Monthly Archives: June 2019

24/06/19 In French, the masculine takes precedence.

Reading the English translation of Julie Delporte’s This Woman’s Work makes me wish I could read it again in its original French—not for any imagined flaw in its translators’ fluid prose, but the opposite: I can’t imagine this intensely personal memoir existing in any different form.

No translation is simple. Every language has not only its own sounds, but no two words share exactly the same set of connotations either, even when their dictionary definitions appear identical. Sometimes differences are overt, as when Delporte declares: “the grammar I was taught still hurts,” she must add an explanation in an asterisked note at the bottom of the page: “In French, the masculine takes precedence.” It would be a fitting subtitle for her memoir.

Graphic works add another level of complexity to language because a choice of font—something readers of prose-only novels hardly register—is a visual element embedded into each page. Translating the effects of graphic design is even more complicated when the words aren’t contained by talk balloons and caption boxes of conventional comics. Delporte’s words are all unframed. Her script winds around and between and sometimes overtop her drawings in similarly penciled lines, dissolving the differences between handwriting and drawing style, diary and sketchbook. Few comics are composed of more thoroughly integrated image-texts.

Whether composing letters or images, all of Delporte’s lines are evocative lines, each color carefully chosen. When she depicts herself having sex with a lover in an attempt to become pregnant, her drawn self exists only in blue pencil and he all in orange, their lines almost but not quite touching. When she lists the promises she wishes he had said to her afterwards, most expectant mothers would probably like to hear the three she scripts in blue: I’ll take care of her, change the diapers, nurse her. But Delporte pencils the most important unsaid assurance in orange: “You’ll be able to draw.”

Delporte is a female artist documenting her private and professional search for her own place in a male-dominated field and world. The search is life-long and takes her in a non-linear path around Europe and North America and deep into her own past. She fills her story with personal reproductions of works by female artists, each linked to critical moments in her own life. When she imagines having to raise a child on her own, she sketches a Mary Cassatt painting of a mother holding a child, giving the image a double meaning since it both represents her possible self and the artistic lineage she is constructing. Delporte travels to Finland to write about Tove Jansson, the creator of the Moomins, cartoon trolls who are “happy idiots who forgive one another and never realize they’re being fooled.” That description is Tove’s, but for Delporte it encapsulates the role of women. She claims she’d “give almost anything to be like” the Moomins, but her memoir is her struggle to escape that past—including the darkest moments of her childhood. She received her “first lesson in sex” by a slightly older cousin, but when she later dreams about the trauma, it’s not the event but how the adults in her family never responded, never spoke about it. Now she looks at her family tree and wonders: “which of these women were raped?”

Delporte travels to Finland to write about Tove Jansson, the creator of the Moomins, cartoon trolls who are “happy idiots who forgive one another and never realize they’re being fooled.” That description is Tove’s, but for Delporte it encapsulates the role of women. She claims she’d “give almost anything to be like” the Moomins, but her memoir is her struggle to escape that past—including the darkest moments of her childhood. She received her “first lesson in sex” by a slightly older cousin, but when she later dreams about the trauma, it’s not the event but how the adults in her family never responded, never spoke about it. Now she looks at her family tree and wonders: “which of these women were raped?”

That central trauma permeates but does not define Delporte’s work. The memoir is much more of an attempt to construct something new, even if it is necessarily incomplete and tentative as she wanders between continents and decades of memories. When she grows frustrated with writing and drawing, she turns to ceramics for something more tangible. The pages of her memoir have a similarly tangible aesthetic. The ghostly edges of transparent tape seem to hold the scissors-cut images in place. Some words are written on strips of paper, their near-whiteness almost but not quite matching the white of the book’s actual paper. Several pages are reproductions of her sketchbooks, their bent corners creating a book-within-a-book illusion.

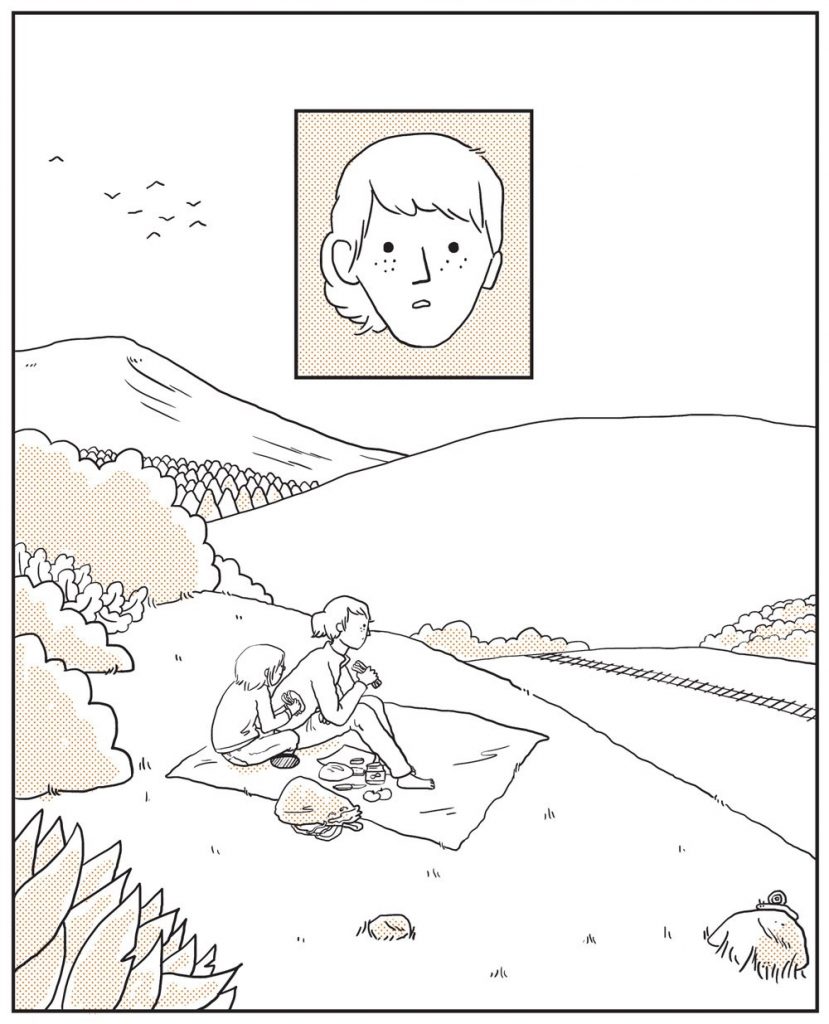

Some of her images are precisely finished, while other seem gestural and preliminary, a face left blank within the frame of a head. That incompleteness is essential to the larger project, as when she describes herself “struggling to draw” her own vagina because she “lived so long without an image of one.” She sketches the character Rey from Star Wars for the same reason, delighted to see “a self-sufficient woman, on the screen.” When she was growing up, she only had Wynona Ryder playing Jo in Little Women, a character who marries an older, more accomplished man—the plot closure Delporte now rejects.

She also varies her layout style, creating a cramped intensity for pages relating her physical travels, but rendering certain memories and dreams more sparsely. Her hand-written script grows in size too, with only a few words filling an entire page, often juxtaposed against a single image on the facing page. The switching styles give the memoir a visual rhythm, while also accenting the literally larger-than-real-life content. Delporte dreams of magically appearing babies, and strange bristles growing from her legs, and stabbing a polar bear in the heart to save her own life—each a bright fragment in the not-yet-complete puzzle of her search.

It’s fitting that this French memoir ends with a dream sequence situated around an untranslated term. A community of female poets live in a “béguinage,” a building complex for religious lay women who don’t take the vows of nuns. Though Delporte earlier glossed the male-dominance of French grammar for English-only readers such as myself, here she appropriately leaves us to find a dictionary ourselves. But this utopian vision, where women work together making art and raising children who venture out into the world when ready, ends on a far more ambiguous note—a page seemingly torn from Delporte’s sketchbook diary as she draws herself in bed while her lover sleeps downstairs because they’re just fought. She writes: “I’m scared to death I’m pregnant.”

That poignantly open-ended conclusion seems the best closure possible for a memoirist still struggling to make her life work.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

10/06/19 A New Dynamic Duo

Sales of Charles Forsman’s 2013 End of the Fxxxing World spiked last year with the Netflix release of the eight-episode British adaptation. Originally serialized in French, Max de Radiguès’s Moose premiered in the U.S. in 2014, followed last year by Bastard. Where Forsman draws two teen runaways, Radiguès focuses on a bullied teen and then a mother and young son running from the law. Their collaboration, Hobo Mom, takes those elements and scrambles them into the tale of an absent mother returning to her estranged husband and daughter. In terms of both subject matter and style, it’s difficult to imagine two comics artists better suited to work together.

I’m curious how the authors evolved their story content and the idiosyncratic back and forth of conceiving characters and developing situation and plot, because the finished pages erase that dimension of their collaboration. If the two worked from a script, no hint of it remains. But I was surprised at how seamlessly the pages also merge and so disguise the artistic process. While collaboration is standard in comics, scripter-artist combinations are more typical, and when two artists collaborate, one is often the penciler and so the primary visual storyteller laying out pages and panel content for an inker to finish. (An exceptional exception is the 1988 Havok and Wolverine: Meltdown mini-series, where painters Jon J. Muth and Kent Williams divided not only pages but areas of panels, inserting their distinctively drawn primary characters into the other artist’s visual environment.)

Opening Hobo Mom, I expected a similar distinction, with the marks of each artist clearly defined at the page and pen levels. The graphic novel instead presents artwork so unified it seems to have been created by a single author. The success of the merged style is due in part to the artists’ already similar tendencies. Both work in black and white, with simple, clean lines and virtually no cross-hatching. Their settings are minimal and their figures largely naturalistically proportioned, and while facial features obey cartoonish conventions of exaggeration, the degree is relatively slight. But it’s those distortions that identify each artist: the wide, round jawline of Forsman’s father, the small, triangle nose of Radiguès’s mother. Appropriately, the features of the daughter are more difficult to differentiate, as if the two artists, like their stand-in parents, have merged at the DNA-level of the line.

Layouts are equally merged, with a range of constantly varying rectangles, sometimes gridded in 3×2 or 4×2, other times in uniform rows of shifting panel counts, often with sizing accents on images enlarged by merging panels within an implied grid. Because the frames and internal figures share the same line quality, with the sparse whiteness of a background identical to the white of the margins and gutters, the shifting layouts not only shape the story content but take on a visual significance of their own. The authors occasionally add blocks of black, usually in night scenes or to distinguish objects, plus the slight color effect of hazy pink Benday dots to define shadows. But rather than adding richness to the images, the minimal techniques emphasize the starkness of the artwork.

The artists also treat pages as the primary units of composition, ending scenes on final page panels and giving the overall book a visual rhythm synchronized to page turns and the gutter of the book spine. When, for instance, the daughter spends two pages feeding her pet rabbit, the scene ends on an enlarged panel revealing that she has climbed inside the enclosure, the angled grid of the fencing evoking the gridded frames of the layout in a way that indirectly suggests why the mother left in the first place. The facing page expands that visual suggestion with a full-page image of a train in an open landscape. A later scene change employs a similar leap, with a 3×2 page of the parents arguing over whether the mother can stay followed by a full-page of the family seated at dinner. After two two-page spreads of night-darkened interior panels culminating in a one-panel sex scene, the page turn marks a scene leap to the next day, with the mother and daughter outside in a white-dominated landscape.

While there are no formal chapters, a visual motif of a pull-page panel with a single inset further punctuates the novel, producing an additional rhythm that culminates in a mother-daughter pairing near the climax. While the novel is largely dialogue-driven with no narrating text, later page sequences switch to a purely visual approach that expands the emotional tension through images of silently content mother-daughter interactions in natural landscapes and the brooding father alone in his truck with visions of his wife. The most ambitious page in the novel pairs a close-up of his face with a contextless nude of the mother. Because the face consists of two black circles for eyes and a continuous squiggle of a line to form nose and mustache, the close-up pushes style into nearly pure abstraction—intensified by the naturalistic shape of the more distant nude and its hair-obscured face. For a moment I forgot I was reading a novel and not poring over a concept-rich graphic design (which I guess I was).

While the novel is successful both in its minimalistic visual approach and its realistic treatment of the emotional dynamics of an estranged but well-intentioned family, I still question the premise of its high-concept title. Since the word “hobo” evokes Depression-era homeless men hopping rides on agricultural trains, I assumed this contemporary story would use it only metaphorically, the phrase “hobo mom” evoking the title character’s inability to remain in the rabbit cage of traditional motherhood. But, in fact, no, the mother’s opening scene is literally set on a train, in one of those inexplicably empty cars with a sliding side door ubiquitous in film lore. She also faces a would-be rapist who tears open her shirt to expose her cartoon breasts before she manages to shove him out into a dust heap beside the rails. The burly rapist is apparently a “hobo” too, imported from the same bin of clichés, making any metaphorical or thematic reading of the word and its reflection on the mother’s character difficult.

Here I suspect Radiguès, who lives in Brussels, may be the primary hand at work, since the Depression-era tropes are reminiscent of westerns written by European authors who preserve their own pseudo-version of U.S. historical fiction in an even more distorted form. But who knows? Perhaps Forsman, who lives in Massachusetts, has a thing for trains and hobos.

Happily, this one too-literal scene only briefly mars an otherwise warmly intelligent drama as the returned mother tries to make amends and reintegrate into a lifestyle that continues to grate against her wandering impulses. Since her husband is a locksmith who drives a truck adorned with the wordless logo of an antique key, and the daughter plays on a swing made from a tire tied to a tree branch, readers can probably sense the plot trajectory of those metaphors, but the pleasure is in the author’s dual execution.

[A version of this post and my other recent reviews appear in the Comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Charles Forsman, Hobo Mom, Max de Radiguès

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

03/06/19 Why Don’t I Like Donald Trump?

This is a sincere question asked recently by a fellow member of the Rockbridge Civil Discourse Society. Usually I’m surrounded by family and friends who take the answer for granted, but RCDS is a group of Democrats and Republicans trying to build understanding across the partisan divide. Which means I have to give the question more serious thought than I would normally. That’s a good thing. Having to explain myself to someone who doesn’t already agree with me is an even better thing. So this is my sincere attempt at a thoughtful response.

- I didn’t like Trump before I didn’t like Trump.

Before he was a politician, I knew Donald Trump only as one of those self-fulfilling celebrities famous for being famous. I never watched an episode of The Apprentice, but everyone knew the one-man promotional brand playing himself on TV. I categorized him in my head with Hulk Hogan. Saying I didn’t like him is misleading. He was no more real or relevant to me than Paris Hilton or a Kardashian. Except his caricature was even less savory. A serial adulterer marrying absurdly younger trophy wives while flaunting his comic wealth. None of this has anything to do with politics. It never occurred to me to wonder what political party he might belong to because political parties involve groups of people banding together to pursue common goals. The goal of Trump was exclusively Trump. This was before 2014—before I knew he was running for office. At first I didn’t believe it, not really. It had to be another gimmick product, Trump Wine, Trump University, Trump for President, one more way to expand his business brand, pump up his ratings with more outrageous showmanship. It didn’t occur to me that he could win a primary let alone a nomination. It didn’t occur to me that someone, anyone, could view him as anything but a pop cultural personification of ostentatious greed, because I sincerely understood him to be that and only that.

- Trump says things that aren’t true.

Some people call that lying. Others say he’s only using exaggerations—or just savvy business practice. Whatever you call it, Donald Trump knowingly and wantonly makes statements that are not true. He also knowingly and wantonly makes statements that are true. The accuracy of his statements is irrelevant. He says whatever is most useful to him. His 1987 memoir ghost-writer called it “truthful hyperbole,” a way of playing “to people’s fantasies,” “a very effective form of promotion.” Admittedly, an indifference to truth sounds useful in a cutthroat business environment, and as long as Trump remained in that environment, his exaggerations, lies, and hyperboles were no concern to me. Then he became a politician, a profession known for its own brand of mistruths. But Trump is different. Look at all the presidential nominees of my adult life: Mondale, Reagan, Dukakis, Bush, Clinton, Dole, Gore, Bush, Kerry, Obama, McCain, Romney, Clinton—all of them were constrained within a similar range of allowable spin. I’m not arguing any are better, more honest people. If they could have gotten away with Trump’s level of mistruth, they probably would have. But his go unpunished. Maybe it’s his business savvy, his ability to sell anything, but its application to U.S. politics deeply disturbs me. Again, this has nothing to do with political parties. If Donald Trump had run as a Democrat, he would be the same democracy-gaming salesman appealing to a slightly different set of voters with a slightly different set of self-promotional hyperboles.

- Trump says things that offend me.

I’m not going to say Donald Trump is a racist. Conservatives tend to define that term as a necessarily conscious belief, that only a white person who actively believes he is superior to non-whites can commit racist acts. I don’t know if that describes Trump or not. I suspect when he refers to Central Americans as rapists, murders, etc., he is not expressing deeply held personal convictions but politically useful hyperboles of the kind discussed above. That doesn’t make it any less offensive to me. I also don’t know if he ever committed sexual assault, but I know he bragged that he did. Some defended his words as “locker room talk,” that it’s normal and therefore okay for men in the privacy of other men while unaware of being recorded to brag about assaulting women. I never have, and I have never heard any male friend or acquaintance of mine brag about assault either. Maybe I’m the wrong kind of man. Maybe Trump is no different from all our other white male presidents, saying out loud what the rest privately thought and privately committed. If so, then they all offend me equally. Again, this has nothing to do with political parties. No one who brags about sexual assault and expresses offensive stereotypes about ethnic groups should be electable, and I’m offended that Donald Trump got elected anyway.

- Trump thrives on the political divide.

It never even occurred to me that he would keep using Twitter after the election. It never occurred to me that he would continue to attack and mock his political opponents at literally a daily rate. Maybe I’m just old. I remember when George Bush’s campaign rhetoric went into panic mode a week before the 1992 election. He said, “My dog Millie knows more about foreign policy than these two bozos.” He nicknamed Gore “Ozone Man” because “we’ll be up to our neck in owls and outta work for every American.” Those sound like presidential tweets now, and during a Trump presidency, it’s always a week before the election. I’m not suggesting Trump created the political divide. Exactly the opposite. He got elected because the divide was already so extreme, and he is the perfect salesman to thrive in that political marketplace. And even this isn’t about political parties. I want a president—preferably a progressive one—who tries to bridge differences, not focus exclusively on his base by stoking their outrage in an endless get-out-the-vote campaign.

- I don’t like his politics.

Now, finally, this is about political parties. I’m a Democrat. Democratic candidates more often reflect a larger number of my political preferences than Republican candidates. That’s an absurd understatement. I have never seen a Republican candidate that came even close—though McCain during the 2000 primaries did make me sit down and really look at his plank-by-plank platform. I long for that. Still, if Romney had been elected in 2012, or McCain in 2008, or Dole in 1996, I wouldn’t have responded to their presidencies in any way like I’ve responded to Donald Trump’s. When Bush was reelected in 2004 and elected in 2000, and when his father was elected in 1988, and Reagan in 1984, I had voted against them but accepted the outcomes with disappointment and only disappointment. November 2016 was nothing like that. I felt personally betrayed. I felt that the norms of decency had either been overturned or revealed to have never existed. Even when Clinton’s polls dropped three points after the release of the Comey letter in the last days of October, it still never seriously occurred to me that Donald Trump—a man who to me represented misogyny, bigotry, narcissism, and greed—could be elected. Clearly, I was wrong. But I maintain that it is not possible for anyone to have voted for Donald Trump if they understand Donald Trump to be the person I understand him to be.

And maybe I’m wrong about that too. Maybe my impressions of him from the 80s and 90s and early 2000s unfairly biased and blinded me to his real character on the campaign trail. Maybe I have an idealized, antiquated notion of proper politics and my disappointment isn’t against Trump’s divisive style but the political arena that makes it effective. Maybe most or all white men who rise to power are at least latently prejudiced and abusive, and Trump has merely revealed that fact. Maybe it’s okay to use mistruths when it’s for a cause you and your followers deeply believe in. It’s also possible that my dislike for Donald Trump is really motivated by political preference, and that if a Democrat with the same traits had risen to power I would have accepted his shortcomings and supported his agenda. I hope not. But I fear it is possible. It’s also one of the things I most dislike about Donald Trump. He’s motivated a lot of good people to embrace a lot of very bad things.

- 4 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized