Monthly Archives: November 2017

27/11/17 Comics Journalism and the Refugee Crisis

British cartoonist Kate Evans documents the lives of refugees stuck in French detention camps as they long to complete their journeys to England. Her narrative spans from October 2015, when Evans first volunteered in the French refugee camp known as the “Jungle,” to September 2016, when the British government began construction of a wall in Calais to prevent refugees from stowing away in cars aboard ferries leaving the French port for Dover twenty miles across the English Chanel. The first chapter also began as the 14-page comic “Threads. The Calais Cartoon.” Evans distributed 12,000, crowd-funded copies to refugee support groups which sold them to raise further funds and public awareness. Later chapters also focus on the unnamed refugee camp in Dunkirk thirty minutes east of Calais.

On her first trip, the camp is barely functional, only 24 toilets for 5,000 inhabitants. Evans helps construct temporary housing until her supply of staple-gun staples runs out. On her second trip three months later, the former “tool tent” is a warehouse of prefab house frames and electric saws. But in Dunkirk a month later, police enforce a tents-only mandate, preventing volunteers from entering with dry sheets and wood planks to raise tents from the inches-deep swamp of the former suburban park.

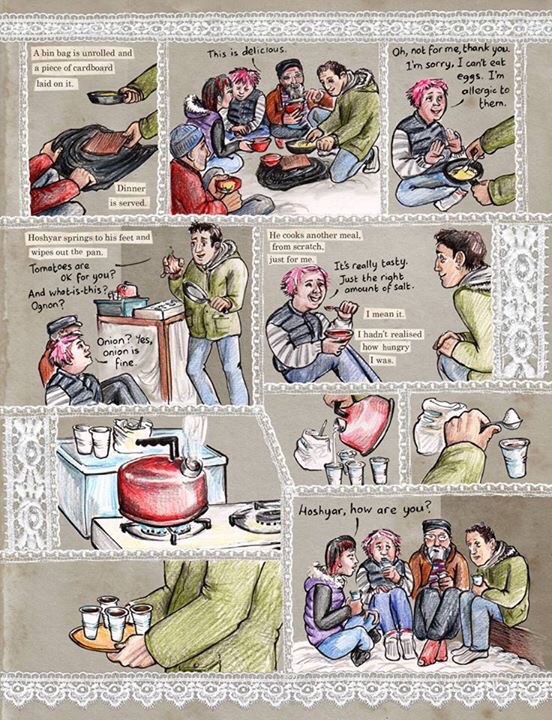

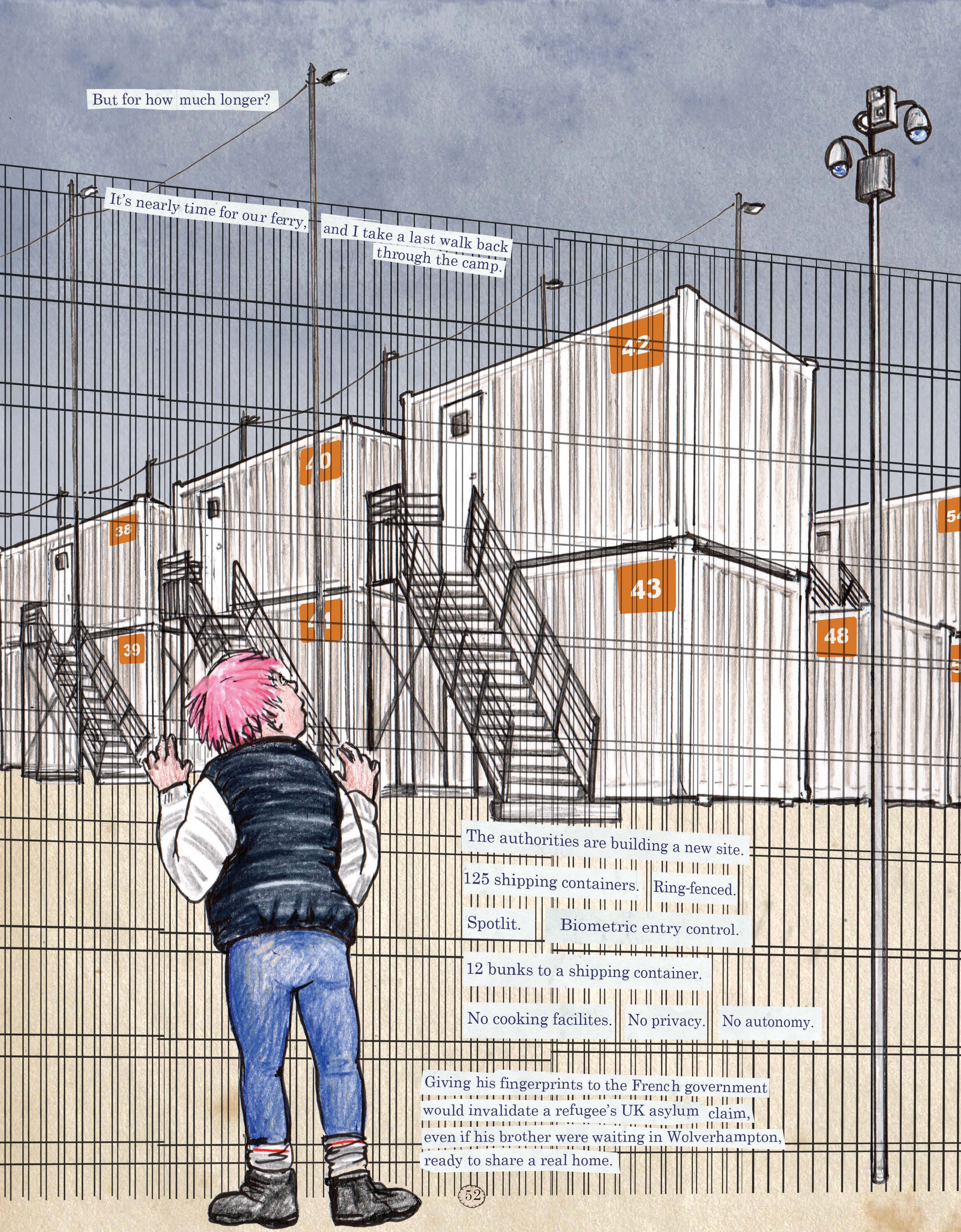

While Evans is her own recurrent character, instantly identifiable by her cartoonishly purple hair, she focuses heavily on individuals living in the camps. She titles her sixth chapter after Hoyshar, an Iraqi father separated from his family and living with a friend in a seven-by-eight-foot shack on the outskirts of the Jungle. He makes Evans and her two fellow volunteers lunch in his “eighteen-inch kitchen,” and soon Evans is drawing her “Fairytale” of smuggling him across the channel to a waiting uncle. Instead they leave Hoyshar facing eviction because the replacement camp of shipping containers will be too small to house everyone after the Jungle is bulldozed. Instead of private family housing, each unit will hold twelve bunk beds and no individual cooking or personal spaces.

The little Kurdish girl Evser is even more affecting. Evans introduces her kicking a soccer ball and then drifting to sleep on Evans’ laps as the small group of volunteers sits with Evser’s family around a cooking fire outside their newly assembled family shack. When police evict Evser’s and neighboring families, they are trucked to Dunkirk where Evans finds Evser sloshing rain-soaked through puddles: “Her mother would dearly love to invite us in and offer us tea, but she lives in a mouldy pit, a hole—it doesn’t qualify as a hovel.” But Evser is smiling again and riding a bike in a concluding two-page spread, after Dunkirk has erected a new camp of “private family huts” and “well-stocked communal kitchens.”

Though the details Evans documents are all true, she acknowledges that to “protect some of the people described in this book their identities have been altered and some characters have been conflated.” It would be disappointing if Hoyshar or Evsar were composite characters, but Evans alters facts out of necessity. If refugees are registered or photographed while in France, the UK bars their entry. In the book’s most disturbing account, a team of police in riot-gear burst into a pregnant woman’s tent, strike her repeatedly in the face and hold her and her crying children’s faces steady in their black gloves as each is photographed and the photographs labeled. It is startling evidence of the power of images—not simply Evans’ but the legal documents that determine the futures of the individuals they depict.

Before a fellow volunteer recounts the event, she says, “I’m going to tell you something and I want it to remain confidential.” Evans answers, “I won’t draw a cartoon about it, I promise,” and then proceeds to present her five-page sequence. Though I presume Evans altered the names and appearances of the family members when she imagined the police photographs, much of her volunteering involved faithful renderings of other refugees. She carried hard-drying watercolors and plastic-sealed paper with her: “what can I give someone who has very little and is about to lose even that? I can give them a piece of paper with their portrait on.”

Before giving those portraits away, she photographed each to include in the narrative of her making them, juxtaposing digital versions of the originals with her later cartoon renderings of the same individuals. The effect is most paradoxical as she describes the intimacy of drawing someone’s face, including one sitter’s “impossibly thick eyelashes” and the “soft, downy hair growing on the upper lip.” As she narrates, she draws her pen drawing the lines of each feature—though when the pen is absent, it is impossible to determine if the image is a representation of a sitter or a representation of her portrait of that sitter.

That peculiar merging of subject and depiction is at the heart of Threads and the genre of comics journalism in general. Despite the real-world seriousness of her subject matter, Evans works in a style associated with traditional newspaper comic strips named “comics” for their humorous content—as when Evans draws herself pushing an impossibly heaped grocery cart of camp supplies. When she includes an actual photograph of a garbage heap in Dunkirk, “a view from the nauseous woman’s tent,” she reminds readers that the book’s other images are recollected interpretations drawn after she returned home. She also implies that a drawing of the garbage wouldn’t adequately convey its reality. While engagingly expressive, her drawings are also gently distancing, dampening the immediacy of the actual camps. The comic doesn’t take readers to Calais and Dunkirk, but to counterparts in a colored-pencil universe. When her cartoon self yells at a border guard, “IT’S NOT A STORY!!! THIS IS REALITY!!!!”, Evans might be yelling at her readers too.

But if her portraits of rightwing politicians Marine La Pen and Theresa May are intentionally warped caricatures, Evans grounds her book in our reality by including actual and far more grotesque statements from other anti-immigrant sources. Framed by a cellphone panel at the end of the first chapter, the first unnamed voice critiques Evans directly: “This cartoon could not be better propaganda for battlefield veteran Islamic militant males invading Northern Europe if Lenin himself produced it.” She includes more social media excerpts between later chapters, until they culminate in a spread of counter arguments literally scissored from newspaper articles and collaged across the two image-less pages.

The style explains Evans’ approach to panel captions throughout. Her narration appears as strips of words layered overtop the artwork, subtly evoking a ransom note culled from newspaper articles. The addition of the physical words over images that take place in a constantly unfolding present moment suits the nature of retroactive narration. Speech in contrast is hand-lettered as part of the art and so part of those present moments, with no speech bubbles, only free-floating words linked to characters by single-line tails (a style long familiar to Doonesbury readers). When characters speak Arabic, Evans accordingly draws their words in Arabic letters, with translations provided by English speakers in the scene or not at all.

She further grounds the physicality of her book through an inventive use of gutters. Instead of traditional empty spaces created by panel frames, her gutters are strips of white lace photographed and digitally manipulated. These titular “threads” reference the lace-manufacturing industry of historic Calais explained on the first page with an image of period-dressed women weaving the “steel lacework” walling in contemporary Calais’ highway. On the final page, Evans draws similar women cutting blocks of lace into bricks and stacking them into a new and higher wall around the port. The visual metaphor bookends the narrative well, emphasizing the power of comics journalism to not simply depict but to interpretively transform.

[The original version of this and my other recent comics reviews appear in the comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Kate Evans, Threads from the Refugee Crisis Kate Evans

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

20/11/17 What is “Literary” Fiction?

My last posts focused on the false division between science fiction and literary fiction, arguing that the two are often best when combined. If you don’t believe me, read Emily St. John Mandel. The author visited my creative writing class last week and read excerpts from Station Eleven to a packed auditorium. She said when she started out a decade ago, many editors rejected her first novel because it combined literary and genre fiction–she was all about crime back then. Now publishers love those combinations: literary mystery, literary scifi, literary fantasy, literary romance.

The genre half of those phrases are fairly straight forward, but what exactly is “literary”?

It’s a tough term to define, especially after decades of misuse. Some still confine it to “narrative realism,” meaning stories that appear to take place in what appears to be our own world. Literary fiction certainly includes those stories, but it also includes stories set in other kinds of worlds. The question is how to get to a “literary” world? I need to steer my creative writing students down some clear paths. Those paths have a tendency to change every century or so, so it’s usually a good idea to include “contemporary” in any definition too.

Ultimately I don’t care where a story takes place–especially since all stories take place in fictional worlds, whether they superficially resemble ours or not. So rather than where, or even what (those fictional worlds can be peopled by gangsters or androids or talking hamster, it makes no difference to me), I just want to know how the story is told. That’s where “literary” resides.

But that’s still pretty vague, so I’ve been searching for fuller definitions. John Gardner, for example, sets five standards for good art in On Becoming an Artist:

- Create a vivid and continuous dream;

- Demonstrate authorial generosity;

- Reveal intellectual and emotional significance;

- Be rendered with elegance and efficiency; and

- Exhibit an element of strangeness.

That’s not bad. Though when I’ve used it with my classes, I’ve had to admit that I have no idea what number 2 means. Kurt Vonnegut, in his book Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction, lists eight rules for writing a short story:

- Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

- Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

- Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

- Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action.

- Start as close to the end as possible.

- Be a Sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

- Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

- Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To hell with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

Also not bad. Though I wouldn’t trust cockroaches to be your editor. The moment you communicate complete understanding to your reader, that’s called the last paragraph. Doesn’t matter if it’s also the first paragraph, or if you’re half way through your meticulously crafted plot outline–stop writing and let that projected ending resonate in your reader’s brain.

But I’m still not satisfied. So I’m drawing from nine more writers–including a playwright, a painter, and two cognitive psychologists–to round out the list. The quotes are there’s, but the six categories are mine:

Psychological realism

David Corner Kidd and Emanuele Castano: “Just as in real life, the worlds of literary fiction are replete with complicated individuals whose inner lives are rarely easily discerned and warrant exploration.”

Inference

Hemingway: “If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.”

Sensory imagery

Anton Chekhov: “Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.”

William Carlos Williams: “No ideas but in things.”

Selection

Georgia O’Keeffe: “Nothing is less than real than realism. Details are confusing. It is only by selection that we get at the real meaning of things.”

Structural coherence

Anton Chekhov: “If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.”

Edgar Allan Poe: “In the whole composition there should be no word written, of which the tendency, direct or indirect, is not to the one pre-established design.”

Stephen King: “When you rewrite, your main job is taking out all these things that are not the story.”

Precision

Strunk and White: “Omit needless words.”

Stephen King: “2nd Draft = 1st Draft – 10%”

Vladimir Nabokov: “My pencils outlast their erasers.”

I don’t think the list is quite done–Gardner’s “strangeness” is missing, but I don’t quite know how to articulate what exactly that means yet (which might be the point).

Artist Richard Prince called art “a revolution that makes people feel good,” which seems important too, though so is curator Robert Storr’s counterpoint: “Good art makes you give something up.”

And are those both the same as Barbara Kruger’s definition: “art is the ability to show and tell what it means to be alive”?

But I may have to give Linda Weintraub the last word: “If art doesn’t sensitize us to something in the world, clarify our perceptions, make us aware of the decisions we have made, it’s entertainment.”

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

13/11/17 Science Fiction Makes You Stupid, part 2

Two weeks ago I posted an excerpt of my essay “The Genre Effect: A Science Fiction (vs. Realism) Manipulation Decreases Inference Effort, Reading Comprehension, and Perceptions of Literary Merit,” which I co-wrote with cognitive psychologist Dan Johnson and is newly published by the journal Scientific Study of Literature. I titled the post “Science Fiction Makes You Stupid,” but a more accurate title would have been: “Readers Who Are Stupid Enough to be Biased Against Science Fiction Read Science Fiction Stupidly.”

I wasn’t expecting the post to draw attention beyond my usual readers, but it quickly became the third most viewed in this blog’s six-year history. I responded to a range of excellent comments last week, and, to continue that conversation, I am including below the four texts that Dan and I used in the experiment. Since they aren’t included in the actual journal publication, I can post them here unabridged.

The conclusions that Dan and I draw refer specifically to these texts and so only tentatively to the larger genres of science fiction and narrative realism, which are each vast and diverse. We needed short passages, no more than 1,000 words each, and so the texts are also necessarily flash fiction. We had originally tried to alter actual published stories, but that produced too many variables. At the sentence level, our two texts vary only according to setting-revealing words and phrases, which then produce two drastically different story worlds, one set in a contemporary small town, another in a futuristic space station. That means any generalizations we suggest about the larger genres are limited to setting-based definitions. While narrative realism may include a lot of things, it typically includes a contemporary, seemingly real-world setting. But science fiction is trickier. Only a subset includes a futuristic, other-worldly setting, so our study is limited to that subset.

By some definitions of science fiction, setting isn’t sufficient, since it is only a surface element. I tend to agree, though I still consider space westerns a form of science fiction. But the setting variations in the two experimental texts can produce more than just surface differences. When I tried a mini-version of the experiment unofficially with one of my advanced creative writing classes, one student inferred deeper levels of significance from the setting details, saying: “The main character feels a tension with humanity and artificial life; feels conflicted about the technological changes around him, the role that pain and messiness play in this structured, manipulated world.” No one described the setting of the narrative realism version as having as much significance.

The question of quality might come in too, since setting-defined science fiction, while still a subset of science fiction, might indicate a lower level of merit. Personally, I consider both texts to be at best mediocre. I wrote them solely for the purpose of experimental manipulation. I’ve published about four dozen short stories in literary journals, including one anthologized in Best American Fantasy, but I would never submit these texts anywhere, regardless of genre.

Finally, I’m including below the two additional texts that feature what Dan and I termed “theory-of-mind explanations.” These are topic-sentence-like statements usually at the beginning of paragraphs that declare overtly what characters are thinking and feeling. According to another study’s definition, “literary” fiction promotes theory-of-mind inferences, and so, we hypothesized, these statements should lower that inferencing and so also lower impressions of “literary” merit. That’s not what happened, which we discuss in the study.

For now, here are the four texts:

TEXT 1: “Narrative Realism”

Jim takes a deep breath, bracing himself before pushing open the glass door. Mrs. Moyers glances at him once and then drops her eyes to her menu, which she continues reading with improbable intensity as Jim walks past her booth. Sally—a woman Jim dated back in high school—squeaks the heel of her sneaker as she pivots and vanishes into the shadows of the kitchen. An older waitress Jim doesn’t know by name eventually plods over to his table, slaps a menu on his placemat without a word or glance, and then continues to the next booth where she chats and giggles a full minute before taking orders.

Jim’s letter to the editor appeared that morning. It isn’t a long piece, barely a half column, a fraction of the other Braxton Herald opinion page contributors. He was awake in bed just a few hours ago, staring at the shadows of his ceiling slowly ebbing to pink, when the delivery kid’s bicycle rattled onto the gravel of his driveway. The paper thunked against the screen door and skidded to the porch step where Jim leaned to pluck it up minutes later. There was no going back to sleep.

He reread the letter under the glare of the kitchen light with the coffee machine hissing behind him. The words looked so official, the font so formal, nothing like the sheet of hand-written stationary he’d slapped into an envelope the week before. His hand had cramped from gripping the pen so hard, each letter gouged into the yellow of the paper. He’d ripped up the first two drafts, scattering their fluttery shreds across the kitchen tiles after he missed the wastebasket both times. If only he’d flung the pen in too, kicked the metal can skidding across the carpet.

He didn’t skim to the bottom paragraph before crumpling his Herald into a jagged ball and shoving it into the same can. Now another copy sprawls across the unbussed table beside him, a smear of ketchup bloodying the masthead. That may be another jutting from Mrs. Moyers’ open purse, the pages rerolled into a tight cylinder like a weapon. When the waitress finally returns, she frowns down at him, sharpened pencil tip stabbing tiny wounds into her order pad.

“So,” she says, “find anything you like? Or is our selection too small for you?”

Jim feels his lip quiver as he tries to smile. “It all looks good to me.”His voice is wavering too. “But I think I’ll just have my usual. A cheeseburger.”

She slashes a few marks across the pad in her palm, her eyes still on Jim. “Sure that’s not too”—she pauses before puffing her voice into a posh accent: “Par-o-ch-i-al for you?”

Jim’s face is heating up now. “Well now,” he says, “where’d you go and learn a big word like that?” His laugh is sharp. He leans back, letting his arms settle across the booth back. The metal is cool but comfortable, just the right height. “Did you sound it out all by yourself?”

The waitress stands open-mouthed, eyes round, before retreating, her heels echoing against the tiled floor. Mrs. Moyers is suddenly standing and fishing bills from her purse. Sally—he didn’t notice her slinking back from the kitchen before—is drifting further down the counter, neck rigid as if afraid she might glance over by accident. He’d never said a mean word to her the whole semester they’d dated. But that was quite a few years and Herald editions ago.

Jim glances at the neighboring table again. The puddle of ketchup has expanded into the headline. The paper is ruined. Even if he jumped up and started mopping the pages, he couldn’t repair the damage. He kicks his boots up on the booth seat opposite him instead. His soles might leave a dirt smear, but nobody else will be sitting there anytime soon.

He smooths his hand across the wrinkles of his placemat, remembering how good it felt writing that letter. When Sally broke up with him senior year, he didn’t go and hunt down that runt of a junior she’d fallen for in her stupid Ceramics class. He didn’t jab the kid in the face till his bones of Jim’s fists throbbed and the calloused skin was wet with the other kid’s blood. Just yesterday his jerk of a neighbor let her poodle crap in his lawn again, not ten minutes after Jim had mown it, the air still thick with the scent of cuttings. But Jim didn’t yell at her, didn’t shout in her wrinkled face till his throat was raw.

Jim arranges his fork and knife along the edges of the placemat now, gets everything flush and straight, the fluorescent lights in the polished metal. His meal will be here soon enough.

TEXT 2: “Science Fiction”

Corporal Jones takes a deep breath, bracing himself before stepping through the airlock. Engineer Grady glances at him once and then drops her eyes to her mobile screen, which she continues reading with improbable intensity as Jones walks past her booth. Sally—a four-armed Alpha-Centarian Jones dated back at the Academy—squeaks the heel of her anti-gravity boot as she pivots and vanishes into the shadows of the galley. An ensign on server duty who Jim doesn’t know by name eventually plods over to his table, grudgingly projects a holographic menu over his placemat without a word or glance, and then continues to the next booth where she chats and giggles a full minute before taking orders.

Jones’ message to Command appeared that morning. It isn’t a long piece, barely a full screen, a fraction of the other Colony Morale Survey respondents. He was awake in his bunk just a few hours ago, staring at the gray of his sky-replicating ceiling slowly ebbing to pink, when the satellite dish mounted above his quarters started grinding into position to receive the day’s messages relayed from Earth. The download light on his mobile screen plinked as Jim logged on seconds later. There was no going back to sleep.

He reread it under the glare of his desk light with the air duct hissing behind him. The words looked so official, the font so formal, nothing like the electronic form he’d filled out by hand before slapping the SEND key the week before. His hand had cramped from gripping the stylus so hard, each letter denting the glow of the screen. He’d deleted the first two drafts, dragging their blinking icons to the cartoon wastebasket in the screen corner. If only he could have flung the stylus in too, kicked a real metal can skidding across the floor.

He didn’t skim to the bottom paragraph before stabbing the CLOSE button and dragging the Survey to the same wastebasket icon. Now another Survey copy blinks from the unbussed table beside him, a smear of ketchup bloodying the table’s built-in screen. That may be another Survey glowing from Grady’s screen, the pages as bright as an exploding plasma grenade.

When the ensign finally returns, she frowns down at him, steely stylus tip stabbing tiny wounds into her order screen. “So,” she says, “find anything you like? Or is our selection too small for you?”

Jim feels his lip quiver as he tries to smile. “It all looks good to me.” His voice is wavering too. “But I think I’ll just have my usual. A cheeseburger.”

She slashes a few marks across the screen in her palm, her eyes still on Jim. “Sure that’s not too”—she pauses before puffing her voice into a posh accent: “Par-o-ch-i-al for you?”

Jim’s face is heating up now too. “Well now,” he says, “where’d you go and learn a big word like that?” His laugh is sharp. He leans back, letting his arms settle across the booth back. The metal is cool but comfortable, just the right height. “Did you sound it out all by yourself?”

The ensign stands open-mouthed, eyes round, before retreating, her boots echoing against the metal floor. Grady is suddenly standing and fishing mess hall tokens from her beltpack. Sally—he didn’t notice her slinking back from the kitchen before—is drifting further down the counter, neck rigid as if afraid she might glance over by accident. He’d never said a mean word to her the whole semester they’d dated. But that was quite a few years and Command Surveys ago.

Jim glances at the neighboring table again. The puddle of ketchup has seeped into a crack in the screen. The viewer is ruined. Even if he jumped up and started mopping the table, he couldn’t repair the damage. He kicks his boots up on the booth seat opposite him instead. His soles might leave a smear, but nobody else will be sitting there anytime soon.

He smooths his hand across the computer-generated wrinkles of his holographic placemat, remembering how good it felt writing how he felt for once. When Sally broke up with him, he didn’t go and hunt down that runt of an android she’d fallen for in her stupid Programming class. He didn’t jab the ugly droid in the face till the bones of Jim’s fists throbbed and the calloused skin was wet with synthetic blood. Just yesterday his jerk of a bunkmate let his pet space squid crap on his desk again, not ten minutes after Jim had cleaned it, the air still thick with the scent of ammonia. But Jim didn’t yell at him, didn’t shout in his wrinkled face till his throat was raw.

Jim arranges his fork and knife along the edges of the placemat now, gets everything flush and straight, the fluorescent lights in the polished metal. His meal will be here soon enough.

TEXT 3: “Narrative Realism with Theory-of-Mind Explanations”

Jim knows everyone in the diner will be angry at him. He takes a deep breath, bracing himself before pushing open the glass door. Mrs. Moyers glances at him once and then drops her eyes to her menu, which she continues reading with improbable intensity as Jim walks past her booth. Sally—a woman Jim dated back in high school—squeaks the heel of her sneaker as she pivots and vanishes into the shadows of the kitchen. An older waitress Jim doesn’t know by name eventually plods over to his table, slaps a menu on his placemat without a word or glance, and then continues to the next booth where she chats and giggles a full minute before taking orders.

He knows why they’re mad. They consider him a traitor for insulting the town in their local newspaper. He called them all “parochial” and “small minded.” Jim’s letter to the editor appeared that morning. It isn’t a long piece, barely a half column, a fraction of the other Braxton Herald opinion page contributors. He was awake in bed just a few hours ago, staring at the shadows of his ceiling slowly ebbing to pink, when the delivery kid’s bicycle rattled onto the gravel of his driveway. The paper thunked against the screen door and skidded to the porch step where Jim leaned to pluck it up minutes later. He was too anxious. There was no going back to sleep.

He regretted writing the letter even before he reread it under the glare of the kitchen light with the coffee machine hissing behind him. The words looked so official, the font so formal, nothing like the sheet of hand-written stationary he’d slapped into an envelope the week before.

He’d been angry when he wrote it. His hand had cramped from gripping the pen so hard, each letter gouged into the yellow of the paper. He’d ripped up the first two drafts, scattering their fluttery shreds across the kitchen tiles after he missed the wastebasket both times. If only he’d flung the pen in too, kicked the metal can skidding across the carpet.

He wishes he’d never written the letter, but it’s too late; everyone’s seen it. He didn’t skim to the bottom paragraph before crumpling his Herald into a jagged ball and shoving it into the same can.

Now another copy sprawls across the unbussed table beside him. It’s as if they’re all thinking about killing him, the way a smear of ketchup is bloodying the masthead. That may be another jutting from Mrs. Moyers’ open purse, the pages rerolled into a tight cylinder like a weapon.

When the waitress finally returns, she frowns down at him, sharpened pencil tip stabbing tiny wounds into her order pad. “So,” she says, “find anything you like?” Then she quotes a word from his letter, in case there is any doubt she read it. “Or is our selection too small for you?”

Jim tries to be friendly, but he’s still nervous. His lip quivers as he tries to smile. “It all looks good to me.”His voice is wavering too. “But I think I’ll just have my usual. A cheeseburger.”

She slashes a few marks across the pad in her palm, her eyes still on Jim. “Sure that’s not too”—she pauses before puffing her voice into a posh accent, using another word from his letter: “Par-o-ch-i-al for you?”

Jim’s face is heating up now too, but not with embarrassment. He’s getting angry. “Well now,” he says, “where’d you go and learn a big word like that?”His laugh is sharp. Anger makes him confident. He leans back, letting his arms settle across the booth back. The metal is cool but comfortable, just the right height. “Did you sound it out all by yourself?”

The waitress is shocked. She stands open-mouthed, eyes round, before retreating, her heels echoing against the tiled floor.

Others heard his comment, and that makes them fear what he might say to them if given the chance. Mrs. Moyers is suddenly standing and fishing bills from her purse. Sally—he didn’t notice her slinking back from the kitchen before—is drifting further down the counter, neck rigid as if afraid she might glance over by accident. He’d never said a mean word to her the whole semester they’d dated. But that was quite a few years and Herald editions ago.

His friendships with everyone in Braxton are ruined. He just has to accept that he’s friendless now. Jim glances at the neighboring table again. The puddle of ketchup has expanded into the headline. The paper is ruined too. Even if he jumped up and started mopping the pages, he couldn’t repair the damage. He kicks his boots up on the booth seat opposite him instead. His soles might leave a dirt smear, but nobody else will be sitting there anytime soon.

Maybe writing that letter wasn’t such a bad idea. He’d spent too much of his life not letting himself get angry. He smooths his hand across the wrinkles of his placemat, remembering how good it felt writing how he felt for once. When Sally broke up with him senior year, he didn’t go and hunt down that runt of a junior she’d fallen for in her stupid Ceramics class. He didn’t jab the kid in the face till his bones of Jim’s fists throbbed and the calloused skin was wet with the other kid’s blood. Just yesterday his jerk of a neighbor let her poodle crap in his lawn again, not ten minutes after Jim had mown it, the air still thick with the scent of cuttings. But Jim didn’t yell at her, didn’t shout in her wrinkled face till his throat was raw.

At least now things are the way they should be. Jim arranges his fork and knife along the edges of the placemat now, gets everything flush and straight, the fluorescent lights in the polished metal. His meal will be here soon enough.

TEXT 4: “Science Fiction with Theory-of-Mind Explanations”

Corporal Jones knows everyone in the space station mess hall will be angry at him. He takes a deep breath, bracing himself before stepping through the airlock. Engineer Grady glances at him once and then drops her eyes to her mobile screen, which she continues reading with improbable intensity as Jones walks past her booth. Sally—a four-armed Alpha-Centarian Jones dated back at the Academy—squeaks the heel of her anti-gravity boot as she pivots and vanishes into the shadows of the galley. An ensign on server duty who Jim doesn’t know by name eventually plods over to his table, grudgingly projects a holographic menu over his placemat without a word or glance, and then continues to the next booth where she chats and giggles a full minute before taking orders.

He knows why they’re mad. He called the crew “parochial” and “small minded.” They consider him a traitor for insulting the base in an official report. Jones’ message to Command appeared that morning. It isn’t a long piece, barely a full screen, a fraction of the other Colony Morale Survey respondents. He was awake in his bunk just a few hours ago, staring at the gray of his sky-replicating ceiling slowly ebbing to pink, when the satellite dish mounted above his quarters started grinding into position to receive the day’s messages relayed from Earth. The download light on his mobile screen plinked as Jim logged on seconds later. He was too anxious. There was no going back to sleep.

He regretted writing the report even before he reread it under the glare of his desk light with the air duct hissing behind him. The words looked so official, the font so formal, nothing like the electronic form he’d filled out by hand before slapping the SEND key the week before. He’d been angry when he wrote it. His hand had cramped from gripping the stylus so hard, each letter denting the glow of the screen. He’d deleted the first two drafts, dragging their blinking icons to the cartoon wastebasket in the screen corner. If only he could have flung the stylus in too, kicked a real metal can skidding across the floor.

He wishes he’d never answered the questionnaire, but it’s too late; everyone’s seen it. He didn’t skim to the bottom paragraph before stabbing CLOSE button and dragging the Survey to the same wastebasket icon. Now another Survey copy blinks from the unbussed table beside him. It’s as if that report will get him killed, the way a smear of ketchup is bloodying the table’s built-in screen. That may be another Survey glowing from Grady’s screen, the pages as bright as an exploding plasma grenade.

When the ensign finally returns, she frowns down at him, steely stylus tip stabbing tiny wounds into her order screen. “So,” she says, “find anything you like?” Then she quotes a word from his report, in case there was any doubt she read it. “Or is our selection too small for you?”

He’s trying to be friendly, but he’s still nervous. Jim’s lip quiver as he tries to smile. “It all looks good to me.” His voice is wavering too. “But I think I’ll just have my usual. A cheeseburger.”

She slashes a few marks across the screen in her palm, her eyes still on Jim. “Sure that’s not too”—she pauses before puffing her voice into a posh accent, using another world from his report: “Par-o-ch-i-al for you?”

Jim’s face is heating up now too, but not with embarrassment. He’s getting angry.“Well now,” he says, “where’d you go and learn a big word like that?” Anger makes him confident. His laugh is sharp. He leans back, letting his arms settle across the booth back. The metal is cool but comfortable, just the right height. “Did you sound it out all by yourself?”

The ensign is shocked. She stands open-mouthed, eyes round, before retreating, her boots echoing against the metal floor. Others heard his comment, and that makes them fear what he might say to them if given the chance. Grady is suddenly standing and fishing mess hall tokens from her beltpack. Sally—he didn’t notice her slinking back from the galley before—is drifting further down the counter, neck rigid as if afraid she might glance over by accident. He’d never said a mean word to her the whole semester they’d dated. But that was quite a few years and Command Surveys ago.

His relationships with everyone in the base are ruined. He just has to accept that he’s friendless now. Jim glances at the neighboring table again. The puddle of ketchup has seeped into a crack in the screen. The viewer is ruined too. Even if he jumped up and started mopping the table, he couldn’t repair the damage. He kicks his boots up on the booth seat opposite him instead. His soles might leave a smear, but nobody else will be sitting there anytime soon.

Maybe writing that report wasn’t such a bad idea. He’d spent too much of his life not letting himself get angry. He smooths his hand across the computer-generated wrinkles of his holographic placemat, remembering how good it felt writing how he felt for once. When Sally broke up with him, he didn’t go and hunt down that runt of an android she’d fallen for in her stupid Programming class. He didn’t jab the ugly droid in the face till his bones of Jim’s fists throbbed and the calloused skin was wet with synthetic blood. Just yesterday his jerk of a bunkmate let his pet space squid crap on his desk again, not ten minutes after Jim had cleaned it, the air still thick with the scent of ammonia. But Jim didn’t yell at him, didn’t shout in his wrinkled face till his throat was raw.

At least now things are the way they should be. Jim arranges his fork and knife along the edges of the placemat now, gets everything flush and straight, the fluorescent lights in the polished metal. His meal will be here soon enough.

- 13 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

06/11/17 America’s Worst Moments

Here’s my favorite worst review:

“Another sign of the madness in Gavaler’s method is that he drags America’s worst moments into the discussion. Like historians James Loewen (Lies My Teacher Told Me, 1995) and Howard Zinn (A People’s History of the United States, 1995), he really wants his undergrads to go home for Thanksgiving and tell their parents that this country is just one big Indian Burial Ground. His obsession with the Ku Klux Klan is extraordinarily tedious.”

That’s blogger Justine Hickey panning my first book, On the Origin of Superheroes, back in 2015. Though I was delighted to be clumped with the likes of Zinn and Loewen, I thought my focus on the KKK was a bit brief. If you really want “extraordinarily tedious,” you need to look at my new book Superhero Comics out last month from Bloomsbury. Rather a than the few “glancing, pandering passages,” the Klan gets a full, roughly 10,000-word chapter. An earlier version was published by the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics in 2013. The editors at Routledge liked it enough to include it as the opening chapter of the 2015 collection Superheroes and Identities. The editors at Literary Hub liked the new version enough to feature an excerpt last Friday:

How the KKK Shaped Modern Comic Book Superheroes:

Masked Men Who Take the Law into their own Hands

Bloomsbury also contacted me last week to say that a Turkish publisher wants to publish a translation. The opening round of reviews on Net Gallery and Amazon have all been 4 and 5 stars too. The harshest reviewer called Superhero Comics “very academic,” though another said it was “accessible for any reader.” Blogger Bill Capossere said it “aims for the sweet spot between the academic and the lay reader” and so “is a thoughtful, well researched academic work that is highly accessible.” As far as my KKK obsession, Capossere writes:

“While most people may be familiar with the controversy over the superhero as vigilante, Chapter Three went down (for me, at least) an unexpected path, with a long, detailed exploration of the superhero story’s connection to the Ku Klux Klan. At first blush this may seem a stretch (and admittedly, at times, perhaps at second blush as well), but Gavaler makes a thoughtful, supported case for it… when Gavaler stretches (I think) a point, instead of “Oh, c’mon,” I find myself backtracking, rereading some of what led to the point, and thinking more critically of my own stance, even if I eventually stick with my original view. In other words, Superhero Comics doesn’t simply inform but makes one think, even about topics one is generally familiar with. Which is why it’s highly recommended, as was his first book, On the Origin of Superheroes, and why I’ll be picking up his next book on comics as well.”

When the Klan showed up at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in August, Superhero Comics was already heading to the printer. I wasn’t expecting my analysis of early 20th century white supremacy to be timely. Here’s a quick history lesson:

The statue of Robert E. Lee, the literal focal point of the rally, was commissioned in 1917, during the rise of the second KKK and the white supremacist movement of eugenics across the U.S. Although the Klan is most often recalled as a terrorist organization limited to the South during the Reconstruction period, it was reformed nationally in 1915 after the widely acclaimed blockbuster film The Birth of a Nation adapted the 1905 novel The Clansman, a melodramatic best-seller that portrayed the KKK as the righteous and heroic protectors of the South from the villainy of “Negro Rule.” This was a standard interpretation of history during the first decades of the 20th century. Staunton-born President Woodrow Wilson was one of the majority of Americans who agreed. After a special screening of The Birth of a Nation in the White House, Wilson commented: “it is all so terribly true.”

When the Lee statue was finally erected in 1924, the KKK controlled a majority of delegates in the Democratic National Convention. The Convention was held in New York city that year, and after the party defeated a platform resolution that would have condemned Klan violence, thousands of KKK members, including Convention delegates, held a celebratory rally in New Jersey. The following year, 30,000 Klan members marched in full regalia in Washington DC. National membership was estimated well over three million.

The popularity of the Klan reflected the wider white nationalism of eugenics, which in the pre-DNA science of genetics argued for the hereditary superiority of northern Europeans. Following the advice of the Carnegie Institute, the Rockefeller Foundation, and other eugenics advocates, federal and state governments attempted to protect white bloodlines through immigration restrictions, racial segregation, anti-interracial marriage laws, and forced sterilization. Madison Grant’s white supremacist treatise The Passing of the Great Race became a national best-seller in 1916, calling for the sterilization of “worthless race types.” President Theodore Roosevelt and Adolf Hitler both praised the book. Hitler also said Germany needed to model itself on the U.S., especially California and Virginia, the leading states in the eugenics movement.

I told my Superheroes class that on the first day of this semester because it’s the cultural and political context that led to costumed superheroes in comics. That’s not a condemnation of superheroes or of America. It’s just a historical fact, one we need to keep in focus in today’s cultural and political context too. Not all of America’s worst moments are in its past.

Tags: charlottesville, Kkk, Superhero comics

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized