Monthly Archives: December 2018

31/12/18 That Other Gay Dynamic Duo

Recorded well over a century before Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the anonymously authored Gilgamesh is world literature’s first epic—detailing battles with monsters, a Bible-paralleling arc and flood, and an underworld-crossing ferryman. Though many of the tropes are familiar, and The Epic of Gilgamesh is a standard on countless college syllabi, Seven Stories Press released a first-ever comics version earlier this year—an impressive accomplishment in terms of both words and pictures.

Kent Dixon originated the project with his rendition of the Babylonian text—roughly 1700 words—using the dozens of published English translations, and occasional references back to the original syllabary, to craft his own hybrid prose-verse. At times poetic in form, even with an echo of pentameter (“Abundantly the guts did spill down the mountain’s slippery slope”), his rendering also emphasizes contemporary diction, calling Enkidu a “hairball” and Gilgamesh “big and bad”—and so a good fit for his target audience of undergrads and general readers.

Kent then handed his complete text to his son, comics artist Kevin Dixon, who used it as a script, interpreting and adapting freely—but also lettering every word into the graphic novel. Most adaptations might trim as needed, and to that degree the Dixons’ comic resembles Robert Crumb’s word-for-word adaptation of the Book of Genesis. It also literally resembles it, since Crumb is one of Kevin Dixon’s many artistic influences. The style is aggressively cartoonish—down to characters’ foreheads spraying drops of plewds when anxious and bursts of emanata when literally glowing with triumph. Crumb is most present in Dixon’s masterfully detailed cross-hatching, and though some of his figures are roughly reminiscent of Crumb too, their anatomy is closer to Matt Groening’s The Simpsons.

It’s tempting to read Gilgamesh and his sidekick Enkidu as world literature’s first superheroes—a dynamic duo of demi-gods who possess a litany of superpowered traits: chest as broad as an ox’s, speed of a shooting star, an itch for performing extraordinary deeds, even prayers to the god of justice. But the epic’s opening supervillain is Gilgamesh himself: a power-mad king literally raping his people. Enkidu may be closer to a superhero since he’s created in answer to the people’s prayers for a savior. But despite his good intentions, Enkidu is no match and soon is submitting to Gilgamesh too.

But maybe that was the gods’ secret plan, since Gilgamesh stops abusing his kingdom and instead teams-up with his near-equal for death-defying adventures. For no reason but want of glory, they head off to battle the monstrous Hambaba and return with his head and forest of cedar trees.

Even here, Hambaba—despite Kevin Dixon’s abundantly monstrous depictions—seems almost like a victim, a guardian of a beautiful natural landscape plundered by invaders. At least when the goddess Ishtar, furious after Gilgamesh rejects her sexual advances, releases the Bull of Heaven onto the kingdom, the heroes’ violence is protective and so actually heroic.

Still, after Enkidu’s death, Gilgamesh is sincerely heart-broken, but his attempt to reach the underworld isn’t about releasing or even visiting Enkidu’s soul. It’s about securing immortality for himself. And while that mission is unheroically self-serving, it also ends in failure—a paradoxical victory for the forces of good, since Gilgamesh, though now permanently depressed, also seems to have finally accepted his role as a just and noble king.

Kent Dixon credits his son for adding “fun and insights” to his text. That entails a wide range of very specific choices made panel by panel. Kevin Dixon sometimes defaults to what pioneering comics scholar Scott McCloud terms a “duo-specific” relationship between words and pictures. For example under the caption “Your statue, he will set at the left of his throne: all the princes of the world will kiss your graven feet,” Dixon renders exactly that, creating necessary details to visualize the words’ meaning, but to a redundant effect. When the text states that Urshanabi ran “striking his head with his fist,” Dixon adds a talk bubble “Nooooo!!” but the image otherwise repeats the caption.

His art is more engaging when it instead interprets the accompanying language. When the “revels ran late into the night,” Dixon draws Gilgamesh with a pot on his head and Enkidu passed-out and dreaming of urinating—images that fit the otherwise generic “revels” by expanding them with greater visual specificity.

Some interpretations even playfully contradict what’s presumably the text’s intended meanings. When a god warns that “You will have the legions of the dusty dead sitting down to dinner with the living,” Dixon draws a zombie attack, even adding his own talk bubble content: “No! Grandma, don’t! Aughh!”

More fun still, Dixon regularly adds visual content to expand Enkidu’s character. When “Before the alter of Shamash they laid the offering, placing the heart on top,” Dixon’s Enkidu explains “Yum!” And when “they went down to the Euphrates; they washed their hands,” Enkidu dives in head first.

Sometimes the art contradicts too—though not to any clearly communicated effect. When “back through the town they road, knee to knee and thigh to thigh, hand held high in hand,” Dixon’s heroes’ knees and thighs are not touching. It’s perhaps not surprising that this father-and-son partnership does not emphasize the homoerotic elements of world literature’s first seemingly gay couple.

The language remains extremely suggestive, with Gilgamesh dreaming that “I felt love” for a shooting star and then “was embracing it as one would a wife!” His goddess mother explains the he will receive her “blessing as if it were a bride—a bride indeed I see, a companion for my son” who he will love “as never have you loved before.” Kevin Dixon, however, avoids any homoerotic elements in his art. Even though Enkidu should be naked during his opening sequence, Dixon draws him in a loin cloth.

Though his father describes the epic as containing “adult content,” Kevin draws only one, unerect penis, and though the goddess Ishtar invites a gardener “to touch here my slit, cleft like your dates of the willowy palm,” he angles her inside a wagon to avoid drawing her vagina. And even though Enkidu and the holy harlot Shambat “coupled for a week,” most of the details are obscured by an action cloud more typically used for cartoon fight scenes.

But Dixon may be at his comics best when working with very few or no words at all. Though the epic is often heavy with language, and his captions and talk bubbles crammed with text, the adaptation also includes a nearly wordless eight-page sequence when Gilgamesh travels to a gate to the underworld guarded by scorpion men—images I assumed Dixon invented freely until I read their description in the text. Dixon extends the underworld river crossing similarly though more briefly, but most of his visual expansions fall in more obvious moments: Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s fight scene, and Gilgamesh’s fight with two lions.

Dixon scolds himself in his introduction for drawing the middle of the epic first, resulting in slight changes in Gilgamesh’s rendering as he fine-tuned the character. But far more jarring, he also alters his layout style, drawing the middle section with fewer panels and much larger lettering in contrast to the opening chapters. I also wish he had selected some style variation, either in panel content or panel framing, to indicate imagined and dreamed images, something the epic includes in abundance. Kevin Dixon even adds a chapter-long dream sequence to the end with his own interpretation of an often-deleted section believed to have been added after the original composition.

These challenges aside, the Dixons’ adaptation has earned its rightful place on college syllabi, replacing its dozens of text-only predecessors, none of which offer the range of playfully inventive visual effects only possible in the comics form.

[A version of this post and my other recent comics reviews appear in the comics section of PopMatters.]

Tags: Kent H. Dixon, Kevin H. Dixon

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

24/12/18 Tillie Walden in the new Shenandoah

One of my personal highlights of 2018 was becoming comics editor of Shenandoah under the new and amazing editor-in-chief Beth Staples. That means I get to contact new and amazing artists and ask them to appear in the journal. Tillie Walden was the first.

Tillie was on campus last spring visiting my and Leigh Ann Beavers’ comics class. After giving a lecture and running an exercise or two, she sat with our students, working on her own comics pages–including ones I now recognize from her just-released graphic novel On a Sunbeam (an early Christmas present to myself). Meanwhile, projected pages from her sketchbooks were on rotation in the gallery down the hall. Those were the ones I asked about. Clover Archer, who among many others things runs the gallery, curated Tillie’s exhibition, which is why I suggested she write an intro for her in Shenandoah. It’s below. And those amazing pages from her sketchbooks are rigth here.

A New Valence by Clover Archer

I won’t draw in a sketchbook for maybe six months, but then feel the wave coming over me again and I’ll spend a few weeks reacquainting myself with the process. And I try and always make something that I would be comfortable sharing.

—Tillie Walden

As a space for experimenting with compositions, elucidating new thoughts, and working through elements of a project outside of the physical studio space, the sketchbook can be a useful tool in support of an artist’s creative practice. Traditionally, sketchbooks have been private affairs granting artists the freedom of an inner dialogue with their own imagination. In this sense, sketchbooks were not considered finished artworks but, rather, the reification of the process leading to the artworks, a kind of mind-mapping, and thus not intended for public gaze. Like a personal diary, then, the exploratory pages of a sketchbook offer a similar promise of revelatory insight into the otherwise-secret realms of the creator’s mind. In the contemporary art world, as the context for consuming artworks has expanded beyond the physical gallery space to include digital platforms, the creative process has become more transparent. New media and technological advancements have coincided with the postmodern turn away from privileging the creator as the authority who determines when a work of art is finished. Accordingly, as the process of creation has become more visible, the artist sketchbook has gained new valence as a contender for critical attention in its own right.

Though twenty-two-year-old graphic novelist and comics artist Tillie Walden came of age after these developments had been absorbed into our cultural ethos, the young artist maintains a practice that moves back and forth along a continuum between traditional and contemporary creative practices. She publishes some of her work online, making it widely available free of charge, and has also published four books available only in print. Often, she will mix hand-drawn and digitally created elements in a single work. As Walden explains in an interview with Multiversity Comics, her catholic approach is pragmatic: “I mainly work traditionally because I like papers and pens and computers are stupid…In a perfect world, I would do everything traditionally, but I do not have time. When I am old and rich I will never touch a computer again.”

This fluid approach translates to Walden’s sketchbooks, which reflect her distinct style but differ in many ways from her published work. The compositions in Walden’s graphic novels and comics, both in individual panels and on the pages as a whole, are orderly and balanced. Her use of color is minimal, often relying on one or two tones that wash around a consistent black line used to define the subject matter. This formal restraint is a departure from the drawings in her sketchbooks, which tend to be colorful, dream-like spaces with densely packed, meandering lines. Many sketches appear to be unplanned doodles with objects and figures melting into one another, never crystalizing into a single moment or realistic environment. In these spontaneous drawings, it feels like Walden is working through her thoughts in the moment, departing from the economy of line and color found in her graphic novels and comics. The confident drawing style we see in her published work is present but expressed with a psychedelic exuberance, rather than restraint. In many sketches, it feels like Walden is allowing herself some well-deserved freedom.

Unlike other artists’ sketchbooks, Walden’s pages feel resolved, exhibiting little indication of erasure, errors, or failed experimentations. The fluid, stream-of-conscious line and dense patterning can absorb “mistakes,” turning the line into something else as it moves across the page. Instances of speculative mark-making or unfinished compositions do occur occasionally, but they become less revelatory of Walden’s process as they don’t seem to reflect the artist’s prevailing creative consciousness. Rather, the overall absence of hesitancy evidences Walden’s ability as a draftsperson and assuredness as an artist.

It is no surprise to learn that Walden is acutely aware of her viewer, even when her drawings are not intended for inclusion in a narrative publication for which she is known. Indeed, Walden has shared pages from her sketchbooks on Twitter and her website, and selected drawings can be purchased online as prints. This blurring of the line between public and private is entirely in keeping with themes in Walden’s work, emotional storytelling that draws on her own life experience with the direct honesty of a visual diarist. Yet, like her relationship to traditional and contemporary modes of mark-making, Walden’s relationship to the vulnerability of self-exposure is not straightforward. “I have a professional self, you know,” she said in a recent interview with Forbes, “a version of myself that I’m willing to share and speak on. But outside of that, I need some privacy. Memoir tears down barriers and walls in your world, which is a positive and a negative. And I’m still in the process of understanding that.”

How does a latent idea in an artist’s mind evolve into something that has the power to astonish, devastate, and delight? Even if we pull back the curtain on the creative process, there is no formula to explain the potency of art—every artist follows a unique trajectory to the realization of their work. These pages from Walden’s sketchbook may be another version of her public self rather than a lifting of any barriers to her privacy. But though she maintains these boundaries, Walden expands our appreciation of her published work by offering a glimpse of the breadth and scope of her artistic dexterity. Rather than an intimate translation of an artist’s imagination, it is this added dimension of understanding that compels us to explore the pages of Tillie Walden’s sketchbooks.

[And seriously, if you read all that and still haven’t looked at the images, you gotta go look at them right here. Here’s one of my many favorites:

Tags: Clover Archer, Tillie Walden

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

17/12/18 Secret Superhero Syllabus

Like any syllabus, the syllabus for my first-year writing seminar “Superheroes” is incomplete. It includes only what I could fit into one short, writing-focused semester. It also includes only material that I know. I know a lot about the superhero genre, so that’s a pretty good start, but it’s only a start. My students have a wide range of interests and expertise too. Their job was to combine their personal knowledge with the research know-how they learned this semester and expand our syllabus into areas of scholarly and popular writing I would never discover without them. Here’s a sample of what they unmasked:

Eric Dyer:

Abad-Santos, Alex. “Marvel’s comic book superheroes were always political. Black Panther embraces that.” Vox, 22 Feb. 2018, www.vox.com/2018/2/22/17028862/black-panther-movie-political.

In his article “Marvel’s comic book superheroes were always political. Black Panther embraces that”, Alex Abad-Santos claims Black Panther to be the most political movie Marvel has created. African-Americans seem to be particularly underrepresented in the film industry and are rarely seen as leads. In a growing political climate, it was essential for Marvel to display cultural diversity. In his article, Abad-Santos argues that it is important for the reader or viewer to see themselves in the story. Especially as an adolescent, it is meaningful for individuals to see an actor or actress of which they can relate, and African-Americans can find familiarity in Black Panther. Abad-Santos observes that the message in Black Panther is not hard to find. Additionally, Abad-Santos argues that Black Panther reflects the harsh realities of many African Americans. Furthermore, Abad-Santos notes that the superhero, Black Panther, seems to represent African culture in a positive way and sheds light on misconceptions about Africa. Black Panther had a tremendous impact across the United States as it celebrates culture and diversity. However, the film also pays attention to the more brutal and unforgiving side of black history. Abad-Santos comments on the aspects of slavery and colonization presented in the movie and how these two events contribute to the persisting inequality between races. Abad-Santos points out that some Americans automatically assume everywhere in Africa is suffering from poverty. In one scene in Black Panther, a news anchor refers to Wakanda as a Third World country. It seems like the media always portrays Africa as a country plagued with famine, AIDS, and other various negative associations. However, the nation of Wakanda is extremely prosperous and has an abundance of natural resources. Abad-Santos describes our world as one that cannot “fathom an African superpower”. This shows that most of the world lives in ignorance. Abad-Santos argues that superheroes are presented as “sociopolitical fairy tales”. Essentially, superheroes tackle internal and external affairs in the United States. He provides evidence such as Captain America punching Hitler in the face and Spider Man fighting the war on drugs in the 1970s. This shows that superheroes can be used as propaganda, especially for a younger audience. Abad-Santos references Jack Kirby, one of the creators of Black Panther, when Kirby states he realized he never integrated African Americans into his comics but was aware of the importance of their representation. Overall, Alex Abad-Santos explains the relevance and importance of Black Panther to the African American community.

Fenner Pollock:

De-Souza, Desalyn, and Jacqueline Radell. “Superheroes: An Opportunity for Prosocial Play.” YC Young Children, vol. 66, no. 4, 2011, pp. 26–31. JSTOR. www.jstor.org/stable/42731275

In their article “Superheroes: An Opportunity for Prosocial Play,” authors De-Souza and Radell acknowledge that many people suggest that superhero play evokes aggression in children. These people believe that superheroes’ actions imply that using violence will help one achieve his or her goals. De-Souza and Radell, however, refute this popular idea and, instead, argue that imaginative and pretend play instills valuable lessons into kids. They identity emotion as being the agency for growth in children in that a child must learn to regulate his or her own feelings. Teachers and parents help to develop these initial emotions. The authors, writing in 2011, claim that television and technology might take away some of children’s creativity, and instead they argue for children to use their imaginations to create superheroes and hero scenarios. The article shifts to a personal experience told by Jacqueline Radell, who serves as a preschool teacher. She was influenced to implement superhero play in her classroom by a seminar in New York that discussed the relationship between superheroes and child’s play. After returning to her classroom, she decided to experiment with the activity. She was hesitant at first to introduce superhero play in her classroom with the popular belief of aggression and fighting in mind. Since it was late in the school year, however, her students had already developed strong relationships with one another and had “self-regulation” (Radell 27). As highlighted previously, she advocated for creativity and allowed the young students to come up with their own original ideas of what a superhero is and does (a much less scholarly and elementary version of Coogan’s What is a Superhero in a sense). The results were tremendously positive. Each child blurted out ideas that consisted of “save people,” “fight fires”, or “wear capes”. Radell reports that the class discussion focused on three important, positive traits that superheroes possess: kindness, care, and help (Radell 27). Radell discusses how her students wanted to create their own names and badges, therefore emphasizing the subject of creativity. They stayed away from stereotypes such as Batman and Superman thanks to not only the guidance of Radell, the teacher, but of the lack of technology present. Radell then introduces various props of the classroom such as glasses, pencils, fabric, etc., while advocating for the importance of non-violence. The kids had no problem sharing various props. They innovatively constructed “superhero castles” and modes of transportations such as cars, helicopters, and motorcycles made of blocks and crates in the classroom. The children acted as moral superheroes who wanted to help others, as evident from “saving” the teacher when she imitated a fall or constructing a fellow superhero’s house once the blocks tumbled. Each child inadvertently learned the importance of having different perspectives and viewpoints in situations due to the fact that they played various roles in the superhero games that they made up. Each day, the children would continue this “prosocial superhero play” (Radell 28) in a nonviolent, healthy, active, and creative classroom. Radell then discusses the lessons she learned from her own students and gives tips to teachers who also want to instill this superhero pay in their own classrooms. Radell advocates for a positive introduction of the subject while at the same time allowing the kids to have freedom and a sense of control (Radell 30). Her experiment reflects the theory presented in the introduction by De-Souza that superhero play does in fact positively affect children’s creativity and confidence.

This article was also a refreshing reminder that kids can teach adults valuable lessons, not simply the opposite. These young children in Jacqueline Radell’s classroom demonstrated the importance of creativity, collaboration, and empathy which was all realized and demonstrated through this superhero play. As a kid who grew up in the early 2000s, my twin brother and I relied on imagination to keep us busy, and more times than not we made up games that related to superheroes—just like those school children. I highly recommend reading De-Souza and Radell’s article if you are interested in studying the positive, psychological impact that superheroes play in our society, especially towards young children and adolescents.

Tyler Zidlicky:

Brantner, Cornelia, and Katharina Lobinger. “Campaign Politics: The Use of Comic Books for Strategic Political Communication.” International Journal of Communication , vol. 8, 2014, pp. 248–274.

Throughout history, political parties have often used comic books as part of their campaigns. This article talks about the use of comic books in political campaigns and analyzes the influence of the mass media of comic books on the 2010 election campaign in Vienna, Austria. In the 2010 Viennese City Council and District Council election, political parties used comic books as a strategy of political advertising to promote their principles and ideals. In context, the voting age in Austria had just been lowered from 18 to 16-years-old, and this new technique was a strategy to reach the party’s new younger audience. The comic books attacked political enemies of each party and vilified their opposition by altering their physical appearances. The humorous tone of the comics is what allowed for their great success. Readers became distracted by the entertaining plot lines and characters, and thus became more oblivious to the underlying political motivations of the comics. There has been an increased number of visuals and images being used in political campaigns. This is a result of moving towards “politainment”, which is the blending of politics and entertainment into a new type of political communication. The now prominent presence of visuals in the media has shifted the political culture “from a formerly ‘logocentric’ to a primarily ‘iconocentric’ mode of communication”, meaning the visualization of politics. Images are consumed by audiences without much thought, and many critics believe that politainment is detrimental to the political system. However, even though images are understood as too simple to accurately portray political issues, they have a mysterious way of influencing the people significantly while being harmless at the same time (Brantner). Recently, comics have emerged that focus on a direct relationship between politics and entertainment. The main protagonists are political actors, or the main plot lines revolve around political issues. In 2008, IDW Publishing came out with two comic book “biographies” about Barack Obama and John McCain called Presidential Material. Additionally, in May 2011, a comic was published about Vladimir “” fighting against zombies and terrorism that demanded for democracy. Neither of these comics were produced by the politicians themselves, but by public relations experts and artists. However, the influence that they would have on popular culture and the public still impact the ways that we understand politics.

Janie Stillwell:

May, Cindi. “The Problem with Female Superheroes.” Scientific American, 2015, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-problem-with-female superheroes/.

Cindi May comments on the idealization of Superheroes by children, and how many children consider the fantasy of one day becoming a hero themselves. She notes that there is an understandable desire to be a hero and acquire all the benefits that come with being a hero: the costume, protecting the entire world with all the credit for your actions, and the powers. She also refers to recent studies, which argue that superheroes have a negative influence amongst women. While there is diversity amongst roles that woman may play within comics, from victim to hero, the majority if not all female characters are hypersexualized. The comics focus on their “voluptuous figures” to their “sexy, revealing attire” (May). May provides examples from both Spider-man and Superman to argue that male characters tend to be depicted as independent, strong heroes whose main purpose is to protect human-kind, but also tend to always need to rescue a woman in danger. Conversely, she notes that the female character within the films are seen as weak, naïve, and unable to protect themselves, while also maintaining perfect beauty and sex appeal. These characters also tend to act as the love interest of the male hero. May notes the studies which claim that the emphasis on sex appeal amongst female characters and the repeated exposure to female characters as victims can lower women’s self-esteem and body image. However, May also comments on how the genre has transformed female characters over a period of time. She uses the X-Men franchise as an example of comics that contain empowered female heroes. Storm, Jean Gray, and Dazzler all possess unique capabilities while also having intelligence and strength. May believes that exposure to these types of female characters could potentially help increase positive body esteem amongst female viewers. However, she notes that while today’s superheroes may possess greater hero skills, they tend to be depicted unrealistically and the majority are sexualized through the emphasis placed on their breasts, curves, and unrealistic hourglass figures. Many are pictured in skin-tight costumes, which also accentuate their inherent female physical traits. May argues a parallel point to her earlier claim that stronger female characters may heighten body esteem by claiming that the sexualized depiction of females within the comics may again have negative effects on female viewers’ body image and self-objectification. She further discussed the research carried out on the topic, in which female college students were asked to watch a video montage of female victims and heroines within comics and then fill out a survey on gender role beliefs, body image, and self-objectification. The research showed that the women tended to report less egalitarian gender beliefs but did not experience drops in body esteem. However, other women who watched the X-men montage reported lower body esteem. The powerful nature of the X-men heroines caused the participants to want to emulate them. Therefore, the researchers claim that the empowerment of women may have some effect on women’s self-esteem, the sexualization of women in comics simply reinforces stereotypes.

Jens Ames:

Taylor, A. (2007). “He’s Gotta Be Strong, and He’s Gotta Be Fast, and He’s Gotta Be Larger Than Life”: Investigating the Engendered Superhero Body. Journal of Popular Culture, 40(2), 344–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5931.2007.00382.x

Aaron Taylor begins with discussing the increase in the study of how culture represents bodies. Taylor says superhero bodies have been very gendered since the start of the superhero genre. The bodies of characters are super-sexualized and exaggerate gender differences. According to Taylor, the sexuality and physical emphasis of characters caused both public outrage and censorship within the industry. However, the sexualization has continued today. Male characters have ridiculous muscles and veins. Females put themselves in sexual positions and “defy all the laws of physics” with their breasts. While superhero comics are often targeted toward adolescent male audiences, comic books attract many other people as well. The bodies of characters are often invincible and do what would be impossible in the real world. Taylor states comic books are a series of static panels, with just still pictures and dialogue to tell the story. It is up to the reader to decide how the panels connect. Because of the static natures of drawings, the bodies of characters are often contorted to encourage the reader to believe action is occurring. Panels also rarely show full body shots of characters which creates emphasis on various body parts. Because they are so rare, full body shots emphasize how body parts work together. The scarcity of full body shots allows readers to put together the body for themselves, according to their own beliefs. In a more literal sense, the feedback of readers often allows fans to have some input on how characters appear. Taylor points to the fact that most of the superhero is white, middle class, adolescent males. Because of the reader composition, it is no surprise female characters are so sexualized. Taylor blames the profitability of sexualized bodies as to why the genre has not changed. In addition, superhero stories are typically timeless, meaning the stories typically do not change much over time. While women are clearly sexualized, Taylor believes men are sexualized just as much. Taylor describes male superheroes as bodybuilders in spandex, making them nearly as objectified as women. Where the two sexes differ in their portrayal is the depiction of their sexual organs. What Taylor describes as the “superpenis” is nonexistent, but the sexual organs of women are often clear. Taylor then dives deeper into the difficulty of portraying females. Women cannot be portrayed as soft, but too much muscle and hardness make women appear too masculine. When portrayed, women are virtually always portrayed from chest up, in order to show off their breasts. Taylor then shifts to the story of Batman. Batman has no love interest which makes him desexualized. Batman also has no pupils in his eyes. Despite the fact he is totally human unlike Superman or Wonder Woman, Batman acts less human than the other two. Taylor concludes by saying superheroes act as idealized bodies for normal people. But, while normal people have to work for their body to look like a superhero’s, superheroes are blessed with their bodies from birth or accident. The super-sexualized bodies of superheroes effect readers in multiple ways.

Mya Lewis:

Baron, Lawrence. “‘X-Men’ as J Men: The Jewish Subtext of a Comic Book Movie”. Purdue University Press, 2003. Shofar, vol. 22, no. 1, 2003, pp. 44–52. JSTOR, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42944606.

In this article, Baron discusses how the film X-Men (2003) and the X-Men comics accurately portray the social struggles that many Jewish Americans undergo while trying to assimilate into American society. He argues that the accurate representation of the Jewish minority group in the movie is due to the first-hand experiences of the film’s director and the comic book’s creators, as first-generation Jewish Americans. Baron touches on the life of Kirby, the self-named illustrator of the X-Men comics, and the hardships he faced as a Jewish man in America. He also examines the life of Stan Lee, another first-generation Jewish American, and focuses on his impact in marvel publications and the X-Men Comics. Baron analyzes the social issues Magneto faced during the Holocaust and underlines how these matters shaped him into a villain in retrospect to Dr. X becoming a hero. As a child, Magneto loses his family to the cruel mistreatment of the Germans, causing him to manifest feelings of resentment towards humans and create a group of evil mutants whose goal is to “overthrow mankind” (Baron 5). Dr. X, in comparison to Magneto, creates a group of mutants whose goal is to protect mankind from the threat of Magneto’s mutants, and any other inhuman threats. Baron claims that Dr. X’s want for coexistence between mutants and the American society reflects the desire to assimilate that many first-generation Jewish Americans hold. He insists that Magneto mirrors the Jewish individuals that are bitter towards Americans for the discrimination they received, and that the Holocaust, in the X-Men universe, is a metaphor for the susceptibility of the Jewish race. Baron’s article on The Jewish Subtext of a comic book is an interesting source because it approaches the idea of minorities in comics from a unique perspective. While most people would argue that there is a scarce inclusion of minorities in comics, Baron believes that Marvel has done a satisfactory job of representing minorities in their works. His article would be useful to reference when arguing that minority characters are becoming more popular in American comics, or to counter argue that American comic writers are not doing enough to represent minorities in their media. Baron’s article is relevant because it addresses the popular theme of racial minorities and it respectfully and diligently conveys Baron’s observations. His article is scholarly with minute mistakes, peer reviewed and published in a credible academic journal, making it a great source to use in a research paper or dissertation. When using this source as evidence, it is best to paraphrase the information, considering most of Baron’s evidence is quoted from other sources.

Kathleen Wilson:

Kistler, Alan. “How the ‘Code Authority’ Kept LGBT Characters Out of Comics.” History, A&E Television Networks, 28 Apr. 2017, www.history.com/news/how-the-code-authority-kept-lgbt-characters-out-of-comics.

Alan Kistler closely examines the comic “Code Authority” with his article “How the ‘Code Authority’ Kept LGBT Characters Out of Comics.” Throughout the 1950-80s, a code existed for comic books. This code consisted of different aspects that kept LGBT characters out of comic books. This code was not regulated by the government, but publishers were encouraged to abide by it because they were more likely to be able to sell to vendors if they had the code’s stamp of approval. Both Marvel and Detective Comics basically controlled the comics industry because they were the most popular. Both companies abided by the Code Authority, and because of this, their representations of society were the stories that dominated comic books, and they neglected to represent the LBGT community. Kistler explains the waves of popularity in the comic and superhero industry, and because of the comics’ prevalence in society, these stories had the ability to influence or sometimes corrupt children. Comics generally contained more conservative values, and Kistler incorporates Dr. Frederic Wertham’s point of view on this. Dr. Wertham, in 1954, warned society that comics held inappropriate messages and that impressionable children should not read them. Kistler also acknowledges Carol Tilley’s research in 2013, where she discredits some of Dr. Wethham’s ideas, but this was long after Dr. Wertham warned all of America of the comic industry’s skewed morals. In the 1940-50s, the Comics Magazine Association of America was founded in response to Dr. Wethham’s ideas, and this association generated the Comics Code Authority. This code set a precursor for what was to come for the next 30 years in the comic industry. Regulations were placed on the representation of government, crime, drugs, and romance. Only with the context of powers or technological skills could acts of crimes be portrayed. The code also prohibited drugs and sexual relations, especially homosexual or LGBT relations. The code went under regulation in 1971, and they were revised, which allowed for Marvel and DC comics to get away with more mature subjects as long as these stories had “mature reader” warnings on them. It was not until 1989 that the Code lifted its ban on the portrayal of LGBT relations. After this, DC and Marvel revealed that some of their comic stories had homosexual intended plots. The comic and superhero industry became modernized following the change of the Code Authority, as it began to include more LBGT centered plots and characters. Since Detective Comics and other publishers republish their original comics but modernize them more, some comics have been recently altered to incorporate more progressive plots. Kistler suggests that the comic industry still has a lot of progress to make. He believes that the industry needs to continue to move forward in order to include more progressive stories as cultures continue to change. Overall, comics are reflective of the culture in which they are written and read, so including more progressive topics, especially about the power of women, would broaden the comic industry’s audience.

Gabrielle Jones:

Peters, Brian Mitchell. “Qu(e)Erying Comic Book Culture and Representations of Sexuality in Wonder Woman.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, vol. 5, no. 3, Sept. 2003, doi:https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1195.

Brian Mitchell Peters argues that queer youth have always found a home and seen themselves in comics. Queer youth can relate to the double lives led by many superheroes and have felt “a queer consciousness” within these stories. Peters focuses on Wonder Woman through this lens. Wonder Woman leads the typical superhero double life; while she fights crime as Wonder Woman, she must also assume the identity of Diana Prince, an average woman. Peters understands this “normal” identity as a closet for Wonder Woman, equivalent to the proverbial closet the vast majority of queer people start out in. Diana herself has some serious “lesbian overtones,” at least according to Peters and several contemporaries of the original Wonder Woman comics. She is originally from an island populated only by women, and frequently says “Suffering Sappho!” as an illusion to the poet Sappho of Lesbos, who is mostly known for writing enough poetry about her love of women to have the word lesbian coined for the island she lived on. This catchphrase of sorts was a deliberate choice by Wonder Woman’s creator William Moulton Marston, who according to Peters seemed to enjoy messing with people in an age where McCarthyism was going strong. Peters also states that Wonder Woman’s queerness is indicated by her powers, which are distinctly unfeminine by the very virtue of being powers in a male-dominated society, in combination with her traditionally feminine costume. By the 1990s, much of Wonder Woman’s queer coding comes from the doubles she finds in her female partners and adversaries. According to Peters, male homosexuality is also alluded to by Diana/Wonder Woman. Her alter-ego Diana Prince, Peters argues, is the camp gay equivalent to the 1990s’ Wonder Woman Artemis’s lesbian heroism. Diana’s continual makeovers and varying costumes can be seen as representing drag, as can her power and anger. Her battles with her main villains, the majority of whom being women, are also incredibly sexual according to Peters. Diana’s bracelets must be tied in order for her to lose her powers and be subdued. Peters argues that this creates an explicit theme of queer sexual domination. Diana’s battle dialogue also contains queer overtones, as in one comic Cheetah specifically alludes to kissing Diana in order to subdue her and Poison Ivy refers to her as “Wonder-Babe”, and the battles themselves resemble boxing or sparring matches, which have their own overtones of homosexuality and desire. Peters also claims that Artemis’s downfall is in her masculinity. She is too masculine, and therefore to queer, to function properly in society, and thus is killed by virtue of her masculine traits, i.e. impulsiveness.

Ethan Childress:

Nelson, Adie. “Halloween Costumes and Gender Markers.” Psychology of Women Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 2, 2000, pp. 137–144.

In her journal article “Halloween Costumes and Gender Markers”, Adie Nelson of the University of Waterloo argues that the costumes worn by young children on Halloween reinforce traditional gender roles between males and females. She argues that our modern Halloween uses costumes to categorize young men and women into roles in our society, including gendered superheroes and villains. Nelson argues that as babies, boys and girls are put in traditional baby clothes, normally frilly and ladylike garments for females and sport or superhero themed baby wear for boys. She speculates that Halloween costumes continue to reflect this gendered nature of dress later in the child’s life. To support this argument, Nelson conducted a study using 469 children costumes that were available in her local costume stores around Halloween. These costumes were analyzed based on the gender of the costume wearer on the cover of the product, which Nelson argues is a gatekeeping device for the products purchase that restricts members of the opposite sex purchasing it. The pictures for boy costumes were found to normally show a boy wearing running shoes and with a traditional boyish haircut, short on the sides and top, regardless of the nature of the costume. Girls were depicted with long hair and wearing traditionally feminine clothes like stockings and bows. Other characteristics that were used to categorize the costumes included the colors associated with the costume and the nature and theme of the costume. From these characteristics, the costumes were separated into boy and girl categories. One more group was included in the categorization, the costumes that fell neither in the feminine or masculine side, such as gender-neutral animals and inanimate objects. After the initial separation took place, the costumes were separated into hero, villain and fool categories within each of the existing 3. The hero’s subcategory consisted of those with superpowers, such as Superman and Xena the Warrior Princess, another was traditional male and females heroes such as Robin Hood and Cinderella and the final subcategory was heroes that fell along gender roles, such as Doctors and a Team USA Cheerleader. Nelson argues that these costumes are meant to show positive role models for young children, but they are extremely gendered. Villains constitute the other side of the hero in costumes, they are meant to show their evil so that they can be hated by others. Subgroups include symbolic representations of death, monsters such as werewolves and vampires, and anti-heroes such as pirates and Catwoman. The last category in the broader sections of male and female costumes are the fool costumes, typically clowns and the other “gag gift” costumes like pizza and shampoo. When all data was gathered, it was found that of the male costumes 41% were heroes 31.8% were villains and 27.2 were fools. Of the female costumes 44.6% were heroes, 18.4 percent were villains and 36.9 percent were fools. In both male and female groups, the hero category made up most of the costumes. However, Nelson found that while the male costumes frequently depicted Superheros and those with supernatural powers, girl costumes of heroes fell into the subcategory of social heroes, such as the beautiful bride and pretty waitress. Nelson speculates that the lack of female superhero costumes exists because of the lack of female representation in comic books, further stating that when females are depicted, they exist as a man’s sidekick or love interest. Furthering this argument, boy villain costumes are seen to depict boys as actual villains from comic books, pirates or scary monsters, while girl costumes played on their sexuality, seen in such costumes as a sexy sorceress or witches, devoid of the gore and fake blood found in boy villain costumes. The effect of the under representation of females in comic books is shown to have a real life effect on the gendered costumes children wear on Halloween, forcing women further into the identity of the life givers and the pretty and calm people society has come to expect them to fulfill.

George Daskalakis:

Bauer, Matthew, et al. “Positive and Negative Themes Found in Superhero Films.” Clinical Pediatrics, vol. 56, no. 14, SAGE Publications, Dec. 2017, pp. 1293–300. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0009922816682744

This journal article written by Matthew Bauer for the scholarly journal Clinical Pediatrics investigates the messages that superhero movies portray, and more specifically lessons that the younger audience is taking away from the films. Bauer analyzes 30 films ranging from family films with G and PG ratings, and blockbuster films with PG 13 ratings. Notable movies from the family films include Superman (1978), The Incredibles (2004), and Big Hero 6 (2014). More well-known movies were included in the blockbuster section, like Spiderman 2 (2005), The Dark Knight (2008), and The Avengers (2012). In these 30 films, he studied the positive message that the superhero is conveying to the audience, and the negative morals that the villain or in some instances the hero delivers. After a close synthesis of the films, Bauer came to the conclusion that the most common positive theme was “helping others and positive relationships” and the most common negative theme was “fighting/violence and the use of weapons.” Bauer then discusses the impact these morals can have on children, the primary audience for most superhero films. He argues that the positive themes like helping others allows children to foster relationships with other children and teaches them how to be a good person. He also emphasizes, however, that children are just as likely to adapt the negative themes of the films just as much as the positive ones. He argues this because in many instances the heroes resort to violence in order to achieve their goals, and reciprocate the violence of the villain they are opposed with. He concludes with a discussion on how even though the most popular theme of helping others is beneficial to children, there should be a wider variety of themes including taking responsibility for your actions and empowering female characters. I think the most important aspect of Bauer’s investigation was how even though all superhero movies promote good morals to children, they still all include violence. I find this extremely interesting because as we discussed in class, the primary audience for comic books and superhero movies is the adolescent boy. The adolescent boy tends to be very violent and can be influence to be even more violent if they see Batman beating up the Joker or Superman hurling General Zod through a skyscraper. Also, this paradox of good morals versus violence in all superhero movies is very interesting from a viewer standpoint because the viewer is never questioning the morals of the hero, even if he or she is being violent.

Brad Stephenson:

Johnson, Jeffrey. “The Countryside Triumphant: Jefferson’s Ideal of Rural Superiority in Modern Superhero Mythology.” Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 43, issue 4, Popular Culture Association, 2010, pp. 720-737. Wiley Online Library, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1540-5931.2010.00767.x

In “The Countryside Triumphant,” Jeffrey Johnson argues that Thomas Jefferson’s beliefs about rural settings being superior to urban lifestyles is seen in superhero comics, such as Batman and Superman. Jefferson believes rural citizens are superior to their urban counterparts. He claims that farmers and rural folk focus on morals while urban citizens are corrupt. Jefferson believes that the United States has a responsibility to be a rural country because it has vast amounts of land while European nations are cramped and forced to be urban societies. Johnson explains that there is a common misconception that comics applaud the urban lifestyle, but, in reality, comic books compliment the rural way of living just as Jefferson does. Cities in comics emphasize the negative factors of real-life cities, and superheroes address these issues with their heroic powers. Johnson chooses Batman and Superman as examples of comics upholding Jefferson’s beliefs because they have the longest lasting impact on American culture. Batman and Superman are some of the first modern superheroes ever created and have been consistently popular among Americans since their conception. Another reason Johnson chooses Batman and Superman is because their comics portray the feelings of Americans during the time period they were created. Batman and Superman comics can give readers a historical and cultural context of the time period when they were created because of their popularity. Because many people connected with Batman and Superman, the values of the audience during that time are seen in the dialogue and artwork. Finally, Batman and Superman are clear examples of how Jefferson’s ideals appear in comics. Johnson argues that these two comics in particular highlight the rural supremacy of morals and lifestyles Jefferson believes in. Johnson goes into detail about each superhero, including how Jefferson’s views exist in the origin stories of both Batman and Superman. Superman is born on Krypton, which is destroyed by so-called environmental factors. The planet creates highly advanced technology, which leads to its downfall. Johnson compares how the technological advancements seen on Krypton can relate to the corrupt cities that Jefferson describes. The downfall of an entire civilization and planet is due to the advancement of technology, which upholds Jefferson’s view of cities being negative to society. Superman is then placed in an evacuation pod and sent to earth. Johnson focuses specifically on the place in which he lands: rural Kansas. Johnson finds significance in where Superman lands because due to the location of the landing, a family with rural morals and lifestyles discovers and raises him. Superman decided to aid people in need because he is raised in a rural setting, which teaches him how to treat others. Batman has a contrasting origin story, but rural supremacy is still seen throughout. Batman grows up in a city, but on the outskirts where he is not corrupted by the urban setting. Bruce Wayne still interacts with the corrupt people of the city, but he does not become evil himself because of his family’s morals. While in the city, Wayne’s parents are murdered by a robber who resides in the city. Bruce discovers the corruption Jefferson describes through the murder of his parents and decides to avenge them because of the city itself. Johnson argues that Batman is a darker superhero because of his proximity to the city and the effect that the corrupt people have on his family life. Bruce Wayne creates his superhero persona in reaction to the corruption of cities, while Superman fights crime because of the positive morals that he inherits from his rural family.

Jack Rawlins:

Fitzgerald, Barry W. “Using Superheroes such as Hawkeye, Wonder Woman, and the Invisible Woman in the Physics Classroom.” Physics Education, vol. 53, no. 3, 2018. IOPscience, http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1361-6552/aab442/meta.

Barry W Fitzgerald is a research scientist at Delft University of Technology. In this paper, which appears in Physics Education, Fitzgerald takes specific examples from superhero films and comics, and applies the world of physics to them in order to discover how realistic they really are. He has written a good deal of other material relating science and physics to the world of superheroes, and his expertise shines through in this particular work.

In the introduction, Fitzgerald takes a slight spin on this topic of science and superheroes and discusses the potential for applying the popularity of superheroes and superhero films in the classroom. He argues that superheroes can help to emphasize how the laws of physics are not only applicable and important in their fictional worlds, but in our world too. In general, he makes it clear that a lot of good could come from integrating the popularity of superheroes into the curriculum of science courses.

Fitzgerald’s paper is broken up into three distinct sections, which each include an example of a physics subject from the world of superheroes. The first example is the application of linear motion to Hawkeye, which is rather fitting as the extent of his abilities relies solely on this area of physics (sorry Hawkeye). The example he uses is from The Avengers (2012), when Hawkeye fires an explosive trick arrow at Loki. Fitzgerald goes on to examine the actual physics of this (mostly CGI) scene from the film and does so with various possible values for the speed of Loki, and the distance between Loki and Hawkeye at the moment that Loki catches the arrow. For someone who isn’t enthusiastic about physics, the figure and equations given may be a touch daunting, but with a slow and careful examination of them, anyone can take something away from this example, even if it’s merely being impressed with Hawkeye’s archery skills.

The second example is of Wonder Woman and the bulletproof nature of her gauntlets and shield. Fitzgerald again examines the film adaptation, Wonder Woman (2017). The physics topic under question in this section of the paper is energy, or more specifically, the conservation of mechanical energy, as well as momentum. Fitzgerald discusses the physics of the entire process of a gun being fired, and even tackles the possible structure of her gauntlets. This section also may seem intimidating, but Fitzgerald again manages to make it easy to understand.

The third and final section delves into the physics of the Invisible Woman, and how optics could potentially lead to the creation of true invisibility cloaking technology. This is by far the most challenging example to understand, as optics on a microscopic level can be rather confusing. Nonetheless, it is still interesting to read about the physics of invisibility, and exciting to hear about the possibility of it in the future.

Fitzgerald takes his expansive knowledge on physics and his clear interest in superheroes to create a paper that is engaging and enjoyable. This paper seems to require at least a touch of interest in physics in order to read it, but even without that, the common superhero fan could surely take something interesting from Fitzgerald’s work.

Alexa Donsbach:

Fishwick, Elaine, and Heusen Mak. “Fighting Crime, Battling Injustice: The World of Real-Life Superheroes.” Crime, Media, Culture: An International Journal, vol. 11, no. 3, 2015, pp. 335-356., doi: 10.1177/1741659015596110.

This article is a scholarly source about the lives of thirteen “Real-Life” superheroes. These people from all around the world have devoted their lives to fighting crime, providing support for their communities, and battling injustice. It explores the ‘carnival of crime’ by arguing that risk, pleasure, excitement, and transgression are traits of both ‘doing good’ and ‘wrongdoing’. The interviewees are not what you would typically expect to be real life superheroes. For example, one is a former prostitute who calls herself Street Hero. She uses martial arts to protect women working on the streets since prostitutes are often times in dangerous situations. Her disguise is a black eye mask, a black busier, and black knee-high boots. Another real life superhero is a man from Brooklyn called Direction Man. He helps lost tourists and locals. His disguise is a bright orange, vest, a pair of thick black goggles, and lots of maps within his pockets. Another example is Red Justice who works as a substitute teacher from Woodside, Queens. Her disguise is red boxers over jeans, a red cape created from an old T-shirt, and a sock with eyeholes worn over her face. She encourages young people on the subway to give their seats to those who need them more. All the individuals interviewed call themselves real life superheroes, but I think this source is important and helpful to the Superhero Syllabus because it would be interesting to debate which of the individuals involved count as Real Life Superheroes. I would wonder if the class would decide to define Real Life Superheroes in a similar way they defined Superheroes in general or whether the female superheroes and the real life superheroes would have similar trends or if people felt that on the screen females were portrayed in a less appropriate way. I think that the fact that these individuals do not have extra-terrestrial traits might be something that deters people from counting them as superheroes but the fact that they dress in disguises and dedicate their lives to helping people might make others feel differently. In discussions, people can refer back to articles from other units about what defines superheroes.

Amanda Pinckney:

Mottram, James. “Where modern politics has failed, superheroes have risen.” The National, The National, 14 July 2016, http://www.thenational.ae/opinion/where-modern-politics-has-failed-superheroes-have-risen-1.167475.

“Where modern politics has failed, superheroes have risen,” written by James Mottram, presents a subjective argument concerning the political climate in superhero films and in the real world today. Mottram begins the article with the declaration of the superhero genre as one of the most widespread genres in the large-scale entertainment industry during the twenty-first century. The article centers around the claim that current superhero movies depict the convoluted political climate in modern-day America that needs to be addressed, however, these issues are not being addressed, according to Mottram. In the movies Captain America: Civil War and Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice, the heroes are controversial in some ways; they blatantly act against their government by committing crimes and engaging in civil disorder. These plot devices brought into question government’s “legitimate use of force” and the “very integrity of government institutions.” Another example of political controversy presented in Captain America: Civil War is when the Avengers engage in Nigerian affairs. Mottram reasons these matters presented could be argued over just as easily in the United Nations. He then proclaims that though all countries are responsible for discussing the issue of involvement in foreign affairs, the United States has even more of a responsibility and because our government neglects such matters, it is up to movies to bring about these political discussions. Some plot devices in Iron Man 2 challenge US policy and authority, which Mottram argues should be happening in real life too. Mottram then goes onto compare Batman: The Dark Knight Rises with the then presidential candidate, Donald Trump. For example, Trump is an outsider in terms of the political system and is seeking to bring justice to the people of his society, just like Batman. Mottram argues that most recent superhero films are directly correlated with the political climate of this time period and that superhero movies intentionally reflect the controversies in society. The absence of political dramas in Hollywood is what caused filmmakers to inject political ideas and philosophies into the superhero genre, beginning with Marvel’s Black Panther during the 1960s’ Civil Rights Movement. Though Christopher Nolan rejects the theory that he framed The Dark Knight Rises as political, Mottram believes it is obvious that the movie is politically driven; he believes that the plot mirrors the Occupy Wall Street Movement and that the movie supports a specific type of government. Mottram concludes his argument with the claim that the American government has failed us in protecting the public’s beliefs and ideals, causing the public to look to superheroes as the ones who defend our views.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

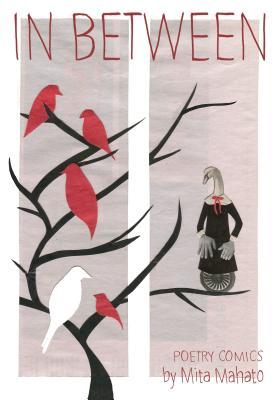

10/12/18 Meet Mita Mahato at the new Shenandoah

I first came across artist Mita Mahato through her poetry comics collection In Between published by Pleiades Press in its Visual Poetry Series. I recommend it and all of the other works available at Mahato’s website, but most of all I want to recommend her most recent comic, “Lullaby,” published this month at the new Shenandoah. A segment is featured on the cover:

Shenandoah was founded in 1950, but I’m calling the journal “new” because, after an impressive quarter century with Rod Smith at the wheel, editorship just passed to Beth Staples. Her first issue went live last Friday. Since I’m also Shenandoah‘s first comics editor, I’m feeling pretty damn good right now. In addition to an amazing range of poetry (Lesley Wheeler is the new poetry editor), translations (Seth Michelson is the new translations editor), fiction, and nonfiction, the issue includes two comics artists: Mita Mahato and Tillie Walden. I’ll say more about Walden next week, but right now I want to share our interview with Mahato.

CG: Unlike the majority of literary and artistic forms, “comics” does not have a single definition or set of requisite qualities, and so not all viewers will agree whether a given work is or is not a comic. Happily, your “Lullaby” falls into the exciting, contested, in-between area. Many of the conventions most associated with comics are absent: speech balloons, panels, gutters, even identifiably repeating characters. Shenandoah is publishing it as a comic—the first ever published by the journal—but what do you consider “Lullaby”?

MM: Working with layers of paper to construct my images means that I experiment with the comics medium in different ways than artists who work with ink. The vocabulary is similar, though. During the creative process, I’m usually thinking about panels and gutters—areas for content and areas for visual lacunae. If you look closely at “Lullaby,” you might identify images that operate as panels—like the rectangles and other shapes that represent sea and land. If we do approach these shapes as panels, then we might consider how the gutters between them function. Do they encourage readers to imagine narrative bridges, or do they suggest spatial barriers? Another way that the comics medium inspires my work is in its use of dissonant forms of signification. In most comics, that dissonance comes through the interplay of word and image. In “Lullaby,” I tried to invite it by playing with different visual signifiers—for example, the photographic hands and the more abstract, cut-paper imagery.

That is all to say that the creative process that went into “Lullaby” is indebted to the comics medium and I’d consider it a comic. Readers might think differently—and I welcome those complicating responses. I think it’s pretty wonderful that Shenandoah is providing a platform for artists and readers alike to explore the expansive possibilities of the comics medium. And I’m thrilled that “Lullaby” will be part of that conversation.

CG: Comics were traditionally drawn on paper, first in pencil, then finished in black ink, with color added during the printing process. We understand your process is very different. Can you give us a sense of how you work?

MM: My process can take a few different paths, but more often than not, I start with pencil on paper, too. Most of the visual elements you see in my work began with a sketch that served as the basis for the cut-paper images. Once I draw a “template,” I use it as a guide for cutting paper shapes that I paste together to form the final image (think of a how a sewing pattern works). Sometimes, the cutting is more instinctive than methodical—like the waves or crop rows in “Lullaby” (which were done without a template) or when I use traditional collage technique. Once a page is done, I scan it, complete any needed cleanup in Photoshop, and then print it. Because I work in layers, the scanning process retains shadow lines, which is what makes one-dimensional images appear to have texture and tooth.

CG: “Lullaby” is also a wordless comic. Some of your other works include words, either as narration or as speech in semi-traditional balloons, but in “Lullaby” you leave the non-narrative imagery to do all of the work. But there is a sequence, a kind of logical or at least intuitively evocative progression. Did you have a traditional story in mind? And however you began, why were words the wrong means to express it?

MM: I had the title in mind pretty early on and it might provide a way into answering these questions. A “lullaby,” of course, is a song that aims to put one to rest, sometimes (as in “Rock-a-bye Baby”) slipping into dirge territory and threatening ultimate rest. The images that sing the dark song of this lullaby were inspired by the plight of the southern resident killer whales, which are endemic to the Puget Sound region where I live. Human activities, especially those related to river management and chemical pollution, have brought the population of this unique culture of whales down to fewer than eighty individuals. Because the song that “Lullaby” sings is about humanity’s undeniable role in species extinction, I wanted to draw attention to collective actions over individual voices. I wanted to spoil the consumer’s daydream of quiet seasides. I wanted to expose that the lullaby we are singing to these whales is a deadly hum made up of pleasures and habits that have become so everyday to us that we don’t register their impact outside of our own, bored gratification. The absence of words gave me space to orchestrate a visual clatter; I wanted the pages to be loud with the invention, industry, and perspective of free enterprise. Even when we aren’t speaking, our presence is constant, crass, deafening.

BS: “Lullaby” is both intensely sad but also incredibly beautiful. How do you see those two emotions—delight and sadness—working together in your work?

MM: I think that any emotion that my art elicits is probably shaped by the very strong feelings that I have about the fundamental and insistent relationship between form and content. Because I gravitate toward themes of loss, I tend to use old, discarded newspaper, magazines, packing tissue, maps, etc. to create the images in my work. Commingling with this generally mournful content, however, is the exuberance I feel in the process. There is something so joyful about taking old paper that is bound for the recycling bin, or paper that is designed for a purpose that is no longer in play, and transforming it for new use. What you may be seeing in “Lullaby” is this dual action that I bring to my work—to grieve and to create. In “Lullaby,” all the cut-paper elements (the sea panels, the whales, the boats, the hands, etc.) are made from the color patches in newsprint advertisements or the grayscale images of photojournalism. I like that the resulting images materialize both bereavement and jubilation in their exhibition of new imagery born out of cut and pasted remains. Loss does not always entail transformation, but art made in response to it might at least encourage some pause and some reflection.

[And if you haven’t yet, now you really have to check out Mahato’s “Lullaby” here.]

Tags: Beth Staples, Mita Mahato, Shenandoah

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized