Monthly Archives: December 2012

31/12/12 Return to Middle-earth

My family and I spent the first half of 2011 in Middle-earth. We took a bus tour to Rivendell and Hobbiton. We have a family photo of ourselves posed where Frodo and his friends tumbled down that hill before the Dark Riders almost caught them. Minas Tirith and Helm’s Deep are gone, but we parked across the street from the industrial park where they’d been built. It turned out Isengard was just a public park. The base of Saruman’s tower had been a blue screen draped in front of a children’s swing set. When Aragorn’s horse finds him washed ashore on a Rohan river bank, they had to angle out the power lines and row of suburban houses.

Still, Middle-earth (AKA Aotearoa, AKA New Zealand) is a magical place in my book. I spent most of my time there drafting the first half of a novel (the one that shares its name with this blog) and chauffeuring my wife and kids to their various schools. My wife’s sorcery (AKA Fulbright research grant) flung us to the other side of the planet. But the real magic was my 13-year-old daughter’s transformation after we landed.

Never underestimate the power of changing worlds. Flash Gordon, John Carter, Superman, they all became extraordinary by leaving their homes and adventuring in faraway lands.

That means leaving your old identity behind. My daughter had been haunted by a third grade assignment where everyone wrote descriptions of their classmates. She received the same word over and over: Quiet, Quiet, Quiet, Quiet. Actually, they all misspelled it, “Quite,” but the effect was the same. A spell that bound her.

Until she stepped off that plane in Wellington, NZ. When she walked into a sea of identically uniformed Wellington Girls College students, not one of them knew her. She could be anyone. The spell was broken.

It terrified her, no safety net of friends between her and the abyss, but after a couple of weeks, she cooked up a spell of her own: The Audacious American Girl. She crossed out the word “quiet” and wrote “loud.” She took to the part like a pro, a better method actor than Sir Ian or Viggo Mortensen. Nobody could contradict her. Her laughter drowned them out.

Meanwhile, New Zealand’s directorial superhero Peter Jackson was at it again. The Hobbit was in full production. We’d toured the outskirts of his Wellington studio, glimpsed the giant green wall where he conjured universes of possibilities. He flew into a benefit event at a newly refurbished theater dressed as retro-superhero The Rocketeer, before unmasking and posing with his Hobbit cast. It made the front page of the local paper, which I showed my kids over breakfasts of crumpets and muesli.

I ignored the casting call for extras, something I still half-regret. My wife loved me in that elf costume the tour bus driver made me pose in. But I had other spells to complete. I wanted to return to Virginia with most of a novel written.

And what would happen when my Supergirl had to rocket home? All those old friends and their loving shards of kryptonite, would they unmask her refurbished self and destroy the enchantment?

It turns out Middle-earth magic works in our realm too. My quiet thirteen-year-old daughter returned an audaciously loud fourteen-year-old.

Which had some downsides too. Her suddenly flourishing social life meant less family time. She would only watch the occasional Merlin or Sherlock with us now. Family movie outings were taboo.

Until The Hobbit. We didn’t even coerce her. A year and a half away from Middle-earth is long enough. We’d watched The Lord of the Rings trilogy on our Wellington couch. My wife read the series aloud to both kids about a decade ago. I’d claimed the Oz books, and they got Harry Potter from us both. I think they heard The Hobbit twice too. The family copy is on our son’s bedroom shelves right now.

With the exception of The Cat in the Hat, The Hobbit trilogy promises to be the fist book adaptation that takes longer to watch than to read. The first installment runs a little under three hours. Leaving just enough time for my daughter to make her dinner shift at our local pizza place after the matinee.

Much of it is worthwhile. Though the two musical numbers are a bit surreal, in a bad way. And the rock giant battle should win an Oscar for most gratuitous use of CGI. I prefer Martin Freeman as the BBC’s most recent Watson, but he makes a perfectly acceptable Bilbo too. (I didn’t spot him, but I hear Sherlock got one of those no-name elf roles I spurned). It was also a delight to see our favorite vampire from Being Human (explaining why he got staked at the end of season 3). But Gollum’s scene is by far far far the most entertaining fifteen minutes of the film. Which bodes badly for the next two, since he won’t be in them.

But all that New Zealand scenery will be. Shot after breathtaking shot of south island mountain terrain, it’s actually real. I drove it. On the wrong side of the road, white knuckled, with my wife flailing in the passenger seat, Orcs and Goblins gaining in the rear view mirror. It’s a magical place. Too bad we have to wait another year to go back again. The Hobbit 2 release date is December 2013.

Who knows what new spells my daughter will have learned by then.

Tags: Lord of the Rings, New Zealand, Peter Jackson, The Hobbit, The Rocketeer, Tolkien, Wellington

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

24/12/12 Shape-Shifting Super-President Wins 2012 Chameleon Award

The supervillain of Amazing Spider-Man #1 is a little-remembered master-of-disguise called the Chameleon. He later received an alter ego (Dmitri Smerdyakov) and backstory (abused brother/servant of Kraven the Hunter), but in 1963 he was just a guy with a face as featureless as an Oscar statue’s.

Which is why I’m asking the Academy Awards to name a new category after him: Best Shape-shifting Performance in a Motion Picture.

My nomination goes to Lincoln.

Much of the credit for mutating Daniel Day-Lewis into our 16th President belongs to the make-up team. I think Spielberg tricked a few of the camera angles too (something Kenneth Branagh did to lesser effect for Robert De Niro in the 1994 Frankenstein). And he probably set his casting director a maximum height requirement as well (when Spielberg shot War of the Worlds in my town, all our local extras had to stand below Tom Cruise’s mighty 5’ 7”).

But Hollywood gimmickry can’t match Day-Lewis’ own Chameleon-like superpowers. At 6′ 2,” he had to stretch himself another two inches to achieve his Lincoln-esque stature. Which might sound easy if you weren’t simultaneously stooping, creating the air of a freakishly tall man desperate to look shorter (because back then Tom Cruise would have been a titan). Add Lincoln’s implausibly high voice, something Day-Lewis imbues with both humility and gravitas, and you have an impersonation equal to the Chameleon’s framing of Spider-Man when he stole those defense plans after the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Day-Lewis isn’t the film’s only successful shapeshifter. But his is the only performance that erases the presence of the actor. For all her talent, Sally Fields in a period dress remains Sally Fields in a period dress. The rest of the equally admirable cast of character actors never quite escapes the Where’s Waldo effect. As in: “Hey look, isn’t that the guy who plays Professor X on Alphas?”

But it’s not Day-Lewis who should accept the film’s Chameleon award. It’s Spielberg and writer Tony Kushner. They’re the ones who shapeshifted 2012 into an improbably identical 1865. They’ve proven that the scifi truism, “the future is just like the present only more so,” applies to the past too. Or at least whichever historical snapshot a film-maker decides to dust off and frame anew.

It’s not hard to see why they tackled Lincoln in the age of Obama vs. the Tea Party. A President synonymous with racial change wins a legislative battle in a bitterly divided Congress through the power of compromise. Sound familiar? Spielberg even timed its release during the current lame duck session of Congress, same political timeframe as the film. If Obama had lost in November, or the legislative battle about the fiscal cliff been averted, Lincoln would lose many of its superpowers.

Instead, majority leader Harry Reid adjourned the Senate early last Wednesday for a 5:00 screening, followed by a Q&A with the director, writer and star. (Spielberg had already attended a screening with Obama at the White House.)

But it’s the House of Representatives who should be watching. Tommy Lee Jones reprises his role as Two-Face to give today’s Tea Party a civics lesson in principled compromise. Are you listening Speaker Boehner?

Political shapeshifting isn’t spineless, it’s noble.

“When you think about what we’ve gone through, ” says President Lincoln, “the country deserves us to be willing to compromise on behalf of the greater good.” No, wait. That was Obama last week, talking about the debt deal. (These time travel plots are so confusing.)

I assume it’s coincidental that Tommy Lee resembles Thad Stevens less than he does John Boehner. To be fair, it’s actually Boehner who is a more attractive version of Jones. As if Boehner had been cast in a real life adaptation of the film. But instead of ending slavery, Boehner has to save America from the Debtpocalypse.

Or is that Governor Norquist’s job? Like Thad, the author of the sacred “Taxpayer Protection Pledge” bit the ideological bullet and endorsed Boehner’s “Plan B,” what would have been a tax hike on millionaires to prevent one on everybody making over $400,000 (the amount, coincidentally, Congress sets for the President’s salary).

But the Tea Party still said no, as they will to any compromise. Lincoln is just too hard a history lesson for the GOP to study right now. They just watched their last flag-bearer, the human Etch-A-Sketch Mitt Romney, go down in ignoble flames after his failed attempt to shapeshift into a moderate a month before election day.

No Academy Award nominations for that performance.

Even worse for Republicans, the formerly soft-spined President Obama has learned to flex his re-election muscles. He’s even promising gun control next. It all makes for a thrilling legislative drama. A subgenre of the political biopic I only just discovered. If I’d known the plot of Lincoln wasn’t the President’s life but the passage of the 13th Amendment, I might have stayed home. I’m lucky I didn’t.

If Congress can pass a cliff-averting fiscal bill, the whole country should feel lucky too. Then we can all stay home and watch the Academy Awards together.

I predict Lincoln wins in a landslide.

Tags: Daniel Day-Lewis, David Strathairn, John Boehner, Lincoln, Obama, Spielberg, Thad Stevens, The Chameleon, Tommy Lee Jones, Tony Kushner

- 1 comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

17/12/12 Batman’s Debt to the KKK (Or the Origin of an Origin)

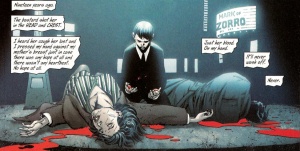

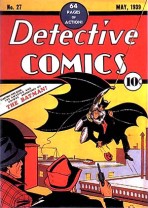

A little boy witnesses the murder of his parents and swears vengeance. It’s right up there with radioactive spiders and Krypton exploding. But Detective Comics ran six adventures before Bob Kane bothered to sketch in his hero’s background.

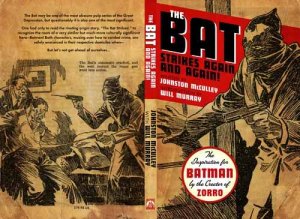

Legend has it that Kane was planning “Bird-Man” before his scripter Bill Finger steered him toward “Bat-Man.” After plagiarizing a Shadow novella for the first adventure, Finger (or possibly second string writer Gardner Fox) plagiarized an even more obscure pulp for the origin story. The 1934 “The Bat” is credited to C. K. M. Scanlon, a likely pseudonym for superhero trail-blazer Johnston McCulley (you know him for Zorro).

You also know how The Bat chose a crime-fighting identity:

“He would not be able to appear in public unless he was carefully and cleverly disguised. . . . he must become a figure of sinister import . . . A strange Nemesis that would eventually become a legendary terror to all of crimedon. . . In the shadows above his head came a slithering, flapping sort of sound. As the creature hovered above the lamp for an instant it cast a huge shadow upon the cabin wall. ‘That’s it!’ exclaimed Clade aloud. ‘I’ll call myself ‘The Bat.’

Five years later, Bruce Wayne also sits alone contemplating his own disguise:

“Criminals are a superstitious cowardly lot. So my disguise must be able to strike terror into their hearts. I must be a creature of the night, black, terrible . . . .”

Like McCulley’s Clade, Bruce’s needs are answered by a seemingly chance appearance, “As if in answer a huge bat flies in the open window!” Which provides Bruce his needed inspiration: “A bat! That’s it! It’s an omen. I shall become a BAT!” He stands in full costume in the concluding frame: “And thus is born the weird figure of the dark . . . this avenger of evil, ‘The Batman.’”

Comic book expert Will Murray was the first to identify Batman’s debt to The Bat, but the story goes deeper. Kane and McCulley were both influenced by an even older source. D. W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation (a disturbing combination of landmark film innovation and unbridled racism) contains the first origin story for a masked hero’s costume.

After seeing his homeland under “Negro rule,” future Klan leader Ben Cameron sits alone “In agony of soul over the degradation and ruin of his people.” A group of children appear as if in answer. Two white children place a white sheet over their heads, and the black children are terrified by the ghostly sight. “The inspiration.” Cameron stands, now ready to act. “The result. The Ku Klux Klan . . . .” In the next frame sit three mounted Clansmen in full costume.

The sequence prefigures not only Batman’s three-panel origin structure—hero alone, chance inspiration, first image of costumed persona—but also the “superstitious” rationalization for the disguise.

Promotional posters for the film also featured a Klansmen on horseback, his cape fluttering and his Klan emblem centered on his chest. After Action Comics No. 1, these would become standard motifs of the superhero costume. It seems unlikely that Joe Shuster, a young Jewish artist from Cleveland, knowingly copied his Superman from anti-Semitic vigilantes, but Birth of a Nation and the Klan of the 20’s and 30’s had blurred into popular culture by the time he took up his pens.

Bill Finger’s plagiaristic impulses, however, are better documented. Finger was only a year old when Birth of a Nation premiered in theaters, but a sound version was re-released in 1930, giving him and the rest of the Batman creative team opportunity to view it first hand. McCulley was already 32 in 1915. He would not have needed to view the film a second time to be influenced by the origin sequence. Most likely McCulley borrowed from Griffith, and Finger borrowed from McCulley.

But however you draw the lines of influence, the KKK still haunts one of comic book’s most cherished superheroes.

[If you’re interested in a fuller treatment of this argument, see “The Ku Klux Klan and the birth of the Superhero” in Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics.]

Tags: Ben Cameron, Bill Finger, Bob Kane, C. K. M. Scanlon, D. W. Griffith, Gardner Fox, Johnston McCulley, The Bat, The Birth of a Nation, Will Murray

- 5 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

10/12/12 The KKK and the Birth of the Superhero

I was maybe ten when someone threw a burning cross in a front yard down the street from our house. I didn’t know the family who lived there, just the fact that they were black. My dad doubted it was the Klan, just some local Neanderthals. Maybe the same ones who egged our house and wrote “Niger Lovers” on our garage years before. (Presumably real Klan members would spell the racial slur correctly).

I was too busy reading Marvel Comics to think much more about it, but I mention the event as a kind of apology for one of the more unpleasant discoveries I’ve made while following the superhero back to its origins.

When searching for superhero ground zero, many scholars point to Baroness Orczy’s 1905 Scarlet Pimpernel largely because of Johnston McCulley’s imitative Zorro in 1919, which in turn influenced the 1939 Batman (Bill Finger included stills from the Douglass Fairbanks film when he handed his scripts to Bob Kane to draw).

But the Scarlet Pimpernel lacks one of the superhero’s most defining characteristics. He has no costume, no repeating physical representation. He is only a name and a series of ordinary disguises. (He’s also remarkably non-violent, preferring to deter an enemy with a snuff box of pepper than a blow to the jaw.)

Another historical novel published in 1905 offers a more convincing (though disturbing) predecessor to the modern superhero. Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman is a fancifully offensive portrayal of the KKK as a heroic band of Southern patriots battling the corruption of Northern tyranny. They are also the first 20th century dual identity costumed heroes in American literature.

Like superheroes, Dixon’s clansmen keep their alter egos a secret and hide their costumes with them (“easily folded within a blanket and kept under the saddle in a crowd without discovery”). They change “in the woods,” the nineteenth-century equivalent of Clark Kent’s phone booth (“It required less than two minutes to remove the saddles, place the disguises, and remount”). Their powers, while a product of their numbers and organization, border on the supernatural (their “ghostlike shadowy columns” rode “through the ten townships of the country and successfully disarmed every negro before day without the loss of a life”).

Dixon’s novel was so popular it became the source material for D. W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation, which in turn proved so successful, it inspired the Klan to reform across the U.S. (Their defining emblem, the burning cross, was invented by Dixon. The Reconstruction-era Klan never used it.)

The new KKK numbered in the millions and was praised as a much needed crime-fitting force that succeeded were traditional law enforcement failed. Historian Richard K. Tucker sums it up well:

“Mainline Protestant ministers often praised the Klan from their pulpits. Reformers welcomed it to vice-ridden communities to ‘clean up’ things. Prohibitionists and the Anti-Saloon League supported it as a force against the Demon Rum. Most of all, millions saw it as a protection against the Pope of Rome, who, they believed, was threatening to ‘take over America.'”

Vice-ridden communities, plots against America, only one thing can save us–any of this sound familiar?

There is an upside though. By the early 30s, the Klan were losing public approval. Though masked heroes sold millions of pulp magazines during the Depression, real life vigilantes were prosecuted as criminals. As a result, Superman began his career as a paradoxical vigilante-fighting vigilante, breaking up a lynch mob in the opening pages of Superman No. 1 in 1939

Superman and the legion of imitations who followed him take some of their most defining characteristics from the Klan (costumes, masked identities, codenames, emblems), while reversing the Klan’s political aims. As a result the superhero is a contradiction. A violent, anti-democratic vigilante fighting for law and order.

Dixon’s literary vision lived on in two incarnations from my childhood. Those Neanderthals roaming the suburbs of Pittsburgh in the early 70s. And the comic books I read then and am only now beginning fully to understand.

[If you’re interested in a fuller treatment of this argument, see “The Ku Klux Klan and the birth of the Superhero” in Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. The article goes online for subscribers this week and will be available in print later this year.]

Tags: Batman, D. W. Griffth, Ku Klux Klan, Niger lovers, Scarlet Pimpernel, Superman No. 1, The Birth of a Nation, The Clansman, Thomas Dixon, Zorro

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

03/12/12 So Why Superheroes?

Beware questions that begin: “Don’t take this the wrong way but.”

Which is how a friend recently asked me: “Why superheroes?”It’s a reasonable question. When my wife and another good friend spurred me to start a blog, I’m pretty sure neither had this one in mind.

In my defense, superhero scholarship is a pretty cool corner of academia to set up camp. And I’m not alone in the opinion. Elizabeth Bowie and Deborah Hallock, Life and Feature co-editors of the LBJ/LASA Liberator, were recently writing about the cultural and historical importance of superheroes and comic books. They contacted me, and our interview below may answer my friends’ question too.

What got you interested in the field?

A few years back some students from my college’s honors program were searching campus for someone willing to create a course about superheroes. My wife was chair of the English department at the time, and she gave them directions to my office. It sounded fun, so I said yes. I knew I’d have to do some research, but was expecting the pool to be fairly shallow. I was wrong. The more I looked, the more I discovered, the more I realized superheroes were an evolving character type that revealed a wide range of information about the larger culture. I now see them as a primary lens for understanding the social and political shifts of the twentieth century.

Why do you think superheroes are experiencing a surge in popularity right now? What do you think that says about America?

Marvel Entertainment figured out how to capitalize on its film investments. It’s largely a corporation-fed and corporation-maintained phenomenon. Our entertainment industry banks on familiarity. But there’s also an argument to be made that superheroes embody our post-9/11 zeitgeist. The character type first surged in comic books because of fascism. Without Adolf Hitler, Superman would never have made it to the cover of Action Comics in 1938. Comic books in the 21st century have largely vanished as a mass market product, but superheroes are now primarily a big budget film genre. Did that leap and surge happen in part because of Bin Laden? I think he helped.

How do you think America’s ideals are reflected in superhero culture?

Traditionally superheroes reduce complex issues to simple, child-like dimensions. The good guys are all good, and the bad guys are all bad. That’s a highly distorted but deeply reassuring way to look at the world. And the solution is always the same: righteous violence. America loves righteous violence. We also prefer our heroes to stand apart from our government, as a kind of incorruptible moral force that polices everything. Which means we embrace the myth of the benevolent vigilante, and superheroes are the ultimate example.

How do you think certain issues (such as social issues or even foreign policy) show themselves in the plot arcs and reactions of the characters?

The traditional superhero is all-powerful and all-good, which is the way the U.S. likes to perceive itself in the international arena. Other nations are the needy citizens of Gotham. In foreign policy, we want and expect the rest of the world to follow our lead. The superhero may be the greatest embodiment of American exceptionalism. When the Cold War ebbed, the role of the U.S. shifted and superhero mythology began to explore a lot of grey area in what had been a previously black and white universe. But World War II and Cold War nostalgia continue to haunt the genre. America loves supervillains. They help us define ourselves.

Are comic companies using this to reflect their personal ideals or those of ‘the general public’?

Corporations aren’t people, so they don’t have personal ideals. Their board members and managers may have individual ideals, but they have only one shared goal: to make money for the shareholders. That means crafting a product they believe will appeal to the largest number of people. Those products that do sell influence the next wave of products, and soon the public becomes conditioned too, so the marketplace both responds to and shapes consumer desire. Although products end up propagating certain social and political values, it’s not propaganda in the traditional sense because those values are a byproduct not a goal. Manufacturers just want your money. Capitalism is amoral, not immoral. If a product embodying an entirely different set of values sold better, they’d switch to it. As result, we tend to get what we want. Or, more accurately, what corporations think we want.

How have superheroes and comics remained culturally and historically relevant? Why were they important in the past?

They were important in the late 30s and 40s because they answered the national anxiety that democracy could collapse under the tide of fascism. Those superheroes paradoxically defended democracy by anti-democratic means. They were fascist-fighting fascists. As soon as the real fascists began to lose the war, superheroes started to fade. They boomed again in the early 60s, but not simply as cold warriors employing the same totalitarian ethic. The Marvel pantheon captured a different kind of fear, not of the Soviet Union but of war itself, of nuclear Armageddon. Superheroes mutated into radioactive monsters who, despite their own personal damage, fight to preserve society.

How do you think comics have changed with more recent interpretations?

When the Cold War ended, superheroes lost their traditional meaning. No Evil Empire, no nuclear doomsday either. Suddenly they, as the lone superpower, were the threat. Comics in the 80s and 90s and into the 21st century explore plots where the traditional goody good guys, unintentionally or intentionally, are the problem. It’s become one of the genre’s most central themes, though it has yet to make it to the big screen.

How do you think superheroes affect youth in their ideals and goals for the future? Why are they important to children?

Children don’t read comic books anymore. And Hollywood only makes superhero movies because of the previous successes and familiarity of ready-made characters. The WW2 superhero boom, while child-driven, was also fueled by adult readers, many of them soldiers. The nation was a child woken from a nightmare needing to be comforted in the most simple and efficient terms. Contemporary superheroes are aggressively marketed to children—or rather, to their parents who have built-in nostalgia for the characters. But despite all that, some children develop their own interests, so the genre must speak to something deeper. My own daughter fell in love with Superman and Batman—two characters I had no interest in as a kid or as a parent—without my help. She saw an image of Superman, and her curiosity spiked and never dropped. I think it’s the costumes. There’s nothing else quite so gloriously absurd.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized