Tag Archives: Margo Lane

September 28, 2015 About Last Night

Superheroes just want to settle down and get married.

Or at least they used to. Spring-Heeled Jack, Night Wind, Gray Seal, Zorro, Blackshirt, most of the pre-Depression pulp crowd eventually hung up their masks and retired into the domestic oblivion of happily everafter.

Or tried to. Until their readers and publishers and writers demanded sequels. But once you’ve closed the marriage plot, it’s hard to pry it back open. Fortunately the early pulp writers invented a utility belt’s worth of solutions, all still in use:

1) Poker Night.

Yes, darling, we’re married now, but I still have my manly pastimes.

Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel kept it up for decades. Ditto for Graham Montague Jeffries’ Blackshirt. Just one problem though. No more titillating romantic subplot. The hero is domesticated, all that manly excess bunched neatly into his briefs. For Frederic van Rensselaer Dey’s Night Wind, that meant promising his new bride to stop breaking the arms of police officers who foolishly got in his way. By the second sequel, the speedster superman was barely using any of his mutant powers, and his series quietly petered away.

Domestication has proved equally disastrous for modern heroes. The mid-90’s Lois & Clark: the New Adventures of Superman enjoyed stellar ratings, right up to the wedding episode, after which viewership nosedived and the show was cancelled. Marriage is kryptonite. Even Orczy and Jeffries had to switch to other family members (sons and ancestors) to keep their plots going.

2) Dial M.

Wife holding you down? No problem. Just kill her.

Thanks so much, Louis Joseph Vance, for introducing this heartless trope in the first of your seven Lone Wolf sequels. Though his 1914 gentleman thief had happily settled down with the law enforcement agent who lovingly reformed him, Vance dispatches her between books, mentioning her death in passing chapter one dialogue. When Hollywood adapted Robert Ludlum’s first Bourne Identity sequel, they made sure we got to witness the girlfriend’s death (Ludlum, in chivalrous contrast, only sent her off to stay with relatives.)

It’s a grim choice, but one that acknowledges narrative logic. For the superhero to marry, he usually unmasks and retires, and so ending the retirement also ends the marriage. Happily everafter is also a hard place to scrape up plot conflict. In 1973, when Marvel could no longer write around Spider-Man’s eight years of romantic contentment, they shoved his girlfriend off a bridge. Gwen Stacy (and the Silver Age of comics) died with a SNAP! of her too happy neck. Gwen’s 2014 death had a similar effect on the Spider-Man film franchise.

3) Groundhog Day.

Marriage? What marriage?

Johnston McCulley is responsible for the first superhero reboot. When Douglass Fairbanks donned Zorro’s mask and turned an obscure vigilante hero into an international icon, McCulley simply ignored the ending of his own novel when he wrote his first sequel. Zorro did not unmask, he did not retire, and he certainly didn’t run off and get married.

This solution remains annoyingly common. After two decades of marital bliss between Peter Parker and Mary Jane, Marvel signed a deal with the devil (Mephisto in the comic) and rebooted an unmarried Spider-Man in 2008. Like Zorro, Peter had also unmasked publicly, an event erased from the minds of all onlookers (but not, alas, all readers). Lois and Clark, who were married (like their short-lived TV counterparts) in 1996, suffered the same fate when DC rebooted their entire, romantically-challenged universe in 2011. In fact, the very idea of the reboot came from the editorial staff’s frustration with the Lane-Kent status quo and how its innate dullness prevented them from cooking up a new Superman love triangle.

However you handle it, marriage is hell on a writer. But the last solution is my favorite:

4) Perpetual Foreplay.

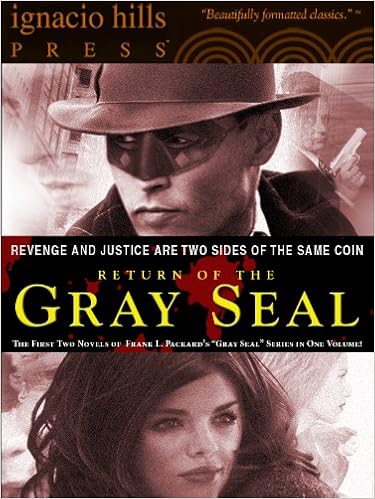

Frank Packard ended his first Gray Seal book with an implied bang. His proto-Batman waltzes off-stage with his superheroine girlfriend, unmasked nuptials to follow. But when bad guys and good sales returned the hero to active duty in 1919, the door to their bedroom bliss slammed shut. Since the Gray Seal’s do-gooding adventures were motivated not by revenge or altruism but superheroic lust for his bride-to-be, Packard needed to stretch out their romance plot. His four sequels offer increasingly frustrating reasons for why the lovers must remain divided.

Awkward as it sounds, Packard’s approach became the strategy of choice among 1930s pulp writers facing the titillating prospect of unlimited sequels.

Starting in 1933, The Spider magazine published a novella every month for a decade. Wealthy socialite Richard Wentworth fights crime as a costumed vigilante while also courting (and putting off) fiancé Nita Van Sloan. Norvell Page (writing under the house name Grant Stockbridge) tells us Wentworth must “sacrifice his hopes of personal happiness” because “the Spider could never marry,” could never “take on the responsibilities of wife and children” while continuing his crime-fighting mission.” Fortunately, Nita, like the Gray Seal’s would-be wife, is endlessly patient.

When William Gibson and Edward Hale Bierstadt adapted Gibson’s The Shadow for radio, they decided the lonely-hearted hero could use a fiancé too. The 1937 premier introduces Lamont Cranston and Margo Lane sipping coffee in his private library, as she begs him to end his career as the Shadow. He’d promised her as much five years ago when their courtship began, but Lamont, like Richard, feels “there is still so much to do” before he can settle down and unmask. “No, Margo,” he explains, “no one must know, no one but you.” And Margo, the ever dutiful (though ever jilted) help-mate, agrees.

But these women aren’t dupes either. They keep their own keys to the batcave. Nita is the Spider’s “best alley in the battle against crime,” “the one woman in the world who knew his secrets.” And Lamont calls the good accomplished by the Shadow “our activities.” Without Margo’s leg work, half of Gibson’s radio plots would stall.

But what other shared “activities” are these couple up to?

Page seems straight-forward enough: “Greatly they loved.” Nita and Richard (would you believe she calls him “Dick”?) share “pleasurable moments together,” though of course “all too brief.” How pleasurable? Page never penned a sex scene, but it’s clear Nina has access to Richard’s bedroom when she leaves him notes while he’s sleeping off a night of adventuring. As far as the Shadow, Alan Moore says it best in Watchmen: “I’d never been entirely sure what Lamont Cranston was up to with Margo Lane, but I’d bet it wasn’t near as innocent and wholesome as Clark Kent’s relationship with her namesake Lois.”

Since unmasking is the climax of the superhero romance plot, these lovers know each other in every sense. The marriage plots never technically closes, but pulp readers knew what was happening between the covers.

Tags: foreplay, jimmie dale, Lois and Clark, Margo Lane, mary jane, Spider-Man, superhero sex, The Shadow, The Spider, Zorro

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

August 15, 2011 Are Batman and Robin gay?

The short answer: Sort of.

Bob Kane never drew the dynamic duo in an intentionally compromising position, but were the two having sex in the gutters between the panels?

Can’t say. That’s the point of the comic book gutter. It requires the reader to fill in the narrative gap. If you read sex in that space, then sex it is. Frederic Wertham certainly did, and lots of it.

In his 1954 Seduction of the Innocent, Wertham famously explains: “Only someone ignorant of the fundamentals of psychiatry and of the psychopathology of sex can fail to realize a subtle atmosphere of homoerotism which pervades the adventures of the mature ‘Batman’ and his young friend ‘Robin.’ . . . They live in sumptuous quarters, with beautiful flowers in large vases, and have a butler, Alfred. Batman is sometimes shown in a dressing gown. . . . It is like a wish dream of two homosexuals living together. Sometimes they are shown on a couch, Bruce reclining and Dick sitting next to him, jacket off, collar open, and his hand on his friend’s arm. . . . [Robin] often stands with his legs spread, the genital region discreetly evident.”

Wertham is great fun to lampoon, but the question remains: What about Batman and Robin encourages someone, anyone, to read in sex?

The long answer:

Batman was a throwback to the mystery men of the 1930’s pulps. Bill Finger plagiarized the first “Bat-man” episode from a monthly Shadow novella published three years earlier. Though mystery men like the Shadow and the Spider never settled down and married, they did have partners, fiancées who knew exactly what was under their heroes’ costumes.

Alan Moore (through the fictional autobiography of a retired superhero in Watchmen) identifies “the repressed sex-urge” of the pulps (“I’d never been entirely sure what Lamont Cranston was up to with Margo Lane . . . .”), sensing that these heroes and their fiancées were not entirely “innocent and wholesome.” Writers like Walter Gibson and Norvell Page couldn’t depict sex, but they sure knew how to imply it.

For Batman’s fifth episode, Gardner Fox inserted a pulp-standard fiancée, Julie Madison, a character even Batman forgets after Robin debuts a few issues later. Comic book superheroes had a new breed of helpmate to share their secrets. Fiancées were out, and sidekicks were in. In addition to knowing all the ins and outs of Bruce’s Batcave, the Boy Wonder fulfills the same plot roles. “Like the girls in other stories,” observes Wertham, “Robin is sometimes held captive by the villains,” something Julie never got to do after her first appearance.

The narrative gaps in the Shadow’s and the Spider’s stories lured many readers’ minds to the gutter, a ploy to titillate without stepping into censorable sexuality. I doubt Bob Kane and his DC cohorts intended the same, but when they plumbed old stories for new material, they brought the pulps’ sexual baggage with it. As a result, Batman and Robin’s sexuality is hilariously ambiguous, but with no way to prove or disprove Wertham’s or anyone else’s claims.

The short answer: Batman and Robin are as gay as you want them to be.

Tags: Alan Moore, Batman and Robin, Bill Finger, Bob Kane, DC Comics, Frederic Wertham, Gardner Fox, Julie Madison, Lamont Cranston, Margo Lane, Norvell Page, Seduction of the Innocent, The Shadow, The Spider, Walter Gibson

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized