Monthly Archives: April 2018

30/04/18 Occam’s Closure

Don’t add stuff you don’t need. That’s not quite the definition of “Occam’s Razor,” but it’s close. The 14th-century Franciscan friar prefered the simplest answer, the one that requires the fewest assumptions, the straightest line between two points of thought.

Last week I suggested an alternative to Neil Cohn’s narrative grammar for analyzing comics, one that harmonized both Freytag’s plot pyramid and Todorov’s equilibrium circle:

And though I prefer my terms and visuals over theirs, Occam is asking me: does this approach add anything? My panels and Cohn’s panels mostly overlap:

In this Peanuts examples, I was surprised to see Cohn categorizing the third panel as an “Establisher” (“sets up an interaction without acting upon it”), a narrative position that aligns with my balance panel. But rather than revealing a difference in our approaches, I think Cohn is just off within his own system in this one case. I think that’s actually an “Initial” (“initiates the tension of the narrative arc”), and the fourth panel is instead a “Prolongation” (“marks a medial state”). If Snoopy wasn’t already running toward the ball in panel three, then I would agree with “Establisher,” but I’d say they’re already interacting.

So while I still prefer my terms, definitions, and visuals, but do they merely clarify? Cohn’s system names panels that are present. Mine provides a way of identifying the narrative elements that aren’t drawn. They make visible what’s not there, the inferences between the images. Scott McCloud called that “closure,” an imperfect term for reasons I won’t go into here, but I don’t blame Neil Cohn for avoiding it. But he avoids the concept too, attending only to the narrative elements that appear as panel content. So to understand what’s between those panels, I’m suggesting a different approach:

Like McCloud’s closure, Occam’s focuses attention on the inferences between images. What happens in the gutter? I’d say as a rule: as little as possible. But how does a reader know what that is? What are the organizing constraints on closure? Look at the first juxtaposition:

The possibilities are oddly infinite. Charlie Brown wound up–but then maybe relaxed, adjusted his grip, stretched his arm, kicked the ground a couple times, adjusted his cap, wound up again–and then began to throw. Maybe the next panel is a week later, after he’s been dropping snowballs with each attempt but practicing again and again until finally he throws one. Neither of those possibilities seem likely. But why not? Because of Occam’s rule of closure:

The undrawn story content between representational images is only the minimum required to satisfy missing plot points.

The shortest path between the plots points disruption and climax is imbalance, the halfway point between the wind-up that ends the implied state of balance and the ball release that restores balance by ending the throw.

What about the rest of the Peanuts strip?

Assuming every plot has to either depict or imply all five points, then we have to infer that Charlie Brown is in a state of balance both before and after throwing the ball, and that Snoopy is in a state of balance before running after the ball. That means Snoopy’s plot leaves less to infer–unless you break it into smaller units of action.

In panel four, Snoopy is facing the oncoming ball. In the next, he is facing away from it and running, and the snowball is larger. What is the shortest path of inferences between those two points? Snoopy turned and began to run, and the ball grew in size as is it continued to roll. That describes a midpoint for both actions, and so imbalance: Less seems to happen in the preceding juxtaposition between panels three and four. The ball must have begun to roll, and Snoopy must have slowed but not yet fully stopped:

Less seems to happen in the preceding juxtaposition between panels three and four. The ball must have begun to roll, and Snoopy must have slowed but not yet fully stopped:

Looking again, I notice that the ball has increased in size too. So it goes from small and stationary to larger and moving toward Snoopy, and Snoopy goes from moving toward it to stopped. The two images require an explanation for those changes: we assume that gravity started the ball rolling and that Snoopy stopped himself because he saw it moving toward him. We assume nothing else because nothing else is required. Occam’s rule of closure is a reader’s default setting for understanding juxtaposed images.

Looking again, I notice that the ball has increased in size too. So it goes from small and stationary to larger and moving toward Snoopy, and Snoopy goes from moving toward it to stopped. The two images require an explanation for those changes: we assume that gravity started the ball rolling and that Snoopy stopped himself because he saw it moving toward him. We assume nothing else because nothing else is required. Occam’s rule of closure is a reader’s default setting for understanding juxtaposed images.

The last combination implies more. I see at least four required plot points:

First consider the plot of the snowball. It begins in panel three in a stated of literal balance. In panel four it begins to roll and grow, a disruption of its balance. In panel five, it continues to roll and grow, so a continuation of its imbalance. At some point we assume it stopped growing and rolling. We don’t know the exact circumstances of that climax, but the images require us to make that minimum assumption. And once stopped, we also assume it remains stopped, that the snow that comprised the ball is again in literal balance again.

Removing Snoopy from the drawn panels makes this more obvious:

Assuming a naturalistic world, we also have to understand the image of Snoopy hiding behind the tree to imply that the tree was previously standing by itself, and so in balance. Snoopy must have approached it, disrupting its isolation, and then arrived behind it before looking out:

There’s a good reason why Shultz didn’t draw those three extra panels. They’re boring. It’s far more fun to experience the plot points through the assumptions implied by the final, balanced panel–one that encapsulates through closure an entire action sequence or subplot while also curtailing unrequired inferences.

There’s a good reason why Shultz didn’t draw those three extra panels. They’re boring. It’s far more fun to experience the plot points through the assumptions implied by the final, balanced panel–one that encapsulates through closure an entire action sequence or subplot while also curtailing unrequired inferences.

Occam’s closure explains that.

[If you’re interested, this is part of a four-part sequence. It begins here and continues right here and then here and ends here.]

Tags: comics theory, Neil Cohn, plot

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

16/04/18 April Woods

I didn’t know Thomas Joyner. I adore his mother but only know her because my children took Latin in middle school. They’re both rising seniors now, one in high school, one in college, so we haven’t exchanged more than a passing nod in years. My kids also took Latin in high school from Pat Bradley, who lives three doors down from the Joyners. Pat wrote a letter to Laura the day after Thomas died, and she asked him to read it at Thomas’ memorial on Saturday. It is one of the best pieces of writing I’ve ever heard. I was standing along the back wall of the church balcony with my son and wife, unable to see Pat at the microphone below, but feeling my throat thicken and shake with his.

I have no right to the surges of emotion I’ve been choking back all week. My wife says I literally run from the room when the topic of Thomas comes up. It feels like a selfish pain, because it’s less about Thomas than imagining myself as Laura, imagining the impossible loss of my own children and what would follow it.

When my mother died in January, I found myself creating images instead of writing. When I got up the Saturday morning of the memorial, I started drawing trees. Lesley and I have begun a collaborative project of image-texts, or poetry comics: her words, my Word Paint. I ask for assignments, images, ideas that she then responds to, and so she had texted me a photo of a blooming tree she’d taken on her phone. I wasn’t thinking about Thomas. I was just drawing lines. One black mark at a time, then doubling them, layering them deeper, before finally inventing April buds:

Really I should have stopped there. That was my image for Lesley, my lob back to her in our game of image-text badminton. But the pre-bud version of the tree stuck with me, and I found myself hunched at my laptop again, clicking in layers and layers of black branches, before framing them, doubling them into a dark woods:

When I emailed that image to Lesley’s computer upstairs, she wrote back a poem about loss, about fear, about the inability to protect. Somehow I didn’t realize this was all about Thomas until changing for the memorial. The invitation said Hawaiian shirts were especially welcome, but I had to settle for a purple polo. Apparently those woods needed some purple too. I kept clicking until it was time to leave, and then kept clicking when we got back.

I’m the first to acknowledge that I’m no artist, and my PC is a paltry canvas. I don’t have words for Thomas either. We were strangers, but our lives interwove, every branch touching a dozen others, every sympathetic twitch quivering through the canopy.

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

09/04/18 “Blurgits” (or “She threw her arms in the air”)

From Mort Walker’s The Lexicon of Comicana (1980): “Blurgits are produced by a kind of stroboscopic technique to show movement within a single panel, or to produce the ultimate in speed and action.”

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

02/04/18 My Favorite Sex Fantasy

Sophia Foster-Dimino is an excellent cartoonist. So was Pablo Picasso. The difference is that no one ever calls Picasso a “cartoonist” because it sounds like an insult or a damningly faint, left-handed compliment. But in Foster-Dimino’s case I mean it as loud ambidextrous praise. She, like Picasso, understands and exploits the complexities of simplified distortion. Her ten-story collection Sex Fantasy is drawn in a consistent and deceptively simple style of clean black lines, occasional black shapes, and no grays or cross-hatched shading. Though the images suggest a world of equally simple experiences expressible through faces capable of only the most basic expressions, her subject matter and ultimately her technique are far more complicated.

Her first chapter includes Sex Fantasies 1-3, often surreal litanies of various first-person narrators carrying out or expressing variously mundane or impossible acts and feelings. The next chapter switches to narrative form, but with an accompanying increase in ambiguity. Is the figure whispering hurtful remarks into the main character’s ear only her self-destructive inner voice? Are the two women meeting for lunch actually aliens passing for humans? And if so, why does the picture on the wall keep changing expressions? Later fantasies vacillate between naturalism and the surreal. A horrible husband turns out to be only a horrible communicator. An inexplicably doll-sized woman unites with her inexplicably doll-sized boyfriend. The final, lone, and longest story is also the most realistic, with its two characters debating whether to have an affair despite his being married to her close friend, but the grocery store scene of a sex game devolving into infantilizing torment is perhaps the most disturbing. All are rendered in Foster-Dimino’s minimalistic cartoon style.

But what is a cartoon?

Pioneering comics scholar Scott McCloud describes cartooning as “amplification through simplification.” He writes: “When we abstract an image through cartooning, we’re not so much eliminating details as we are focusing on specific details,” creating a visual style that has a “stripped-down intensity.” McCloud illustrates his point with a series of faces beginning with a photograph and ending with an oval containing two dots and a line, which he calls a “cartoon” because it is the most “simplified.” But this is only half true. While the cartoon face is the simplest in terms of detail—it has the fewest number of lines—its lines also differ from the lines in the other faces in terms of shape: the cartoon lines are more exaggerated. They don’t match the shapes of the photograph, and so their intensity isn’t just “stripped-down.” It’s also warped.

A cartoon typically does both: simplify and exaggerate. That combination creates a story world very different from our world, a fantasy universe that allows for a range of impossibilities, from South Park anatomy to Road Runner physics. That’s why comics scholar Joseph Witek coined the term “cartoon ethos”:

“by stripping away the inessential elements of a human face and exaggerating its defining features, caricature purports to reveal an essential truth about its subject that lies hidden beneath the world of appearances. When structuring caricatures in sequence, the cartoon mode treats the comic’s page not only as a loose representation of physical existence, but also as a textual field for the immediate enactment of overtly symbolic meaning.”

But sometimes we, like McCloud, think of simplified but otherwise roughly realistic images as “cartoons” too. What sort of hidden truths and symbolic meanings do they reveal? Foster-Dimino takes brilliant advantage of that in-between ambiguity.

Her “Sex Fantasy 5” depicts a couple hiking together as they reveal stories about their pasts. Neither character initially has a name, and both are composed of a minimum of lines that simplify features to circular eyes and mouths and leave skin and fabric untextured by shade and depth. The first figure Foster-Dimino draws with short black hair and thick black eyebrows, wearing shorts and a sweatshirt. The second she draws with light hair tied in a ponytail and thin eyebrows, wearing a tank top, leggings, and a fanny pack. I registered the first as male and the second as female—probably because, as McCloud says, those few specific details are often-used markers of gender in the stripped-down reality of contemporary cartooning.

So is height. But even though the longer-haired blonde appears a few inches taller than the shorter-haired brunette, “she” was still female in my mind. Though the gender markers fluctuate in flashbacks, my initial assumptions filled in missing details—both visually and narratively—so both figures maintained their gender identities without corroborating visual evidence and even despite some apparent contradictions. When “he” describes his childhood, “he” sometimes has the same short black hair, but other times it’s longer and ponytailed. “She” says: “when I was young I looked very different from how I am now. It took me a long time to settle on this look.” The array of accompanying images demonstrates that range, each version appearing variously female or male—but despite that intentional visual ambiguity, I understood each to represent a biologically female body.

The punchline of course is that “she” is male and “he” is female, as Foster-Dimino reveals in the collection’s single, albeit mild sex scene in which “he” removes his shirt and then bra to expose breasts and “she” removes her tank top to reveal none. Did Foster-Dimino mislead us? Certainly. But look back at the previous pages and see that we also fooled ourselves, since the implied bagginess of “his” sweatshirt would easily obscure breasts, and “her” more tightly fitting tank top clearly covers no breasts at all.

So how can such “essential elements” of gender go unnoticed? Foster-Domino was cartooning in the simplifying but not exaggerating sense. Rather than assuming her characters existed in an impossible world of cartoon proportions typical of, say, Charlie Brown or Beetle Bailey, we understand them to be inhabitants of either our world or a realistic world very much like it. So instead of reading the lack of detail as a photo-like representation of that world, we understand it to be merely artistic style. The actual characters—who do not exist on the page but in our heads—are as detailed as anyone in our world. And yet those details exist only in our detail-providing imaginations, a fact Foster-Dimino knows and happily exploits. By stripping her characters down to stereotypical elements, she knows we will fill-in the corresponding but ultimate wrong set of gender details.

But that’s not her final punchline. Foster-Dimino takes “Sex Fantasy 5” one cartooning step further with a second reveal that returns the story world to Witek’s cartoon ethos, where stories:

“often assume a fundamentally unstable and infinitely mutable physical reality, where characters and even objects can move and be transformed according to an associative or emotive logic rather than the laws of physics. Bodies can change suddenly and temporarily in shape and proportion to depict emotional states or narrative circumstances, as when the body of an outraged character swells to many times its normal size, or appears to levitate several feet off the ground in a cloud of dust.”

Rather than levitating, the character formerly understood to be female swells into an enormous comet-shaped creature composed entirely of wings and suggestive of no sexual identity. The character formerly understood to be male watches nonchalantly before “she” grabs onto to “his” back as they fly away, saying: “I didn’t know you could do that.”

We didn’t know either—a fact far more biologically significant than “his” or “her” breasts. Does this winged being also have a penis or a vagina? At differing points during my first reading, I would have answered yes separately to both. Now, I’m not so sure. Which is Foster-Dimino’s point—one expressible only through the point of her deceptively simplifying cartooning pen.

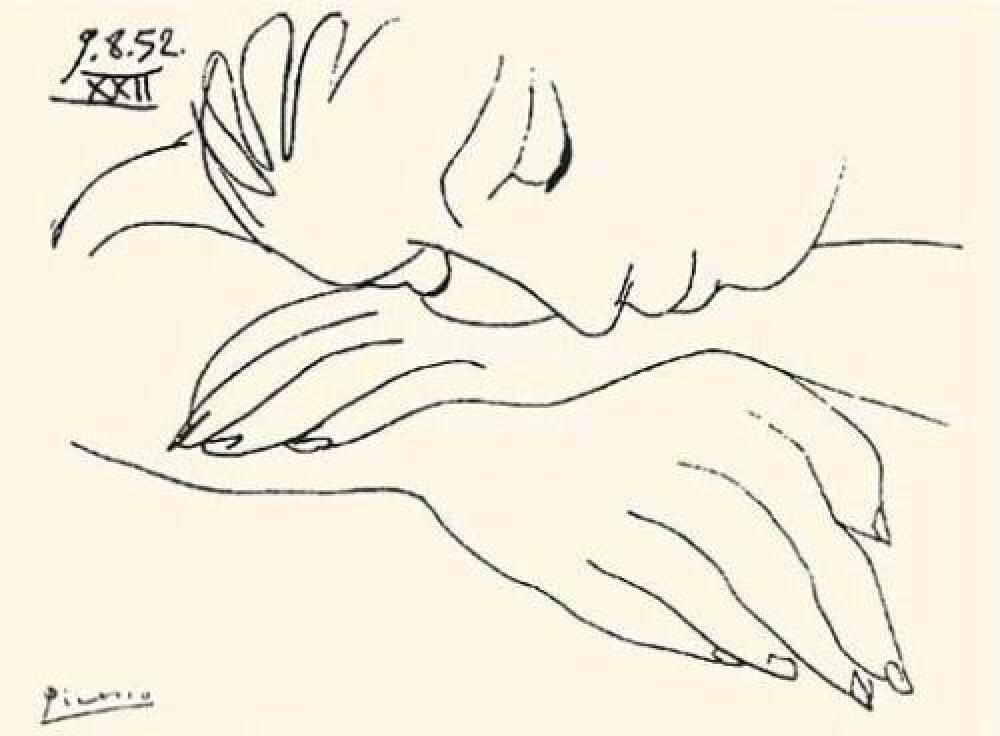

[Check out more of Foster-Dimino’s work at her website. A version of this post and my other recent comics reviews appear in the comics section of PopMatters. Oh, and here are some Picasso “cartoons”:

Tags: Sex Fantasy, Sophia Foster-Dimino

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized