Monthly Archives: August 2016

29/08/16 If Olympians Were Superheroes

First off, Olympic athletes basically are superheroes. Or at least superhumans. They’ve been the standard for physical perfection since Bruce Wayne started his weightlifting regime in the 1930s.

Of course Olympic gymnastics have changed a bit since then:

And though this could be a test whether skimpy little masks can really keep anyone’s identity secret, here’s my superhero in her civilian clothes:

And sporting her favorite bling:

Oh, and in actual flight:

I snipped her ponytail in my image. Otherwise you might notice I flipped one of her photos. Simone Biles prefers to fly upside down.

Aside from all of the Olympic gold medals (she brought home five in August), one of my favorite things about Biles is her height. At 4′ 9″, she’d be one of the shortest superheroes of all-time (excluding of course Atom, Ant-Man, and the rest of the shrinking crowd). Imagine standing her next to one of Rob Liefeld’s creations:

Or, speaking of disproportionate proportions, next to just about any rendering of Power Girl:

At a 104 pounds, Biles is just a ball of muscle. For male superheroes, if not males in general, muscular is pretty much the definition of sexy. It wasn’t always, which means we’re talking culture, not biological programming. For female superheroes, it’s been oddly the opposite. They tend to be strong and yet not look strong. It’s the difference between this:

And this:

And then of course you can always leave the fantasy of Photoshop and look at the real thing:

v

Gold medalist Meng Suping could throw me through a wall. She has literal superhuman strength. But no female superheroes look much like her. Too muscular. Now imagine if Bruce Wayne hadn’t bothered with all that pesky weightlifting and stayed like the skinny guy in all those old Charles Atlas ads:

A scrawny Batman would not look like a superhero. Muscles are part of the standard package:

Though I appreciate the occasional adolescent exception:

So how about an exceptional 4’8″ ball of female muscle joining the next incarnation of the Avengers or Justice League? It would be nice if comic book “physical perfection” included the world’s current definition of actual physical perfection.

Tags: Simone Biles, superheroines

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

22/08/16 If Superhero Bodies Were Real

If superheroes were real they’d look like Olympic athletes. And world heptathlon champ Jessica Ennis-Hill would be near the top of the league. Here she is in actual flight during the long jump at the 2012 Olympics:

I trimmed away the crowd, filled in her uniform, and experimented with a cape and sash:

The cape didn’t work, but other inspiration did:

For the background I expanded my superhero variation on Warhol’s Marilyn and ran it through a black and white filter:

But the best thing about the image is Ennis herself. She doesn’t need a mask and leotard to look like a superhero. Her body is already superheroic. I made the image because I’ve been writing about superhero bodies a lot lately as I finish a draft of my book Superhero Comics out next spring from Bloomsbury. Here’s a recent excerpt:

Because of the visual nature of the medium, superheroes are foremost their bodies, and their costumes are an extension of their bodies. “The Superhero,” writes John Jennings, “is a symbol of power that is reified as the hyper-physical body,” one that is “perfect” and whose “skintight costume seems directly connected to the display, performance, and execution” of its power (59, 60). Joe Shuster, an aspiring body-builder in high school, partly modeled Superman’s costume on strongmen and acrobat leotards, the thinnest and so most body-revealing of real-world costumes—second only to nudity. When attempting “to delimit the elements of the superhero wardrobe,” Michael Chabon accordingly reduces it to “nothing,” a “pseudoskin” that “takes its deepest meaning and serves its primary function in the depiction of the naked human form, unfettered, perfect, and free” (67-8).

Chabon does not examine his use of the adjective “perfect,” but Jennings acknowledges that a “hyper-physical body” embodies a variety of “cultural and social values” and “belief structures” (59-60). Although narratively superheroes are presumed to be intelligent, the superhero body emphasizes physical over mental ability. James Bucky Carter observes, for example, that “the muscular American body” of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s Fighting American is “stressed as an asset over the prowess of the American mind” and that “the American seat of power resides within the vigorous body the creators so obviously favor” (364). The Fighting American, a self-conscious 1950s recreation of the pioneering creators’ 1940s Captain America, is representative of the hyper-masculine body and the plot structure of physical domination that the imagery encourages across the genre. That formula reflects and reinforces a cultural ideology of “machismo,” which psychologists Donald Mosher and Silvan Tomkins define as exalting “male dominance by assuming masculinity, virility, and physicality to be the ideal essence of real men who are adversarial warriors competing for scarce resources (including women as chattel) in a dangerous world” (64). As fantastical embodiments of traditionally defined masculinity, male superheroes express two of the three traits of the “macho personality constellation”: “violence as manly” and “danger as exciting” (61).

Gender ideology also shapes the cultural meaning of the physique. For male superheroes, physical attractiveness and physical effectiveness are merged. As the two qualities are summarized by psychologists Jacqueline N. Stanford and Marita P. McCabe, male superheroes combine “the level to which one’s physical appearance is viewed as pleasing to the eye” and “the degree to which an individual’s body and body parts allow activities engaged in to be successful” (676). A male superhero’s “hyper-physical” body then may be termed perfect in the sense that it expresses both hyper-effectiveness and hyper-attractiveness, embodying the belief that optimal effectiveness and attractiveness should be combined and that a male body is attractive to the extent that it is effective—a concept that reached its apex in the cartoonishly exaggerated male muscularity of 90s superhero art.

Female superheroes disturb gender dichotomies to an even greater degree. If, as Moster and Tomkins write, “affects are divided into antagonistic contrasts of ‘superior and masculine’ or ‘inferior and feminine’” (64), how can a character be both superior and feminine? Fredric Wertham’s 1954 response to Wonder Woman as “a horror type” encapsulates the conflict: because a “superwoman” is “physically very powerful,” she is then also “the cruel, ‘phallic’ woman,” “a frightening figure for boys” and “an undesirable ideal for girls, being the exact opposite of what girls are supposed to want to be”. Although U.S. cultural attitudes have shifted since the 1950s, studies show the same gender discrepancy continuing into the 21st century. Stanford and McCabe report in a 2002 study of mostly white, middleclass U.S. college students that conceptions of ideal male and female bodies differ significantly. Not only were “males’ ideal ratings … larger than for females,” females “wanted to decrease their upper body, while the “majority of males indicated an ideal upper body that was substantially larger” (679, 681). Males also “indicated an ideal middle body that was slightly increased in size,” while females “wanted to decrease it substantially” (679). Despite shifting ideals for female beauty, the expectation of a thin waist has been a cultural constant since the popularity of corsets in the mid-19th century. Ideal female body mass index has also decreased, a trend apparent in Miss American pageant winners from 1922-1999, an increasing number of whom were under nutrition when crowned (Rubinstein and Ballero).

Although a corseted, malnourished body may be physically attractive according to a culture’s beliefs, it cannot be physically effective. Where men combine attractiveness and effectiveness, the two qualities are divorced and even opposed for women. Within the superhero visual system, female bodies are designed to appear weak, necessitating their rescue by strong male bodies. Drawing from centuries of precedents, Siegel and Shuster established Lois Lane as the prototype for the male superhero’s female love interest in comics. In the first six issues of Action Comics, Superman rescues Lois from a firing squad, a flood, a fall from a skyscraper window, and multiple gangsters. In each case, while Lois is unable to protect herself, Shuster draws her stereotypically attractive body in calf-revealing, form-fitting skirts and dresses, and with a strap slipping down a shoulder as she encounters Superman for the first time. Inverting the attractive-because-effective logic of the male body, an appearance of female physical ineffectiveness is attractive specifically because that ineffectiveness invites male intervention. She is attractive because she is weak.

In what sense then can a female superhero have a “perfect” or “hyper-physical” body? Depictions must emphasize one spectrum over the other, and superhero comics overwhelming emphasize perceived physical attractiveness, even when it explicitly contradicts effectiveness. Thus female superhero bodies are, for example, often large breasted, when breast size has either no or a negative correlation to athletic and combat effectiveness. Female superheroes are not drawn to resemble female body-builders—even when the character herself narratively displays the equivalent or greater strength. Superhero worlds provide a range of non-naturalistic explanations for the discrepancy, but when a character is not fantastically enhanced and so not bound by rules of human anatomy, her performed strength still contradicts an appearance of relative weakness through thinly drawn arms and legs. Muscles are somehow not her source of physical strength.

That’s not true of Jessica Ennis-Hill. Just look at those arms. I considered filling in her stomach, but she earned those abs too. Any superhero, male or female, would be proud to sport that body.

Tags: female superheroes, Jessica Ennis Hill, Olympics heptathlon

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

15/08/16 Dividing the Ages of Comics–Is There a Better Way?

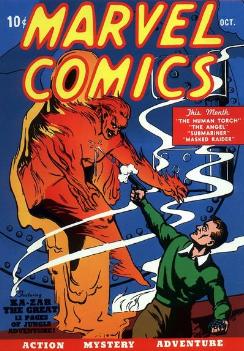

In July 1934, Max Gaines and Eastern Color Printing published Famous Funnies, the first comic strip reprint omnibus in what would become the standard comic book format and so the start point for what has been traditionally called the Golden Age of Comics. The first use of the term is attributed to science fiction author Richard A. Lupoff from his article “Re-Birth” in the first issue of the fanzine Comics Art in 1961.

The Golden Age has no defining endpoint and is sometimes said to be followed by an interregnum period ending with the Silver Age of Comics, traditionally marked by the appearance of the revised Flash in DC’s Showcase #4 (Oct. 1956). According to Michael Uslan, the term originates from a 1966 fan letter in Justice League of America, but the Silver Age division is somewhat arbitrary since it applies only to DC Comics, which was already publishing nine superhero titles in 1956 featuring Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman. The new character Batwoman also appeared three months earlier. The new Flash title, however, eventually led to DC’s 1959 Green Lantern in Showcase #22 and the Justice League of America in the 1960 Brave and the Bold #28, which in turn influenced Charlton Comics and Marvel Comics. Though initiated by DC, the Silver Age is most defined by the early 60s superhero comics of Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, and Steve Ditko published by Martin Goodman’s newly rechristened Marvel Comics, previously known as Atlas in the 50s and Timely in the 40s. From 1961-4 the company introduced the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, Spider-Man, Thor, Iron Man, the Avengers, the X-Men, Doctor Strange, and Daredevil.

Though less defined, the division between the Silver Age and the Bronze Age of Comics is understood largely as a tonal shift, as reflected by Dennis O’Neal’s relatively realistic scripting of Green Lantern Co-Starring Green Arrow beginning in 1970 and by the death of Gwen Stacy in Amazing Spider-Man #121 (July 1973). The Bronze Age also marks an artistic shift. Jack Kirby left Marvel in 1970, and Steve Ditko in 1966, allowing new artists Neal Adams and Jim Steranko to redefine the dominant style. The creative changes may also be understood as a response to a significant market slump, similar to the slump that endangered comics in the mid-50s and led to the resurgence of the superhero genre.

The Bronze Age is most often said to end when DC’s 1985 Crisis on Infinite Earths restructured the multiverse it unintentionally created with the 1956 Flash, while the 1986 publications of Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen mark a further creative shift to what is variously referred to as the Dark Age, Iron Age, or Modern Age, which either extends to the present or is divided in the late 90s when the darker themes emphasized by Moore and Miller ebbed.

In contrast to the ambiguity and competing interpretations of the comics Ages, the Comics Code Authority provides an objective means for dividing superhero comics into historical periods. The Code was created and managed by comic book publishers in an immediate response the 1954 Senate subcommittee hearings on the role of comic books in juvenile delinquency. The pre-Code era then runs from 1934, with the format-defining publication of Famous Funnies, to 1954. Since the Code was revised twice, the first Code era spans 1954 to 1971, the second 1971 to 1989, and the third begins in 1989. Marvel replaced the Code in 2000 with their own rating system, and DC stopped printing the Code stamp on their covers after their 2011 company-wide reboot—formally marking the start of the current, post-Code era. The third Code era is a transitional one, defined by less restrictive guidelines than those of 1954-1989 and a rise of comic books published without Code approval.

Mapping the two historical systems overtop each other, the pre-Code era and the Golden Age and all but the last two years of the interregnum correspond. The first Code era begins two years prior to the Silver Age, ending with the second Code era in 1971, also a common start point for the Bronze Age. The second Code then extends four years into the Modern Age before establishing clear divisions with the third Code and current post-Code eras.

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

09/08/16 I Made This! (Sort of)

Without the 1954 Comics Code, we wouldn’t have the Marvel pantheon of the early 60s. No Avengers, no Spider-Man, no X-Men. We wouldn’t even have DC’s Justice League with the rebooted Flash and Green Lantern of the late 50s. The comics industry created the Code in order to avoid censorship legislation after the Senate held hearings on the corrupting influence of horror and crime comics. As a result, horror and crime comics vanished, and superheroes swooped into the market vacuum.

I’ve been writing a lot about the Code lately. My next book, Superhero Comics, is due out next year from Bloomsbury, and the Code defined the genre for most of its existence. Personally I’d like to replace the ambiguous Golden, Silver, Bronze, etc. Ages with Code-defined eras, but more on that later. I’ve also been tinkering with a one-act play based on the Senate hearing transcripts, with the publisher of EC Comics getting grilled by the senators. EC’s line of SuspenStories got literally blown out of proportion and hung on the walls for photo ops. Johnny Craig’s cover is one of the most famous in comics. Matt Baker’s Phantom Lady is up there too.

Because I was looking at these images so much, I decided to tinker with them as images too. That was my first draft.

Perfectly respectful, but not all that thrilling unless you really zoom in to see how the transparent Code stamp overlays with each cover. But I knew I wanted to use the stamp as a main element.

And I knew I wanted to combine it with the comics that the Code put out of business.

So instead of using the entire images, I started isolating individual figures. This is time-consuming but fairly easy in Word Paint.

You keep whiting-out the edges until you have just the parts you want.

Then the fun part starts. Select, copy, and paste new combinations.

I liked the idea of a sheet of stamps, like the kind I haven’t bought at the post office in years.

Then it was a matter of deciding on the best pattern.

And playing with the framings.

Until just right.

I finished another yesterday using superhero comics from the same period.

Now I’m wondering how it might look on the cover of Superhero Comics.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

01/08/16 Vision and Revision: Tommy and Billy’s Family Tree

Today’s guest bloggers are Thomas Shepherd and his twin brother William Kaplan. They were conceived by Steve Englehart for the maxi-series The Vision and the Scarlet Witch, which ended with their birth (#12, September 1986). John Byrne reconceived them in Avengers West Coast (#51, November 1989), retconning them out of existence. And then Brian Michael Bendis rereconceived them back into existence in New Avengers (#10, February 2006). Their genealogy is equally convoluted, but I’ll let the twins explain:

Our father used to be the Human Torch, a Frankenstein-derivative android who burst into flames in 1939 before fizzling in the late forties.

Two decades later, an evil robot rebuilt his burnt-out body, and he lived another two decades as the Vision.

But then the original Torch erupted from a secret grave, so now Dad wasn’t him but a copy soldered from his spare parts.

Only, no wait, that’s not it either, because next it turns out the Vision and the Torch really are the same person but split in two when a time-traveling supervillain manipulated their timeline. For a while the Vision half was dead and his identity may or may not have been inhabiting the sentient armor of the evil time-traveler’s non-evil teen-age self.

But that was before Iron Man reassembled the original Vision from the scraps She-Hulk made of him after he’d been reprogrammed by our mom to destroy the Avengers (our parents had a really bad divorce). And don’t get us started on whether his/their synthoid body is the kind with buzzing wires and clanking pistons or the kind with synthetic organs that gurgle and fart.

So does that mean our grandfather is Kang the Conqueror (the time-splitting supervillain), Phineas Horton (the Human Torch’s inventor), Ultron (the evil robot—in which case, Henry Pym, AKA Ant-Man, the guy who built Ultron, is our great grandfather), or Wonder Man? Sorry, forgot to mention Wonder Man. Ultron used his brain patterns to erase the Human Torch’s memories and personality from the Vision’s synthetic brain. There’s also that other Vision, some weirdo from another dimension who came here in the 1940s to fight crime, so I guess Ultron used his name and look for spare parts too.

Our mom is the mutant Wanda Maximoff, AKA the Scarlet Witch, and her side of the family is even worse. For a while we thought our maternal grandparents were Miss America and the Whizzer, two Golden Agers who ran with that other Vision guy. It made sense, since the Whizzer and our uncle Quicksilver have the same superpower, plus all that mutating radiation Miss America got hit with.

But then it turns out, no, actually Magda, the gypsy wife of Max Eisenhardt, AKA Magneto, secretly gave birth to Mom and her brother in some Eastern Block country called Transia. Magda died, and so they were nannied by a lady with a cow’s head, who the god-like High Evolutionary made. Bova tried to pass the babies off to the Whizzer after his wife died giving birth to a stillborn, but he freaked out and split.

Mom and her twin brother went back into suspended animation for a while, then High Evolutionary thawed them out for Django and Marya Maximoff, who named them Wanda and Pietro.

Villagers thought Mom was a real witch and drove her out with pitchforks, and then her real father Magneto adopted her and Quicksilver into the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants.

Only, no wait! That’s not it either, because now it turns out the Maximoffs really were their parents, but instead of being mutants, they’re just normal humans that High Evolutionary experimented with. So that’s four sets of grandparents just on Mom’s side.

But if High Evolutionary is our grandfather, then the elder god Chthon is too. He was the Devil before Lucifer drove him out, but he preserved a part of his essence in Mom, which is how she got some of her probability-altering “hex” powers. Since it was her hex powers that allowed her to conceive us, we must be part-Chthon. Though some of that hex stuff must have been High Evolutionary’s mutant-like alteration, so, subtracting our temporary adoptive grandpas Whizzer, Magneto, and Django, we still have two different kinds of reality-bending grandpa magic in our genes. Unless it really was Mom’s channeling the “Magick” of the witches of New Salem when she got pregnant, like she thought at the time. Dad was holding onto her, so when the Magick circled them, his DNA was in the mix too. (Some of the witches of New Salem looked like High Evolutionary’s animal-people, but I think that’s just one of those weird coincidences.)

But, no, hold on, instead of Magick or Chthon essense or High Evolutinary’s mutant-like hex powers, it turns out my brother and I were really pieces of Master Pandemonium’s lost soul, the one he traded to get superpowers from Mephisto (another Devil but not the same Devil as Chthon). Mom grabbed onto them by accident when she was wishing us into existence. When Master Pandemonium got hold of us again, he turned us into evil hand puppets and shot flames out of our mouths.

That sucked. But then Mephisto showed up, and guess what! We weren’t pieces of Master Pandemonium’s lost soul after all—Mephisto just made him think that.

We were really lost pieces of Mephisto’s lost soul, which got shattered by Invisible Woman and Mr. Fantastic’s little boy, Franklin Richards—a kid who, believe it or not, is even more messed up than we are. Since Franklin’s the one who fragmented us into existence as soul pieces, I guess he’s our grandfather too.

_Fantastic_Four_and_Power_Pack_Vol_1_1.jpg/revision/latest?cb=20140630232458)

Anyway, we only existed when Mom was thinking about us, which meant when she was in the middle of a battle or knocked-out we would fade away—which apparently freaked out a few babysitters. Mephisto stole us back from the Master Pandemonium, but then our mom’s mentor Agatha Harkness came back from the dead and defeated Mephisto by erasing Mom’s memory of us. That didn’t last though, because after a version of Kang—not his teen-self but another version named Immortus—filled her with even more superpower, she goes all crazy and de-mutants most of the planet because she’s so upset we never existed. That’s around when she reprogrammed Dad too.

Only, guess what? We do exist! Because when Mom rebooted things after going crazy, she unknowingly rebooted us too. That time she used the extra power Kang-Immortus gave her, so now he’s on both sides of the family tree, which sounds incestuous but isn’t. Instead of giving birth to us again, Mom sent our reincarnated selves out to be born to completely different mothers. That’s why Tommy’s last name is Shepherd and Billy’s is Kaplan.

So even though we are identical twins, we have three mothers, four fathers, five paternal grandfathers, six maternal grandmothers, eleven maternal grandfathers, and no paternal grandmothers.

Or at least we did until the Marvel universe was wiped out in 2015. Now we don’t exist again, and our parents don’t know who any of us are or were or will be next. How do you draw that on a family tree?

Tags: Scarlet Witch, Thomas Shepherd, Vision, William Kaplan

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized