Monthly Archives: March 2019

25/03/19 What Does “Plotte” Mean?

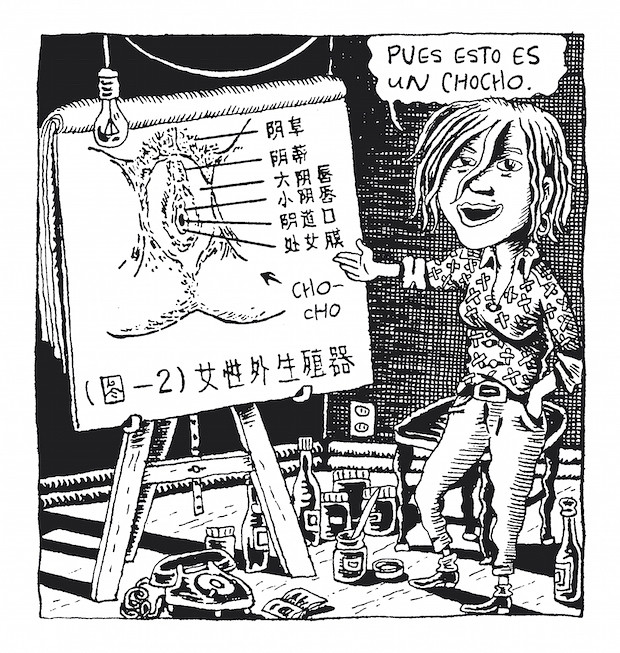

I don’t speak French and have never even visited Quebec, so my googled translation of plotte as “vagina” and “slut” likely misses some cultural connotations. Julie Doucet’s longer and better explanation includes a map and diagram and appears in one of the first issues of her ground-breaking 90s comic Dirty Plotte—or rather her bandes dessinées, literally “drawn strips,” the French term and tradition Doucet was responding to.

I have never read Doucet in her original format, but my bookshelf includes My Most Secret Desire (2006) and My New York Diary (2013), two reprint collections of roughly 100 pages each. Happily, her original publisher Drawn & Quarterly released a complete collection, Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet, a massive anthology spanning over 600 pages. It amasses not only all twelve, twentysomething-page issues of the original 1990-1998 series, including full-color front and back covers, but also roughly two hundred pages of additional work produced during the same period. The combination is a startling body of work that further deepens Doucet’s place in the comics cannon.

Dirty Plotte began as a late 80s series of two-page mini-comics, which, if we believe the cover price, Doucet sold for only a quarter. Most of them appear within the pages of the expanded series, one of the first publications launched by Drawn & Quarterly—with, according to the second issue, the grant support of the Canadian government’s ministry of cultural affairs. That fact is a stark contrast to the roughly simultaneous controversy in the U.S. over the National Endowment of the Art’s funding of Piss Christ (1987), with conservative Republicans attempting to eliminate the NEA entirely in 1990. I can only imagine how they would have responded to Doucet’s comic about eating the decapitated and butchered body of Christ on her dining room table or the one about a serial killer murdering a child (a young Doucet?) in a park and feeding the corpse to his trusty dog.

I know Doucet primarily as a memoirist whose diary-like subjects are the recent events of her waking life as well as the surreal happenings of her sleeping subconscious. Both paint a vivid and now expanded self-portrait. The dream Doucet eats a butter-oozing croissant protruding from a man’s briefs; watches her comics role model Chester Brown swim with killer sharks; is stabbed in the eye with a drug-filled syringe; receives the gift of a cut-off penis from a friend (it may or may not grow back); masturbates with homemade cookies in a spaceship; wanders lost in the underground tunnels of New York; has sex with her mirror self; and witnesses a prostitute strip off her clothes and then her skin to reveal a dog who strips down further to a snake before giving a blowjob.

Though many of her other stories are equally surreal, Doucet is careful to distinguish dream content, citing a “true dream” or a “story based on a long time dream” or dating both the dream and the comic separately (“Dreamt July 1995 – drawn January 1996”). The distance of even a few months makes the work memoir not diary, but the effect is still diary-like as Doucet documents the disturbed and disturbing events of her subconscious life. She also nods at early 20th century comics pioneer Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland strips, each of which ends with the child protagonist waking in bed—a pose the cartoon Doucet often repeats.

Her conscious world, however, isn’t clearly divided from her dream life. Many of the dreams begin ambiguously, implying real-world events that then devolve uncomfortably. Her non-dreamt content is infused with many dream-like qualities too. After declaring, “I’m in my bed! It was only a dream …,” the cartoon Doucet is surrounded by the objects of her apartment literally muttering murderous threats. Her own cats can not only talk, but lead their own anthropomorphic adventures continued across multiple issues. Other stories begin realistically and then turn not to dreams but fantastical comedy—as when she visits an old friend to find that he has a dog so big that your voice will echo if you shout down its penis. Still others are dream-like wish-fulfilments, as when she murders her annoying roommate or imagines multiple installments of “If I Was a Man” (it turns out a penis can make a lovely flower vase).

Doucet’s creative id, whether awake or asleep, knows few boundaries—or rather seeks out boundaries to challenge. I’m not sure whether I’m more uncomfortable looking at Doucet’s self-portraits covered in self-mutilating razor wounds or when she more graphically mutilates a male volunteer’s body. She is also “dirty” in both senses, depicting herself as a nose-picking slob living in surreal squalor and as an insatiable masturbator craving elephant trunk. Like her contemporary, Fiona Smyth, there is a fair amount of “joyous sucking” in these pages—but Doucet’s sexual universe is overall much darker. While the dreams and waking fantasies disturb, it’s her less surreal, less sensationalistic memoirs that most upset.

The first installment of what she would later collect as “My New York Diary” begins in Dirty Plotte No. 7. The ten pages, the longest sequence yet, recounts her seventeen-year-old self foolishly falling in with a group of men who variously coerce her into kissing and eventually having sex. It’s not presented as a rape scene, but the cartoon Julie’s “Oh, well” thought bubble is hardly joyous even if she does leave the apartment pleased with her sudden adulthood. As one of Doucet readers writes generally of the series: “Julie, it’s really not very funny, is it?”

Yet Doucet’s visual style is comical. These are cartoons in the exaggerated sense, impossible anatomy that evokes the human proportions it warps. The heads of Doucet figures are roughly 1/5th their height, so roughly double the size of human heads. They pose and move in clunky, almost Peanuts-esque shapes. The artistic choice often reduces the level of discomfort in each scene. A more naturalistically drawn seventeen-year-old Doucet pinned on a mattress under a gray-bearded man sounds like an image more horribly at home in a Phoebe Gloeckner collection. Doucet instead allows her reader and perhaps herself off the hook by refiguring her dreams and memories into unrealistic realities.

The collection is divided into two, oddly distinct books, each with its own title page and numbering. The first is the complete Dirty Plotte series. But rather than interspersing Doucet’s non-Plotte material between issues, the editors rewind to the late 80s and begin the timeline over with literally “Everything Else.” Everything includes almost a dozen short essays about and interviews with Doucet by an array of comics aficionados: Dan Nadel, Diane Noomin, Chris Oliveros, Adrian Tomine, Jami Attenberg, J.C. Menu, Andrew Dagilis, John Porcellino, Geneviève Castrée, Laura Park, Martine Delvaux, and Christian Gasser. All but the last were published during Doucet’s comics career, which Gasser’s interview looks back over from the vantage of 2017.

To be clear, the “Complete” in the collection’s title refers only to Dirty Plotte and similar work she produced at roughly the same time. So it does not include her 365 Days: A Diary (2008) or Carpet Sweeper Tales (2016), works that break from her 90s style and content—though not necessarily the comics form, despite claims that Doucet left comics entirely after 1999. It does, however, include the forty-one-page episodes of “The Madam Paul Affair,” her first major work after ending Dirty Plotte.

Wandering back through the 90s again, it’s often unclear why certain material was included in Dirty Plotte and other wasn’t. There are more dreams (pregnancy), new cat adventures (now in a Western setting), and “If I Was a Man” installments, and works like “Heavy Flow” and “Janet and the Tampons” feel like long-lost sisters. But some of the gutter shapes are more playful—several waves and squiggles stand out—and an occasional page like “The Kiss,” an apparent homage to Klimt, do seem wonderfully out-of-place. Perhaps if Doucet had felt freer to experiment in these ways she might not have left comics at all?

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet, Drawn & Quarterly, Julie Doucet

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

18/03/19 Defining Comics Definitions

Comics studies—one of the few fields of study that can’t agree on what it’s studying–suffers from a decades-long disagreement over the definition of “comics.” I’m hoping to discuss that disagreement in my next book. Happily, explaining the disagreement isn’t a book-length project. I think I can do it in one paragraph here:

Setting aside supplementary terms such as “graphic novel” and “graphic narrative” coined to replace without helping to define “comics,” the ur-term has at least four overlapping yet competing meanings:

comics the form (any sequence of images);

comics the conventions (a subset of image sequences that use panels, gutters, talk balloons, etc.);

comics the cartoon (a set of image style conventions that simplify and exaggerate forms but not necessarily in sequences); and

comics the publishing history (which prevents the anachronistic application of the term to art created before the 1890s and also to any image or image sequence not understood to be a comic by the artist or curator).

Various comics scholars champion the various definitions, though usually without acknowledging that more than one is in play or that apparent disagreements are the result of talking past each other, since a “comic” is not a “comic” is not a “comic.” Thus Gary Larson’s one-panel The Far Side poses an unsolvable riddle for comics the form, while posing no challenge at all to comics the cartoon or comics the publishing history.

I could map the origins of the confusion (Punch magazine, 1843), but I’d rather map the concepts first. It’s a Venn diagram: Or actually two:

Or actually two: Layered on top of each other:

Layered on top of each other: That creates 13 distinct zones, each with its own meaning. Since that’s visually complex, I’m adding gradations:

That creates 13 distinct zones, each with its own meaning. Since that’s visually complex, I’m adding gradations: The white sections have no areas of overlap, the light gray sections have two, the dark gray three, and the black center four:

The white sections have no areas of overlap, the light gray sections have two, the dark gray three, and the black center four: Now drop in the four corresponding definitions:

Now drop in the four corresponding definitions:

Every possible “comic” falls somewhere on the diagram. The least controversial land in the middle, which is the source of the confusion.

Every possible “comic” falls somewhere on the diagram. The least controversial land in the middle, which is the source of the confusion. Probably all would agree that a Krazy Kat comic strip is a “comic,” but each of us might have different reasons for making that conclusion, some of which we might share and some we might not. I, for instance, favor “comics the form” and so would classify Krazy Kat a comic because it is a sequence of juxtaposed images, regardless of its other characteristics. But it is also a comic in the other three senses. If someone else favors, for instance, “comics the publishing history,” then our apparent agreement about Krazy Kat masks a deeper disagreement. Or rather an unacknowledged misunderstanding, since my “comic” and your “comic” are secretly homonyms. We’re literally using different words.

Probably all would agree that a Krazy Kat comic strip is a “comic,” but each of us might have different reasons for making that conclusion, some of which we might share and some we might not. I, for instance, favor “comics the form” and so would classify Krazy Kat a comic because it is a sequence of juxtaposed images, regardless of its other characteristics. But it is also a comic in the other three senses. If someone else favors, for instance, “comics the publishing history,” then our apparent agreement about Krazy Kat masks a deeper disagreement. Or rather an unacknowledged misunderstanding, since my “comic” and your “comic” are secretly homonyms. We’re literally using different words.

Krazy Kat also fulfills “comics the conventions” and “comics the cartoon,” which massively overlap, since cartooning is one of many conventions, making it sufficient but not necessary to fulfill “comics the conventions.” That might mean that “comics the cartoon” is contained entirely within the area of “comics the conventions,” which the above diagram doesn’t demonstrate because a) I don’t know how to draw that and b) it might not be true.

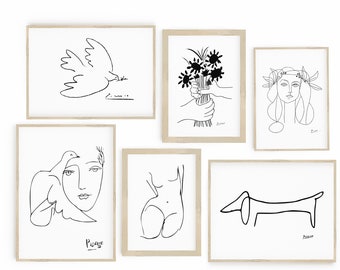

Picasso’s late period includes a range of line art that satisfies the definition of cartoons but that very few would classify as cartoons.

So is a cartoon that is not called a cartoon a cartoon in the “comics the conventions” sense? Or is the problem that Picasso doesn’t fall under “comics the publishing history”? I’m not sure.

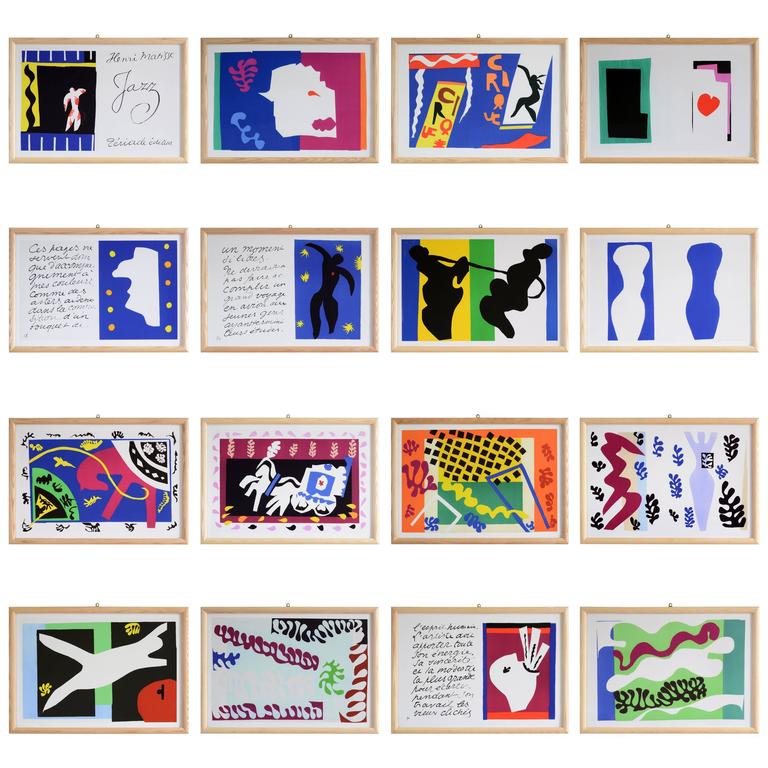

Other examples will fall into other areas to reveal other previous ambiguities. Matisse’s book Jazz combines form and cartoon, but not conventions and publishing history.

Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe is a comic in terms of form and conventions (panels, grid, color separation), but not cartoon and publishing history.

The Far Side, mentioned above, lands in the bottom “3,” combining conventions, publishing history, and cartoon, but not form since each is a single panel.

As I continue to refine this definitional approach, I’ll need to number (and perhaps name?) each of the 13 areas and provide examples for each. But I hope this provides the groundwork for defining the definitions of comics.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

11/03/19 Is God Bipolar?

Keiler Roberts lives in a deadpan universe ruled by a bipolar God. Her graphic memoir Chlorine Gardens is a fractured chronicle of self-deprecatingly hilarious yet harrowingly moving vignettes from the edge of her private yet oh-so-familiar abyss. Really, she has it pretty good: a comfortable life in a suburban home filled with loving family members and ample art supplies. Also, her grandfather just died and she’s been diagnosed with MS. But rather than best-of-times worst-of-times rants, Roberts’ humor is perpetually even-keel—a line as endearingly flat as the never-quite-smiling, never-quite-frowning mouths she draws on her and family’s faces.

Given her anti-sentimental tone, Roberts’ drawing style is appropriately sparse: thin, black contour lines give her world realistic proportions, but without crosshatched shadows and depth. All shapes are empty shapes. The universe is not only colorless; it rejects gradations too. But her always simplified renderings are never cartoonishly exaggerated either. Though any photographic source material feels distantly filtered, its underlying realistic integrity remains. This is our world—just less so.

Roberts matches the visual flatness of her panel content with similarly flat layouts of mostly 3×2 and 2×2 grids, punctuated by occasional full-page images. Each panel is framed by the same thin black lines that shape the images, gently challenging the conventional illusion that the white of the page background visible in the gutters is any different from the white of the story-world spaces inside the frames. In both cases, there just isn’t a lot holding everything together.

And yet her world, her family, Roberts herself—they do hold together, in part from the warmly ironic wit she threads through each scene. As a parent who kept a journal of the most endearing and inappropriate things my children said growing up, I know the pitfalls Roberts avoids as she chronicles her home life with an early school-aged daughter. In other hands, the six-year-old Xia—even as she’s echoing her mother’s “shit” and “goddamned” expletives—would be too cute, just a variation of parental bragging.

Instead, moments with Xia, like Roberts’ self-portrayal generally, is grounded by the graphic memoir’s overarching tone of struggle. Yes, life may be pretty goddamned good—but what’s that have to do with being happy? The memoir opens with Roberts telling Xia her birth story, yet by the end of the sequence she is clearly stating things not meant for her daughter’s ears. “I think,” Roberts’ drawn self later tells her viewers, “I started making comics so I could stop fearing the loss of my irreplaceable things.”

“Things” are central. Roberts lists some of her favorites and least favorites—including Coltrane’s jazz cover of “My Favorite Things.” Her favorite glass appears in a wallpaper pattern beside a vodka bottle on the inside of the cover. It appears again on the inside of the back cover, except beside a carton of milk. Somewhere between, she mentions that she’s stopped drinking and that “I never use my favorite glass anymore because I’m afraid I’ll break it.” She later lists first symptoms of MS, jokingly calling each her favorite thing too. “Nothing,” she explains, “exists without meaning and sentimental value,” and so “every object blooms with associated memories and feelings.” And as though to prove it, she ends the memoir with her mother lamenting that she has only “four of those wonderful frozen cheeseburgers from Costco left. They stopped carrying them.” The comment would seem aggressively mundane, and though Roberts’ character responds with only a simple “I’m sorry,” ten pages earlier she drew her dying father eating one of those cheeseburgers, calling it the moment she felt the loss of him.

Much of Roberts’ skill is in her understated use of the comics form—which is based on gaps and absences and so kinds of loss too. Roberts often leaves out key, dramatic moments. One panel caption explains that her beloved dog “bit some people,” and in the next she’s driving him “to the vet to put him to sleep.” She avoids not only the biting incident but the immediate drama of its aftermath when the victim presumably contacted authorities who agreed that the dog had to be put down. Instead, Roberts draws her “perfect” pet in the front seat, under the caption: “He sat up calmly.” In the next panel, she is alone in an examination room, with her hand on the blanket-covered dog. The panel reads: “Scott was in New York.” The understated fact echoes with a blur of emotion—all unverifiable by her expressionless face.

That kind of image and word juxtaposition is another of Roberts’ comics skills, the way she plays the two modes against each other for subtle contradictions. When she states that “Scott sometimes watches football,” she draws her husband swinging their daughter around the living room as they shout “Touchdown!”—it’s unclear whether the TV is even on. When she’s explaining the nostalgia-like loss she feels in all objects, “It’s a wanting that can’t be satisfied,” she draws an angled eBay image of a “Barbie mixed lot from the 80’s” on the phone held in her hand. The mundaneness undercuts the spiritual depth of her words, as though her internal artist is gently mocking her internal writer.

The effects are subtle, but subtle is as good as it gets in Roberts’ universe. She posits a bipolar God to explain how “inconsistently great and terrible his creations are,” and then counters that volatility with her own deadpan consistency—though with just enough hint of a Mona Lisa smile to betray the love and joy struggling under the starkly drawn surface of all things.

![]()

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

[Also, despite my inability to defeat wordpress’ obscure and dysfunctional auto-formatting, here’s an email conversation I had with the author:

From: Keiler Roberts

Sent: Sunday, September 30, 2018 3:52:00 PM

To: Gavaler, Chris

Subject: Chlorine Gardens review on PopMatters

From: Gavaler, Chris <GavalerC@wlu.edu>

Sent: Sunday, September 30, 2018 12:54 PM

To: Keiler Roberts

Subject: Re: Chlorine Gardens review on PopMatters

From: Keiler Roberts

To: Gavaler, Chris

Subject: Re: Chlorine Gardens review on PopMatters

From: Gavaler, Chris <GavalerC@wlu.edu>

From: Keiler Roberts

From: Keiler Roberts

From: Gavaler, Chris <GavalerC@wlu.edu>

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

04/03/19 Technique, Style, Image, Story

Which comes first?

Traditionally comics begin with a story idea that a writer develops into a screenplay-like script before handing it off to an artist to sketch into a layout in whatever style that artist prefers. The first page of my current comic-in-process includes the following text:

“He couldn’t believe he lost to a girl. Afterwards he played Rubik’s Cube in the backseat as his dad drove them to his sister’s recital.”

A script would include image content too, usually divided into a specific number of panels. But this isn’t how my creative process began. I started by experimenting with a technique. More specifically, I started with a cartoonish self-portrait from a photograph taken of me at Lexington’s MLK parade in January.

Since I refuse to enter the 21st century and abandon the now literally obsolete (it was discontinued last year) Microsoft Paint, I was looking for ways to create color shapes by first mouse-sketching lines, filling the areas they enclose, and then digitally removing the lines:

Since I refuse to enter the 21st century and abandon the now literally obsolete (it was discontinued last year) Microsoft Paint, I was looking for ways to create color shapes by first mouse-sketching lines, filling the areas they enclose, and then digitally removing the lines:

I wasn’t aiming at any particular style, so the results were pretty garish–until I figured out that once the black lines were gone, I could convert the colors to black:

I wasn’t aiming at any particular style, so the results were pretty garish–until I figured out that once the black lines were gone, I could convert the colors to black:

The red was another experiment, sort of a Matisse-esque cut-out placed digitally “under” the image. I converted the first two images to the same style:

The red was another experiment, sort of a Matisse-esque cut-out placed digitally “under” the image. I converted the first two images to the same style:

I was working on other, unrelated images too:

I was working on other, unrelated images too:  With the technique down, I could then create new images in the same, now intentional style:

With the technique down, I could then create new images in the same, now intentional style:

Though related by style, the image content was still random. But since each was roughly rectangular, I began arranging them in a 3×2 page layout:

Though related by style, the image content was still random. But since each was roughly rectangular, I began arranging them in a 3×2 page layout: The gap required a sixth, and this time I decided on a specific subject matter, a figure playing chess:

The gap required a sixth, and this time I decided on a specific subject matter, a figure playing chess:

Placing the new panel in the missing position in the bottom row produced this juxtaposition:

Placing the new panel in the missing position in the bottom row produced this juxtaposition:

And that’s when “story” happened. Staring at the two panels, these words came to me:

And that’s when “story” happened. Staring at the two panels, these words came to me:

I was sitting in a school cafeteria during one of my son’s chess tournaments (which he later won), so the influence is obvious enough, but the exact content, how the two figures in the two images became characters interacting with each other in a shared setting with specific outcomes, was a result of the connotative qualities of the images and their accidental placement next to each other. More words happened:

I was sitting in a school cafeteria during one of my son’s chess tournaments (which he later won), so the influence is obvious enough, but the exact content, how the two figures in the two images became characters interacting with each other in a shared setting with specific outcomes, was a result of the connotative qualities of the images and their accidental placement next to each other. More words happened:

I placed the two story-initiating panels at the top of the page and rearranged the others beneath them:

I placed the two story-initiating panels at the top of the page and rearranged the others beneath them:

The effect is odd in part because off the amount of implied and so undrawn story-world content, including the car connecting panels three and four, and the auditorium connecting five and six. That last row plays with time, since the words are synced to the continuing moment in the car, while the images leap forward to the performance that, according to the words, is still in the future. The chess-playing son acquires a face and perhaps the hint of a smile, suggesting that he will recover from his disappointment by (or simply while) enjoying the dance. Because there’s now an implied family unit, one of the parents is absent–a fact left open and so to be explored on future pages. Since the dancers appear female (is the one in the background the sister?), I feel a thematic connection to the “girl” of panel two in addition to the undrawn mother, further complicating the gender situation. Oh, and dad seems pretty oblivious in row two, staring off into the left margin as he drives unaware of his son’s literally inward focus–but then they’re physically connected in the last row, suggesting another positive shift in the ending. Of course all of this is connotative and so debatable. No script would include these kinds of interpretive nuances, and probably no artist could execute them based on idea-driven descriptions.

The effect is odd in part because off the amount of implied and so undrawn story-world content, including the car connecting panels three and four, and the auditorium connecting five and six. That last row plays with time, since the words are synced to the continuing moment in the car, while the images leap forward to the performance that, according to the words, is still in the future. The chess-playing son acquires a face and perhaps the hint of a smile, suggesting that he will recover from his disappointment by (or simply while) enjoying the dance. Because there’s now an implied family unit, one of the parents is absent–a fact left open and so to be explored on future pages. Since the dancers appear female (is the one in the background the sister?), I feel a thematic connection to the “girl” of panel two in addition to the undrawn mother, further complicating the gender situation. Oh, and dad seems pretty oblivious in row two, staring off into the left margin as he drives unaware of his son’s literally inward focus–but then they’re physically connected in the last row, suggesting another positive shift in the ending. Of course all of this is connotative and so debatable. No script would include these kinds of interpretive nuances, and probably no artist could execute them based on idea-driven descriptions.

The effect is also odd because, I realized afterwards, comics rarely subdivide sentences into multiple image-texts. We’re used to reading complete sentences of narration or dialogue placed within single panels. This layout instead divides two sentences between six panels, creating line-break effects similar to free verse:

He couldn’t believe

he lost

to a girl.

Afterwards

he played Rubik’s Cube in the backseat

as his father drove

them to his sister’s

recital.

The rows also create three image-text phrases:

He couldn’t believe he lost to a girl.

Afterwards he played Rubik’s Cube in the backseat as his father drove

them to his sister’s recital.

I’m intrigued by comics that disrupt page orientation norms by either placing the book spine along a shorter left edge or at the top so pages turn like a calendar. So I experimented with two phrases of three panels each:

Which for whatever reason, I didn’t love. But I did like the how the arbitrarily large font of “afterwards” suggested a story title, and so “Afterwards” became the title of the story:

I’m cheating a little here because the flower behind the title comes from a story element that developed on a later page, though here it doesn’t have any contextual meaning except that I thought it looked cool:

I also didn’t love the solid blocks of red, so I experimented with superimposing textures. I started by making a rectangular “scratched” pattern:

That matched the rectangular panels and layout, and so it felt redundant. So I developed a swirl pattern instead. While adding a sense of physical motion, it also has connotative power, linking the images in new ways and further suggesting emotional content. Here’s the (current) final draft:

That matched the rectangular panels and layout, and so it felt redundant. So I developed a swirl pattern instead. While adding a sense of physical motion, it also has connotative power, linking the images in new ways and further suggesting emotional content. Here’s the (current) final draft:

The larger story spans ten pages, all initiated by the story content suggested by page one. “Afterwards” may also become a chapter in a larger story. If so, the resulting graphic novel will have begun not with a story idea or even a set of images, but an image style evolved from an idiosyncratic image-making technique.

The larger story spans ten pages, all initiated by the story content suggested by page one. “Afterwards” may also become a chapter in a larger story. If so, the resulting graphic novel will have begun not with a story idea or even a set of images, but an image style evolved from an idiosyncratic image-making technique.

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized