Monthly Archives: September 2016

29/09/16 My Superhero Dream Team (I Made This!)

When Ryan Stills at Invaluable.com asked me about my “superhero dream team,” he probably didn’t have this in mind: a real-world team based on actual superhumans, AKA Olympic athletes. As some of you may recall from past posts, I designed two of these in August, and three more have just joined their ranks.

I’ve revealed the secret identities of those original two Olympians already, but the other three remain masked. So consider this a test for whether superheroes really could keep their alter egos a secret just by stretching a little spandex across their faces. If anyone can unmask all five, I’ll mail you a copy of my book “On the Origin of Superheroes.” I’ll even cover the mailing cost because, to be honest, one of them is a bit of a mystery to me too.

So now here’s the team:

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

26/09/16 Top 8 Superhero Comics, 1971-2000

It’s hard leaving out some of my personal favorites (no Sienkiewicz!), especially from my own childhood and college years, but these ongoing lists are for my book “Superhero Comics,” and my editor wants the genre’s “Key Works.” Which sometimes overlaps with “stuff Chris loves” and sometimes doesn’t. I’m also keeping the focus on the authors, and that means defining a “work” by writers and artists (usually penciller). Also, to prevent someone like Alan Moore from hogging half the slots, I’m trying to impose a one-work-per-author rule. The Comics Code was revised in 1971, the first revision since it was created in 1954, and then revised again in 1989, so those are my historical markers.

Second Code Era, 1971-1988:

Claremont & Byrne’s The Uncanny X-Men (1977-81).

Chris Claremont has the longest run on any comics title. After Len Wein and Dave Cockrum’s one-issue reinvention of the series, which had been reprinting 1960s issues since #67 (December 1970), Claremont wrote The Uncanny X-Men from #94 (August 1975) to #279 (August 1991), as well as numerous spin-off titles including New Mutants, Wolverine, and X-Men #1 (October 1991), the highest selling comic book of all-time. John Byrne pencilled and often co-wrote #108 (December 1977) – #143 (March 1981), before moving on as writer-artist of a wide range of Marvel and DC titles including Alpha Flight (1983) and the Superman reboot mini-series The Man of Steel (1986). Byrne further developed the Adams-influenced visual style that would continue to define superhero comics for the next decade, and Claremont’s long-term approach to multi-issue plotting and characterization became increasingly standard. Claremont and Byrne’s joint run includes the X-Men’s most acclaimed narrative arc, The Dark Phoenix Saga, #129-138, ending with the death and funeral of Jean Gray—events Bryne would help to retcon out of existence during his five-year run of The Fantastic Four in 1986. Instead of Byrne, Claremont initially partnered with Neal Adams for God Loves, Man Kills (1982), one of the first graphic novels published in the Marvel Graphic Novel format, but because Adams refused a standard work-for-hire contract, Marvel replaced him with Brent Anderson. Byrne returned to Marvel in the late 80s to work on several titles including West Coast Avengers and Sensational She-Hulk, after which he wrote creator-owned titles for Dark Horse Comics.

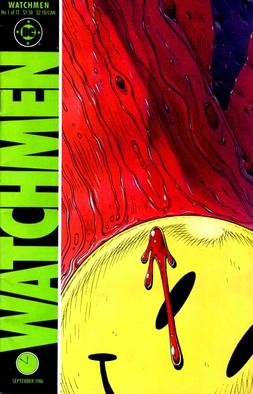

Moore & Gibbons’ Watchmen (1986-87).

The most acclaimed superhero comic of all-time, the twelve-issue Watchmen, along with Frank Miller’s four-issue The Dark Knight Returns (1986), marks a major turning point in the genre, with a leap in psychological realism and a rejection of the Code-mandated triumph of absolute good over absolute evil. Moore initially plotted the series with characters DC had recently acquired from the defunct Charlton Comics. When editors objected, he and Dave Gibbons nominally redesigned the cast, creating morally flawed counterparts that interrogate the decades-old norms of the superhero character type. Because the series stood apart from the rest of the DC universe, Moore and Gibbons received unusual creative freedom, and the limited series format also enabled them to work in a closed narrative form that barred sequels, a rarity in comics at that time and a major factor in the series’ excellence. Time magazine listed Watchmen in its one hundred best English-language novels published since 1923 (Grossman 2010). Moore’s other major works include Marvelman / Miracleman (1982-89), V for Vendetta (1982-88), The Saga of the Swamp Thing (1984-87), From Hell (1989-96), and The League of Extraordinary Gentleman (1999-2003).

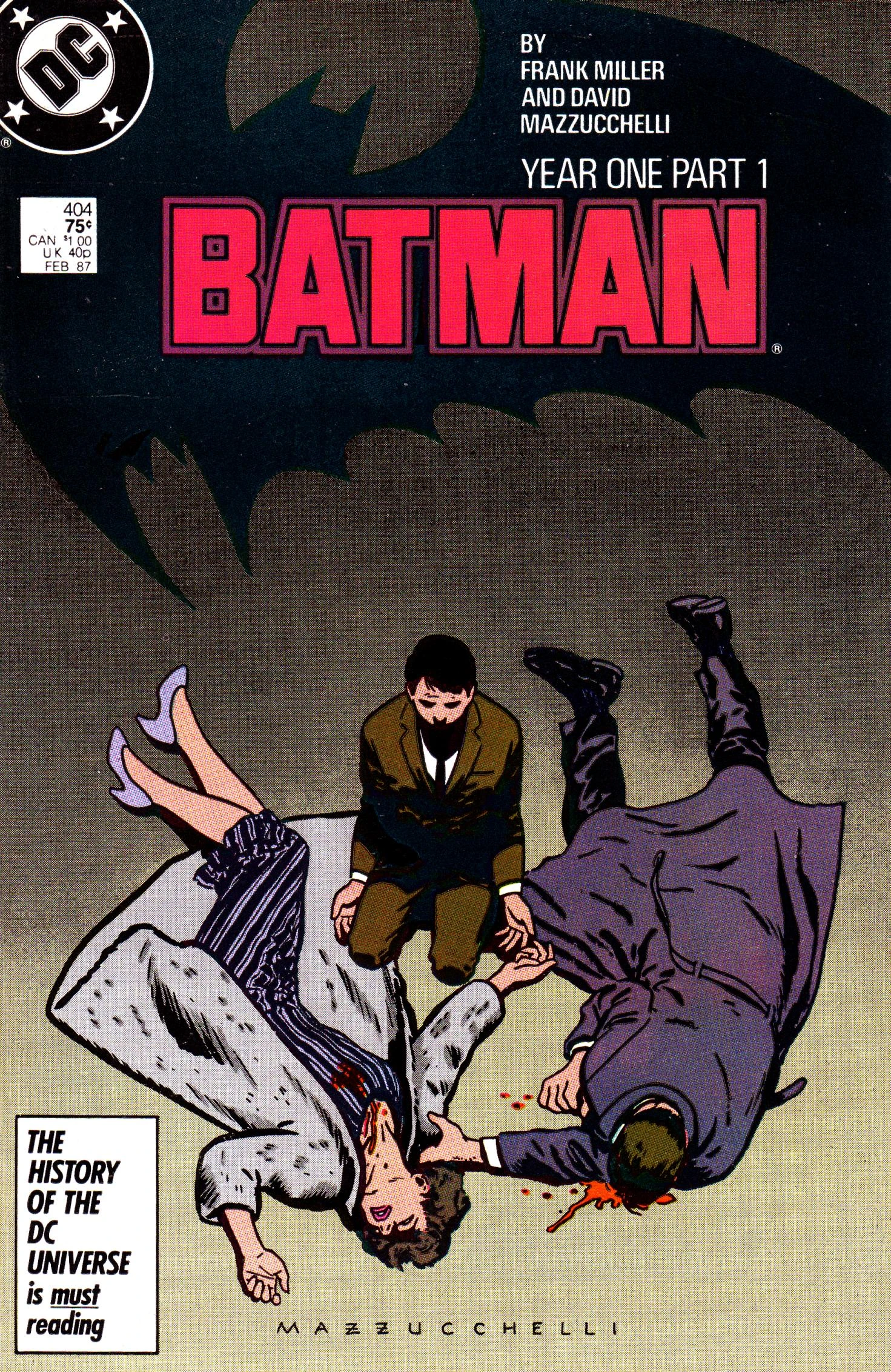

Miller & Mazzucchelli’s Batman: Year One (1987).

Following the successes of his first Daredevil run (1979-1983), Ronin (1983-84), and The Dark Knight Returns (1986), Frank Miller partnered with artist Bill Sienkiewicz for the graphic novel Daredevil: Love and War (1986) and the limited series Elektra: Assassin (1986-87) and penciller-inker David Mazzuchelli for the 1986 Born Again arc in Daredevil and DC’s history-redefining Year One arc in Batman #404 (February) – #407 (May 1987), ending Miller’s most productive period with DC and Marvel, after which he began publishing with Dark Horse. Year One, Born Again, and The Dark Knight Returns are widely regarded as Miller’s best work. Born Again, however, is marred by a literal deus ex machina ending, and though less genre-influencing than the fascist-leaning Dark Knight Returns, Year One’s time scope pushed Miller into storytelling innovations where John Byrne’s parallel The Man of Steel suffers in contrast. Unlike the sometimes cartoonish excesses of Miller’s Dark Knight Returns art, Mazzuchelli’s comparatively sparse style provided a realistic baseline rendered in short, grainy lines for the series’ much praised gritty effect. Mazzuchelli soon left superhero comics, publishing an adaptation of Paul Auster’s postmodern detective novel City of Glass in 1994 and the even more highly acclaimed Asterios Polyp in 2009.

Gaiman’s The Sandman (1988-1996).

Gaiman’s The Sandman (1988-1996).

Neil Gaiman entered comics as a fan of Swamp Thing and then as a journalist, interviewing Alan Moore and other creators for a 1986 Sunday Times Magazine article that was never published because the editor was expecting a Wertham-esque critique of the industry (Gaiman 2016: 265, 233). DC first hired him for the 1987 Black Orchid limited series with the Sienkiewicz-influenced artist Dave McKean, after which Gaiman requested Sandman, a minor and largely forgotten superhero created by Gardner Fox and Bert Christman in 1939 and briefly reinvented by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby in 1974. Working with a wide range of artists including McKean for covers, Gaiman wrote the entire series, from #1 (January 1989) to the final #75 (March 1996), creating one of DC’s most popular titles of the 90s and drawing acclaim and readership from outside traditional comics audiences. Reprint compilations sold well in trade paperback formats, expanding readership beyond direct market comic shops to general bookstores. Though the title began before DC instituted its creator-owning imprint Vertigo in 1993, Gaiman retained copyrights, and when he left the series, it and its characters were not continued. Gaiman moved from comics to a highly successful and ongoing career in literary speculative fiction.

Third Code Era, 1989-2000:

Morrison & McKean’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth (1989).

The term “graphic novel” emerged in the 70s, and Marvel published “Marvel Graphic Novel” and “Epic Graphic Novel” imprints in the 80s that featured stand-alone works rather than collected reprints of pre-existing series. “DC Graphic Novel” used the same trade paperback format, but Arkham Asylum, published the October after the summer release of Tim Burton’s Batman film, was one of the first graphic novels printed in hardback—then a norm of non-comics literary publishing. It soon became one of DC’s best-selling graphic novels. Writer Grant Morrison had joined DC a year earlier, reviving the character Animal Man in a limited and then ongoing series and then Doom Patrol in early 1989. When DC assigned Arkham to artist Dave McKean, Morrison revised his original 48-page script into a 67-page, screenplay-like format, giving McKean greater freedom for his expressionistic paintings, which expanded to 120 pages. Morrison later worked on a wide range of superhero titles, including his own creator-owned The Invisibles (1994-2000).

McFarlane’s Spawn (1992).

Because Marvel refused to share copyrights, a prominent group of creators, including Spider-Man artist Todd McFarlane and X-Men writer Chris Claremont, left the company to form Image Comics in 1992. Spawn #1 (May 1992), one of Image’s first publications, was a top-selling superhero comic of the year, drawing new attention to independent publishers in the Marvel-DC dominated market. Image joined Eclipse, which had formed in the late 70s and was publishing Alan Moore’s and briefly Neil Gaiman’s Miracleman, and Dark Horse, which had formed in 1986 and featured Paul Chadwick’s Concrete and soon Mike Mignola’s Hellboy. Image Comics, distributed entirely through the increasingly dominant direct market system, never joined the Comics Magazine Association of America and so Spawn and its other titles were never subject to the Comics Code. Though McFarlane partnered with various guest writers, including Moore and Gaiman, their contributions are largely forgotten, and Spawn is remembered primarily for its impact on the wider industry. McFarlane, along with fellow Image artists Rob Liefeld and Jim Lee, also defined the hypermuscular and hypersexualized style of the 90s. Despite its emphasis on creator rights, Image, using the work-for-hire argument Marvel used against Jack Kirby, claimed full copyright of the character Angela co-created by Gaiman and McFarlane and introduced in Spawn #9 (March 1993). Gaiman won a lawsuit against Image in 2002, after which McFarlane relinquished his rights and Gaiman sold the character to Marvel where Angela was introduced in 2013.

![]() McDuffie & Bright’s Icon (1993-97).

McDuffie & Bright’s Icon (1993-97).

Another independent publisher, Milestone Comics formed in 1993 but in a distribution partnership with DC with both company logos appearing on covers. Milestone consisted entirely of African American creators who retrained ownership and creative control of their work. Dwayne McDuffie wrote or co-wrote all four of the initial titles, including Icon, penciled M. D. Bright, who, like McDuffie, had worked on previous superhero titles for DC and Marvel. The two collaborated on all but five issues of the complete run, #1 (May 1993) to #42 (February 1997). The series features a Superman-like hero who, instead of landing in the 20th century mid-west to be raised by white farmers, lands in the Antebellum South to be raised by an enslaved plantation worker. His Robin-like sidekick, Rocket, is black teenager whose out-of-wedlock pregnancy and motherhood are central themes of the series. The series is widely praised for bringing a diversity of accurately portrayed black characters to superhero comics. Icon ended when the market collapse of the mid-90s drove Milestone out of the comics business.

Waid & Ross’ Kingdom Come (1996).

Waid & Ross’ Kingdom Come (1996).

The limited series Kingdom Come, #1 (May 1996) – #4 (August 1996), was co-written by Mark Waid and Alex Ross and painted by Ross. As an Elseworld imprint, the story features a wide range of DC superheroes, but outside of company continuity, enabling Waid and Ross to freely interpret and in some cases kill characters in a plotline involving the morally indifferent children of today’s heroes. Ross conceived the story while working with writer Kurt Busiek on the similar, four-issue Marvels (1994), and DC teamed him with Alex Waid, who had written for range of Marvel and DC titles, including Captain America and The Flash. The work is most significant for marking the highpoint of photorealism in the genre. In contrast to the comparably cartoonish standards of the period, Ross worked from live models and, instead of following the pencils-inks-colors process norm of the industry, painted in his preferred medium of opaque watercolors. While Bill Seinkiewicz and Dave McKean had achieved similar moments of painterly photorealism, Ross maintained the style across his work. Due to the labor intensiveness of the approach, he produced mainly cover art after Kingdom Come.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

19/09/16 Top 8 Superhero Comics, 1934-1971

While there is no definitive canon for superhero comics, I’m working on a chapter for my forthcoming book that presents a list of “key works.” I’m defining “key” by a variety of elements including aesthetic quality, historical impact, and medium innovation. In terms of genre, a work’s influence on other creators is as noteworthy as its merits judged individually. Some works listed here are historically significant to the genre, some are individually excellent, and some are both. While a comics text might include anything from a single comic strip to a collected comic book series to a graphic novel created and published as a single work, I define and so divide texts according to authorship, usually writer-artist collaborations on a single series. When an ongoing comic book title changes authors, it also changes texts. While a complete list of key works might number into the hundreds, I’m imposing practical limits, selecting only four works from each of the six Code-defined historical periods. Here are the first eight:

Pre-Code Era, 1934-1954:

Siegel & Shuster’s Superman in Action Comics and Superman (1938-1940).

After premiering in Action Comics #1 (June 1938), the original incarnation of Superman was relatively short-lived. Jerry Siegel continued to write the character, but due to his failing eyesight co-creator Joe Shuster was no longer a primary artist after the second year. Shuster penciled and inked the Superman episodes in Action Comics #1-#5, penciled and co-inked #6-10, and then penciled or co-penciled all but three issues of #11-24 (May 1940), after which he contributed only sporadically. After the initial Superman July 1939 reprint edition, he penciled the entire 64-page quarterly Superman #2 and #3 (March 1940). Shuster’s run coincides roughly with Superman’s first arch-nemesis, the Ultra-Humanite, retconned in #13 as the mastermind behind Superman’s first year of adventures, seemingly killed in #21, and replaced by Luthor in #23. Shuster however retained some artistic control by subcontracting replacement artists himself through his “Shuster Studio.” Siegel and Shuster formally left DC, then National Allied Publications, after their ten-year contract expired and they lost their suit against the company for copyright of Superman.

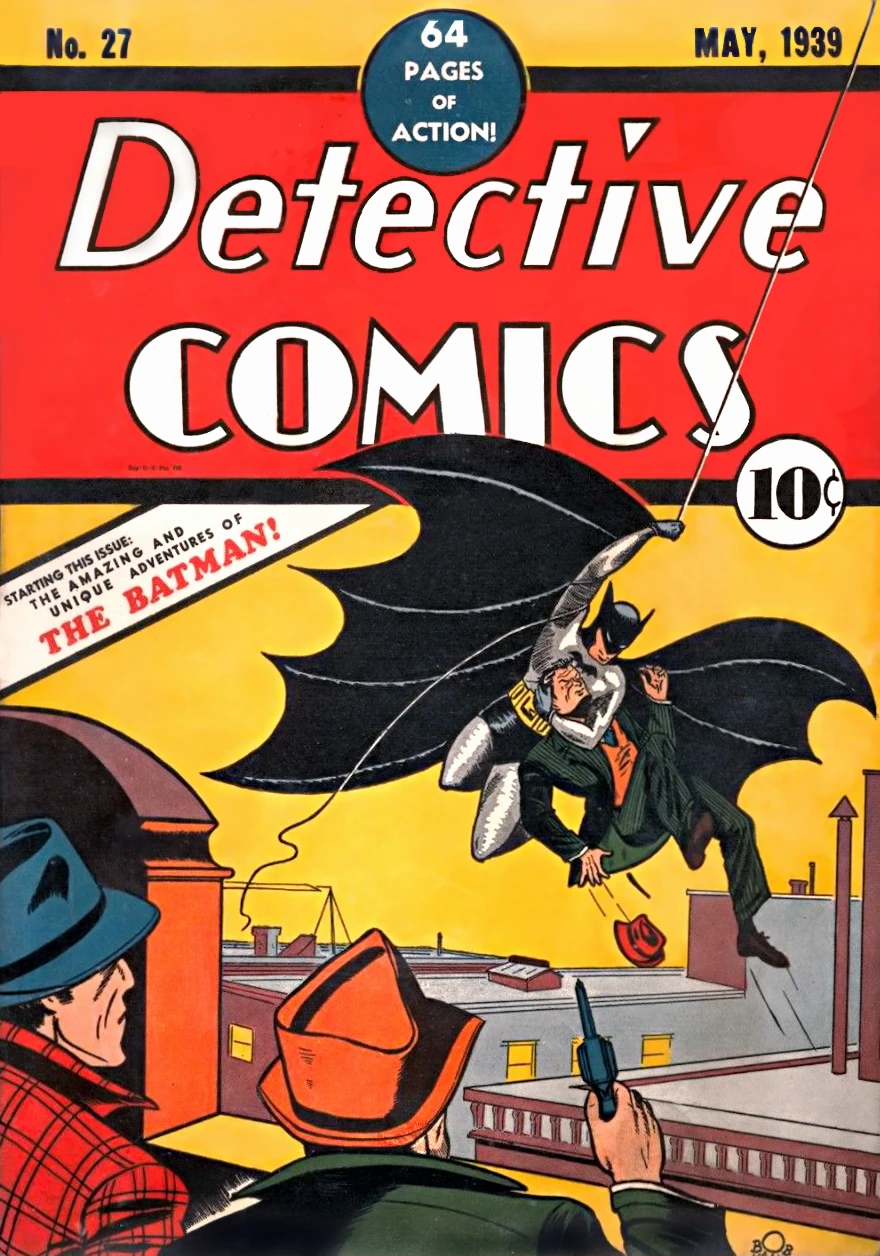

Finger & Kane’s Batman in Detective Comics and Batman (1939-1943).

Because writer Bill Finger was employed by artist Bob Kane who alone was contracted by Detective Comics, Inc., Kane received sole creator and author credit for Batman. Though Finger appears to have been the primary creator, he wrote only the first two episodes before Gardner Fox’s six-issue run from #29-34, which introduced discordant supernatural and fantastical elements that Finger eliminated upon his return in #35. Kane and Finger’s partnership and creative control of the character ended through attrition. Finger wrote all of the Batman episodes in Detective Comics from #27-28, 35-59, seven of 60-68, and then only four of the next seventeen issues, leaving the series after #85 (March 1944). Kane penciled all but one issue from #27-74 and then four of the next eight, leaving the series after #82 (December 1943). Kane exclusively penciled the multi-story Batman #1-8 (December-January 1941), and Finger wrote all of #1-10 (February-March 1942). Batman #14 (December-January 1942) was the first without a story by Finger and #19 (April-May 1943) the first without art by Kane, after which both creators became increasingly rare. Finger wrote for a range of other DC titles, and Kane maintained credit for Batman after renegotiating his contract in 1949.

Eisner’s The Spirit (1940-1942).

In 1939, Will Eisner left his comics studio partnership with Jerry Iger to manage a 16-page tabloid-sized insert for Sunday newspapers distributed by the Register and Tribune Syndicate. Unlike almost all other pre-1980s creators, Eisner negotiated ownership of his work and received wide artistic freedom. The first insert was published on June 2, 1940 and featured the first seven-page The Spirit episode written, penciled, and inked solely by Eisner. Initially a police detective, Denny Colt is seemingly killed and buried but returns to fight crime under a mask and alias. Eisner had created and co-created previous comic-book heroes, including the Flame, Dollman, Blackhawk, and the copyright-infringing Wonderman, but The Spirit provided the opportunities for innovation that would establish Eisner as a central pioneer of the comics medium. Beginning May 3, 1942, Eisner, now serving overseas in the military, turned co-pencils and inks over to ghost artists and scripts to ghost writers beginning June 7. He contributed sporadically during the war, returned as the primary writer on December 23, 1945, and as primary artist January 12, 1947. His writing contributions decreased again in 1949 and his art in 1951, until he was primarily only supervising when the series ended October 5, 1952.

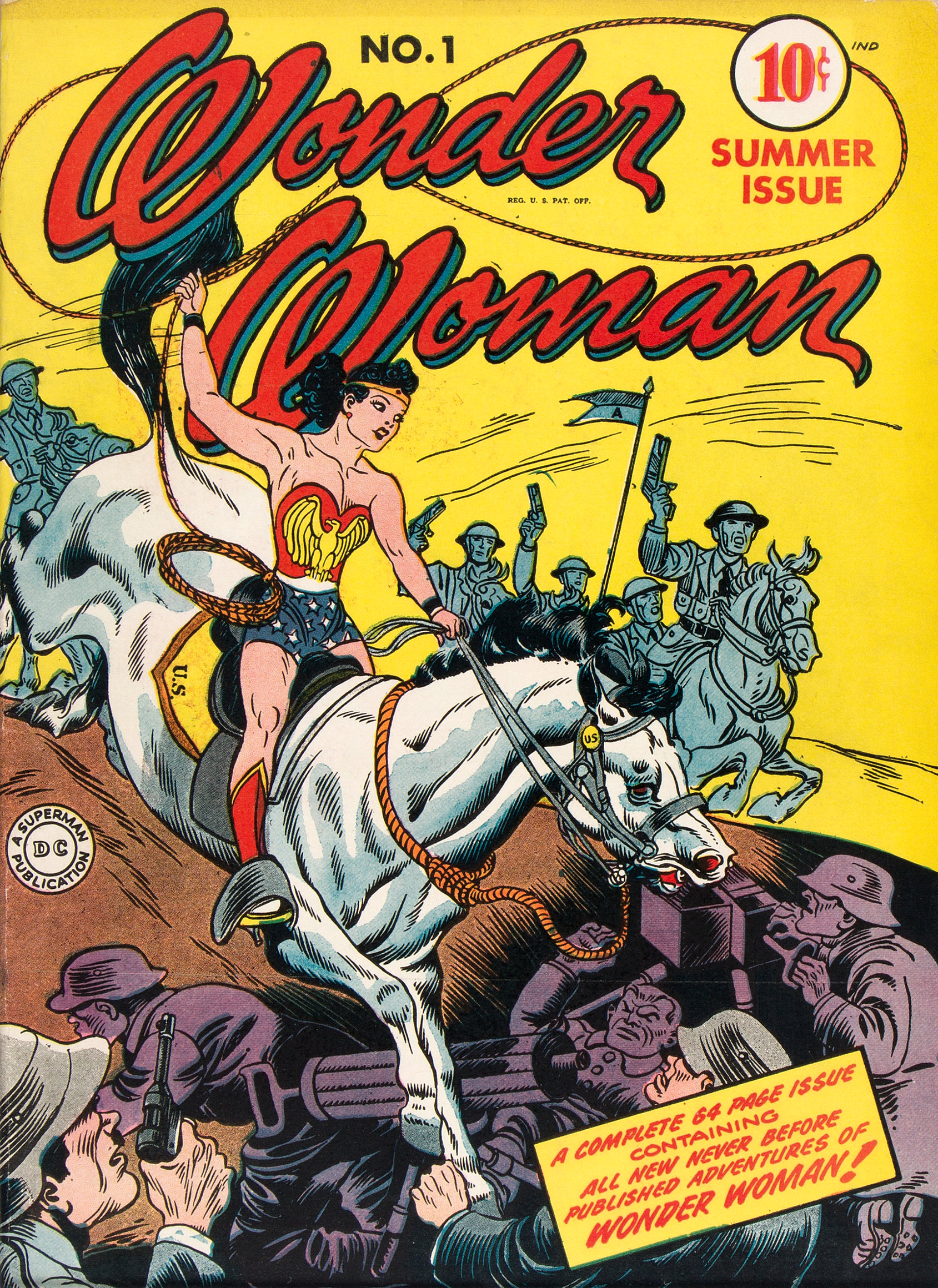

Marston & Peter’s Wonder Woman in All Star Comics, Sensation Comics, Wonder Woman, and Comics Cavalcade (1941-1948).

Wonder Woman was conceived by psychologist William Moulton Marston, who selected Harry G. Peter as artist and credited their collaboration under the joint pseudonym Charles Moulton. Marston also served on publisher M. C. Gaines’ advisory board for All American Comics, a sibling company to Detective Comics and National Allied Publication, later jointly known as DC. Wonder Woman premiered in All Star Comics #8 (December 1941), on sale during the bombing of Pearl Harbor, before expanding to Sensation Comics (January 1942), Wonder Woman (Summer 1942), and Comics Cavalcade #1 (December 1942). Marston’s run is notorious for themes of BDSM, which he intended to be instructional for young readers because he believed that sexual bondage—pleasurable submission to another’s loving authority—was central for conditioning good citizens. Marston died in 1947, but his writing continued to appear until Robert Kanigher officially replaced him on Wonder Woman #31 (September 1948). Peter continued on the series until his own death, with his last pencils and inks appearing in #97 (April 1958). With Superman and Batman, Wonder Woman is one of only three superhero characters in continuous publication since their pre-World War II premieres.

First Code Era, 1954-1971:

Lee & Kirby’s The Fantastic Four (1961-70).

Lee & Kirby’s The Fantastic Four (1961-70).

Former Iger Studio employee Jack Kirby established himself as a major comics artist during World War II, most famously co-creating Captain American with Joe Simon in 1941 for Marvel’s predecessor, Timely. Kirby and Stan Lee’s nine-year run on The Fantastic Four, from #1 (November 1961) to #102 (September 1970), is likely the longest continuous collaboration on a single title in comics history. The first issue marks publisher Martin Goodman’s transition from the financially struggling Atlas Comics of the 50s to the soon market-leading Marvel of the 60s. The series redefined the superhero genre, while also retroactively exposing authorial and legal ambiguities that run to the core of the industry. Though Lee received sole writing credit, Kirby not only penciled but often produced storylines and drafted captions and dialogue independently, creating such characters as the Silver Surface without Lee’s prior input. Kirby died in 1994, and his estate filed for copyright termination for the characters that Kirby co-created. Marvel sued, arguing that he had been contracted on a work-for-hire basis. The Supreme Court was preparing to hear the case in 2014 when the recently Disney-purchased Marvel Entertainment settled out of court for an undisclosed sum. Had the Court ruled in favor of Kirby’ heirs, not only would Marvel’s blockbuster film franchise have been affected, but the precedent would have threatened all of Warner Brother’s DC copyrights too. Lee continued writing the series for a year following Kirby’s departure to DC in 1970, leaving the series after #115 (October 1971).

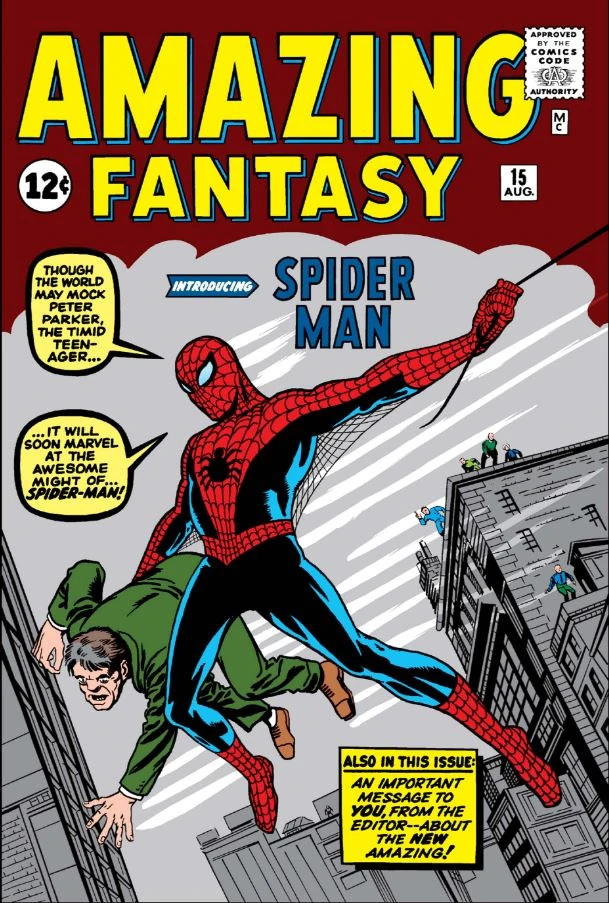

Lee & Ditko’s Spider-Man in Amazing Fantasy and The Amazing Spider-Man (1962- 66).

Although Kirby drew the first sketches of the character, Lee chose to collaborate with Steve Ditko, who had been working with Atlas/Marvel since 1955. Martin Goodman had little faith in the character, largely because teenagers were typically cast as sidekick not lead heroes, slotting the original eleven-page episode in the series-cancelled Amazing Fantasy #15 (August 1962). Increased sales however allowed Lee to reintroduce the character six months later in a new title, The Amazing Spider-Man #1 (March 1963), which has run continuously since. Ditko penciled and inked every issue through #38 (July 1966), after which he left Marvel for Charlton Comics. By the end of their collaboration, tensions between Lee and Ditko grew so high that the two reportedly no longer communicated directly, with Lee receiving Ditko’s completed artboards through a third party. Unlike Kirby, Ditko objected to Lee’s so-called Marvel Method in which pencillers worked without scripts and so assumed uncredited and uncompensated writing duties. Lee continued officially to write the series until #110 (July 1972).

Jim Steranko’s Strange Tales, Nick Fury: Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., and Captain America (1967-69).

Jim Steranko applied for a position at Marvel in 1966 and, after auditioning by inking two unused pages of Jack Kirby’s original 1965 Nick Fury draft (Steranko 2013: 330-1), Stan Lee assigned him to “Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.” in the split-feature Strange Tales. Steranko inked Kirby’s twelve-page layouts for #151-153 and then wrote and produced all art from #154 (March 1967) to #168 and, when the series switched to twenty-page installments, #1-3 and #5 (October 1968) of its own title. After producing the covers for #6 and #7 (based on Salvador Dali), he created Captain America #110, #111, and #113 (May 1969), which featured crossover appearances by H.Y.D.R.A. and Nick Fury. Though Steranko’s total output was modest and, as evidenced by others’ fill-in work for Nick Fury #4 and Captain America #112, not always produced on deadline, his art was the most innovative since Will Eisner’s in the 1940s, overturning the layout norms set by Kirby during the preceding decade. Steranko however disliked the editorial changes Lee sometimes imposed. On #111, for example, a panel sequence was to read counter-clockwise, but Lee reordered the talk balloons so the images and dialogue contradict in the published version (Lee, Kirby & Steranko: 2014: 217, 280). As a result, Steranko produced only cover art for Marvel titles into the early seventies.

O’Neil & Adams’s Green Lantern Co-Starring Green Arrow (1970-72).

Neal Adams began his comics career illustrating newspaper strips in the early sixties, before starting at Warren and DC in 1967 and Marvel in 1969. Dennis O’Neil began as a writer at Marvel in 1966, before moving to Charlton and then DC where he famously reinterpreted Wonder Woman by eliminating the character’s powers and iconic costume in 1969. Like Steranko, Adams and O’Neil are often cited in the transition from the Silver to the Bronze Age. They first worked together on two issues of X-Men and two issues of Detective Comics published at the start of 1970, but they are remembered for their redesign of Green Lantern, which beginning with #76 (April 1970) included Green Arrow. Though Adams’ layouts are often as innovative as Steranko’s, his longest-lasting influence is the comparably photorealistic style he brought to the genre: “If superheroes existed, they’d look like I draw them” (Smith 2011). O’Neil brought a similar level of realism to the series by portraying Green Lantern outgrowing the naïvely simplistic understanding of good and evil that had defined superhero morality since the 1930s. After the title was cancelled with #89 (May 1972), the series finished as a back-up feature in four issues of Flash.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

12/09/16 “The Ten Best Issues of Comic Books”

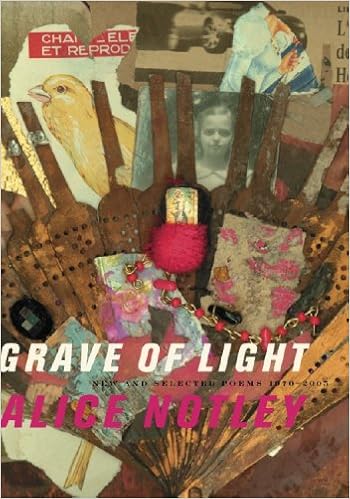

That, oddly, is the name of a poem. One by Alice Notley, from her 2006 collection Grave of Light. I’ve not read the book, but “The Ten Best Issues of Comic Books” was featured at the Poetry Foundation website, with a 44 second recording by the author. It’s as brief as it is improbable, just a list of titles and issue numbers, no explanations:

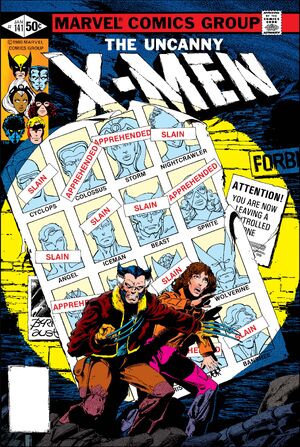

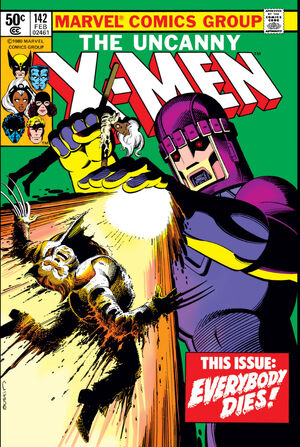

1. X-Men #141 & 142

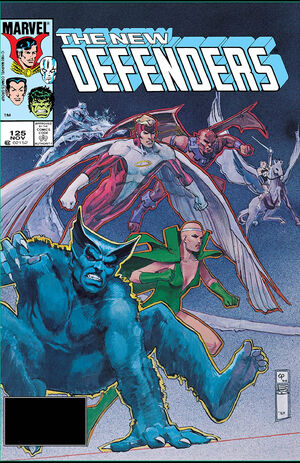

2. Defenders #125

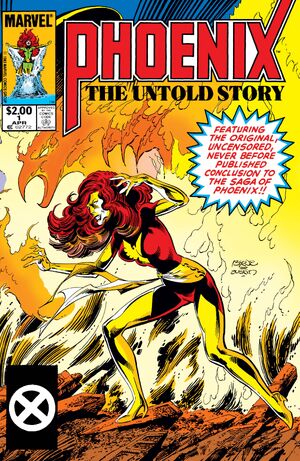

3. Phoenix: The Untold Story

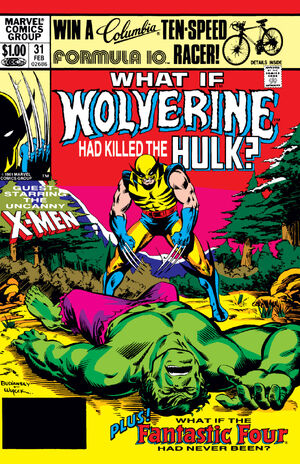

4. What if. . .? #31

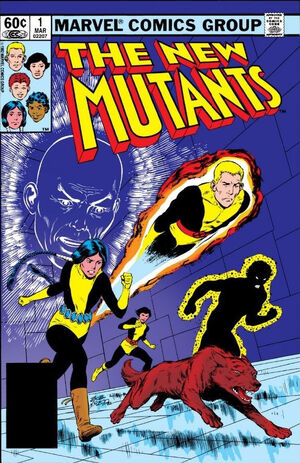

5. New Mutants #1

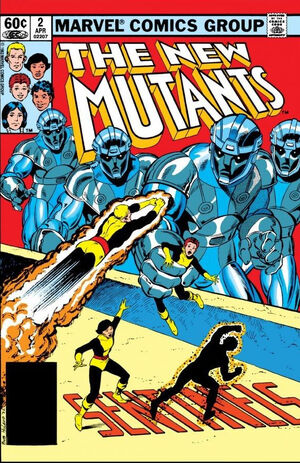

6. New Mutants #2

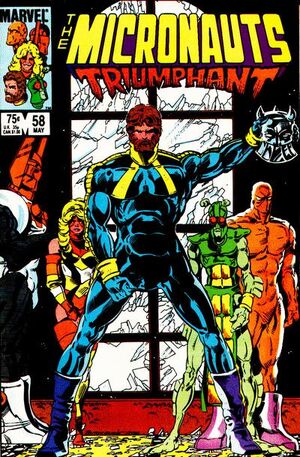

7. Micronauts #58

8. Marvel Universe #5

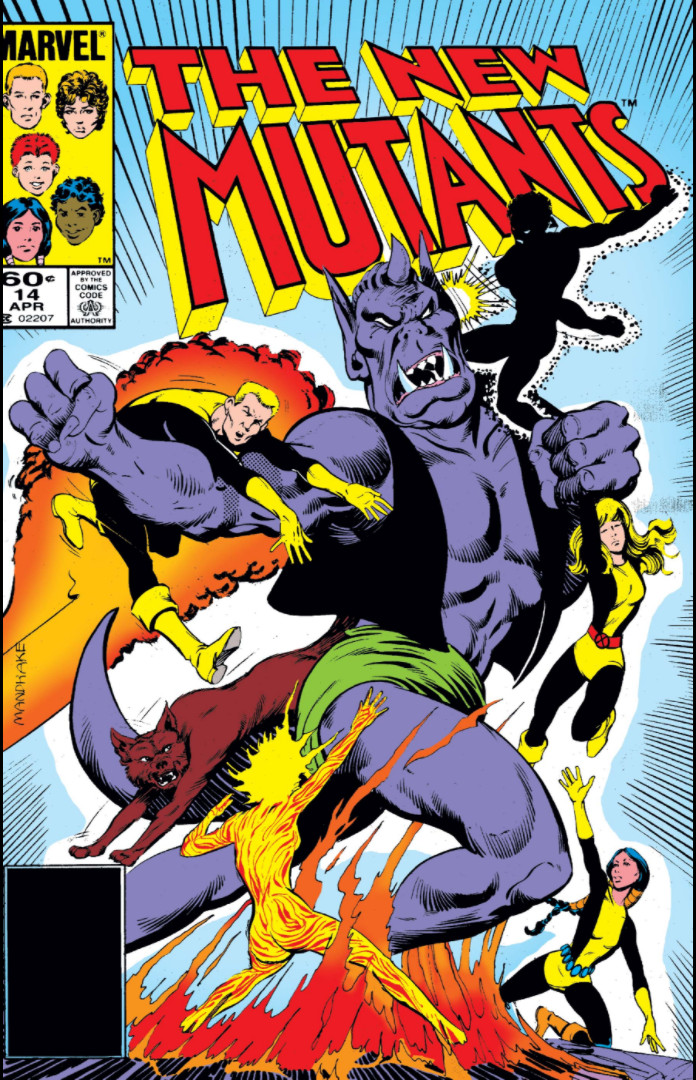

9. New Mutants #14

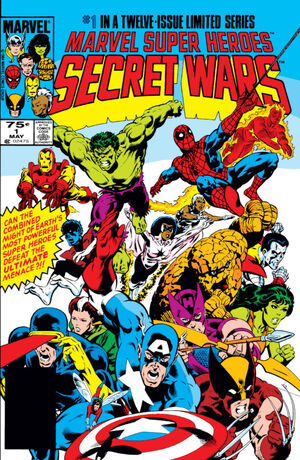

10. Secret Wars #1

I could debate the poem’s relative literary worth (moderate), or whether it should be considered a poem at all (most definitely), but I’d rather explicate the list itself, starting with dates and covers:

1. January & February 1981:

2. November 1983:

3. April 1984:

4. February 1982:

5. March 1983:

6. April 1983:

7. May 1984:

8. The 2009 publication date confused me, until I realized the content begins in 1982 for Iron Man, 1981 for Spider-Man, and 1987 for X-Men:

9. April 1984:

10. May 1984:

First thing you should notice: Ms. Notley and I went to high school together. How else to explain our nearly identical, late adolescent reading list? I attended high school from 1981 to 1984, the exact years covered by the list. And yet if you google Notley, you’ll see she was not born in 1966 like me, but 1945, putting her at 39 the year I graduated.

So, if we read the list as autobiography, why was the poet reading so much Marvel in her late thirties? And not just Marvel, but specifically X-Men. Nine of the ten issues feature team members. Six are written or co-written by Chris Claremont, the longest running writer for not just the X-Men, but for any comic book series ever. Even the New Defenders include three Old X-Men–plus one of Bill Sienkiewicz’s earliest painted covers. I would have thought that at least one of the three New Mutants would have featured Sienkiewicz too, but they’re all before he began drawing the series. Notley also departs twice from official Marvel continuity with an alternate version of Wolverine’s debut and Claremont and Byrne’s alternate version of the Dark Phoenix Saga in which Jean Gray survives. Secret Wars, by the way, is by far the worst comic on the list–and I say that having not read Micronauts, the true outlier here. I remember my brother had an issue or two of the series, tie-ins to the toy franchise. Sadly, marvel.wikia.com has no synopsis, but no X-Men are included on issue #58’s character list.

So what to make of this poem? It’s an aggressively obscure ode to the mostly early 80s X-Men, with a couple of turns inexplicable to even this professorial fanboy who was right there at the time. Though only an obsessive googler would know even that much. Is Notley a supervillain sending me on a diabolical mission to nowhere? On its surface, the poem is just that, its surface. An impenetrable list of references. No content, personal or otherwise. Its title suggests objectivity–favorite lists usually do–but the list itself is exceptionally subjective, the top ten of a very specific person who would have read comics at a very specific moment with a very specific reading bias. Yet the speaker (and I don’t think it’s an autobiographical version of Notley after all) gives us no hints about her criteria–and therefore no hints about herself either. We only get her pop culture skeleton. She remains invisible.

Or maybe intangible–like Kitty Pryde on that line-one cover of “Days of Future Past.” Apparently some timelines really can’t be saved.

Tags: Alice Notley

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

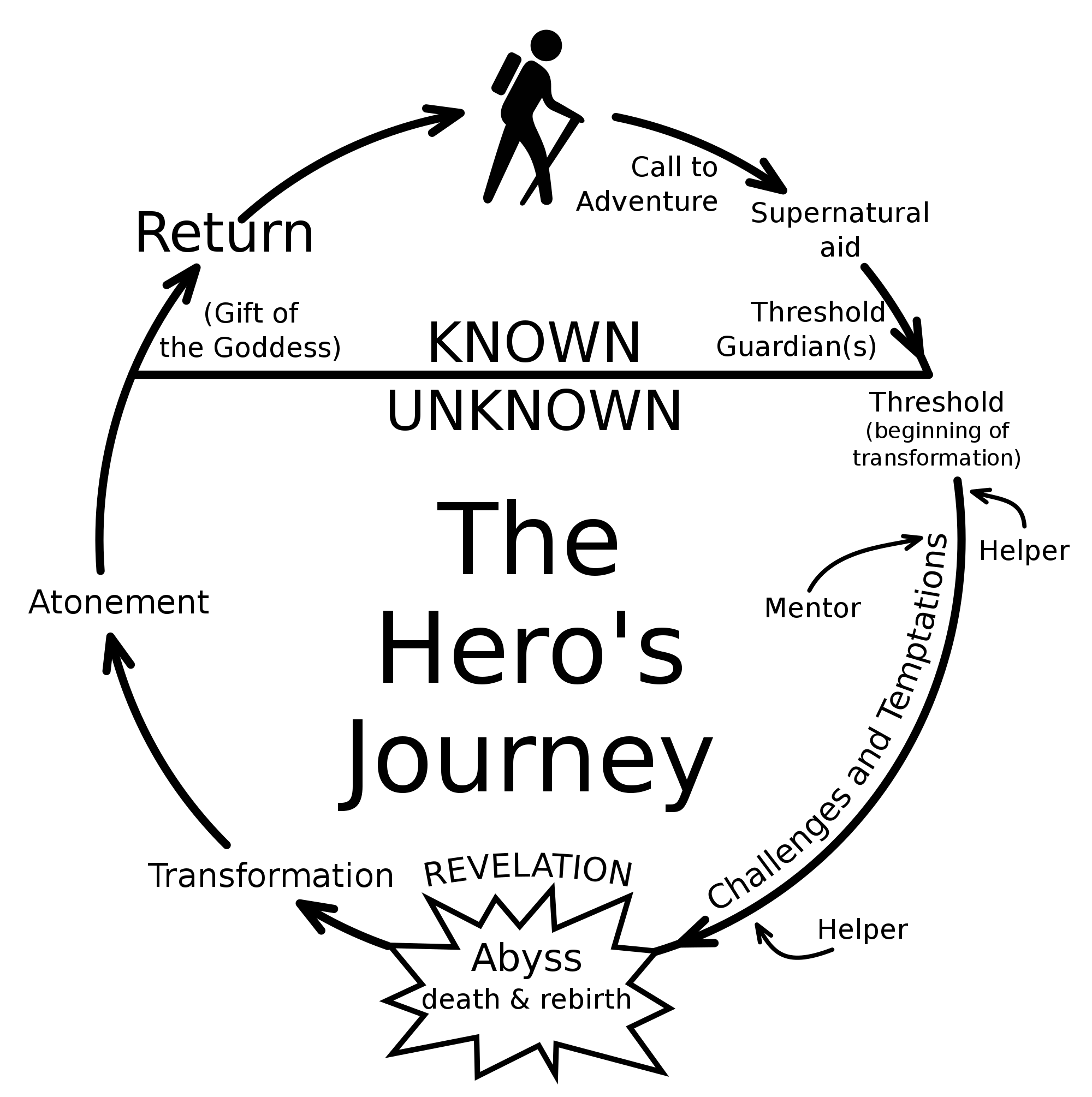

05/09/16 The Superhero Monomyth?

When Hollywood executive Christopher Vogler summarized Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces as a guide for screenwriters in 1985, he called it “one of the most influential books of the 20th century,” noting that “The myth can be used to tell the simplest comic book story or the most sophisticated drama.” Campbell’s book introduced his concept of the monomyth, an 18-step narrative formula he applied across societies and time periods world-wide. His examples include Greek, Roman, Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Norse, and Inuit sources. Campbell did not, however, relate his analysis to the hero type most popular while he was developing his formula in the 40s: the American comic book superhero.

Campbell published his study shortly after DC terminated Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, ending their ten-year contract on Action Comics. Superman, meanwhile, had expanded to newspapers, radio, film, and TV, producing a legion of similarly superhuman imitations. While Campbell’s approach to comparative mythology is flawed by inattention to differences between disparate tales and cultures, it shares its mid-century, American context with the superhero genre and so suggests one culturally-specific explanation for the character type’s popularity. What appealed to Campbell appealed to other 20th century U.S. readers too.

Campbell summarized his monomyth’s essential elements:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

The description encapsulates superhero origin stories. Will Eisner condensed the same elements into the first panel of Wonder Comics #1 (May 1939), when a blond-haired American vacationing in Asia receives supernatural powers from a turbaned Tibetan:

“So, Fred Carson, wear this ring as a symbol of the Herculean powers with which you are endowed—as long as you wear it, you will be the strongest human on Earth—you will be impervious—and now in the name of humanity and justice, go forth into the world!”

Wonderman premiered the same month as Action Comics #12 and Detective Comics #27, which introduced Bob Kane and Bill Finger’s “Bat-Man.” Both characters were the first direct imitations of Siegel and Shuster’s industry-transforming Superman. While Superman was influenced by decades of pulp, film, and penny dreadful predecessors, the medium-specific tradition of the comic book superhero begins in 1939 with the expansion of a single character into a repeated character type.

Like Wonderman’s, Batman’s origin story, retroactively inserted six months later in Detective Comics #33, is a monomyth variant—though a darker one. Bruce and his parents are “walking home from a movie” when they encounter the dark forces of the criminal underworld. After the “terror and shock” of the murders, a “curious and strange scene takes place,” in which Bruce vows to his parents’ spirits to avenge their deaths and so becomes “a creature of the night” himself. Finger places the formative event in an inexact past, “some twelve years ago,” suggesting the ahistoricity of many myths and folktales, while also grounding the ongoing consequences in a contemporary moment. The formula suggests comparative religion scholar Mircea Eliade’s analysis of a past mythic time and the ability of followers to return to it through ritual imitation. Superheroes pass between Campbell’s “two worlds, the divine and the human” regularly.

The relation of an origin to contemporary adventures is also central to the monomyth as embodied by superheroes. While Krypton is the original comic book region of supernatural wonder, giving Superman the power to bestow boons on humanity, Clark Kent is the ongoing embodiment of the world of the common day. Structurally the Krypton past is only preamble, establishing one of the most significant elements of Campbell’s heroic journey: personal transformation.

Myths and folktales are complete stories that end in closure, but superhero comics are typically episodic and endlessly incomplete. The monomyth as applied to comics form then is not limited to a character’s origin nor necessarily expandable to an accumulative series. The superhero monomyth is a single adventure—and, in fact, each and every adventure. The early twelve-page Action Comics episodes begin with Clark, who abandons his common day persona to encounter some fabulous force which he decisively defeats, before returning to live among humans as Clark again, his boon-bestowing powers at the ready.

If Campbell is correct, and the appeal of the myths he studied is grounded in the cyclic pattern of common heroes transforming through a descent into the fantastical, superhero comics enacted that script monthly. Every time Bill Parker and C.C. Beck’s little Billy Baston accepts a call to action and shouts “Shazam!” he receives the aid of his wizard mentor and crosses a supernatural threshold, causing Billy to vanishes and be reborn as Captain Marvel. Campbell writes:

“The hero, instead of conquering or conciliating the power of the threshold, is swallowed into the unknown and would appear to have died. … This popular motif gives emphasis to the lesson that the passage of the threshold is a form of self-annihilation … instead of passing outward, beyond the confines of the visible world, the hero goes inward, to be born again.”

After the trials of physical combat end in victory, Captain Marvel returns to the mundane world by transforming back into Billy Baston. Campbell describes the act as a trial itself:

“The first problem of the returning hero is to accept as real, after an experience of the soul-satisfying vision of fulfillment, the passing joys and sorrows, banalities and noisy obscenities of life. Why re-enter such a world? Why attempt to make plausible, or even interesting, to men and women consumed with passion, the experience of transcendental bliss? As dreams that were momentous by night may seem simply silly in the light of day, so the poet and the prophet can discover themselves playing the idiot before a jury of sober eyes.”

Siegel and Shuster solved Campbell’s dilemma by presenting Clark Kent as the hero’s banal disguise, allowing him to play an idiot to Lois Lane and the mundane temptations she represents. As Jules Feiffer concludes, Clark “is Superman’s opinion of the rest of us, a pointed caricature of what we … were really like.” Superman’s adoption of the caricature also reflects Campbell’s final monomythic stages, allowing him to remain in the never-ending moment by mastering both of his worlds:

“Freedom to pass back and forth across the world division, from the perspective of the apparitions of time to that of the causal deep and back—not contaminating the principles of the one with those of the other, yet permitting the mind to know the one by virtue of the other—is the talent of the master.”

Viewed within the monomythic scope of each episode, the Clark of the opening scene is fundamentally different from the Clark of the ending scene. If a reader had never heard of Superman, she would see a human transform into super-being and then relinquish that soul-satisfying fulfilment in order to appear human again. Other superheroes enact the same cyclic transformations every time they don a costume. Though Campbell’s monomyth can be applied only tentatively to the diverse array of world mythologies, it may find its most defining embodiment in the comics produced at its same cultural moment.

Tags: Batman, Captain Marvel, Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell, Monomyth, Superman, Wonderman

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized