underwear characters over to the land of the intellectually bookish. But the transformation was as much a curse as a blessing. The superheroes Escapist and Aeroman say a lot more about death than rebirth.

Asked what inspired his novel, Chabon answered:

“I started writing this book because of a box of comic books that I had been carrying around with me for fifteen years. It was the sole remnant of my once-vast childhood collection. For fifteen years I just lugged it around my life, never opening it. It was all taped up and I left it that way. Then one day, not long after I finished Wonder Boys, I came upon it during a move, and slit open all the layers of packing tape and dust. The smell that emerged was rich and evocative of the vanished world of my four-color childhood imaginings. And I thought, there’s a book in this box somewhere.”

Chabon published Wonder Boys in 1995 and Kavalier and Clay in 2000, so he was drafting during one of the darkest moments of comics history. The superhero was bankrupt. Marvel filed for Chapter 11 protection in 1996, and though it battled its way out the following year, the surviving market was a shred of its pulp glory.

I have my own move-weary box of a whittled-down comics collection in my attic. I was born in 1966, Lethem in 1964, Chabon in 1963, so our four-color childhoods are a Bronze Age overlay. The seventies may lack the primordial Ka-Pow! of the forties or sixties, but it was a damn good if idiosyncratic decade for superheroes. Too bad Chabon isn’t interested in it.

Kavalier and Clay is instead a tale of the Golden Age superhero, and so an inevitable tragedy. The Escapist begins as “an escape artist in a costume,” freeing people from oppression by the light of his Golden Key. But in the end, he can’t even free himself, much less his creators.

“’Today,’ Anapol said, ‘I killed the Escapist.’”

Anapol isn’t a time-traveling supervillain from a parallel dimension. He’s a publisher. And he’s done trading punches with super-publisher DC and its legion of lawyer-minions in a never-ending battle of copyright infringement. The guy’s just not worth the financial effort anymore.

“Superheroes,” says Anapol, “are dead, boys.”

It’s the mid-50s, and, Chabon informs us, the “age of the superhero had long passed . . . all had fallen under the whirling thresher blades of changing tastes,” with DC’s lone survivors “forced to suffer the indignity of seeing their wartime sales cut in half or more.” But even dead, the Escapist, having “long slipped into cultural inconsequence,” would “always be there” for his creators as a “taunting” reminder of “the wealth and unimaginable contentment” they never reaped.

Meanwhile, the novel’s lone, fantastical entity, the Golem of Prague, meets a similar end. An enormous box filled seven inches deep with silt from the Moldau River arrives by mail: “The speculations of those who feared that the Golem, removed from shores of the river that mothered it, might degrade had been proved correct.” A coffin of dirt. That’s all that’s left after Chabon’s done firing his literary cosmic rays at the Golden Age of comics.

Lethem’s superheroes fair no better. His “flying man” (no caps, poor guy doesn’t even earn a superhero name) first appears in 1973, as the Silver Age is plummeting into the Bronze. “He looked like a bum,” with a bedsheet cape stained yellow with pee, “needing a drink more than anything.” He can’t even land right (“Fucked up my motherfucking leg”) let alone stay airborne. Next thing he’s “curled in a ball” in front of a liquor store, “baked in vomit and urine and sweet” in a “mummified pose.”

So ends the Silver Age. But once hospitalized, “no-longer-flying man” becomes “a symbol of possible atonement” when he passes on his magic ring (it’s a Green Lantern riff) to Lethem’s stand-in, the adolescent Dylan, who rechristens himself Aeroman. Sounds better, but the key word is “possible,” because Dylan wastes the rest of the novel failing to launch. He slowly realizes he’s “no superhero at all” but a “coward” with “an irrelevant secret power,” and when his best friend, Mingus, uses the ring, Aeroman is still only a “would-be hero,” screwing up a police sting while getting himself arrested. Dylan’s costume (or “homo suit”) is soon “lost or destroyed,” and Dylan and Mingus’ shared identity (“world’s most pathetic superhero”) is now a symbol of their dissolving friendship.

The ring is last seen on a coke-smeared mirror, before vanishing into Dylan’s post-college apartment. When next worn, instead of flight (“that part of it was dead”), it gives Dylan invisibility. But he proves as incompetent as ever, termed a “warped vigilante” when his next outing ends in accidental death (“I only wanted to help”). Aeroman was birthed from adolescent “desolation,” and Dylan finally flings the “curse once and for all into the brush at the side of the highway.” It makes a final appearance on the finger of Dylan’s childhood enemy after he’s leaped to his death—a presumed suicide.

Entrance into the League of Literary Superheroes comes with a stiff price. These are great novels, but rather than reanimating superheroes, Chabon and Lethem incinerate them. And is it coincidence that the character type entered highbrow circles only after comic books—the pulpiest of the pulps—had died? Comic shops in the U.S. peak at 12,000 in the early 90s. When Chabon finished Kavalier and Clay, only 3,000 remained. And they no longer welcomed kids. When Lethem finished Fortress, the average reader was 25, up from 12 when he, Chabon, and I were amassing our childhood collections.

We’re not the only ones.

Tags: Jonathan Lethem, Michael Chabon, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, The Fortress of Solitude

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

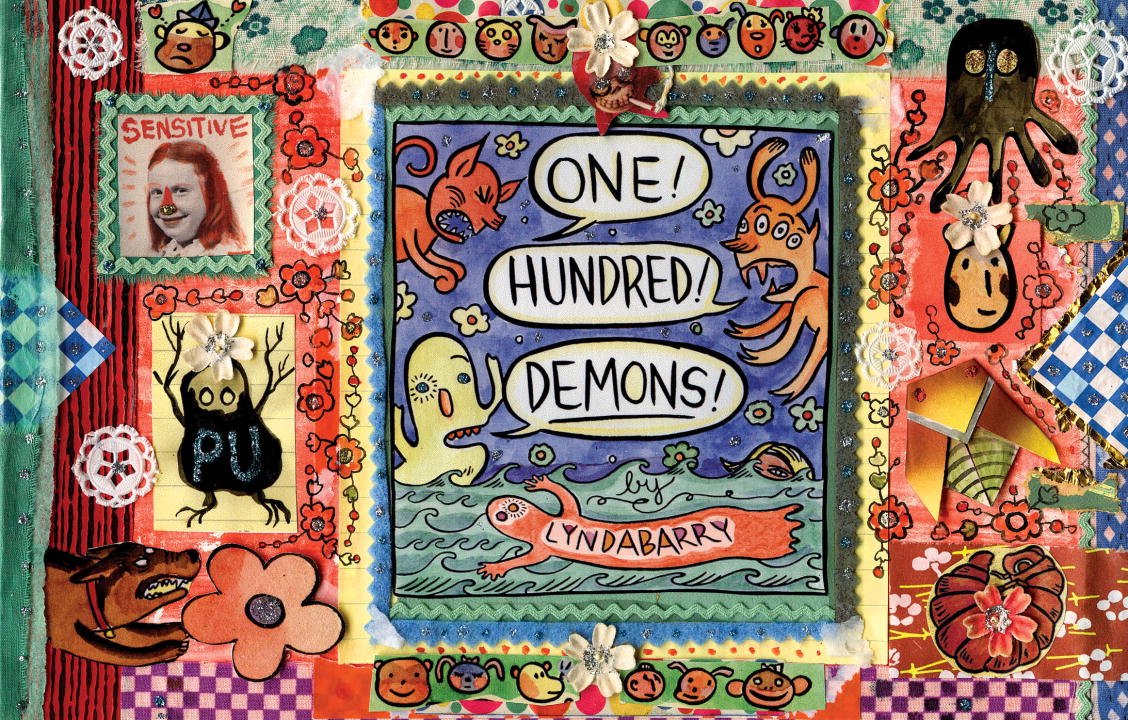

Lynda Barry originally published her first memoir, One! Hundred! Demons! (Drawn & Quarterly 2017), as eighteen, serialized web comics on Salon.com from 2000-2001 and then as a collected book in 2002. (They’re still

Lynda Barry originally published her first memoir, One! Hundred! Demons! (Drawn & Quarterly 2017), as eighteen, serialized web comics on Salon.com from 2000-2001 and then as a collected book in 2002. (They’re still