Monthly Archives: January 2021

25/01/21 Nothing Ages Faster Than the Future

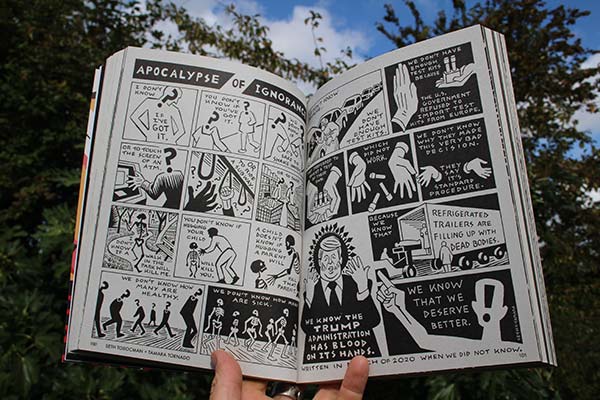

A year ago it would have been hard to imagine a comics magazine with a taste for futuristic political dystopia overshadowed by the actual Armageddon of daily headlines.

When World War 3 Illustrated #51: The World We Are Fighting For was released last September, news reports were an apocalyptic smorgasbord: west coast in flames, world pandemic death count nearing one million, yet more tear-gassed BLM protestors, and a president fanning his weekly scandals on Twitter. Four months later, and the U.S. covid death count is over 400,000, Congress was physically attacked by rioters, and the former president prepares for his second impeachment trial.

Cartoon science fiction and political parodies seem pleasantly quaint in comparison.

Of course, when World War 3 Illustrated took its name in 1980, the world was braced for an actual Armageddon as the U.S. political landscape lurched hard to the right, upending the Cold War with it. Comics authors and editors Peter Kuper and Seth Tobocman found their archvillain in Ronald Reagan—a president who even Democrats might have embraced in November to avoid another stranger-than-science-fiction term of Donald Trump.

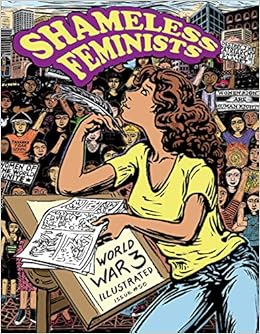

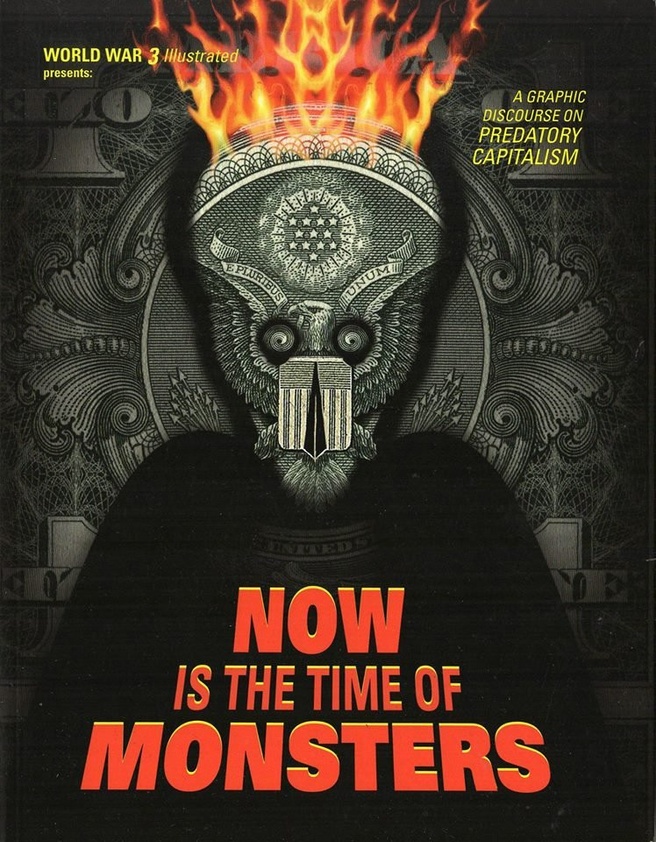

As Reagan sinks into ancient history, World War 3 Illustrated has continued to evolve as a living political document expressing the struggles and aspirations of its leftist activist-artists. Like the two previous issues, #51 is a book-sized annual, compiling a dizzying array of work by nearly forty creators. After 2019’s Shameless Feminists and 2018’s Now Is the Time of Monsters, the editors (founders Kuper and Tobocman are joined by Ethan Heitner) envisioned something more uplifting: a tribute to “the humane socialist vision of Bernie Sanders,” who last fall (when the issue was planned) appeared to be on his way to claiming the Democratic nomination and a November face-off with “the fascist future of Donald Trump.”

That alternative timeline diverged with an even more unimaginable premise: the Biden-Harris ticket. But the distance between our actual political present and the one World War 3 Illustrated longs for makes The World We Are Fighting For that much more compelling. No one predicted the CV-19 pandemic or the international George Floyd protests or Donald Trump’s sixty voter fraud court cases, but those instabilities are also opportunities. “Another world ACTUALLY IS possible,” the editors argue, and, more importantly: “That world is up for grabs.”

The 220-page issue features several authors that previous readers should appreciate returning: Sue Coe, Eric Drooker, Ben Katchor, Kevin Pyle, and of course the editors themselves. Most names are new to me, in keeping with the editors’ efforts to find and showcase new talent. The comics vary widely in length, from the single-digit sequences of Elizabeth Haidle, Jackie Lima, Terry Tapp, to the double-digit narratives of Sandy Jimenez and, the longest, Tobocman’s own twenty-six page retrospective.

I especially admire the one-page artworks of Coe, Meredith Stern, Joes Sances, and Mohammed Sabaaneh—all of which evoke the expressionistic woodblock styles of past political movements, an effect further strengthened by the images’ white lines printed on the volume’s black pages. Single images also allow faster turn-around, so, for instance, Coe’s June-dated image of Trump watching police beat protesters as he stands with a raised Bible is a clear reference to the clearing of Lafayette Park before his St. John’s Episcopal Church photo-op.

Other comics acknowledge the unexpected shift in reality in literal post-scripts. After Sasha Hill and Annabelle Heckler tell the story of squatters eventually purchasing abandoned Brooklyn buildings and transforming them into thriving communities, they add a pair of pages to show the continuing collective efforts in the face of the pandemic and the disproportionate hardships of the spring lockdown.

Steve Brodner’s “The Greater Quiet” was long conceived well after the editors’ original vision.

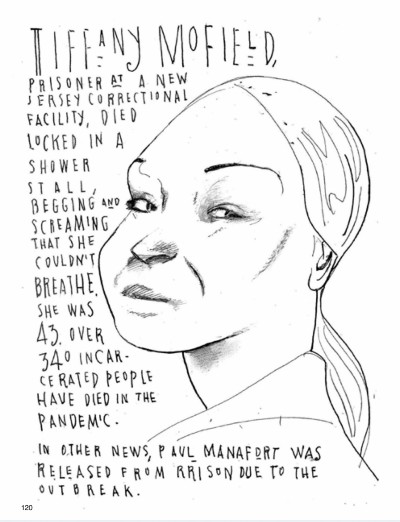

Brodner offers a half dozen caricature portraits of “those lost in the pandemic,” including a Walmart employee, a nurse, an incarcerated woman, a grocery clerk, a geriatric psychiatrist, and a hospital manager. Mac McGill’s “The Virus” tackles the topic through five full-page Trump portraits that evolve from swirling comb-over to CV-19 microbe in a balance of representation and abstraction.

Though primarily focused inwardly on the U.S., the issue also gestures toward international connections. Argentina-born artist José Muñoz provides the watercolor cover depicting his memory of La Pampa providence. John Vasquez Mejias’ excerpt from “The Puerto Rican War” is a study in woodblock-style of the colonial history and fight for independence of the territory the U.S. claimed at the end of the 19th century. Susan Simensky Bietila’s “Water Protectors” documents the struggles of the Menominee and Ojibwe tribes in northern Michigan and southern Canada, and Nere Kapiteni and Rebecca Migdal set their Trump parody in Antarctica where Donald and Melania have been exiled on a floating island of ice because no nation will accept them.

The issue is also bookended with the colorful comics of Colleen Tighe and Peter Kuper, giving The World We Are Fighting For a fittingly vibrant entrance and exit. The eclecticism is difficult to summarize, as every few pages offer some new and boldly different artistic style and storytelling vision. Yet they all cohere in the political thrust of the magazine’s political mission and artistic call-to-arms. Although Bernie Sanders did not become the 46th president this month, the U.S. has so far avoided the Civil War that even the creators of World War Three Illustrated didn’t want to imagine.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

18/01/21 The Vices of Representing the Vice President

Vogue is featuring Vice President Kamala Harris on its February covers. Vanessa Friedman of the New York Times describes the photo on the digital cover as a “more formal portrait of Ms. Harris in a powder blue Michael Kors Collection suit with an American flag pin on her lapel, her arms crossed in a sort of executive power pose against a gold curtain.”

But it’s the photo on the print cover that received criticism as soon as the magazine released a preview in early January. Friedman writes: “Ms. Harris chose and wore her own clothes. The selected photo is determinedly unfancy. Kind of messy. The lighting is unflattering. The effect is pretty un-Vogue. ‘Disrespectful’ was the word used most often on social media.”

Apparently, Vogue unexpectedly swapped covers, placing the less formal version on the more prominent print edition, without telling Harris in advance: “The team at Vogue loved the images Tyler Mitchell shot and felt the more informal image captured Vice President-elect Harris’s authentic, approachable nature — which we feel is one of the hallmarks of the Biden/Harris administration.”

Friedman responds: “Ms. Harris may be authentic and approachable, but she is also about to become the second most powerful person in the country… She is, no matter what happens during the Biden administration, a game-changing participant, one that belongs on a pedestal.”

Prior to seeing the Vogue covers, I was digitally adapting photos of Vice President-elect Harris, as part of my ongoing experiments in abstraction using the aggressively antique technology of MS Paint. While the images are all certainly “un-Vogue,” some are also “messy,” and perhaps “unflattering”–though the intent isn’t the exaggerated distortions of visual critique. They’re not political cartoons in that sense. The distortions aren’t meant to communicate disrespect, but I doubt any belong on an art gallery pedestal either.

Representation usually requires resemblance: an image of a person is an image of that person because the image looks like that person. But representation also involves distortion: a two-dimensional photograph can never be a replica of a three-dimensional subject, even before factoring in elements of framing and perspective and lighting and the fleeting fragment of time it impossibly freezes. My images distort a lot further by literally abstracting (removing) pixels and then rearranging and duplicating them in evolving patterns, creating images further and further removed from their photographic source material.

When does an image of the Vice President stop representing the Vice President because the image no longer sufficiently resembles her? I’m searching for that answer.

- 3 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

04/01/21 What My Top Posts of the Year May or May Not Say about 2020, the Internet, and Me

I started this blog in the fall of 2011. It received a little over 18,000 views its first full year, a little over 32,000 last year, and 235,681 total. It is a tiny tiny corner of the Internet. I named it after a novel I drafted in 2011 and was hoping to promote. The novel remains unpublished, though I now have an agent submitting a graphic novel to London publishers, so my fingers remain permanently crossed. Since starting the blog, I’ve also published five academic books about (mostly) comics, including one out later this month (Creating Comics). A sixth is under contract for 2022. The first was a revised version of the blog’s first four years. Some of those posts still get the most views—not just in total, but each year. Here’s my 2020 top ten:

-

- Analyzing Comics 101: Layout

- Science Fiction Makes You Stupid

- Is Harry Potter a Superhero?

- Ferris Bueller’s Missing Sex Scene

- Why I Asked my University to Remove ‘Lee’ from its Name and my Town to Remove ‘Stonewall Jackson’ from the Name of its Historic Cemetery

- Hundred-Year-Old Racist Superman from Mars

- A Brief History of the Pornographic Superhero

- The Best (and Worst) Superhero Sex of All Time

- Why I Shouldn’t Be Fired for Teaching Comics

- Analyzing Comics 101: Rhetorical Framing

Only one of those was newly posted in 2020, which means the rest attract attention from somewhere other than the weekly links I post on my Facebook page, Twitter account, and my university’s campus notices. Seven of the ten are also high on my blog’s all-time top list:

-

- Science Fiction Makes You Stupid

- Is Harry Potter a Superhero?

- The Best (and Worst) Superhero Sex of All Time

- Hundred-Year-Old Racist Superman from Mars

- Analyzing Comics 101: Layout

- Jean Valjean, Wolverine, and What Boys (Are) Like

- Carrie White Vs. Jean Gray

- Why I Shouldn’t Be Fired for Teaching Comics

- Are Batman and Robin Gay?

- Layout Wars! Kirby vs. Steranko!

- Ferris Bueller’s Missing Sex Scene

Two have the words “sex” or “pornographic” in the title, which I’m guessing are very popular search engine terms. Type in “superhero” next to either and apparently my blog appears somewhere in the results list. The 2018 Ferris Bueller post has “sex” in the title too, so another mystery solved. I’m really not sure why Harry Potter is still getting so many hits in 2020 (I wrote it back in 2013), or, more weirdly, John Carter of Mars (though it did annoy some Edgar Rice Burroughs fans in 2012 when I published the post-colonial critique of the novel and film). My unfortunately click-bait titled “Science Fiction Makes You Stupid” got unexpected international attention in 2017, including from annoyed SF fans—though the actual post and the cognitive science research study it describes (as well as the follow-up study) should make a SF fan (like me) happy. At least the two “Analyzing Comics” make sense since analyzing comics is mostly what I do here. “Why I Shouldn’t Get Fired for Teaching Comics” is from 2019, so the youngest post on the all-time top ten and the second youngest for 2020. It was my response to an essay written and distributed by an alum suggesting that my courses and I be eliminated for dumbing down the W&L curriculum.

The outlier is “Why I Asked my University to Remove ‘Lee’ from its Name and my Town to Remove ‘Stonewall Jackson’ from the name of its Historic Cemetery” because it’s the only top-ten post from 2020 that was actually published in 2020. Since I wrote it in July, my town has renamed the cemetery. A statue of Stonewall Jackson was also removed from the Virginia Military Institute, the college literally next door to mine. My school’s board of trustees has not yet made a decision regarding our name.

I wrote “Why I Asked” for Rockbridge Civil Discourse Society, a Facebook group that I co-founded and was still moderating until fall. The group was designed to foster conversation between folks coming from opposite sides of the political divide. The issues of statue removals and name changes was getting a great deal of attention on the page, and the post was my attempt to explain my positions in a way that I hoped a conservative could at least understand (though almost certainly not agree with).

I had written “Why I Don’t Like Trump” in 2019 for the same reason: a conservative member of RCDS sincerely asked my why I didn’t like Trump, and I gave him the most thoughtful, non-inflammatory answer I could. I republished it in October—which is why “Why I (Still) Don’t Like Trump” hit sixteen on my top posts of 2020. Number fourteen was “How Rightwing Pundits Destroyed America and my Facebook Page,” published the same month. After moderating RCDS for three years, I got a little tired out. My farewell, “Things I Learned from Civil Discourse,” only hit thirty-one. It’s a list of best practices for trying to engage in political conversation with someone who doesn’t vote like you. Very few folks on the page follow them.

I also got a bit obsessed with poll watching in 2020, publishing a four-part series “Predicting the Next President,” which mapped the polling shifts and Electoral College predictions. It ended with “After Math: So How Wrong Were the Polls?” Short answer: pretty wrong.

I published twenty-four reviews of graphic novels. Since I started writing reviews at PopMatters.com three years ago, those reviews have dominated my personal blog too.

Another eighteen posts focused on other kinds of comics analysis, my own comics, my creative process, comics I helped publish through Shenandoah, plus one comic my daughter made during the lockdown with one of her former students whom she was nannying after their pre-school was forced to close because of the pandemic.

There were also six posts about zombies.

Weird fucking year. Glad it’s over.

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized