Monthly Archives: May 2017

29/05/17 Rereading The Fantastic Four #1-9 (1961)

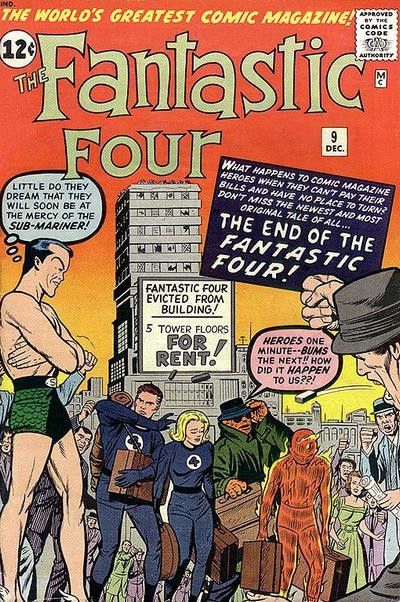

Stan Lee suggested a central “gimmick” in his original 1961 synopsis for the Fantastic Four:

“let’s make The Thing the heavy—in other words, he’s not really a good guy … Let’s treat him so the reader is always afraid he will sabotage the Fantastic Four’s efforts at whatever they are doing—he isn’t interested in helping mankind the way the other three are … the other three are always afraid of The Thing getting out of their control some day and harming mankind with his amazing strength … The Thing doesn’t have the ethics that the other three have, and consequently he will probably be the most interesting one to the reader, because he’ll always be unpredictable.”

Although Ben Grimm is an “ex-war hero,” Lee describes him as “surly,” “unpleasant,” and “brutish,” even before radiation transforms him “in the most grotesque way of all,” making him “more fantastically powerful than any other living thing.” Early issues emphasize the same qualities. While Kirby and other artists had previously drawn superheroes as uniformly handsome, the Thing is “a walking nightmare” with a misshapen body and a face as unattractive as Moleman’s. In the second issue, Sue whispers to Reed: “Sooner or later the Thing will run amok and none of us will be able to stop him!” and Ben, “a juggernaut of destruction,” confesses: “sometimes I think I’d be better off—the world would be better off—if I were destroyed!” Many readers felt the same about nuclear weapons.

Even aside from the Thing, Kirby and Lee portrayed the Fantastic Four as superheroes who produce rather than assuage anxiety. Kirby opens the first issue with an image of frightened pedestrians pointing at the flare Reed has fired to gather the team; police officers remark that “the crowds are getting’ panicky!” and that “[r]umors are flyin’ about an alien invasion!” During their origin sequence, Johnny calls both Ben and Reed “monsters,” before uncontrollably transforming into a Cold War version of the pre-Code Human Torch and accidentally starting a forest fire. “Together,” declares Reed, “we have more power than any humans have ever possessed,” a familiar superhero refrain now given new nuclear-era meaning.

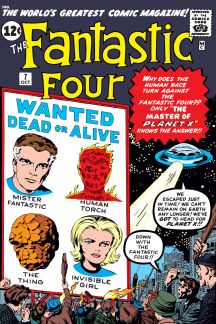

The second issue opens with a three-page sequence of the Fantastic Four committing acts of sabotage, causing news agencies to declare them “public enemies” and “the most dangerous menace we have ever faced!”—an opinion repeated in #7 when a “hostility ray” turns the world against them as “four monsters,” “the worst menaces ever to threaten this land!” The acts of sabotage were actually performed by shape-shifting Skrulls, and though the Fantastic Four are not powerful enough to defeat “the mighty invasion fleet menacing Earth,” they end the “stalemate” by showing the Skrulls other Jack Kirby drawings from Strange Tales and Journey into Mystery and so convincing them that humans have armies of “monstrous” warriors ready to protect them. The first cover features one such monster, only now the Fantastic Four serve as monster-fighting monsters trying to protect the city from it—a defining introduction for the MAD-era superhero type.

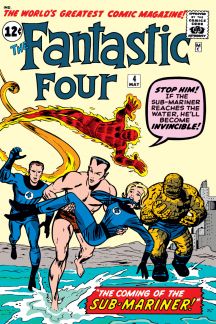

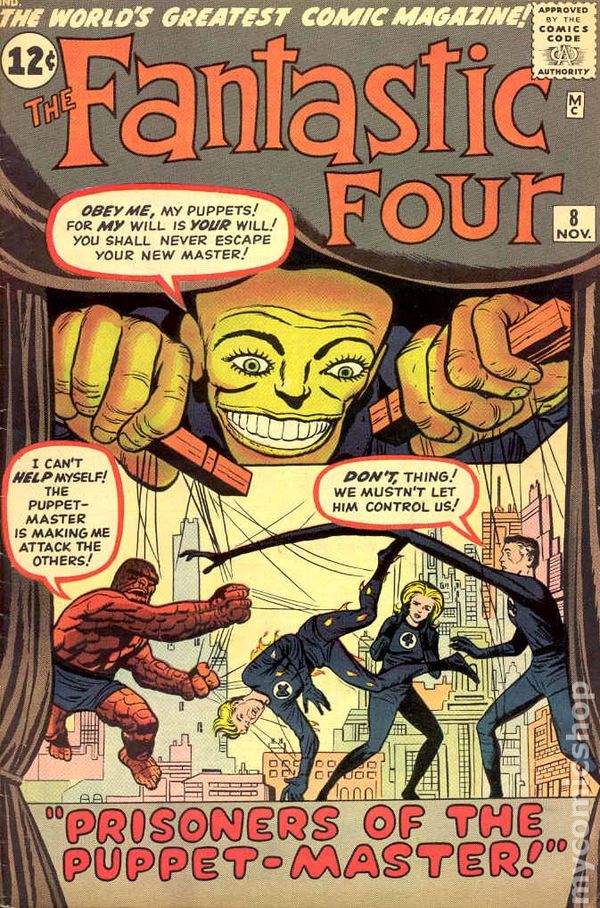

The Fantastic Four’s early antagonists evoked similar atomic fears with striking repetition. Moleman targets “every atomic plant” (#1), the Skrulls attack a “new rocket” test site (#2), Miracle Man steals an “atomic tank” (#3), and the 1940s Sub-Mariner vows revenge on the human race when he finds his underwater city destroyed: “The humans did it, unthinkingly, with their accursed atomic tests!” (#4). Dr. Doom, after bringing “forth powers he could not control” (#5), stokes the Sub-Mariner’s hatred, describing “that monster of a bomb” that destroyed his civilization (#6). The Thing mistakes an alien spaceship for “a new missile test,” while on Planet X, “Driven by fear and panic, our people are turning against each other! Soon nothing will be able to stop the riots … nothing except the doom which is hurtling toward us!” (#7). Finally, the Puppet Masters controls his victims by carving their likenesses in “radioactive clay” (#8).

Lee’s “gimmick” to include a bad guy within a team of good guys altered the standard superhero plot structure by splitting the heroes’ focus between fighting external threats and containing an internal one. Alan Moore, reading The Fantastic Four #3 as a child, had “the impression that [the Thing] was on the verge of turning into a full-fledged supervillain,” not “the cuddly, likeable ‘Orange Teddy-bear’ of later years. Stan Lee recalls writing the character in a 1981 interview:

“I tried to have Ben talk like a real tough, surly, angry guy, but yet the reader had to know he had a heart of gold underneath … People always like characters who seem very powerful yet, you know they are very gentle underneath and you know they would help you if you needed it.”

Lee’s recollection is of the later characterization, not the Thing of 1961, whose surliness was not a disguise. When Ben says to Sue in the first issue, “Now let’s go find that skinny, loud-mouthed boy-friend of yours!”, Lee scripts her response at face value: “Oh, Ben—if only you could stop hating Reed.” According to Lee’s original synopsis, Ben “has a crush on Susan,” “is jealous of Mr. Fantastic and dislikes Human Torch because Torch always sides with Fantastic,” and “is interested in winning Susan away from Mr. Fantastic.”

Despite Lee’ stated intention, his and Kirby’s rendering and readers’ perceptions of Ben grew more sympathetic. Ben complains to Reed: “At least you’re human! But how would you like to be me?” and Sue herself is sympathetic: “Thing, I understand how bitter you are—and I know you have every right to be bitter!!” When Ben returns to human form for a few moments after passing through the radiation belt again, Torch consoles him too: “She’s right, pal! That was just a start!” In #3, despite renewed fighting with Torch, Ben intervenes to save Reed’s life: “Reed can’t dodge those dum-dums forever, I gotta do something!!”

By #6, Kirby and Lee are no longer portraying overt conflict between the characters, and with #8—coincidentally on sale during the Cuban missile crisis—Ben’s “crush” ends and his character is redefined by the introduction of an alternate love interest. The Puppet Master’s blind step-daughter, Alicia, disguises herself as Sue, fooling all of Sue’s male teammates. Though Ben suffers another temporary transformation to human form, Alicia’s love is permanently transforming: “This man—his face feels strong and powerful! And yet, I can sense a gentleness to him—there is something tragic—something sensitive!” The Thing transfers his affection to Alicia, who reciprocates and humanizes his previously inhuman character: “the clinker is—she likes me better as the Thing!” In the following issue, Alicia calls Ben “my white knight! You are good, and kind, and you will never desert your friends when they need you most!”, prompting Ben to hug his teammates: “us white knights don’t desert their companions in arms! I’m with ya, gang!”

Marvel began with a Cold War plot gimmick that resulted in unplanned character complexity and then ad hoc revision, producing the unified family-like Fantastic Four that would define the series and a new superhero character type that would define the Marvel universe.

Tags: 1961, Cold War, Jack Kirby, MAD, Stan Lee, The fantastic four

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

22/05/17 How Violent Are Superheroes?

When I ask my students to describe superheroes, they typically call out adjectives like “strong” and “handsome” and “moral.” I usually have the chalkboard covered before someone get around to “violent.” But violence is arguably the most defining quality of the genre.

Beginning with Detective Comics #33 and continuing with Batman #1, DC regularized Batman episode lengths to a Golden Age norm of twelve to thirteen pages. Of those first seven episodes, combat occurs on an average of seven pages—or roughly half of each episode. Beginning with Amazing Spider-Man #3, Marvel regularized Spider-Man’s episodes to a 1960s norm of an issue-length twenty-one or twenty-two pages. Averaging issues #3-9, combat occurs on eleven pages—or again roughly half of each episode.

If superhero comics draw from ancient myth, they are not mini-odysseys but mini-Trojan wars. Since 1939, Superman has waged “his never-ceasing war on injustices,” and Bruce Wayne has spent his life “warring on all criminals.” Their initial battles against a human criminal class expand to wider conflicts against fellow superhumans in which superheroes, ostensibly motivated to protect society, appear to relish combat itself. When first facing the Joker, Batman declares: “It seems I’ve at last met a foe that can give a good fight!” And Spider-Man laments two decades later: “It’s almost too easy! I’ve run out of enemies who can give me any real opposition! I’m too powerful for any foe! I almost wish for an opponent who’d give me a run for my money!” Comics often fulfill this wish by pitting superhero against superhero, a trope Alan Moore parodies in Watchmen when an interviewer asks Ozymandias about the Comedian:

NOVA: I heard that he beat you in combat, back when you were just starting out …

VEIDT: Yes, well, that was a case of mistaken identity and general misunderstanding. For some reason it happens a lot when costumed crime-fighters meet for the first time. (Laughter)

Mark Waid and Alex Ross extend the theme to its logical extremes in Kingdom Come, which is filled not with “heroes”, but rather

their children and grandchildren. […] progeny of the past, inspired by the legends of those who came before … if not the morals. They no longer fight for the right. They fight simply to fight, their only foes each other. The superhumans boast they’ve all but eliminated the super-villains of yesteryear. Small comfort. They move freely through the streets…through the world. They are challenged … but unopposed. They are, after all … our protectors.

Ross expresses the warriors’ joy of combat through the near-photorealistic grin of a downed superhuman and the maudlin tears of a human child fleeing falling rubble. The photo-like yet somehow still-bloodless renderings also reveal the core contradiction of superhero comics: the simultaneous celebration and avoidance of violence.

While superheroes may evoke ancient epic traditions, their paradoxical approach to violence may place them in a more specific sub-category, what my colleague Edward Adams terms the “liberal epic”: “a revivified heroic tradition” that glorifies “war and violence in the cause of liberty” (22). Adams identifies

two distinctive features of all liberal epics: first, an apologetic strategy for justifying this war as a worthy exception to a general rule […]; second, a concerted effort to limit or sanitize the public’s access to graphic representations of the liberating soldier-heroes’ acts of violence and domination—an effort, moreover, that has foregrounded a concern not to shock. (5)

Although too recent to be termed “universal,” the liberal epic is both multi-national and centuries-long, beginning with the French archbishop Fénelon’s Homer-inspired yet war-critical The Adventures of Telemachus in 1699 and Alexander Pope’s 1715 The Iliad of Homer. Where Homer presents combat in graphic and arguably glorifying detail, Adams argues that Pope’s “concision in translating Homer’s violence,” “his implicit omission of the nonpoetic material reality of Homer’s battle scenes,” and his preference for “more distanced and generalizing heroic couplets” and “poetic verbal analogy” “betrays his fundamental objection to epic” (75).

The superhero genre shares both the objection to and the extended focus on violence. Where liberal epic employs poetic diction to obscure its subject matter, comics achieve similar effects through visual devices. To stop a “blood thirsty aviator” in Action Comics #2, Superman leaps in front of a plane; Shuster draws the plane plummeting out of the frame, but instead of its impact and the death of the pilot, the next panel features another character who “witnessed the crash.” Batman kills his first adversary on the third page of his first adventure, sending a “burly criminal flying” from the roof a two-story house. Bob Kane does not draw the presumably fatal impact but does include the criminal’s barely discernible body on the sidewalk two panels later.

Though most superhero violence is non-lethal, even the broken noses and bloodied lips that would result from real-world punches often go undepicted. The 1966 Batman TV series parodied the comic book norm of sanitized violence by replacing live-action punches with cut-away shots of drawn sound effects such as “POW!!” and “BOFF!!” The stylization literally blocks its own content. Despite the TV parody, superheroes comics maintained the approach. In Green Lantern Co-Staring Green Arrow #77, Neal Adams draws soldiers charging across a mine field and then in the next panel entirely obscures their bodies with a bloodless “BLAM” below the caption, “Some die immediately.” For Wolverine #4, Frank Miller depicts the death of a Japanese crime lord through framing and closure effects. In the penultimate panel of the combat sequence, Wolverine’s claws are sheathed and his fist hovers in front of the warrior’s face; the final panel frames Wolverine’s face, partially cropped arm, and the letters “SNIKT,” the signature sound effect of his extending claws. Miller does not draw the claws piercing the enemy’s head.

Like the liberal epics of Dryden, Byron, Scott, Hayden, and Churchill, which according to Adams “implicitly admit to a deep human pleasure to dominating others—a delight at the surface of Homer—and address the need to control that pleasure” (12), superhero comics began as an oxymoronic genre of sanitized hyperviolence, pleasing young readers by avoiding direct representations of its most central subject matter.

Tags: comic book violence

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

15/05/17 Super LGBTQ in the 80s

The 1980s are often recalled as the conservative Reagan years. But they were also a tipping point in the superheroic battle for gay rights. LGBTQ characters in comics began the decade as villains and ended it with a revised Comics Code that championed their “orientation.”

Although England’s Wolfenden Commission recommended decriminalizing homosexuality in 1957, and the American Law Institute made a similar recommendation in 1962, the 1971 Comics Code update remained unchanged from its 1950s version. “Sexual abnormalities” were still “unacceptable” and “the protection of the children and family life” paramount—even after the American Psychiatric Association struck homosexuality from its mental disorder list in 1973. As a result, superhero comics avoided gay characters until the 1980s, and early depictions cast them as villains.

Beginning in Peter Parker, The Spectacular Spider-Man #43, Roger Stern scripted Roderick Kingsley as a thin, limp-wristed, ascot-wearing fashion designer who another characters calls a “flaming simp!” and who is later revealed to be the supervillain Hobgoblin (1980).

Kingsley is not directly identified as gay, but the same year in the non-Code Hulk Magazine #23, Jim Shooter and Roger Stern scripted two men, one black and one white, attempting to rape Bruce Banner, who escapes a YMCA shower room by threatening to transform into the Hulk: “You hurt me and I’ll get big and green and tear your … head off!”

Alan Moore and John Totleben recreate a similar scene eight years later in Miracleman #14 when three teens succeed in raping the pubescent Johnny Bates: “You love it. You littul poof. Say you love it.” He escapes by actually transforming into the monstrous Kid Miracleman, who then massacres thousands of Londoners before being forced to transform back, leading Miracleman to murder Johnny to prevent future massacres—all the results of a homosexual rape.

Early depictions of transgender characters are comparatively positive. Because a character’s consciousness is often depicted as existing independently of the character’s body, superhero comics provide a range of opportunities for fantastical gender-switching. In 1975, writer Steve Gerber introduced Starhawk, a male superhero who exchanges bodies with his female lover, Aleta. Jim Shooter scripted Starhawk in The Avengers #168: “Aleta gestures in defiance as her persona submerges, giving way – as the persona of Starhawk assumes command, the corporeal form they share shimmers… changes.” Although both characters are heterosexual and cisgender, the visual depiction of a woman transforming into a male superhero alters the male-to-male norm established in Action Comics #1.

Mike W. Barra and Brian Bolland’s 1982 Camelot 3000 introduced a more overtly transgender superhero, the legendary knight Sir Tristan reincarnated into a woman’s body. Tristan rejects a female sex identity until the maxi-series’ conclusion when he chooses to live as a woman with his reincarnated female lover Isolde.

Beginning in the 1987 Alpha Flight #45, Bill Mantlo scripted a more convoluted, multiple body-swapping plot that concluded with the spirit of a previously deceased male character, Walter Langkowski, inside a formerly deceased female body—except when Langkowski transforms into the male body of the Hulk-like Sasquatch for superheroic adventures. Like Sir Tristan, Langkowski, taking the first name “Wanda,” continued a previous romantic relationship with his female lover.

While challenging gender binaries, these early depictions of transgender and gay superheroes also maintain aspects of traditional masculinity and heterosexuality. The female Aleta transforming into the male Starhawk literalizes the emasculated or female-like nature of Clark Kent already implicit in the formula. With Tristan and Langkowski, a female body is controlled by a male consciousness, and the male consciousness is male by virtue of having existed previously in a male body. The physicality of the male body, even when not currently present, is primary. Tristan and Langkowski also treat transgender as a temporary plot conflict resolved by a male consciousness accepting a female sex identity through what visually appears to be a lesbian romance, normalizing same-sex female relationships as fantastical expressions of heterosexuality. None of the narratives present a female consciousness inhabiting a male body or male bodies in sexual relationships. Since only female homosexuality is visually portrayed and because early depictions of gay men are villainous, superhero masculinity remained heterosexual and homophobic.

John Byrne challenged that norm in 1983 with Alpha Flight superhero Northstar. Because the Code barred openly gay characters, Byrne suggested the character’s sexuality indirectly, for example, introducing his friend Raymonde Belmonde whom Byrne draws in a nearly identical light blue suit and red ascot that Mike Zeck designed for Roderick Kingsley four years earlier. Byrne was either alluding to Zeck or both were drawing on the same cultural stereotype—arguably the blue suit worn by an emaciated David Bowie on the album cover of the 1974 David Live.

Despite more direct portrayals of same-sex superhero relationships in non-Code-approved issues of The Defenders and Vigilante in 1984, Bill Mantlo continued the pattern of indirection when scripting Alpha Flight in 1985. When he began a 1987 story arc in which Northstar contracts AIDS, Marvel under the editorship of Jim Shooter altered the disease to a fantastical ailment, forcing the character into temporary retirement. Other writers followed a similar approach, including gay characters while avoiding identifying their sexualities overtly. Scripter Al Milgrom in the 1988 Marvel Fanfare #40 moved closer to confirming the relationship between mutants Mystique and Destiny originally intended and implied by Chris Claremont in 1981.

Paul Levitz, during his 63-issue, 1984-89 run of DC’s Legion of Super-Heroes, also indirectly indicated that the 60s characters Lightning Lass and Shrinking Violet were lesbian lovers, a subplot continued by the next team of writers in 1989. Alan Moore’s 1986 Watchmen memoirist Hollis Mason alludes to two gay superheroes, Hooded Justice and the Silhouette, both of whom may have been murdered for their sexualities.

DC’s Steve Englehart and Joe Stanton’s 1988-9 The New Guardians featured the flamboyantly effeminate Extrano, who wore a large golden earring and a purple cape but was never explicitly identified as gay. John Byrne also introduced police captain Maggie Sawyer to Superman in 1987, interrupting Superman mid-sentence before he could explicitly identify her as lesbian.

The increase in gay representation parallels gains of the gay rights movement of the 80s. Wisconsin, for example, became the first state to outlaw discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in 1982, and 600,000 protesters marched in Washington in support of gay rights in 1987. “After decades existing in a subtextual closet of metaphors, tropes, and stereotypes,” writes Sean Guynes, “in 1988 openly gay characters exploded in the pages of superhero comics” (2016: 182). When the Comics Code Authority revised its guidelines in 1989, it reversed its quarter century of anti-gay mandates. The Code’s new “Characterizations” subsection required creators to “show sensitivity to national, ethnic, religious, sexual, political and socioeconomic orientations.” The revision also acknowledged that heroes “should reflect the prevailing social attitudes,” potentially allowing positive portrayals of openly gay superheroes.

As a result, LGBTQ characters transformed radically in the 90s. That happier history is here.

Tags: gay superheroes, lesbian, trans characters

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

08/05/17 Political Superhero Team-up: Super Goat Man and Passivityman!

I know, you never heard of either. But this dynamic duo reveals more about the politics of superheroes than do the contents of most comic shops. Jonathan Lethem’s short story “Super Goat Man” appeared in The New Yorker in April 2004, and Deborah Eisenberg (also a New Yorker fav) published “Twilight of the Superheroes” that fall.

Why were literary Avengers assembling in 2004? I’ll get back to that. First a recap:

I was born in 1966, Lethem a little earlier, his narrator Everett a little before that—not the start of the Silver Age, but the start of its relevancy. Everett’s birth also parallels the escalation of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Like me, Super Goat Man and his narrator became professors in “the harmless pantheon of academia.” Everett ends his tale on the job market. If I’m doing the math right, that’s 1993, same year my wife landed her current academic position. Everett is postdocing at Rutgers, where my wife and I met as undergrads. We married in 1993, same as Everett and his wife, a fellow medievalist.

Similarities end there, since, to the best of my knowledge, neither my wife nor I ever had sex with Super Goat Man.

Lethem offers no explanation for Super Goat Man’s fantastical leap (“fall from grace,” Everett calls it) from comic book pages to real world Brooklyn where Everett first indifferently meets him. He was “at best a minor star” in a small publisher’s five-issue run that Everett finds “embarrassing.” In the flesh he’s just a guy in a sleeveless undershirt who happened to have “two little fleshy horns on his forehead.” When he says, “I lost my job” for “being too outspoken about the war,” he means his superhero job, not his alter ego’s college position, which he quit after Kennedy was shot. How that relates to his “ludicrous and boring” adventures rescuing cats and old ladies in comics, Lethem doesn’t explain.

Everett and the other kids prefer “superheroes in two dimensions,” but their dads are entranced because Super Goat Man “represented some lost possibility in their own lives.” That possibility is never realized though. When next seen, Super Goat Man is goaded by college students to display his superpowers, but when he’s unable to catch a falling drunk with his prehensile toes, the kid ends up paralyzed.

“Had the hero,” asks Everett, “failed the crisis? Caused it, by innate provocation? Or was the bogus crisis unworthy, and the outcome its own reward? Who’d shamed whom?”

As a drawing Super Goat Man was “amateurish, cut-rate, antiquated,” but in his final appearance, he’s worse, “reduced to a kind of honorary position” as “a campus mascot.” He’s “quite infirm” due to his “accelerated aging process,” a result of the “sacrifice he’d made, enunciating his political views so long ago.” He has literally “shrunk,” not “five feet tall” now, and sometimes drops “to all fours” and shakes himself “like a wet dog,” unaware of his “sacrificed dignity.” He declares in his “sepulchral” voice: “All this controversy . . . not worth it,” meaning “his lost career.” But Everett’s “loathing” is directed at his own father’s “susceptibility to the notion of a hero.”

If all that doesn’t sound very superheroic, wait till you meet Deborah Eisenberg’s Passivityman.

I took a couple of MFA classes from Eisenberg just as her collection Twilight of the Superheroes was published in 2006. Because the title track had been rejected by The New Yorker and its ilk, Eisenberg’s boyfriend (that’s her term) Wallace Shaun created Final Edition, a literary one-off, to spotlight the short story rather than release it to shallower literary waters (where I do most of my own submission fishing).

Eisenberg’s superhero is the creation of Nathaniel, a twentysomething slacker facing his and his friends’ imminent expulsion from their ritzy, Manhattan sublet. When Nathaniel started Passivityman in junior high, he battled Captain Corporation in “a comic strip that ran in free papers all over parts of the Mid-west, a comic strip that was doted on by whole dozens . . . of stoned undergrads.” Nowadays, Nathaniel’s friends uncomfortably notice, the hero has become “intellectually passive,” even “passive-aggressive,” more like “his morally neutral, transgendering twin, Ambiguityperson.” Passivityman, like Nathaniel and his dispersing friends, is “losing his superpowers.”

Though the team’s “holding pattern” may have something to do with “the eternal, poignant weariness of youth,” the more immediate problem is 9/11. They were all out there on the terrace when the towers came down. Nathaniel keeps “waiting for that shattering day to unhappen, so that the real—the intended—future, the one that had been implied by the past, could unfold.” Meanwhile, his superhero’s rallying cry, “No way,” morphs into “Whatever,” until Nathaniel has “all but stopped trying to work on Passsivityman.”

When I interviewed Eisenberg for an article in U.Va’s alumni magazine, she credited Wallace (she actually calls him “Wall” and carries a Star Trek: Deep Space Nine trading card of him as the Grand Nagus of the Ferengi Alliance) with starting her writing career. He was also “incensed when the three highest-profile magazines rejected” her “Twilight of the Superheroes.” And thus was born Final Edition, a political magazine by writers “who seriously believe that part of our national problem is that the people who run the country have a crude and minimal imaginative life.”

In addition to Eisenberg’s short story, Shaun included Jonathan Schell’s essay “Invitation to a Degraded World.” Since 9/11, it seemed to Schell, “history was being authored by a third-rate writer rather than a master, or was being compelled, even as it visited increasing suffering on real people, to follow the plot of a bad comic book,” in part because of the tone-setting “appearance of Osama bin Laden, a mass murderer who came across at the same time as a comic-book, caricature villain.” Sadly, Bush accepted “Bin Laden’s invitation to enter into the world of an apocalyptic comic book,” dividing “every person and government on earth into two camps — the good, the lovers of freedom, who are ‘with us,’ and the ‘evil-doers’ who hate the good ones for their very goodness,” while turning “himself into a sort of real life action figure . . . on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln to declare success in the Iraq.” As a result, not only was “the quality of political discussion and decision-making” damaged but “the dignity of the real.”

And that gets us back to Super Goat Man. Everett knows two-dimensional heroes belong in a two-dimensional world. Lethem’s cut-rate hero enters our world via the fantastical conduit of 9/11 and its on-going sequel, The War of Terror, and as a result both he and America deteriorate. Superheroes follow a formula of goofy but absolute good vs. reassuringly simple evil. They can’t cope with the complexities of politics—either in protest of the Vietnam War or the implementation of counter-terrorism. Superheroes and the real world shame each other.

Passivityman can’t cope either. He needed the two-dimensional “curtain” that divided him from “the dark world that lay right behind it, of populations ruthlessly exploited, inflamed with hatred, and tired of waiting for change to happen by.” The curtain had been “painted with the map of the earth, its oceans and contents, with [his] delightful city.” And the 9/11 planes tore through it.

The opposite of a superhero isn’t a supervillain. When exposed to three-dimensional reality, superheroes transform into their true opposites: irredeemable failures.

The drift toward comic book simplicity continued after 2004–until the reality-leaping election of Donald Trump flattened the political landscape in a single bound. Now the failings of George Bush seem nostalgically complex. Trump drew himself as a two-dimensional fantasy for white male Republicans longing for an old-school hero. That’s why Everett’s “loathing” for Super Goat Man is really about his father’s “susceptibility to the notion of a hero” and the damage it does to “the dignity of the real.” A majority of Americans would like that “shattering day to unhappen,” but unlike Nathaniel, they haven’t morphed into Passivityman. They aren’t sitting around, waiting for “the real—the intended—future, the one that had been implied by the past” to return. They’re tearing open the curtain themselves.

Tags: Deborah Eisenberg, Invitation to a Degraded World, Jonathan Lethem, Jonathan Schell, Super Goat Man, The New Yorker, Twilight of the Superheroes, Wallace Shaun

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

01/05/17 Super LGBTQ

Last month I looked at LGBTQ characters in the early comics years. There were very few and most were negative. Starting in the 90s, that all changes.

Publishing in DC’s non-Code Vertigo imprint, Neil Gaiman’s Sandman introduced comics’ first overt and non-fantastical trans characters in 1991, another “Wanda,” who Shawn McManus renders with awkwardly masculine features. Within Code-approved comics, scripter William Messner-Loebs revealed the first openly gay character, the Pied Piper, in Flash #53 the same year. Flash asks whether the Joker is gay and the former 60s supervillain answers: “He’s a sadist and a psychopath … I doubt he has real feelings of any kind… He’s not gay, Wally. In fact, I can’t think of any super-villain who is … Well, except me of course” (Messner-Lobes & LaRocque 1991).

Marvel now allowed Scott Lobdell to script Northstar’s declaration in the 1992 Alpha Flight #106: “For while I am not inclined to discuss my sexuality with people for whom it is none of their business – I am gay!” (Lobdell & Pacella 1992). Mark Pacella’s cover features a close-up of Northstar’s shouting, eye-clenched face and the header: “NORTHSTAR AS YOU’VE NEVER KNOWN HIM BEFORE!” Pacella also renders him in the hyper-muscular style that was standard for male superheroes in the 90s. His costume, the same worn by all Alpha Flight members, is non-symmetrical and so metaphorically a rejection of simple binaries.

Four months later at DC, Legion of Super-Heroes writers Mary and Tom Bierbaum revealed that Element Lad’s long-time girlfriend had been born in a male body and was transforming it with the fantastical drug Profin. The two continue their previously heterosexual relationship now as male lovers: “it doesn’t matter,” says Element Lad, “You just have to understand – this is not what’s changed between us […] anything we shared physically … it was in spite of the Profin, not because of it!” (Bierbaum et al 1992). The relationship echoes Tristan and Isolde of a decade earlier, only now with a gender-fluid character accepting a male sex identity through the resolution of a same-sex male romance. Male homosexuality had entered superhero masculinity.

In 1993, the year President Clinton signed “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” into military policy, Milestone Comics’ Blood Syndicate #1 introduced scripters Dwayne McDuffie and Ivan Velez, Jr’s Masquerade, a black trans man who assumes a male form as a shapeshifter. The same year, DC’s Vertigo published two limited series featuring gay superheroes as title characters: Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell’s Sebastian O and Peter Milligan and Duncan Fegredo’s The Enigma, which included an image of a gay kiss and a full-page image of the naked lovers entwined in bed after sex: “two men redrawing the maps of themselves.”

In 1994, David Peter scripted the Pantheon superhero Hector as gay in Incredible Hulk. In 1997, Supergirl featured the shapeshifter Comet who alternates between a female human identity and a male centaur. In 1998 James Robinson’s Starman #48 featured the title character kissing his boyfriend. Alan Moore included a trans woman incarnation of the female superhero Promethea in 1999. In 2001, Peter Milligan and Mike Allred’s X-Force #118 included a kiss between two male superheroes, and the following year in The Authority #29 Mark Millar and Gary Erskine married superheroes Apollo and Midnighter, whom creator Warren Ellis had established as openly gay in 1999. Writer Judd Winick introduced the openly gay character Terry Berg to Green Lantern in 2001, and the 2002 #154-5 “Hate Crime” plot portrays his brutal beating and Green Lantern’s near deadly retaliation—reversing the 1980 and 1988 portrayals of gay men as violent predators.

21st-century comics continued the expansion of LGBTQ representation, including John Constantine in Hellblazer (2002), Moondragon and Marlo Chandler-Jones in Captain Marvel (2002), Renee Montoya in Gotham Central (2003), Xavin and Karolina in Runaways (2003), Miss Masque in Terra Obscura (2003), the rebooted Rawhide Kid in Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather (2003), Hulking and Wiccan in Young Avengers (2005), Freedom Ring in Marvel Team-Up (2006), Erik Storn as Amazing Woman in Infinity Inc. (2007), Daken in Wolverine Origins (2007), Loki in Thor (2008), Kate Kane and Maggie Sawyer in Batwoman (2011), Bunker in Teen Titans (2011), Miss America Chavez in Vengeance (2011), Northstar’s marriage in Astonishing X-Men (2012), Alan Scott Green Lantern in Earth Two (2012), Hercules and Wolverine in X-Treme X-Men (2013), and Alysia Yeoh in Batgirl (2013). 2015 alone includes Iceman in Uncanny X-Men, Sera and Angela in Angela: Asgard’s Assassin, Catman in Secret Six, Alpha Centurian in Doomed, Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy in Harley Quinn, Batwoman in DC Comics Bombshells, and Catwoman. Probably the most prominent challenge to the superhero’s traditional gender binaries is Deadpool, who in the opening pages of the 2016 Spider-Man/Deadpool #1 “Isn’t it Bromantic?” Joe Kelly and Ed McGuiness depict in an explicitly sexual conversation with Spider-Man as the two are tied together and about to be killed by a demon horde as they hang upside down.

DEADPOOL: I have to tell you one last thing that is, in my humble opinion, the single most important thing you need to know in the whole universe right at this second … If you don’t stop squirming, I am totally going to “unsheathe my katana” all up against your “spider eggs.” And by “katana” I mean –

SPIDER-MAN: What is wrong with you?

DEADPOOL: What?! I’m a red-blooded Canadian male! It’s friction and junk-biology and spandex grinding on leather and just please stop wiggling your webbing –

SPIDER-MAN: Would you just shut up so I can think!

DEADPOOL: Don’t yell at me … that’s totally one of my turn-ons. (2016: 1-3).

The 2015 film Deadpool also alluded to the character’s pansexuality—a stark contrast to the contractual agreement between Sony and Marvel requiring that Peter Parker be “Caucasian and heterosexual” (Biddle). Finally, new Wonder Woman writer Greg Rucka stated in an interview that Wonder Woman’s home island “is a queer culture” and that Wonder Woman “has been in love and had relationships with other women,” facts he hopes to “show” rather than “tell” in future episodes (Santori-Griffith 2016).

Visually and narratively, however, LGBTQ superheroes are often little different from heterosexual, cisgender superheroes. “Though demarcated by an explicit declaration of their same-sex object choice,” writes Panuska, “it is often difficult to otherwise cordon … ‘gay’ superheroes from their heterosexual counterparts” because they still conform “to the traditions of a nearly 80-year-old genre” and so do not “stray from traditional associations” (2013: 25). While female and LGBTQ superheroes have significantly challenged the traditional superhero formula, Michael A. Chaney in the Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender still concludes that the genre affirms “the fantasy of a masculine universe” in which “the objectifying conventions of superhero illustration disrupt the very forays into progressive gender politics (cyborg sexuality, transgender, nongender, etc.) that superhero stories increasingly undertake” (2007).

John G. Cawalti, writing in 1976 while black superheroes embodied racist stereotypes and LGBTQ superheroes were non-existent, analyzed the relationship between formula literature, such as superhero comics, and the culture that produces it, arguing that such “stories affirm existing interests and attitudes by presenting an imaginary world that is aligned with these interests and attitudes” and so “help to maintain a culture’s ongoing consensus” by “confirming some strongly held conventional view” (1976: 35). The comic book superhero—white, male, heterosexual, cisgender, and non-disabled—has served this function since its conception. But, as Cawalti also argues, popular fiction formulas also “assist in the process of assimilating changes in values to traditional imaginative constructs” and so “ease the transition between old and new ways of expressing things and thus contribute to cultural continuity” (36). The comic book superhero, a continuous cultural construct since 1938, demonstrates this capacity by evolving in response to larger social attitudes, reflecting progressive shifts within conservative norms. The history of black and LGBTQ superheroes demonstrates that superhero comics are rarely agents of cultural change, but that once a social attitude has shifted, comics quickly follow and so reinforce the new status quo.

Tags: deapool, element lad, gay, lgbtq, northstar, pied piper, sandman, Wanda, Wonder Woman

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized