Monthly Archives: January 2019

28/01/19 A Wilder West

I subtitle my advanced fiction writing course “Literary Genre,” which is a pairing of words most of my students haven’t seen before. Traditionally, so-called “literary fiction” and the array of genres that fall into the massive bin labeled “genre fiction” are understood to exist at opposite ends of some poorly defined spectrum. The confusion is complex, since”literary fiction” means both narrative realism (which IS a genre) and also “good fiction,” which has nothing to do with genres and so potentially applies to them all. It doesn’t help that a majority of genre fiction is formulaic and so really not literary in the second sense. Of course tons of narrative realism isn’t very good either.

So “literary genre fiction” is good fiction that uses tropes from traditional genres. Since a formulaic use of a trope tends to be predictable and plot- rather than character-driven, the trick is finding a way to evoke the qualities of a genre without simply repeating. Expectations must be thwarted. Something new has to grow out of that old terrain.

Take westerns, a uniquely U.S. genre that has mostly (though not entirely) fallen out of fashion. To write a literary western requires some repetition: can something be a western and not be set in the western U.S.? Horses and guns might be requisites too. But, like most genre, westerns have a slew of conventions that encode gender norms–redemptively violent men saving not-strong-enough women–that I hope any contemporary writer would avoid like a snake bite.

My fiction-writing class is prose-only, so I didn’t put Lisa Hanawalt’s graphic novel Coyote Doggirl on the syllabus. But since it’s an ideal example of literary genre, maybe I should have. It features a wild west as familiar as tumbleweeds yet newly invigorated by a comics artist’s feminist eye. Hanawalt roams the border lands between cartoon and naturalism, nostalgia and invention, ribald slapstick and social commentary, all while satisfying each of their disparate and often contradictory genre norms.

In the tradition of anthropomorphic animals—Buggs Bunny, Winnie the Pooh, Garfield—Hanawalt’s main character is essentially a human with a dog’s head. In this canine universe, everyone is dog-headed. She has fingers and toes, wears long pants and a “crop halter top” (which she designed herself!), and has ears that stick straight up above her snout of a face.

But though Doggirl is a cartoon character in a cartoon world, Hanawalt infuses that world with a surprising level of visual realism. If it’s never bothered you that an anthropomorphic mouse named Mickey has a semi-anthropomorphic pet dog named Pluto, then Doggirl’s pony “Red” will bother you even less. Unlike his owner, Red is thoroughly realistic. Hanawalt renders him with loving precision. While Doggirl is almost entirely devoid of anatomy-defining, internal lines, Hanawalt gives Red and other horses just enough to suggest fully realized bodies–ones that include skeletons and musculature that the dog people lack. The shadow that Red casts on the cover is evidence alone that she is drawing from real-world references—corroborated by her one sentence bio “Lisa Hanawalt lives and rides in Los Angeles” and the nine names in her list of “Some favorite horses Lisa has known.”

Doggirl’s setting is more realistic than her too. While Hanawalt’s style creates a minimalistic impression, pausing on an image allows the eye to travel over a surprising range of details—most of it in the rendering of desert and mountain plants. This world is further deepened by Hanawalt’s colors, which highlight the quirks of her brushes, giving watercolor texture to otherwise flat plains and barren skies. The openness of the western setting is also reflected in the formal choice of her unframed panels, usually three or four per page. The physical format of the book is small, about seven and a half by six inches, but the dimensions are offset by the expansive layout and bright color palette.

Hanawalt occasionally uses single-line frames too, but she avoids formal gutters except to differentiate a flashback sequence which she colors darker too. The stylistic choices are apt as Doggirl narrates escaping an attempted rape and the justified mutilation of her attacker. The event is the core of the novel’s nominal plot, driving the main character from episode to comic episode as her attacker’s brother and his two thugs pursue her for revenge.

It may sound like a typical western set-up, but in Hanawalt’s capable hands it also encompasses genre parody and gender critique. Doggirl’s minimalistic form is a welcome counterpoint to a genre that traditionally exploits female bodies both visually and narratively. When a plot point suggests an occasion for nudity, Hanawalt draws Doggirl either only partially or from behind—and then without a teasing array of crosshatched shadows that indirectly suggest the undrawn contours of exposed breasts.

But Doggirl isn’t sexually neutral either. An opening page tilted “Coyote’s Wish List” includes a “pleasure saddle” drawn with an impressive array of dildo attachments. It’s one of Hanawalt’s many tossed-off gags. Though she can be unabashedly crude, the overall tone of the novel is oddly subtle—as when the arrow-wounded Doggirl collapses, mumbling “There’s dirt in my ear.” The bird pecking at her blood puddle adds a macabre secondary punchline. While humor is the novel’s most immediate appeal, Hanawalt uses it often to complex effect, as when she draws Doggirl’s would-be rapist’s leg as if it’s been meticulously sliced by deli machine. I laughed, even internally applauded, but not without discomfort.

Doggirl is her own hero, saving herself not just from her attacker but eventually from her pursuers too. While Hanawalt is happy to include a bit of gun and knife action, ultimately Doggirl saves the day by talking herself out of trouble and more than one genre cliché. Thugs are not your typical thugs in this doggy universe. Hanawalt’s Indians are even more complex—neither savages nor noble innocents, but an odd collection of individuals happy to give aid, but only after causing pointless harm.

Coyote Doggirl is proof that even a genre as seemingly played-out as the western can reveal a rich landscape if the right hands are holding the reins.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Coyote Doggirl, Lisa Hanawalt

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

21/01/19 My Favorite Translated Graphic Novel of 2018

I never compile a list of the year’s best comics because I know there’s so many more comics out there that I’m not reading. Of the twenty or so new works I review each year, I favor my top three publishers: Koyama, Drawn & Quarterly, and Fantagraphics (not necessarily in that order), with happy surprises from other fantastic publishers I’m only starting to get to know (Self Made Hero, First Second, Seven Stories). Since my knowledge of new, non-English works is limited to translations, I feel especially lucky to have come across Anneli Furmark last year.

Because graphic novels combine story, pictures, and words, it’s rare for one to excel in all three. Anneli Furmark’s Red Winter is that exception. Though one of the most acclaimed graphic novelists in Sweden, Furmark is a newcomer to most English speakers. While I hope Drawn & Quarterly will translate and publish many more of her works in coming years, Red Winter is a remarkable introduction to this artist-writer.

It’s also an intimate window into a complexly compelling period of Swedish cultural and political history. Though Drawn & Quarterly’s back cover blurb provides the basics—“Passion and politics unfold against the darkness of winter in 1970s Sweden”—Furmark is far less direct, preferring to drop her readers into not just a historical moment but the minutia of her cast’s interlocking lives. Translator Hanna Stromberg kindly glosses the most obscure references (the APK is a Marxist-Lennist party not to be confused with the Maoist SKP or Sweden’s largest Communist party, the UPK). Though I suspect most U.S. readers will, like me, have never heard of “Bohman and his cronies” or their so-called Moderate Party—which, happily, is not a problem since Furmark provides just enough context clues in her dialogue to ground the situations. And rather than penning in clunky dates in caption boxes, she let’s the music do the talking—as when the teen son blasts Deep Purple’s 1972 “Highway Star” from his bedroom stereo.

Furmark divides her novel into nine chapters, ranging from eleven to thirty-six pages, each titled after a character: Siv, the main character who is having an affair with Ulrik, a sincere but inept member of the APK as it tries to gain influence in local unions; Marita, Siv’s pre-teen daughter who reads her mother’s diary when not playing in puddles outside; Peter, Marita’s older and adolescently angsty brother; and last and least Borje, Siv’s well-intentioned but clueless husband who works at the mill where Siv is trying to recruit. There are more—Marita’s best friend, Ulrik’s best friend, Peter’s car load of terrible friends, and of course the tale’s only antagonist, the self-important local APK leader Peter who ultimately ruins Ulrik and Siv’s future in a fit of political paranoia. But while they may sound like a lot in summary, the movement between and through scenes is seamless and the tracking of characters effortless as Furmark immerses her readers in the vibrant milieu.

The complexities of her interwoven plots are offset by a deceptively simple visual style. Her characters are cartoonish in the simplified sense, their faces rendered with a minimum number of pen strokes. But their world is darkly patterned and crosshatched, and Furmark layers watercolors over her line art for unexpected effects, often violating divisions between foreground and background, so the color of a character’s face or body envelopes them into surrounding walls or street scenes. Furmark also draws unusually thick, black frames around each of her panels. Combined with the rigid gutters of her always rectangular layout, the visual style reinforces the sense of isolation plaguing each character.

While many graphic novelists combine art and storytelling for excellent effect, the language of graphic novels can be comparatively lacking. But Furmark—at least as translated by Stromberg—wields her typewriter as carefully as her brushes. The novel opens with a kind of prose poem—though really Siv’s meandering stream-of-consciousness as she muses about secretly meeting Ulrik. A few chapters later after she’s snuck out of Ulrik’s commune, Siv reflects on her own passing thoughts, calling them “almost a poem.” The self-consciousness is a right fit for her character, someone longing for romance and escape, but never able to achieve either.

Furmark also gives glances of Siv’s diary and, when discovered by the snooping Peter, Ulrik’s, imbuing the passages with distinct verbal qualities linked not just to the characters but to their specific letter-like reveries. The contrasts are further heightened by an excerpt from a published book of poetry and the song lyrics Marita sings to herself. Furmark also achieves subtleties in her dialogue, as when Borje complains to Siv about all of the competing Communist parties, “we should stick together … instead of splintering up all the time,” while unaware that his wife is about to leave him. Like Furmark’s inks and watercolors, her word palette is equally striking despite its surface casualness.

Much of the novel’s work is accomplished between chapters, with key scenes and ultimately the story’s saddest outcomes occurring off-page, requiring readers to imagine what is only glancingly referenced while Marita and her best friend wander outside in their rainboots. It’s an especially apt approach for a graphic novel since the comics form is largely defined by the content implied between each of its juxtaposed images. So again, Furmark demonstrates the excellence of her art. Red Winter is a window into not only Sweden of the 1970s, but to an alternate comics tradition defined by subtle craft and storytelling.

I look forward to more of Furmark’s translations.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Anneli Furmark, Red Winter

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

14/01/19 Clarifying Closure

My article “Clarifying Closure” appears in the latest issue of the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics (which is available here). In it, I suggest several categories of inferences to account for the broader concept of closure, the mental leaps needed to conceptually connect two physically connected images:

Recurrent: images reference a shared subject.

Spatial: images share a diegetic space.

Temporal: images share a diegetic timeline.

Causal: a common quality of temporal closure in which an action is understood to have occurred between images.

Embedded: an image perceived as multiple images.

Non-sensory: non-spatiotemporal differences between representational images.

Associative: dissimilar images represent a shared subject.

Gestalt: images perceived as a single image interrupted by a visual ellipsis.

Pseudo-gestalt: discursively continuous but representationally non-continuous images.

Linguistic: images relate primarily through accompanying text.

The article includes illustrated examples by Leigh Ann Beavers and lists a range of actual comics that contain further examples. I would like to follow-up on those.

First, I offered an earlier, shorter list of four types of closure a couple of years ago, with an example from Watchmen here.

More recently, I wrote about (mostly) spatiotemporal closure using photographs here (I also introduce the alternate term “hinge”).

Leigh Ann and I are currently drafting a textbook for Bloomsbury to be titled “Creating Comics,” which will feature art from students in our comics class. Below are eight of their closure (or, as I say in the textbook, “hinge”) examples to further clarify the above categories.

1. Emily juxtaposes two identical images. The spatial hinge is obvious: we’re looking at the same cube on the same shelf from the same angle. The temporal hinge is harder. How much time passed between the images: an hour, day, minute, week, second, month? Or did no time pass, and the images are the same because they show the same moment? Or how do we know the second image doesn’t happen first in the story world and the images are arranged to reverse chronology? Technically we don’t, but comics norms imply a forward movement in time—unless something drawn prevents that assumption.

2. Emily’s second pairing repeats the same spatial hinge, and though it’s still ambiguous how much time passes between them, the appearance of a hand means that the two images are not showing the same moment. A causal hinge also explains why the block is gone in the second image: after grabbing it (as drawn in the first image), the hand then removed it (not drawn), leaving the shelf empty (drawn in the second).

3. Mims’ first two panels use spatial, temporal, and causal hinges too. We don’t know how far apart the sidewalk in the first panel and the sand in the second are, but we infer they’re in walking distance and that minutes pass between them. We also assume that the person wearing the shoes in the first panel removed and discarded them during that same period of time. We make similar inferences between the second and third panels—though note the addition of a gestalt hinge: the water line appears at the bottom of the second panel. So spatially the second and third panels are continuous—though time passes between them to allow the figure to have stepped into the water. An astute viewer might also notice that the figure’s shadow changes—in ways that could confuse things and so might then be ignored, either consciously or unconsciously.

4. Anna draws a figure on a bed surrounded by giant, writhing centipedes. Though it’s possible to see this as a single image, the bed is more likely a panel inset placed “over” the image of the centipedes—which, if understood as a close-up, means the centipedes aren’t giant. Though the centipedes could exist somewhere in the same room as the bed, the spatial hinge is ambiguous. That’s because the centipedes are most likely not real. This is the dreamed or otherwise imagined fear of the figure in the bed—and so an example of a non-sensory hinge.

5. Hung draws no panel frames, and so his image has no gutters either. Is this an image of three players practicing soccer? Probably not. First, all three are drawn so similarly, they create a recurrent hinge. Plus each figure implies a different angle of perspective on the undrawn field or fields, and so three different moments in time. Though the figures overlap and are in a sense one image, they create the impression of three images through embedded hinges. Notice that the third figure includes a half-outline, a kind of partially embedded image that suggests movement. But if it’s understood as a blur—like the movement lines of the ball—then it’s experienced as one moment in time and so is not embedded.

6. The corner of a house viewed from outside and an off-centered close-up on an interior doorknob–how do these relate? Presumably they’re parts of the same house—but why are they side-by-side? Any spatial hinge doesn’t tell us much. But if you read Coleman’s two captions, the images take on a clearer relationship, including the presence of multiple undrawn characters at the center of the story. But without the words there is no story. The images relate primarily through linguistic hinges.

7. Lindsay’s two images require a spatial hinge to understand that the second is a close-up of the driver operating the car in the first. Though a temporal hinge might suggest either two consecutive moments or a single moment, the effect is roughly the same. More interestingly, she lines up the edges of the road to the edges of the driver’s head, creating a pseudo-gestalt effect. The road and head have no close spatial relation within the story, but they’re drawn as though they’re connected—suggesting something about the driver’s character too. Since Lindsay uses no gutter, just a single line framing and dividing both images, the pseudo-gestalt hinge is even stronger. She also draws the driver’s sunglasses breaking the second frame, further connecting the two images.

8. Finally, Grace connects her two panels with a gestalt hinge. It’s as if the gutter interrupts a single image, imposing a break where we understand there is none in the story world. Though the story context would tell us more, the half-empty picnic blanket in the left panel and the lone figure on the right are suggestive—more so than if the gutter didn’t highlight her isolation and imply the absence of someone beside her.

Of these categories, I think pseudo-gestalt is the newest concept and so least explored. Here’s the earliest example I’ve found yet, from a 1918 Krazy Kat by George Herriman:

Notice how the figure apparently divided by the gutter between the third and fourth panels is actually from two different locations at two different points in time. It’s only the framing arrangement that creates the effect of a semi-unified figure. This is possible because the character is moving from right to left within the story world while the viewer’s reading path is from left to right.

Notice how the figure apparently divided by the gutter between the third and fourth panels is actually from two different locations at two different points in time. It’s only the framing arrangement that creates the effect of a semi-unified figure. This is possible because the character is moving from right to left within the story world while the viewer’s reading path is from left to right.

And, just because they’re fun, here are two more, non-comics examples of pseudo-gestalt. Each is created by the juxtaposition of two otherwise unrelated images. There’s even a gutter:

Tags: Scott McCloud

- 6 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

07/01/19 Intro to Graphic Novels

I’m teaching a new course this semester, Intro to Graphic Novels. Where to start is always a hard question, especially given the messiness of comics history. Usually terminology adds clarity, but the opposite can be true for comics because so many of the terms overlap and contradict. Which also makes it a good place to start. Here are some of the main terms, with some quick historical explanations. Instead of the usual alphabetical order, I’m trying a chronological approach. Also, I seem to be using a Jeopardy question format–not sure why. This is of course a work-in-progress …

What is a “cartoon”?

Beginning in the 1600s, the term referred to the cardboard-like material artists used for preliminary sketches. After the satirical magazine Punch published a set of mock architectural sketches for a planned parliamentary building in 1843, a “cartoon” meant a humorous illustration drawn in the simplified and exaggerated style of caricature. Here’s a 1847 Punch political cartoon satirizing the U.S.:

Some cartoons included more than one image (which also makes them comics according to the definition below). This is a racist, anti-Irish, anti-Chinese, anti-immigration cartoon from 1860:

What is a “comic”?

In the 19th century, a “comic” referred to humor magazines that published prose-only stories and cartoons. The term transferred to newspaper cartoon sections in the late 1890s and was synonymous with “funnies” or “funny pages,” which described the genre, but not the form. “Comics” now refers to the form, but not the genre. There is no single accepted definition, but most scholars agree that a comic is a sequence of juxtaposed images. Here’s Scott McCloud’s definition from his 1993 Understanding Comics:

What is a “comic strip”?

Comic strips were originally vignettes told in a strip of cartoon images, so the term combined genre and form. Though there are many forebears, comic strips first achieved major popularity in the 1890s. The first did not appear in individual strips, but most evolved that way by 1913, especially those printed in daily newspapers, like George Herriman’s Krazy Kat:

Strips didn’t always appear in horizontal strips. Herriman sometimes worked in double rows:

Sometimes in columns:

And Sunday comics continued to be larger than strips, often with one comic to an entire page:

What is a “comic book”?

Originally a collection of comic strips published in book form, a comic book later referred to individual issues of a series, typically published monthly. A series is called a comic book too. The 1934 Famous Funnies established the standard size for American comic books, but the term was in use since 1904.

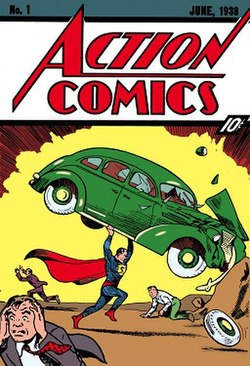

Action Comics made the form massively popular in 1938:

What is a “graphic novel”?

The term emerged in the 1960s and 1970s in attempt to differentiate book-length works in the comics form that were also not in the popular children’s comics genres of humor and action. Although a prose-only novel refers to the genre of fiction, a graphic novel may indicate form regardless of whether the content is fiction or nonfiction. Will Eisner used the term for his 1978 Contract With God:

What is a “graphic narrative”?

A term that combines graphic fiction and graphic nonfiction, which includes graphic memoir and graphic journalism. Though not the first, Art Spiegelman’s Maus established the category of graphic nonfiction when he wrote to the New York Times requesting that it be moved from the fiction to the nonfiction bestseller list in 1991 (it won a Pulitzer the following year). Though the term graphic narrative addresses the ambiguity of graphic novel, not all comics are necessarily narratives. Abstract comics and poetry comics are examples.

What is “bande dessinée”?

The French term for comics, literally “drawn band,” and so a more accurate term than “comic strip.” Herge’s 1940s Tintin is one of the best known:

What is “fumetti”?

The Italian term for comics, literally “little clouds of smoke,” meaning speech balloons. Many fumetti are also photo-based, so fumetti is sometimes synonymous with photocomics.

What are “word containers”?

There are several kinds. Traditionally character speech is contained in circles called balloons. They usually include pointers. Thought bubbles contain internal speech. Remote narration and other kinds of non-speech are typically placed in caption boxes without pointers.

What is an “image”?

There are two kinds: representational and abstract. The first is a drawing of something; the second is not representing anything visual beyond itself. A representational image has two elements: a) what is drawn (the subject matter), and b) how it is drawn (the style).

What is “style”?

An artist’s consistent tendencies for representing but also altering subject matter, including qualities of line and shape.

What is “encapsulation”?

The selection of moments of a story that are represented in images, leaving other moments undrawn but implied.

What is “closure”?

Inferences about undrawn story content, usually implied by juxtaposition.

What is “juxtaposition”?

Any two images arranged side by side are juxtaposed.

What is a “panel”?

An image in a comic. Traditionally panels are predominately rectangular and enclosed by a frame and separated from other panels.

What is a “frame”?

Actual frames are physical objects that contain paintings or other two-dimensional art. A frame in a comic is only a drawing of a frame and so, unlike actual frames, is part of the image.

What is a “gutter”?

The negative space between images. If the background is undrawn, the gutters will appear blank. If the images are rectangular, the gutters will appear vertical and horizontal.

What is an “inset”?

A panel placed as if overtop or within the space of a larger image.

What is “layout”?

The arrangement of images on a comics page.

What is a “reading path”?

The specific order images are to be viewed, usually implied by the layout. The most common kinds of paths are Z-paths (from left to right in rows), N-paths (from top to bottom in columns); paths that use a combination of rows and columns. Manga, of course, read right to left.

What is a “script”?

A prose description of planned image content, including the words to be lettered into the final artwork. The script is not part of the eventual comic.

What is “diegesis”?

From the Greek word for narrative, diegesis is an academic term for story. Diegetic is the adjective form referring to anything within the story world.

What is “discourse”?

The term is useful for separating the world, events, and experiences of characters from how a reader or viewer experiences them through the medium of a comic. Characters in the story world aren’t aware of the reading paths, layouts, frames, gutters, word containers, styles, and any other qualities of the discourse that creates them.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized