Monthly Archives: December 2020

28/12/20 Mister Invincible vs. My Annoyingly Pretentious Comics Theory Terminology

Two annoying terms I can’t seem to stop using when discussing comics: ‘discourse’ and ‘diegesis.’ They’re sort of the same as ‘form’ and ‘content,’ or ‘form’ and ‘story.’ Except sometimes comics seems to crash form and story together, obscuring the distinction. Other art forms (prose fiction, films, live theater) have discourses and diegeses too, but the effects in comics might be unique.

One of the presents I unwrapped Christmas morning was Pascal Jousselin’s Mister Invincible: Local Hero, a collection of French comics translated and published in English in 2017, but new to my radar this year (which is why I put it on my Santa list–though all actual credit goes to my spouse). It’s one of the most playfully brilliant interrogations of the comics form I’ve seen, literally illustrating the discourse/diegesis divide and its peculiar comics conundrums.

First, with massive apologies to Jousselin, here are six panels from one of his collection’s one-page comic strips, rearranged in my own cascading column:

Though obscured by my arrangement, you probably see the key connection between panels 2 and 5. Ignoring the also vast issues of framing and perspective, my arrangement attempts to isolate each panel and emphasize the linear relationships of their content. This is close to the story as experienced by the woman worried about her cat.

Here’s another rearrangement, one that could more easily appear on an actual comics page, with paired panels in three rows:

The trick is still between panels 2 and 5, which is a little easier to see now because this arrangement places the interior content of each panel in roughly the same position relative to each other: the six trees line-up in two columns, parallel to the middle gutter.

Of course the drawings are all of only one tree: the one in the story world. That’s where annoying terms become usefully non-annoying. Using their adjective forms: there’s one diegetic tree, but six discursive trees. I could still say there’s one story-world tree, but saying there’s six formal trees is less clear, plus the formal effects of the cascading arrangement and the three rows of paired panels are different.

But not as different as the two rows of three panels that Jousselin actually drew:

Only now is the key conceptual connection between panels 2 and 5 also a physical connection. The arrangement is the joke. Mister Invincible’s superpower is the comics form. He seemingly reaches out of the diegesis and into the discourse of the page.

Though that’s not quite accurate. Understood diegetically, he just has time-travel powers: he can reach his arms out of his current moment and into another moment, removing an object (the cat) from that other moment and bringing it into the current moment. That would be the woman’s understanding of what happened. Mister Invincible, however, knows that his diegetic time-travel powers are rooted in the panel arrangement of the page. That’s why my first two arrangements ruin the joke.

But it’s more than panel arrangement. If, for example, panel 5 were drawn from a more distant perspective, so that the discursive space between the top of the tree were longer than the discursive length of Mister Invincible’s arms as drawn in the other panels, then he could not reach down and retrieve the cat. So it’s not just the layout of the panels but also the interior arrangements of their drawn content, including framing and perspective effects.

That means Mister Invincible sees everything that the viewers sees. He is aware of the page. That’s a delight of metafiction, but it reveals something else about the comics form: the layout of panels is not a formal quality; it’s a diegetic quality. Layout is part of Mister Invincible’s story world (and also his superhero-defining chest emblem).

Characters in other artforms can have metafictional qualities too: a character played by an actor turns and addresses the audience, either directly from a stage or seemingly through a camera and screen. A character in a prose novel might metaphorically break that fourth wall too, revealing that she knows she’s an author’s construction living in a constructed story world. But if so, she’s probably not aware of the ink that comprises the words that comprise her and that world. She’s not aware when the typeset words reach the right margin requiring a reader to shift to the left column to continuing reading. She’s not aware of paragraphs or page breaks either. She’s aware that her diegesis is a diegesis, but she’s unaware of the discourse (the physical book) that creates the diegesis (in collaboration with a reader reading it).

That doesn’t describe Mister Invincible. He doesn’t seem to be aware of his creator, Jousselin, or of viewers viewing his actions. I don’t know if he knows he’s in a diegesis. But I do know that an aspect of his diegesis is the discursive arrangement of image content on each page. That creates an interesting puzzle: while content and form can be related in all kinds of interesting ways, form can’t BE content. Instead of breaking the discourse/diegesis divide, Mister Invincible reveals that no such divide exists when it comes to what is typically called “form” in comics.

That means layout is not part of the comics form. It’s a kind of diegesis. Usually that diegesis is distinct from the character-populated world of the story, but it’s still a kind of diegesis, meaning a set of representations. The frames around the panels are not frames: they’re drawings of frames. The spaces between panels are not empty; they are drawings of emptiness. The only formal (meaning physical) parameters of a comics page are the physical edges of the paper that the ink is printed on. Mister Invincible is powerless against them because they exist only in the viewer’s world. The arrangement of panels is drawn to look like it exists in the viewer’s world too (like a gallery wall of framed images would actually exist in a viewer’s world), but that effect is no more real than the tree or the cat or the woman or Mister Invincible.

What do you call layout then? I’ve been puzzling through this while drafting my next book, The Comics Form: The Art of Sequenced Images (I just signed a new contract with Bloomsbury this month). While layout is a ‘secondary diegesis,’ the phrase misses its most salient features and could mean something entirely different (a story world within the story world). I first tried ‘pseudo-discourse,’ which made one of my collaborators (co-author of Creating Comics) laugh out loud–and not in a good way. So I’m currently going with the slightly less pretentious-sounding ‘pseudo-form.’

Comics panels are often drawn as though they are card-like images placed on the surface of a page. Sometimes they appear to overlap, either partially at corners, or entirely with insets, including panels that are insets on a full-page image. The word “on” is key. That’s a diegetic illusion. It’s all just ink marks beside inks marks (or pixels beside pixels). Only an illusion of diegetic content can appear to be “on” something else, as though that something else would be visible if the “top” content were somehow removed. It’s an illusion of depth–or let’s say ‘pseudo-depth’ since it’s distinct from the effects of depth created within the framed images through traditional naturalistic drawing techniques (three-dimensional perspective, light-sourced shading, etc.)

And that’s Mister Invincible’s improbable superpower: a panoptic awareness of and ability to navigate non-linearly but contiguously through the secondarily diegetic pseudo-form of each comics page.

He’s also a character in a really cute children’s comic I got for Christmas. Thanks, Santa!

- 2 comments

- Posted under Uncategorized

21/12/20 Black Superheroes Matter

That isn’t the name of my first-year writing seminar, but I considered it when revising my syllabus for the upcoming winter term.

I’ve taught my “Superheroes” section of WRIT 100 for years now, making incremental syllabus changes but never an outright reboot. I invariably begin with the first year of Superman, beginning with Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s Action Comics No. 1 (1938). I originally followed that with the first year of Batman in Bill Finger and Bob Kane’s Detective Comics (1939), establishing the cornerstones of the comics genre. After that I’ve swapped around a range of other media.

For films, I’ve always liked M. Night’s Shyamalan’s 2000 Unbreakable (though absolutely not his recent sequel Glass). It paired well with Peter Berg’s 2008 Hancock, especially the contrasting roles of Will Smith’s hero and Samuel L. Jackson’s villain. But the homophobia (not just Hancock’s casual insults, but the use of sitcom-style music playing after Hancock apparently shoves a man’s head into another man’s asshole) was just too much. At my daughter’s much appreciated insistence, I replaced it with Patty Jenkin’s 2017 Wonder Woman. (And if you think the gender of the director is insignificant, compare how Justice League director Zach Snyder centers his camera through Gal Godot’s thighs.)

For prose works, I started with Austin Grossman’s 2007 Soon I Will Be Invincible (still one of my favorite novels), but soon swapped it for editors Owen King and John McNally’s 2008 collection Who Will Save Us Now? Brand-New Superheroes and Their Amazing (Short) Stories (assigning literally all of the female authors, to balance the all-male authors of the early comics).

For poetry, Gary Jackson’s 2009 collection Missing You, Metropolis (which won the Cave Canem Poetry Prize) is unbeatable. (And as a happy result of teaching him, I also just completed a chapter on Jackson for the essay collection Mixed-Race Superheroes forthcoming next year from Rutgers University Press.)

At the end of each semester, I would return to comics for a contemporary look at superheroes. G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona’s 2014 Ms. Marvel: No Normal was always on the top of my and later my students’ favorite lists. Greg Rucka and J. H. Williams’ 2010 Batwoman: Elegy got more mixed reviews the more times I taught it, happily because the presentation of the first lesbian hero to star in her own series grew more dated as students questioned why the writer was making such a big deal about the character’s sexuality.

I like to assign a range of secondary readings too. Editors Robin S. Rosenberg and Peter Coogan’s 2013 essay collection What is a Superhero? (from Oxford) and Matthew J. Smith and Randy Duncan’s 2011 Critical Approaches to Comics (from Routledge) are useful. The gender balance in comics scholarship is not great, so I tend to highlight female scholars. Claire Pitkethly’s “Straddling a Boundary” is one of my all-time favorite essays, and Jennifer K. Stuller’s “What is a Female Superhero?” and “Feminism: Second-wave Feminism in the Pages of Lois Lane” have been equally helpful. Kara Kvaran’s “Super Daddy Issues: Parental Figures, Masculinity, and Superhero Films” was key for Unbreakable and Hancock. And how could I not include the introductory essay “Representation Matters” from Carolyn Cocca’s 2016 Eisner Award-winning Superwomen: Gender, Power, and Representation?

This year I’m adding an excerpt from Rachelle Cruz’s textbook Experiencing Comics (even better, Cruz is also joining the editorial board of my university’s literary journal Shenandoah as guest comics editor this winter). I’m also adding Kenneth Ghee’s “Will the Real Black Superheroes Please Stand up?! A Critical and Analysis of the Mythological Cultural Significance of Black Superheroes” from Black Comics: Politics of Race and Representation. That’s from Bloomsbury, an increasingly impressive home for comics studies, since they also publish Carolyn Cocca and Neil Cohn. (Happily, my and Leigh Ann Beavers’ textbook Creating Comics will be out from Bloomsbury next month, and I just signed a contract with them for my next book, The Comics Form, for 2022.)

In the past, I’ve tended to change one primary text at a time. For the section that starts in January, I’m adding works by three new authors: Nnedi Okorafor’s 2019 comic Shuri: The Search for Black Panther and her 2015 novella Binti (which won both the Hugo and Nebula awards for best novella);

Eve L. Ewing’s 2019 comic Ironheart: Those With Courage and her 2017 poetry collection Electric Arches (Ewing, who has a Ph.D. from Harvard, also wrote the 2018 Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side, which I considered excerpting, but a syllabus only has so much room);

and Ta-Nehisi Coates 2017 comic Black Panther and the Crew: We Are the Streets. I am also adding an excerpt of G. Willow Wilson’s 2010 memoir The Butterfly Mosque.

Okorafor’s Binti is not a superhero text, but I’m looking forward to reading the science fiction story about a young Black woman from a futuristic Earth traveling across the galaxy to attend a university against Okorafor’s portrayal of Shuri, the sister of the original Black Panther. Ewing’s Electric Arches is not superhero text either, but it should also read well against her portrayal of Riri Williams, the young Black woman who assumed the renamed role of Iron Man in 2015. It will also be nice to give Gary Jackson some poetry company. Wilson’s The Butterfly Mosque describes her conversion to Islam, which should add an interesting angle of analysis to her portrayal of Ms. Marvel, AKA Kamala Kahn. (Unlike previous years, my students should enter class with plenty of exposure to the correct pronunciation of her first name.)

Ta-Nehisi Coates is best known for Between the World and Me, which won the 2015 National Book Award for Nonfiction. Marvel Comics responded by offering Coates a new Black Panther series, which premiered in 2016. Black Panther and the Crew is one of his short-lived but therefore stand-alone spin-offs, featuring a range of Marvel’s Black superhero characters. I suspect it will especially resonate in our current Black Lives Matter context. (Unfortunately, my college announced after I placed my book orders that our winter calendar will include three “class free” days TBA, requiring some scheduled syllabus content to be cancelled. Since Coates is flying solo, his comic is a potential sacrifice–though I really hope not.)

I’m also adding a collection of William Moulton Marston and Harry Peter’s early 1940s Wonder Woman comics to pair with Superman (though the creators are all still male). In total I’m keeping three primary texts (Superman, Ms. Marvel, Gary Jackson) and adding six. That’s the most I’ve shaken up my WRIT 100 since I switched the course topic to superheroes five years ago (it used to be called “I see Dead People” and featured a lot of Henry James and zombies). An alumnus wrote and distributed his opinion essay to the W&L community two years ago, advocating that, based solely on my title “Superheroes,” the course and I should be “eliminated” for “dumbing down” the curriculum at W&L. Since my revised syllabus adds a National Book Award winner, a Nebula and Hugo Awards winner, and a Harvard Ph.D, in addition to a pre-existing Cave Canem Poetry Prize winner, I hope I am safe from that criticism this year.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

14/12/20 New Comics from Shenandoah!

When Shenandoah relaunched under the editorial vision of Beth Staples in fall 2018, I was lucky to be on board as the journal’s first comics editor. That rebirth issue featured comics artists Mita Mahato and Tillie Walden, and the subsequent issues have included seven more comics by creators: Miriam Libicki, Alice Blank, Marguerite Dabaie, Holly Burdorff, Fabio Lastrucci, Gregg Williard, and Marlon Hacla, and Kristine Ong Muslim.

Issue Volume 70, Number 1 just went live this week, and I think Beth was being a little too kind to me, because it features almost twice as many comics titles as previous issues:

Also, unlike those first few issues that featured only works from artists I had personally solicited, these artists all found their way to our Submittable portal unprompted–which I take as evidence of Shenandoah‘s increasing reputation not just as a prestigious literary journal (it’s been that for decades), but now also as major home for literary comics. The term “literary comics” is a new one, but I’m glad to see Shenandoah helping to define it. I had organized an AWP panel on the topic, “Comics Editors & Literary Journals,” but the pandemic had other plans. Happily though, Shenandoah is expanding its comics reach with guest comics editor Rachelle Cruz curating the Spring issue (if you don’t know her textbook Experiencing Comics, you should check it out).

Also, unlike those first few issues that featured only works from artists I had personally solicited, these artists all found their way to our Submittable portal unprompted–which I take as evidence of Shenandoah‘s increasing reputation not just as a prestigious literary journal (it’s been that for decades), but now also as major home for literary comics. The term “literary comics” is a new one, but I’m glad to see Shenandoah helping to define it. I had organized an AWP panel on the topic, “Comics Editors & Literary Journals,” but the pandemic had other plans. Happily though, Shenandoah is expanding its comics reach with guest comics editor Rachelle Cruz curating the Spring issue (if you don’t know her textbook Experiencing Comics, you should check it out).

First though, let me give some teasers for the winter issue’s cast of artists, starting with Angus Woodward’s “The Art Table.” I’m especially impressed by how Angus pushes against comics conventions, while still providing the narrative pleasures of the form.

Amy Collier’s “Birds You’re Watching and the Complex Histories You’ve Made up About Their Personal Lives Due to Boredom” is an especially (yet subtly) timely sequence that indirectly (and comically) evokes the psychological effects of the pandemic lockdown.

Unfished Unfinished in an artful comics ars poetica, shifting from black and white line art to full watercolor as it literally turns the form sideways.

excerpts from “AM/FM/PM” turn the form on its head, experimenting with the wonderful weirdness of juxtaposition (and, because of the online formatting, even a hint of match-cut animation).

Anger Management with paradoxical pleasure that invigorates even the letters of the static words.

We also owe Jenny an additional and massive thank you for the original watercolor portraits she painted of readers (poets, fiction writers, memoirists) from the Zoom launch party last week:

They’re all in the new issue!

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

07/12/20 One Plus One Is Ten

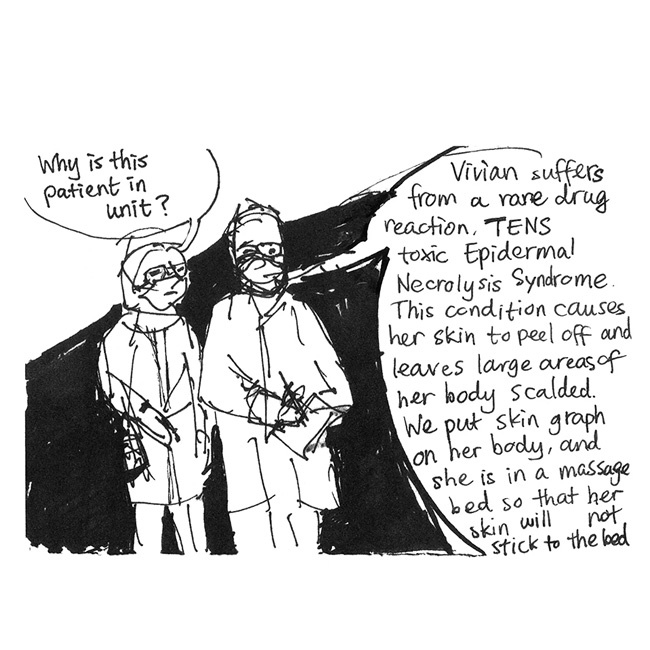

I’m always intrigued when I see two author names listed on a graphic memoir. I know what that usually means for a graphic novel: the first name belong to the writer, the second to the artist. But both Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber, the co-authors of the graphic memoir Dancing After TEN, are artists. For monthly comic books, that usually means the first name is the penciler’s, the second the inker’s. But again, not this time. Chong’s and Webber’s individual art sometimes occupies separate pages, sometimes separate panels on the same pages, and sometimes separate elements within shared panels. The combination is an interwoven visual conversation, based in part on actual face-to-face conversations they had at Chong’s kitchen table (as drawn by Webber). The memoir also merges—and in some cases literally tapes together—artwork spanning more than a dozen years.

Chong, who is now blind, briefly regained a portion of her vision and immediately began drawing a memoir of how she lost her sight to a rare syndrome (toxic epidermal necrolysis, or “TEN” of the title). Her regained sight only lasted a few weeks before the syndrome left her permanently blind, but she sketched dozens of images first, all in a frenetic sometimes scribbled style as her eyes worsened and she leaned her face closer and closer to the paper. She abandoned the project, but kept the pages and eventually shared them with Webber (via a theater director currently working on a play about Chong).

Webber once suffered a severe vocal injury, and Fantagraphics published her memoir, Dumb: Living Without a Voice, two years ago. She and Chong worked together, arranging and filling-in and further widening Chong’s initial artwork. The result is one of the most fascinating collaborations in the comics form I’ve ever seen.

I’m always interested in process and how a finished product encodes the history of its making, and that is nowhere more evident than in Dancing After TEN. Where the sudden shifts in style (Webber’s lines are thick, clean, and flowing—essentially the opposite of Chong’s thin, choppy ones) might feel disruptive in another work, they always gesture to not only the creative process (Chong and Webber seated together working) but the parallel disruptions in Chong’s actual experiences. The surface of Chong’s drawings tell the story of her losing her vision (her ex-boyfriend’s sister lied and gave a her pill that triggered the syndrome while they were on vacation), while their hectic execution evokes the much later story of her briefly regained vision.

The combinations are also artful in themselves. Webber’s lettering and speech containers appear within Chong’s drawings, and Chong’s drawings often provide backgrounds for Webber’s art. The two artists also chose a fitting two-color approach: each page combines a range of black and blue gradations, further unifying the memoir. Later pages also give space to each artist individually. Webber abandons the two-row panels that dominate the memoir for an open arrangement of more detailed figures and settings. The stylistic change parallels and so helps to express Chong’s psychological change as she embraces her new life. That includes taking up the pen again.

The final pages feature Chong’s new art, drawn with Webber’s encouragement. As Chong explains in an ending note: “TEN did not take away my ability draw, just my ability to see my drawings.” Some are abstract, a spray of lines evoking emotions. Others are representations of herself, sometimes with her seeing-eye-dog, sometimes her dancing alone. Her contour lines evoke shapes, movement, and, through their misalignments, the challenges of and her energetic responses to living without sight.

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/entertainment/books/2020/06/03/vivian-chong-was-creating-her-new-graphic-novel-then-she-went-blind-heres-what-happened-next/dancing_after_ten_freedom_is_my_forgiveness.jpg)

As much as I admire the combined artwork, I suspect most readers will be engaged by Chong’s story—not just the struggle and bravery of overcoming hardship, but her skill in shaping events and the extraordinary details of the plot. The opening chapters leap between distant moments: leaving from the airport for the eye surgery, arriving in St. Martin for the fateful vacation, deftly making tea for Webber in her apartment, waking from an induced coma. Wong weaves the fragments into emerging coherence that reverses the trajectory of her own trauma within the story.

She also depicts two of the biggest asshole boyfriends I’ve seen in a graphic memoir. Her portrayals are forgiving—literally when she declares her forgiveness to the one who abandoned her in the hospital and lied to their friends about where she was. The other one asks her to “watch” his bag at the terminal, complains that there’s no TV in her hospital room, leaves instead of taking notes for her while she’s consulting with doctors, hints that he doesn’t want to wait there if the surgery is gong to be long. I forget which one started sleeping with someone else while she lingered unconscious for two months. The grueling tale of her physical recovery parallels the psychological recovery from dating such shitty human beings.

The last third of the memoir loses some plot focus as a result. There are still fascinating details (Chong learns yoga, becomes a stand-up comic, overcomes her fear of dogs, loses her hearing), but the narrative shape is less satisfying—until the last portion draws in the memoir’s sweeping energy again. Dancing at TEN documents both an extraordinary life story and an extraordinary creative process that crowns it. Now I want tickets to Dancing with the Universe, a play that includes Chong dancing and performing as herself.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized