Monthly Archives: March 2021

29/03/21 Yet Another Reason Why I’m not Andy Warhol

It seems other people have saner hobbies than I do. Instead of picking up a crossword puzzle or a novel when I have a down moment or an urge to mentally recharge, I copy and paste photos into Word Paint and fiddle with them until they don’t look like photos anymore. It’s not the worst habit in the world, but it does feel a little obsessive. I sometimes tell myself it’s a form of research, which it is: I’m exploring the edges of distortion, looking for the sweet spot where an image teeters between representation and total abstraction. I’m especially interested in how simplification and exaggeration at the micro-level relate to the macro-level image, how a pattern of digital strokes can seem to obliterate all content, and yet roll your chair backwards a yard or two and the ghost of the original photograph is still present as a gestalt effect. Brains are particularly good at piecing together broken shards.

Yesterday I read that an appeals court overruled a lower judge’s decision about whether Andy Warhol broke copyright law when he adapted a photograph of Prince without the photographer’s permission. The question is over whether Warhol’s image adequately transformed its source material. The judge said no:

“The Prince Series retains the essential elements of its source material, and Warhol’s modifications serve chiefly to magnify some elements of that material and minimize others. While the cumulative effect of those alterations may change the Goldsmith Photograph in ways that give a different impression of its subject, the Goldsmith Photograph remains the recognizable foundation upon which the Prince Series is built.”

I think “minimizing” and “magnifying” occur in relation to each other and both are aspects of simplification. More specifically, “magnifying” something is an inevitable effect produced by minimizing other things. Warhol simplified the photograph by cropping it and reducing details in the cropped area. He also added contour lines and opaque color.

The first judge ruled in favor of Warhol in 2019, placing his modification within the range of fair use:

“The Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure. The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone. Moreover, each Prince series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince — in the same way that Warhol’s famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as ‘Warhols,’ not as realistic photographs of those persons.”

The 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals strongly disagrees:

“We conclude that the district court erred in its assessment and application of the fair-use factors and that the works in question do not qualify as fair use as a matter of law… We feel compelled to clarify that it is entirely irrelevant to this analysis that “each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol.'” Entertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labors of others.”

Arguably, Warhol IS a “celebrity-plagiarist,” since his Monroe series were taken from a publicity movie still and so are vulnerable to the same 2nd Circuit conclusion. I have mixed feelings about both decisions (neither seems quite right to me). Either way, I’m really hoping the Vice-President and/or her photographers won’t be suing me any time soon (I featured a Harris series here in January). I also won’t be suing myself. Some of my more recent transformative adaptations are of a considerably less iconic and larger-than-life figure: me.

I’ll leave others to judge whether and in what sense these are or are not immediately recognizable as Gavalers.

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

22/03/21 Reappearance of Argentina’s Disappeared

From 1976 to 1983, the U.S. backed a brutal, anti-communist coup and dictatorship in Argentina that disappeared thousands of so-called subversives in the name of preserving social order. Perramus was conceived in the regime’s penultimate year and published in Europe the year after its collapse. The novel’s title character—an amnesiac who assumes the name of the clothing manufacturer he finds on the label inside his borrowed coat—embodies the psychic toll Argentina suffered. The novel’s absurdist narratives map a parallel universe that reflects the real-world horror of the authors’ home.

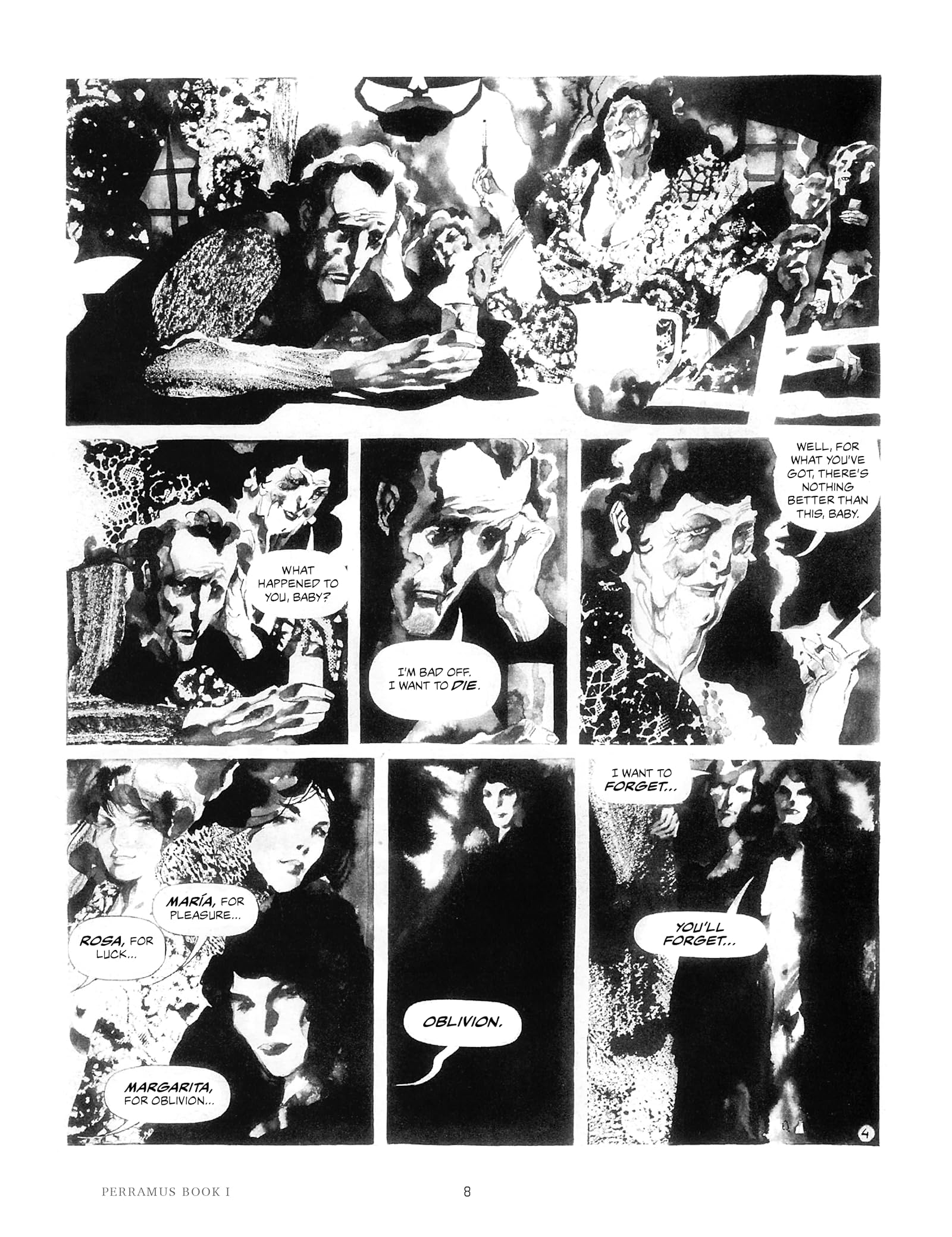

The fabric of that universe is rendered in artist Alberto Breccia’s eclectically surreal and monolithically black-and-white style dominated by painterly brushwork alien to most mainstream U.S. and U.K. comics of the same decade. While conforming to rigid three-row layouts with unframed and uninterrupted gutter edges, the textured interiors of Breccia’s panels are revolutionary in their combination of precision and expressionistic energy. Perramus includes over 460 pages, and literally each offers panel art that could be extracted and framed on a gallery wall. An afterword lists Breccia’s range of materials and techniques (“ink, acrylic, graphite, collage, scraping, staining, dripping, etc.”), but that variety remains unified by his signature line and the printer’s unvarying grayscale. While faces dominate his frames, Breccia imbues buildings and landscapes with equal energy, often pushing toward complete abstraction.

Fans of U.S. comics artist Bill Sienkiewicz should recognize a kindred spirit in the flamboyant vacillations between jagged cartooning and detailed realism. The direction of influence is difficult to determine since the first book of Perramus appeared in 1984, the same year Sienkiewicz departed from his derivative Neal Adams style to produce his ground-breaking New Mutants artwork. Breccia’s subject, matter, however, outstrips the Marvel superhero scripts that curtailed Sienkiewicz. Though Breccia evokes Argentina, the world of his art is its own country, one especially apt for communicating his nation’s political dystopia.

It’s no surprise that the project originated with Breccia, who approached Sasturian, an accomplished writer but one then new to the comics form, to produce a script, which the two revised together. Originally Perramus was an eighty-page graphic novel, divided into eight-page chapters, published serially before collected in a single volume. It grew into four distinct novels of increasing length, the last published in 1989.

Book One depicts an unnamed revolutionary escaping a military raid and then choosing to literally sleep with Oblivion (a kind of mythical goddess). After conscripted by the military to dump disappeared objects at sea (including himself), the renamed Perramus escapes with a sidekick, Canelones, into a sequence of absurdist adventures as he follows the out-of-date guidebook left in his coat pocket by a previous owner. Soon he’s on an island-nation freeing a complacent political enemy and then decoding a Borges sonnet for secret messages. There’s a movie company in there too—one that produces only trailers to scam investors. The effect is eclectic chaos papering over a violently meaningless abyss.

The next three books provide clearer conceits for the nihilistic antics. The second sends the team—Perramus, Canolones, and the Enemy—to protect the six citizens of Santa Maria who secretly possess and safeguard the soul of the city which is in danger of literally vanishing if the authoritarian regime kills them first. The fourth book returns to the island-nation of the first book, where the heroes join forces with a secret circus to combat a capitalist takeover literally fueled by the island’s harvesting of bird shit. The last and longest book is the most light-hearted, written seven years after Argentina’s restoration of democracy. Now employed by real-world novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the heroes must track down the missing smile of the nation’s most beloved actor—or, more literally, purchase the scattered teeth of his disinterred skull.

As much as I admire Breccia’s art and Sasturain’s dystopic narrative scope, their collaboration is marred by a dated misogyny most apparent in a reflexive focus on prostitution. When Perramus escapes the military raid on page one, he travels immediately to a brothel, where he chooses between three sex workers—Pleasure, Luck, and Oblivion. The last also narrates the one-page epilogue, the longest sequence of speech balloons for a female character in the entire collection. The first of Santa Maria’s soul-carriers is the “most famous and cheapest whore in the neighborhood,” who only accepts antique coins from before the dictatorship. The fifth is an elderly Dona Juan who competes on a TV show to complete “six consecutive couplings” with “a minimum of” violence in a half hour. It’s a challenge because each woman is considered so ugly: old, fat, skinny, small, and legless. He is successful until the last, who is unexpectedly beautiful, and when he fails to ejaculate, the crowd roars, “FAGGOT!!!”—unaware that he has fallen in love for the first time in his life.

Perhaps the authors matured a little in the mid-80s, since the last two books are free of prostitutes and overt sex scenes. Canolones does receive a peck on the lips from an Arab woman he saves from white supremacists in Paris. A turbaned friend translates: “She’s very grateful,” and the two literally sail off together in the chapter’s closing panel. After the previous books’ exploitive excesses, the notion that a woman will repay a violent male savior with sex might seem comparatively quaint. The chapter is titled “Coquetry.” The translator, Erica Mena, also assures readers in an ending note that Canolones’ name in the original work, the Black Boy (“el Negrito”), is “completely innocuous and inoffensive” in context.

Although not all of Perramus translates well into our contemporary English context, most of it does. The narrative and visual details are a surrealist kaleidoscope (I didn’t even mention the extended cameos by Frank Sinatra, Fidel Castro, and Ronald Reagan), entertaining on a first viewing and further rewarding on a careful second. I look forward to Fantagraphics’ next publication of Breccia’s seminal works.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

15/03/21 Stop Reading Comics (and start looking at them)

For reasons that annoy me, looking at sequenced images (AKA, comics) is usually called “reading.” While reading is certainly involved when the sequenced images include words, I don’t see why experiencing images in a set order should share a verb with language apprehension. Sure, you can “read” anything in the sense of “interpret.” I’ve told my students to “close read” an image. But that’s not the same thing as: decode the meaning of this set of ordered images as you would decode the meaning of a set of ordered words.

With the exception of some visual art, words are always apprehended in a set order. For images, that order is called “linear.” Words are read in linear order too–but no one bothers stating that because it’s self-evident. And also nearly inevitable. While you could read the words in this paragraph non-lineally (read the first word of each flush-left line, for instance), readers rarely do. That’s because they’re “reading.”

The non-linear relationships between images, however, are more significant on a comics page. If linear order were all that matters, this six-image sequence (of two figures speaking to each other by phone from two phone booths) would always be apprehended as follows:

Those images are based on Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant from the 1963 action-comedy Charade (which is in public domain, and so fair game for my abstract adaptations). When arranged on a page, they produce a 3×2 grid:

That arrangement assumes a z-path viewing path. But the same arrangement viewed as two columns of three images each (instead of as three rows of two panels images each) would produce an n-path and so a different “linear” order:

Transposing that linear order into its own z-path produces this page arrangement:

If words were involved (and so actual “reading”), the sequence order would be set. But since the images are wordless, their order is ambiguous. I’m not even convinced a viewer necessarily begins in the top left corner or ends in the top right corner, though both z-path and n-path dictates it. I suspect viewers approach the wordless page holistically, beginning wherever their eyes are most attracted and roaming in any and multiple direction afterwards. That’s not to say viewers don’t assume the image content is chronological. I suspect they do. But appreciating the temporal relationships of the depicted moments relative to the story world does not require viewing them in that temporal order.

In terms of page space, when the eye travels “up,” viewers know they are moving to images depicting earlier moments, and when the eye travels “down,” viewers know they are moving to images depicting later moments. It’s also possible to experience different temporal relationships (some images might be understood as occurring simultaneously, for instance). But however the images are ordered in the depicted time span of the story world, the order of viewing is independent. Viewers control both pace and direction.

Unless viewers are “reading” the images.

Words can be read in any order too, but their meanings are dependent on their sequence. Reading words backwards (sequence their on dependent are meaning their but) produces meaning only to the degree that you mentally reorder them. That’s not true of images, because an image in isolation produces more meaning than a word in isolation.

You might liken an image to a sentence or paragraph or stanza, but that is misleading too, because it misses the additional meanings produced by non-linear juxtapositions. The difference in effect between these two image arrangements is more than their linear viewing paths:

The first places the two faces in the center squares facing each other. The second reverses their positions so the two faces are facing away from each other:

In terms of the story world, the two characters are never actually facing each other because they are in different locations. The effect is produced through image arrangement, creating a connotation of greater intimacy in the middle row. That’s true of both arrangements, but as the cropped close-ups place the implied viewer into closer proximity, the direction of the figures’ gazes create further connotations. I suspect most viewers would perceive the figures facing toward each other as more emotionally connected to each other, and the facing-away figures as more estranged.

But neither effect occurs when the images are “read” in linear isolation.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

08/03/21 What the Potato Heads Saw on Mulberry Street

Conservative pundit Glenn Beck said last week: “Buy Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head because it’s the end of an era. It is the end of freedom in America.”

Mr. Beck also said: “They are banning Dr. Seuss books. How much more do you need to see before all of America wakes up? This is fascism! We don’t destroy books. What is wrong with us, America?”

Ted Cruz, noting the sudden surge in Dr. Seuss books sales on Amazon, tweeted: “Could Biden try to ban my book next?”

That’s presumably because Fox News implied that Biden was somehow responsible for the Seuss estate’s decision not to print new editions of six books that were already out of print: “Biden erases Dr. Seuss from ‘Read Across America’ proclamation as progressives seek to cancel beloved author.” Fox News also used graphics of popular Dr. Seuss books that were not of the six out-of-print ones, implying that all Seuss books would soon be unavailable.

Facebook memes distorted facts further:

It may seem a little silly to devote political attention to children’s products, but pop culture is pervasive and toys and books influence childhood experience, so it really isn’t so trivial. (Also, I’ve built my academic career on superhero comics, so I can hardly claim to be above the topic.)

So let’s do this one at a time, starting with the potatoes.

First, to clarify what Hasbro did: they added a new toy called “Potato Head,” no “Mr.” or “Mrs.” and so nothing to indicate gender. But they didn’t cancel their pre-existing toys. Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head are still available.

First question: why did Hasbro do this? There was no boycott or petition or anything that I’ve heard about. The news leaked after some internal meeting where the people who run the company initiated the change. I don’t think anyone outside the company knew it was coming. So why add the new toy?

If Hasbro is like all other corporations, they have one primary goal: make as much money as they can for their shareholders. My best guess is that they saw that Mr. and Mrs. weren’t selling well and thought that they could attract progressive parents with a new non-gendered version. But they also kept the old toy, presumably because they thought it would sell better with conservative parents (though I’m a progressive parent who grew up with the Mr. and Mrs. toys and I still happily bought them for my kids).

So what’s wrong with any of that? If you like the traditional toy, great, there it is, go buy it. If you like the non-gendered toy, great, there it is, go buy it. Hasbro is maximizing sales (which is all they care about), but parents are given a greater range of choices. Now if the old toy was eliminated, that would be reason to complain. But it wasn’t. And if you don’t like the new non-gendered version, then you definitely shouldn’t buy it. But why complain that other parents now have the option of buying it? This is how the free market works. Companies make products and compete for buyers. Some products rise and some fall. Where is the problem?

On a personal note, I raised two kids, a girl and a boy. We bought all kinds of toys, traditional “boy” toys, traditional “girl” toys, and non-gendered toys. They each could play with whatever they wanted. And I do remember my toddler daughter being indifferent to the yellow Tonka dump truck (one of my own favorite toys growing up) and then my son really enjoying it a couple years later. That’s great. I didn’t care what they played with. It was sort of the free market approach at the level of our living room.

Now about Dr. Seuss.

I generally object to the term “cancel culture” because it tends to be used exclusively to describe actions by progressives and not to describe similar actions by conservatives, but let’s set the general issue aside and look at this specific incident. The Seuss estate decided to stop publishing six of the author’s most obscure books. They were not responding to any petition or other pressure to do this. The decision was unexpected and came entirely from within their organization.

Jack Shafer, a senior writer at Politico.com (and so a member of the so-called “liberal MSM”), penned a pretty good op-ed on the topic, which I recommend. Shafer comes down pretty hard on the Seuss estate. If you don’t have time to click the link, here are two pertinent passages:

“It’s a little like a prestigious restaurant formally announcing that it’s no longer offering an unpopular dish it hasn’t cooked in several years.” In other words, the books were out of print already, so why make this announcement at all? It seems like an odd kind of publicity stunt. (If the estate is run by evil geniuses, then maybe they were banking on the conservative backlash and misinformation, knowing it would spike sales across all Seuss titles. Seems like a stretch, but who knows.)

Shafer also makes a deeper critique: “Of course, the owners of the Seuss works have every right to do what they please with their property. But if the goal is to better understand the grievous errors we have made in our media depictions of Asian, Black and Arab people, we would be better served by a decision that both acknowledges the racism but doesn’t impede access to the offending material.”

It’s a decent point. I think we once had a copy of And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street somewhere in the house, but I’ve never even glimpsed the other five books. I googled to find the problematic images (and so can confirm that, yes, the characters from “the African island of Yerka” really do look like monkeys), and was intending to copy and paste them here. But now I’m finding that I don’t want to. I apparently agree with Shafer that access shouldn’t be impeded (feel free to google them yourself), but, like the Seuss estate, I choose not to distribute them myself.

Is that really the end of freedom in America?

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

01/03/21 Are Superheroes Racist?

I presented in the TEDx Rutgers conference last Saturday. The talks were prerecorded and the Q&As live. Below is the draft of my talk — which, I discovered the first time I recorded it, is way over the 16-minute limit. I hope to have a link to the actual talk soon.

America loves to put heroes on pedestals. And sometimes those pedestals get knocked down. During this Black Lives Matter moment of U.S. history, we’ve seen many former heroes reevaluated and their statues removed. A statue of Stonewall Jackson stood two miles from my house in Lexington, Virginia. It was removed in December, a little over a century after it was erected.

I’m going to look at different kind of hero, one of our country’s most beloved hero types, the superhero, and when I’m done, you will have to decide for yourself whether the superhero stays on its pedestal or if it comes down too.

But let me say: I’m not an evil man who hates superheroes and wants to ruin your childhood. I’m also not a rabid liberal professor knocking over statues because that’s what we do. I grew up on superheroes. I had a learning disability and read almost nothing but Marvel comics for years: Spiderman, Avengers, X-Men.

I still have boxes of comics in my attic, and I tried to get my son to read every one of them. My daughter fell for Superman and Batman and used to have tea parties with the action figures she asked Santa for Christmas. Superheroes were my children’s childhood. I passed that love onto them.

When I started teaching college, a group of honors students were looking for a professor to teach a seminar on superheroes. My wife—she was my department chair at the time—pointed them my way. I said yes. Obviously. What could be more fun than designing a class on superheroes?

I started researching the history of the character type, filling in missing gaps, learning the cultural contexts, the politics of the periods. This led to articles, which led to books. I’m working on my fifth right now. I am a superhero scholar and a comics theorist. My kids think that’s hilarious—but in a good way.

Not everyone does. When Stan Lee died a couple years ago, Bill Maher mocked people like me. He said:

“twenty years or so ago, something happened – adults … pretended comic books were actually sophisticated literature. And … some dumb people got to be professors by writing [about them]”

And worse, Maher added:

“I don’t think it’s a huge stretch to suggest that Donald Trump could only get elected in a country that thinks comic books are important.”

I disagree. But not for the reasons Maher might think. Donald Trump got elected because we don’t think comic books are important. Macho men in tights are very very silly-looking, but they provide a window into our history that reveals who we once were as a nation and what we must do now to become a better one.

So. Let’s look at the pedestal we put superheroes on. The hero type peaked during World War II, when the U.S. was its most politically unified. The superhero embodied the fight for democracy against fascism. Captain America’s and Wonder Woman’s costume are literally the American flag. And those ideals continued into the Cold War, and beyond it, keeping superheroes linked to our greatest national values. They are our champions of good.

And that, oddly, is the problem. Because what “we” as a nation consider “good” changes, and superheroes have changed with it.

Superman premieres in comics in 1938, but the history doesn’t start there. Go back a decade and you have The Shadow on the radio. Go back another decade and you have Zorro in silent movies. Two more decades and the Scarlet Pimpernel is a hit play and best-selling novel. Those names have faded, but if you think of research as archeology, they’re just under the top layer.

It’s the next layer that disturbed me.

A standard superhero has a costume, with a mask, gloves, a cape, and an identifying emblem on the chest. That’s Batman. Lose the cape, and it’s Spider-Man and Captain America and Green Lantern and Black Panther and on and on.

Now look at the Ku Klux Klan.

There’s the costume, usually with a cape and chest emblem, and always a mask to hide a secret identity. That’s so they can conduct their self-defined heroic mission, working outside the law

because they believe law enforcement is either corrupt or inadequate. That’s vigilantism.

That’s what superheroes romanticize.

When I saw the connections, my first reaction was excitement, like “Holy shit! Nobody knows this!” And then came, “Holy shit, this is awful. I just ruined my childhood.” Unless it was just a coincidence. Giraffes and sauropods both have long necks. Triceratops and rhinos both have horns. But there’s no direct connection. Rhinos and giraffes didn’t evolve from dinosaurs.

Superheroes didn’t evolve from the KKK.

Unless they did.

I teach at Washington and Lee University—which is at this moment deciding whether to remove Confederate General Robert E. Lee from its name. I live an hour from Charlottesville, where neo-Nazis waved Confederate flags to protest the removal of a Lee statue. Drive another hour and you’re in Richmond, former capital of the Confederacy, where statues have been removed one after the other all year.

The majority were erected during the Klan’s most popular period. That wasn’t after the Civil War. The Klan disbanded when Union troops withdrew from the South. The KKK reformed in 1915, around when that Jackson statue near my house was erected.

The Civil War had been over for half a century. So why a new interest in the KKK?

Because the film The Birth of a Nation was premiering. It was an adaption of the pseudo-historical novel The Clansman, It describes how the heroic KKK formed to save the South from the despotic Republican party and the oppression of Negro rule. It is a vile novel. It was also a best-seller, not just in the south but nationally. The film was even bigger. Its racist retelling of American history was not a fringe viewpoint. It was standard belief. After its screening in the White House, Woodrow Wilson said: “My only regret is that it is all so terribly true.”

They arrived at theaters dressed in Klan robes. They were what we now call cosplayers. The same month the same cosplayers met on top the Stone Mountain Confederate monument outside Atlanta, lit a cross on fire, and declared the KKK reformed.

Five years later their membership reached 5 million, including 300 delegates at the Democratic convention. More than 50,000 marched in DC the following summer. The Klan was praised in newspaper op-eds and Sunday sermons as a force for good, especially for combatting criminal immigrants.

This is the political context of the 1920 film The Mark of Zorro. It’s one of the most successful films of the silent era. Like a Klansman, Zorro wears a mask and a cape, has an identifying symbol—his signature Z—and he keeps his real identify a secret, pretending to be a Clark Kent coward when not in costume, then dressing up to bring criminals to justice as a vigilante.

You can’t call that coincidence. Brontosaurus and rhinos, triceratops and giraffes are separated by millions of years. The Klan and Zorro reached the heights of their popularity at the same moment. That’s pop culture reflecting current events.

And Zorro was surrounded by dozens of other masked dual-identity vigilante heroes. They filled the weekly pulp magazines, comic books’ precursors, published by the same presses, including the later renamed DC and Marvel. When Bill Finger invented Batman, he based him on the pulp magazine hero The Bat by Johnston McCulley, the same pulp author who created Zorro.

Bruce Wayne has his moment of inspiration when a bat happens to fly in front of him and he decides to dress up like a giant bat to terrorize superstitious criminals, that origin scene follows the same progression as Birth of a Nation. The future creator of the Klan sits contemplating what to do, when a white child puts on a white sheet and frightens a group of Black children. The next shot the hero appears in full Klan custom—same as Bruce in his Batman costume.

And it’s not just Batman. He’s just one of hundreds of superheroes that appear in early comic books. And the Klan wasn’t a lone aberration either. They didn’t cause the problem. They reflected a national attitude. Look at Superman again. His name encodes the larger cultural history that prompted the Klan to reform.

When I started researching for that honors seminar, I typed his name into a New York Times search engine with a date range ending the month he premiered. I expected zero hits. I got 2,158. I was confused. Then I realized the play Man and Superman premiered in 1903. “Superman” was the playwright’s translation of Friedrich Nietzsche’s term “ubermensch.” Problem solved.

Except. Why are so many of the articles from the teens and twenties and thirties? And why were they not all in the theater section? In Arts & Entertainment. A ballet dancer is called a “Superman of the toe,” a singer has the “lungs of a superman.” In Sports. Boxer Jack Dempsey is called a superman. Bath Ruth is a “baseball superman.” In book reviews. Biographers called Napoleon, Genghis Khan, Cromwell, and Ben Franklin superman. In current events. Living politicians Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, Benito Mussolini, they were all supermen.

None of those refer to the play or to Nietzsche’s ubermensch. They refer to eugenics.

It means “well born.” Sir Francis Galton coined ‘eugenics’ in the 1880s. It’s how he explained so many members of the same families going to Oxford and Cambridge. They must be genetically superior. That included himself and his cousin Charles Darwin.

Darwin had published On the Origin of Species two decades earlier. It didn’t introduce the concept of evolution so much as codify it, turning a once fringe idea into a scientific paradigm.

Humans did not evolve into the planet’s dominant species because God had willed it. It happened through a random process of natural selection. Which meant it could unhappen. Humans could be usurped by some other species or humans could devolve and descend back down the evolutionary ladder. God didn’t care.

That terrified Galton. It terrified the Victorians. Eugenics was their savior. Identify the most fit, intermarry them, and breed a superior race of superhumans. What was called the Superman.

This was science. Look at the Science section of the New York Times:

- 1924: The New Superman in the Making

- 1928: Superman Can Be Developed

- 1929: Science Pictures a Superman of Tomorrow

- 1934: ‘Superman’ Evolved by Drugs is Predicted

- 1935: Key to Super-race Found in Nutrition

The comic book Superman was Earth’s future too. In Jerry Seigel’s original script, Krypton wasn’t an alien planet. It was Earth. Superman travel here by a time machine. Superman was literally the superman that science was predicting. And science was white supremacist then, because America was white supremacist.

The main association “eugenics” today is Nazi Germany. Hitler took the idea of breeding fit, and expanded it to the prevention of the so-called unfit. He started with forced sterilizations in the early 30s and expanded to mass exterminations by the early 40s. That’s how America likes to tell the story. Except it wasn’t Hitler’s idea. It was ours.

The idea of the gas chamber came from Long Island. In 1912 an American eugenics think tank published a guide for “the Best Practical Means for Cutting Off the Defective [gene pool] in the Human Population.” Their recommendations called for immigration restrictions, racial segregation, anti-interracial marriage laws, sterilization, and “euthanasia,” specifically through gas chambers. Unlike Germany, American eugenicists wanted every town in the U.S. to have its own gas chamber for euthanizing their locally unfit.

They targeted such defective heredity traits as feeblemindedness, promiscuity, criminality, epilepsy, blindness, deafness, insanity, and poverty. And all of these traits were associated with non-anglo-saxons. Eugenics wasn’t fringe science, and it wasn’t fringe politics. It was mainstream belief.

The I.Q. test was created to identify and segregate defectives.

Planned Parenthood was created to prevent unfit breeding through birth control. Indiana passed the first sterilization law, and thirty states followed. The Supreme Court declared: “It is better for all the world, if . . . society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.”

When President Coolidge signed a bill blocking immigration, he explained: “America must be kept American. Biological laws show…that Nordics deteriorate when mixed with other races.”

When Hitler wrote Mein Kampf in 1925, he applauded the U.S., urging Germany had to catch up with our advances in Eugenics. Teddy Roosevelt praised the best-seller The Passing of the Great Race by Madison Grant. It called for the sterilization of “worthless race types.” When Hitler read the translation, he said: “This book is my Bible.”

This is the cultural and political context that produced the superhero. There is no Superman without eugenics. There is no Batman without the KKK. And none of the hundreds and eventually thousands of other superhero characters could have followed them. It makes sense that the superhero has a disturbing history because America has a disturbing history. And loving superheroes, like loving America, requires facing up to that past.

Now to be clear, the creators of Superman weren’t white supremacists. They were Jewish. The early comic book industry was predominantly Jewish, and their superhero stories were overtly anti-fascist. But they were adapting a character type that was already popular. And white supremacy is in the DNA of that character. That is a historical fact that we can repress but we cannot erase. And if we can’t face it, then we remain trapped in it.

Remember what Bill Maher said? “Trump could only get elected in a country that thinks comic books are important.” He’s wrong. Donald Trump could only have gotten elected in a country that thinks it is unimportant to examine its pedestals, including comic books. Like most Confederate statues, superheroes were constructed during an explicitly racist moment. Can they now transcend that moment? Maybe. But only if we acknowledge instead of suppress their history.

This isn’t just archeology. The past isn’t buried underground. Superheroes are thriving right now on film and TV and laptop screens.

Some of them are Muslim and lesbian and Black and other traits that eugenicists wanted to weed out. But they are still romanticized vigilantes wearing costume only one evolutionary step removed from the Klan. If we allow ourselves to keep suppressing that genetic fact, then the superhero can never evolve past it.

And maybe that’s okay? The superhero is just one very silly-looking fragment of American culture. What’s wrong with preserving a childhood fantasy? Why not indulge in a heroic image of goodness and purity? Who’s it hurting?

I think all of us. I think it trains us to keep deifying past heroes by intentionally ignoring their most disturbing flaws. But if we can face up to something as unimportant as comic books, then maybe we have a chance as a nation of facing the much deeper and much more destructive legacies of our profoundly racist past.

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized