Monthly Archives: August 2019

22/08/19 Fishing for Talking Babies in a Pencil Gray Sea

As much as I enjoy U.S. and U.K. comics, some of the best English-language work is coming out of other countries right now. Certainly Drawn & Quarterly and Koyama Press have proven Canada’s oversized presence, and though Fantagraphics Books is stationed in Seattle (which is sort of Canada?), some of their most exciting releases feature international authors. Earlier this year they debuted Danish artist Rikke Villadsen’s first English-language comic, The Sea.

Though I would be content to read a translation of a work previously published in Denmark, The Sea is significantly more than that. Many comics develop their text and images independently, with artists leaving talk bubbles and caption boxes empty for letterers to fill with mechanical fonts digitally. While this is a reasonable division of production labor, one that also allows for textual revision until pages head for the printer, it can create a visual discord between the pleasant imperfections of hand-drawn artwork and the rigid reproduction of identical letters in identically spaced rows. Too often comics creators ignore the visual fact that words are images too.

Not Villadsen. All of her words are hand-drawn in an idiosyncratic style, merging script and font and bold flourishes in curving rows that echo the shapes of the talk bubbles that contain them. Translating The Sea into another language would require not simply rewriting text, but redrawing it and so altering all of her original artboards. While a loss for non-English readers, the result is a comic that fully exploits the visual potential of its text. Because Villadsen uses no exterior narration, all of those hand-drawn words also evoke the spoken sound of the characters who voice them, further deepening their visual characterization.

Villadsen’s words, like the rest of the art they appear in, are drawn with pencils. Comics artists typically produce penciled sketches which they or collaborating artists ink over to create line art that is then colored or printed in black and white. For Villadsen, penciling is not a step in a production process. The penciled pages are her finished product. The Sea consists entirely of pencil marks, from delicate crosshatching to rulered frame lines to the smudged smears presumably produced by Villadsen’s own thumb on the original art. While colorless comics are common, it is rare to find the kinds of gray gradations of The Sea—a style ideal for Villadsen’s subject matter, since her main character is lost in the gray waters and gray fog of the North Sea. Though he partially escapes the monotony through what may (or may not?) be surreal fantasies, even the fisherman’s imagination remains caught in the monotone pencils that literary shape him and his world.

The imprisoned effect is heightened by the full-page bleeds and the absence of a formal gutter. Villadsen always draw to the page edge (and so necessarily beyond it on her artboards), and rather than framing each panel individually to produce an undrawn negative space between them, her panels share single frame lines. Because the panels are gridded—usually 2×2, with occasional 3×2 and other variants—the combined effects produce a net pattern continuing across pages, as if the story is caught in the same trap that the fisherman pulls from the sea.

Villadsen also draws her main character and his surroundings in a style that at first glance feels cartoonish, because his features are exaggerated and distorted, sometimes as if by the hand of a child, though there is nothing untrained about Villadsen’s artistic choices. But cartoons are also typically simplified too, with only a minimum number of lines needed to define their most essential shapes. Villadsen instead crosshatches her world with a naturalistic level of detail, producing a visual surrealness that matches her story content when her sailor nets a talking fish and a talking baby.

The graphic novel leaves its watery setting for the first time when the baby begins to recount in image-only narration the circumstances of how he (or she—Villadsen always poses a bare leg in front of its genitals) ended up in the sea. We spend the next sixteen pages on the shore where the child’s mother, after scooping up water and boiling it and pouring it back blacker into the sea, removes her Puritan-modest dress and has intercourse with a lighthouse. Villadsen parallels the change in story topic and tone with a striking change in visual style, penciling the mother in naturalistic proportions nothing like the sailor’s distorted features but everything like a pornographic supermodel’s.

If the sane nineteen-image sequence were drawn by a male artist, I might lose trust in the project overall. But Villadsen knows what she’s doing. Earlier in the novel, the fisherman breaks the page’s fourth wall to address the reader and display his tattoos. They include a sailor meeting a prostitute, four female nudes, a fully-dressed nurse, and a sailor before a tomb marked “In Memory of Mom.” These drawings of skin-deep drawings, what that fisherman appropriately calls “painful doodles,” seem to encompass the world of tiny possibilities that he is able to picture for women. Though the sea is vast, his world, like his imagination, is hopelessly limited, as he sails alone on his small boat through identical gray waves.

It is no surprise that he refuses to take responsibility for catching the talking fish and baby, instead blaming them for swimming into his net. When they critique his language as insufficiently old-fashioned, he refuses to change, preferring “fuck” to “hornswoggle” or “grumbleguts.” According to his tattoos, he also prefers “fuck” to “True Love.” A tale of his own origins follows with his unknown, kelp-smelling father and his shrimp-peeling mother whose breasts creak like tree trunks in a storm.

Though already thoroughly surreal, the novel grows even stranger as each growing wave threatens to capsize the tiny ship. Ultimately, Villadsen appears to be spinning a circular tale-within-a-tale with no origin or end point and only tragic escapes. What it all means in terms of narrative and the implied gender critique grows as murky as the thumb-smeared fog, but the trip itself is worth the cost of any cruise on Villadsen’s idiosyncratic sea.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Rikke Villadsen, The Sea

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

19/08/19 Graphic Sex

First, an anatomy lesson: the perineum is the area between the anus and the vulva or scrotum. The adjective form is “perineal,” as in: “Midwives use different perineal techniques to allow the perineum to stretch during childbirth and prevent injury.” The Perineum Technique is something quite different. Its cover (which could be an outtake from the orgy scene in Stanley Kubrick’s unfortunate final film, Eyes Wide Shut) include not only its two, masked, sword-wielding protagonists, but also a masked and almost fully nude woman strolling through the chandelier-decorated background. Masked nudity is an oxymoron, one at the heart of this gratuitously prurient yet subtly insightful study of the graphic novel form.

Subtle and gratuitous—that’s another oxymoronic combination. Ruppert and Mulot thrive on them, combining discordant elements designed to both confuse and titillate. In the opening eight-page sequence, a man and woman climb a ladder positioned perilously close to the edge of an impossibly high, thin monolith, tip it and themselves over, and while in free fall, strip their clothes, plunge their swords into the side of the monolith to slow their descent, and simultaneously have intercourse, before vanishing below the continuing panels which soon frame only the wavy lines of their lingering sword marks. Those markings resemble the loose edges of the panel frames, forming shapes that could be interpreted as either phallic or yonic or both.

But that’s not the confusing part. While performing all of these actions, the two talk in a matter-of-fact tone, discussing what sex fantasy she will visualize in order to orgasm while acknowledging that the details are too personal for her to tell him. The punchline hits at the bottom of the last column when the man is revealed to be reclining on his couch, with his pants at his ankles and his laptop on his thighs. They’re having Skype sex.

It’s an interesting set-up, but while the reveal instantly resolves the tonal tension of the dialogue, it increases the visual complexity since there are now at least three layers: what each sees through their webcams (“You’re kind of backlit, but if you shift a bit to the right …”), what she mentally visualizes (“It’s a scene that takes place in the bathroom of my old apartment”), and the now yet-more-ambiguous panel images. The monolith is the same pink-orange as his legs, suggesting a dream-like relationship to the real world, but it must also be somehow actually real since they discuss the swords directly (“Can we trade weapons? Just this once?”).

When the scene is interrupted by the man’s work assistant dropping by his apartment to pick up a video, the tonal oddity returns in the unexpected frankness of their conversation. When she asks him if he was in the middle of something, he tells her. “That’s cool. How’s it work? With Skype, I mean.” “We talk and then we touch ourselves in front of the webcam. Here’s the hard drive. The finger video’s on it.” There’s no hedging, no embarrassment, and no arousal either. The assistant isn’t titillated, just curious in the way she might be if her boss had adopted a pet or bought an appliance she’d never used before.

While the sexual matter-of-factness isn’t exactly other-worldly, the effect is. The world of The Perineum Technique is sort of our own world, and sort of not. It’s an area between. In comics, the most significant “area between” is the gutter, the usually ignored space between panels—what in this analogy would be the genitals, what you pay the most attention to. Like an actual perineum, the gutter stretches, shrinks, bends, does whatever is required of it to allow the presentation of images in the page layout. The larger story world of the novel does something similar, obeying psychological laws of not-quite-realism in order to play its games.

JH and Sarah, the Skype partners, soon complete their tryst, establishing the novel’s core plot point: he wants a relationship, she wants sex with a stranger. It’s a familiar set-up, a variation on Marlon Brando and Marie Schneider in Bernardo Bertolucci ‘s Last Tango in Paris (1973). Did I mention Ruppert and Mulot are French? La technique du périnée, the authors’ fourth collaboration, was originally published in 2014 and is better called a bandes dessinées (drawn strips), the term for French and Belgium comics. That difference in traditions accounts for some but not nearly all of the graphic novel’s peculiarities.

The metafictional games intensify. JH is a famous video artist, and the opening visuals are actually his vision for his next project, which expands to include more self-referential image-within-images of his obsessive attempts to connect with Sarah. They include hara-kiri and finger amputation, because for JH everything is a sexual metaphor. His “techniques” for wooing Sarah out for a drink culminate in their meeting for dinner at a so-called swingers club. When she makes him ejaculate under the dinner table (an image mercifully undrawn), the next panel frames the chandelier, an otherwise random setting detail that by juxtaposition evokes his orgasm. Afterwards Sarah explains the “perineum technique,” a tightening of the perineal muscles to prevent ejaculation, and tells him she’ll finally have dinner with him if he hasn’t ejaculated during the four months she’s gone.

I could go on, but the plot and characters all serve the novel’s relentless sexual drive. In the process, the authors continue to exploit the comics form for a range of impressive effects, all geared toward the plot goal of getting JH and Sarah in an actual bed, sleeping together literally rather than just figuratively. This means suffering with JH through a range of fantasies, including mentally stripping and redressing his assistant in a striptease burlesque costume and clutching a fire hose in front of eyeless and pornographically cartoonish dream women. While I admire the surreal frankness about sex, the actual surreal sex wears thin, especially when the story’s meta-guise thins to the point that the novel seems less about its characters and more about its implied male readers and overtly male authors. I have trouble imagining a female author making a book anything like this one—and that includes sexually exuberant artists like Julie Doucet, Fiona Smythe, or Julie Maroh—or a female reader finding the portrayal of Sarah (or of JH’s assistant, who, surprise surprise, does eventually end up in bed with him) convincing.

While the surface is about JH’s fantasies of Sarah, Sarah is herself already a fantasy, the idealized romantic object of Ruppert and Mulot’s collaborative id. For all its heterosexually fueled orgy energy, The Perineum Technique doesn’t really involve women, just their conceptual shadows in this for-boys by-boys masturbation romp. Fortunately, the novel does involve a great deal of ingenuity that pushes the comics form to new and tantalizing levels of invention. It just didn’t make me ejaculate, metaphorically or otherwise.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Florent Ruppert and Jerome Mulot, The Perineum Technique

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

12/08/19 Horns Make Every Thing Better

(My son is headed off to college soon, and I spent an obsessive amount of time this weekend making him a poster for his dorm wall. The phrase is his, and he applies it convincingly to a surprising range of songs. He used to play sax, before chess and number theory took over his brain. I’m going with the last version–which is also the last one I made. If your second child has an appreciation for horn sections and is starting college at the end of the month, feel free to make a copy too. It falls under the “empty nest” fair use clause in U.S. copyright law.)

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

05/08/19 Ash Can Cartoons

Three things I strongly suspect are true about graphic novelist James Sturm:

1) he is or has been married,

2) he has kids,

3) he doesn’t have a dog head.

Of the three, I’m least certain of the last. I also really really hope he didn’t vote for Jill Stein instead of Hillary Clinton in 2016, but honestly I have no idea.

The question is oddly central to Off Season, a graphic novel set in the aftermath of the presidential election, which both frames and represents the marital turmoil of the novel’s plot. From the opening panel of a turn-right traffic arrow painted on black asphalt below the caption-boxed chapter title “Stronger Together,” national politics infuse the story. Like the visual echo of the arrow embedded in the “H” of the Hillary yard sign seen in the next panel, the unglossed slogan references not only the failed Clinton campaign but also the narrator’s failing marriage, ironically encapsulating his own most salient feature: he needs his family to be together in order to be the strongest (or even a tolerable) version of himself.

The sixteen chapters range between three to fifteen two-panel pages, arranged left-to-right from an atypically short spine—the equivalent of “landscape” rather than “portrait” orientation. It may or may not be coincidental that Lynda Barry’s One Hundred Demons shares the same format since Barry’s memoir was originally published online as an episodic series at Slate in the late 90s, ending with the traumatic impact of Gore’s ambiguous loss to Bush in the wake of the Florida recount. Slate featured Sturm’s episodic chapters beginning in early October 2016—and so just before Clinton’s unexpected loss.

The seventh chapter (the sixth online) was published on the day of the election, the same day as within the story, too. For the book, the chapter title “Is It Really Over?” becomes the more definitive “It’s Not Over”—though the narrator’s stumbling marriage is identical. The ninth and final online installment is the most revised in book form, as the narrator’s breakdown peaks with his (undrawn) vandalism of a construction site after the repeatedly late check from his conman of a boss bounces, resulting in his daughter getting thrown out of her Judo class and an angry text from his not-quite-yet-ex-wife. It was a pretty bleak moment to end the original series, since the cop car in his rearview mirror is there to arrest him—except in the graphic novel, we learn later that he was only pulled over for texting while driving. While the new chapters are not as up-beat as the title of the next, “Working Through It,” might suggest, his personal campaign slogan “It’s Not Over” applies.

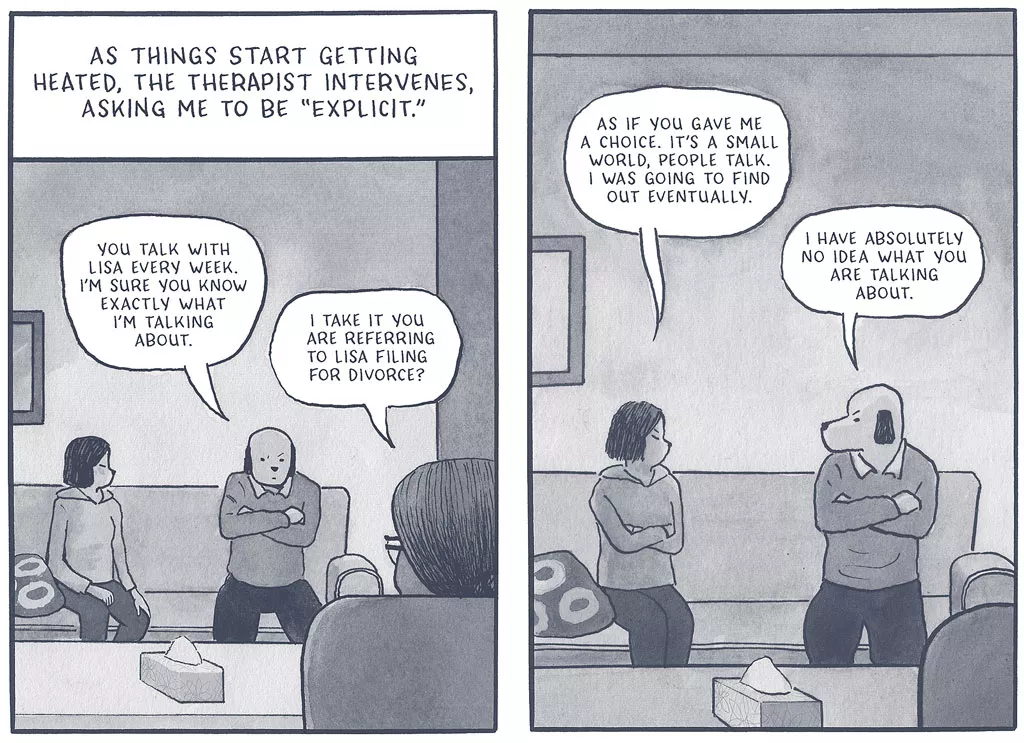

Sturm draws his story in a largely realistic style, with simple black lines filled with a gray-wash of details that give events a real-world solidity. Except for one intentionally glaring inconsistency: all of these humanly proportioned people have dog heads. The choice is a familiar one, but unlike, say, in Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Sturm’s characters are visually fuller, with even their dog facial features sometimes drawn with naturalistic contours, making them teeter between actual dogs and Snoopy-esque cartoons. The effect is intriguingly odd, especially when characters are grounded in utterly human actions—how the narrator’s daughter mumbles, “I’m not tired” as she sags on her father’s shoulder on the way upstairs, or the wife’s later, tear-clenched upset over her in-laws exchanging the gag Christmas present of a “Make American Great Again” cap. The dog-faced Trump is a bit much though:

The effect is most overt when Sturm draws his couple’s first romantic episode while wearing paper

mâché animal heads from a summer theater production. He echoes that meta-fictional gesture in some of my other favorite moments of the novel—how the close-up of a painting purchased at a beach town tourist gallery emphasizes a general sameness in style as the larger, partially cartoon world, while also literally drawing attention to the artifice of image as a set of lines and shapes that distort and yet recognizably represent the world. That image-within-an image repeats the fake-animal-head-within-a-fake-animal-head relationship, giving the world of Off Season a similarly almost-but-not-quiet off-ness as a story drawn from inside our actual world—one in which Donald Trump is president too, but doesn’t have dog-like facial features.

Despite its fragmented, episodic structure, the novel is artfully plotted, and so if you dislike spoilers, stop reading now—but I need to address the final chapter, one of the most intriguing of the entire novel. First, it’s brilliant in its aggressive division of visual and textual narration. The title, “Watching a cat cough up a hairball during Suzie’s piano lesson,” subtly re-establishes a conflict-free return to the family structure in which the narrator is once again ferrying children to after-school events—a fact that alone gives the novel closure. Visually, the chapter consists entirely of twenty-seven panels of a cat, presumably the piano teacher’s, in the corner of a room, sometimes vomiting, but mostly just hanging out. The text, which seems to run on an intriguingly unrelated yet parallel track, reveals that the narrator in fact has gone into therapy as his wife demanded and for the first time is dealing with his repressed anger at her for an affair she had when they were newly married but that she only confessed during her severe post-partum depression so that he had no choice but to say he forgave her. The incident is the first and only moment in the novel in which the wife is culpable, a key reversal of the marital power dynamic. Coupled with the ingeniously peculiar division of image narration and the implied improvement in their relations, the chapter would be my favorite of the novel–until the final four panels in which their recovery is revealed to be the result of their microdosig LSD.

That comical non-sequitur could be a perfectly cute punchline to a shorter and far less ambitious story peopled by two-dimensional characters instead of the complex, albeit dog-headed ones Sturm has spent the rest of the novel developing so convincingly. I felt betrayed. Fortunately, four panels can’t erase the pleasure of the two hundred and twenty-some that precede them. Off Season is an emotionally insightful reflection on the challenges of marriage and parenthood, as paralleled and reflected by the turmoil of contemporary politics.

I met Sturm at the AWP conference last spring, and so I can now confirm: his head appears fully human. He also mentioned that he’s a big fan of the Ash Can School, an early twentieth century art movement that focused on working class New York for its subject matter. Strum has combined that aesthetic with his own oddly naturalistic style of cartooning to produce what I can’t resist calling Ash Can Cartoons. His blue collar protagonist and presidential backdrop add to the effect, since the original school was politically driven too. They just didn’t draw dog heads.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Drawn & Quarterly, James Sturm, Off Season

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized