Tag Archives: Wonderman

September 5, 2016 The Superhero Monomyth?

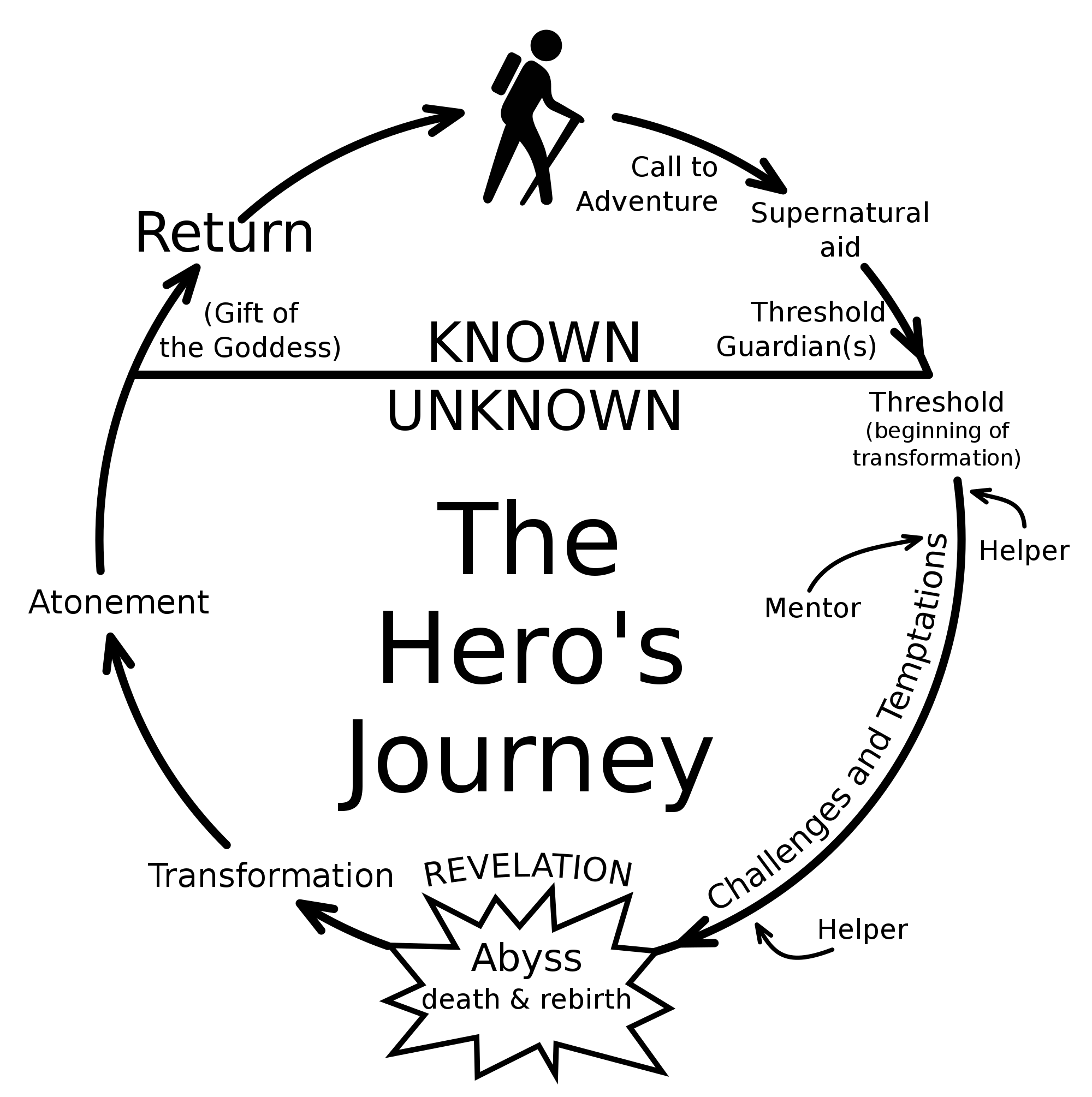

When Hollywood executive Christopher Vogler summarized Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces as a guide for screenwriters in 1985, he called it “one of the most influential books of the 20th century,” noting that “The myth can be used to tell the simplest comic book story or the most sophisticated drama.” Campbell’s book introduced his concept of the monomyth, an 18-step narrative formula he applied across societies and time periods world-wide. His examples include Greek, Roman, Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Norse, and Inuit sources. Campbell did not, however, relate his analysis to the hero type most popular while he was developing his formula in the 40s: the American comic book superhero.

Campbell published his study shortly after DC terminated Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, ending their ten-year contract on Action Comics. Superman, meanwhile, had expanded to newspapers, radio, film, and TV, producing a legion of similarly superhuman imitations. While Campbell’s approach to comparative mythology is flawed by inattention to differences between disparate tales and cultures, it shares its mid-century, American context with the superhero genre and so suggests one culturally-specific explanation for the character type’s popularity. What appealed to Campbell appealed to other 20th century U.S. readers too.

Campbell summarized his monomyth’s essential elements:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

The description encapsulates superhero origin stories. Will Eisner condensed the same elements into the first panel of Wonder Comics #1 (May 1939), when a blond-haired American vacationing in Asia receives supernatural powers from a turbaned Tibetan:

“So, Fred Carson, wear this ring as a symbol of the Herculean powers with which you are endowed—as long as you wear it, you will be the strongest human on Earth—you will be impervious—and now in the name of humanity and justice, go forth into the world!”

Wonderman premiered the same month as Action Comics #12 and Detective Comics #27, which introduced Bob Kane and Bill Finger’s “Bat-Man.” Both characters were the first direct imitations of Siegel and Shuster’s industry-transforming Superman. While Superman was influenced by decades of pulp, film, and penny dreadful predecessors, the medium-specific tradition of the comic book superhero begins in 1939 with the expansion of a single character into a repeated character type.

Like Wonderman’s, Batman’s origin story, retroactively inserted six months later in Detective Comics #33, is a monomyth variant—though a darker one. Bruce and his parents are “walking home from a movie” when they encounter the dark forces of the criminal underworld. After the “terror and shock” of the murders, a “curious and strange scene takes place,” in which Bruce vows to his parents’ spirits to avenge their deaths and so becomes “a creature of the night” himself. Finger places the formative event in an inexact past, “some twelve years ago,” suggesting the ahistoricity of many myths and folktales, while also grounding the ongoing consequences in a contemporary moment. The formula suggests comparative religion scholar Mircea Eliade’s analysis of a past mythic time and the ability of followers to return to it through ritual imitation. Superheroes pass between Campbell’s “two worlds, the divine and the human” regularly.

The relation of an origin to contemporary adventures is also central to the monomyth as embodied by superheroes. While Krypton is the original comic book region of supernatural wonder, giving Superman the power to bestow boons on humanity, Clark Kent is the ongoing embodiment of the world of the common day. Structurally the Krypton past is only preamble, establishing one of the most significant elements of Campbell’s heroic journey: personal transformation.

Myths and folktales are complete stories that end in closure, but superhero comics are typically episodic and endlessly incomplete. The monomyth as applied to comics form then is not limited to a character’s origin nor necessarily expandable to an accumulative series. The superhero monomyth is a single adventure—and, in fact, each and every adventure. The early twelve-page Action Comics episodes begin with Clark, who abandons his common day persona to encounter some fabulous force which he decisively defeats, before returning to live among humans as Clark again, his boon-bestowing powers at the ready.

If Campbell is correct, and the appeal of the myths he studied is grounded in the cyclic pattern of common heroes transforming through a descent into the fantastical, superhero comics enacted that script monthly. Every time Bill Parker and C.C. Beck’s little Billy Baston accepts a call to action and shouts “Shazam!” he receives the aid of his wizard mentor and crosses a supernatural threshold, causing Billy to vanishes and be reborn as Captain Marvel. Campbell writes:

“The hero, instead of conquering or conciliating the power of the threshold, is swallowed into the unknown and would appear to have died. … This popular motif gives emphasis to the lesson that the passage of the threshold is a form of self-annihilation … instead of passing outward, beyond the confines of the visible world, the hero goes inward, to be born again.”

After the trials of physical combat end in victory, Captain Marvel returns to the mundane world by transforming back into Billy Baston. Campbell describes the act as a trial itself:

“The first problem of the returning hero is to accept as real, after an experience of the soul-satisfying vision of fulfillment, the passing joys and sorrows, banalities and noisy obscenities of life. Why re-enter such a world? Why attempt to make plausible, or even interesting, to men and women consumed with passion, the experience of transcendental bliss? As dreams that were momentous by night may seem simply silly in the light of day, so the poet and the prophet can discover themselves playing the idiot before a jury of sober eyes.”

Siegel and Shuster solved Campbell’s dilemma by presenting Clark Kent as the hero’s banal disguise, allowing him to play an idiot to Lois Lane and the mundane temptations she represents. As Jules Feiffer concludes, Clark “is Superman’s opinion of the rest of us, a pointed caricature of what we … were really like.” Superman’s adoption of the caricature also reflects Campbell’s final monomythic stages, allowing him to remain in the never-ending moment by mastering both of his worlds:

“Freedom to pass back and forth across the world division, from the perspective of the apparitions of time to that of the causal deep and back—not contaminating the principles of the one with those of the other, yet permitting the mind to know the one by virtue of the other—is the talent of the master.”

Viewed within the monomythic scope of each episode, the Clark of the opening scene is fundamentally different from the Clark of the ending scene. If a reader had never heard of Superman, she would see a human transform into super-being and then relinquish that soul-satisfying fulfilment in order to appear human again. Other superheroes enact the same cyclic transformations every time they don a costume. Though Campbell’s monomyth can be applied only tentatively to the diverse array of world mythologies, it may find its most defining embodiment in the comics produced at its same cultural moment.

Tags: Batman, Captain Marvel, Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell, Monomyth, Superman, Wonderman

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized

January 27, 2014 Tibet, Superhero Tourist Destination of the World

Zarathustra came down from the mountain in 1883. He’s Nietzsche’s reboot of the ancient Iranian prophet Zoroaster—which means the first Superman came down from a mountain in Asia. It’s been a popular continent for superheroes since. When DC rival Fox Publishing needed a Superman knock-off, artist Will Eisener sent Wonderman to Tibet where a turbanded Tibetan was handing out magic rings.

Wonderman couldn’t survive the kryptonite of DC’s court injunction, so for Wonder Comics No. 2 Eisner swapped the colored tights and briefs for a tuxedo and amulet-crested turban. Yarko the Great was one of a dozen superhero magicians to materialize in comic books over the next three years. Nine of them shopped at the same turban store—though Zanzibar the Magician got confused and grabbed a Turkish fez instead. Three of them imported Asian servants too.

The tights-and-brief crowd rallied and sent a half dozen new supermen East, three specifically to Tibet, with Egypt as a solid runner-up. My favorite, Bill Everett’s Amazing Man, is almost as naked as his earlier Speedo-sporting Sub-Mariner, but Amazing Man has the power of the Tibetan Council of Seven on his side. He could also turn into “green mist,” which must have annoyed the hell out of the Green Lama. Jack Cole threw in a Fu-Manchu supervillain too: the Claw attacks America from “Tibet, land of strange religions and mysterious customs.”

When Stan Lee’s boss gave him the same assignment (do what DC is doing), he bee-lined back to Tibet for his and Jack Kirby’s first (and mostly forgotten) attempt at a superhero, the 1961 Doctor Droom. Kirby even gives the formerly Caucasian physician slanted eyes and a Fu Manchu moustache as his lama explains: “I have transformed you! I have given you an appearance suitable to your new role!”

Droom flopped, so Kirby sketched an iron mask and Lee dropped the “r” and, voila!, the supervillainous Doctor Doom was born. The following year Doom was “prowling the wastelands of Tibet, still seeking forbidden secrets of black magic and sorcery!”Another year and Doctor Strange returns from Tibet as “Master of Black Magic!” Strange also picked up Wong, one of those handy manservants Tibetans hand out with their superpowers. The third Doctor emptied Lee’s Tibetan well, but Roy Thomas and Gil Kane’s Iron Fist kept Orientalism thriving at Marvel into the 70s.

Over at Charlton Comics, Peter Morisi’s Thunderbolt returned from his Tibetan adventures with the standard superhero package. Since Alan Moore’s Watchmen were borrowed from Charlton characters, twenty years later his Ozymandias not only “traveled on, through China and Tibet, gathering martial wisdom” but was “transformed” by “a ball of hashish I was given in Tibet” and next things he’s “Adopting Ramses the Second’s Greek name.” Even the 21st century Batman, as retooled in Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, hops over to the Himalayas to learn his chops from yet another monkish mentor. And you’ll never guess where director Josh Trank sends his teen superhuman for the closing shot of the 2012 Chronicle.

The 1930s mystery men loved the Orient too. Before Walter Gibson’s Shadow emigrated from pulp pages to radio waves, he first “went to India, to Egypt, to China . . . to learn the old mysteries that modern science has not yet rediscovered, the natural magic.” When Harry Earnshaw and Raymond Morgan conjured Chandu the Magician for film serials, they sent their secret agent to India to study from another batch of compliant yogis. And not only did Lee Falk’s comic strip do-gooder Mandrake the Magician pick up his powers in Tibet, his Phantom found his dual identity in the India knock-off nation of “Bengalla” (which magically wanders to Africa in later stories).

Before Doctors Strange, Doom and Droom (not a practice included in Obamacare) earned their degrees in Tibet, Doctors Silence, Van Helsing and Hesselius interned their first. You can add Siegel and Shuster’s pre-Superman vampire-hunting Doctor Occult to the list of eligible providers too. Like those turban-obsessed magicians, these world-touring physicians are armed with Oriental knowhow. Algernon Blackwood’s Silence was a 1908 mummy-battling best-seller, cribbed from Bram Stoker’s 1897 Dracula. Stoker’s Van Helsing is an expert on “Eastern Europe” and labels his vampire nemesis “a man-eater, as they of India call the tiger who has once tasted blood of the human.” Joseph Sheridan LeFanu’s 1872 Dr. Hesselius hunts vamps too, but his first patient is an English reverend driven to suicide by visions of “a small black monkey” caused by his addiction to the “poison” green tea imported from China, ever the land of strange religions and mysterious customs.

Since none of the doctors bother to mention their mentors, the ur-guru award goes to Rudyard Kipling’s 1901 Kim. While no superhero, Kim is the prototypical colonial adventurer, and Kipling supplies him with his very own “guru from Tibet,” one who conveniently needs an English boy (for some reason Asian kids won’t do) to achieve his life-long spiritual quest. Kim in turn treats the guru “precisely as he would have investigated a new building or a strange festival in Lahore city. The lama was his trove, and he purposed to take possession.” Which soon became official policy for all aspiring superheroes trawling the Orient for superpowers. Kim and his guru even prefigure Batman and Robin—only reversed, since Asian mentors are just like underage sidekicks.

Despite Kim’s Superman-like influence on the genre, even Kipling has his predecessors. The first superhero to pinch his powers from an obliging Oriental is Spring-Heeled Jack. The masked Victorian used to leap through a dozen plays, penny dreadfuls, and dime novels. I like the Alfred Coates 1886 version. Jack’s dad reaps his fortunes in colonial India, and Jack returns to England with the workings of a “magical boot” that “savoured strongly of sorcery.” Jack “had for a tutor an old Moonshee, who had formerly been connected with a troop of conjurers—and you must have heard how clever the Indian conjurers are. . . Well, this Moonshee taught me the mechanism of a boot which . . . enabled him to spring fifteen or twenty feet in the air.” That old Moonshee (Jack must mean “munshi,” an Urdu word for writer that the Brits decided meant all clerks) is the first incarnation of Wonderman’s turbaned Tibetan.

The endlessly exotic Orient, the planet-spanning ring of Britain’s 19th century frontier. A superhero is the ultimate colonialist, seizing his fortunes in faraway lands and shipping them home to maintain his nation’s status quo, its global supremacy. It used to be the British Empire, then the American, but superheroes are always the imperial guard.

While Eisner’s imaginary Tibetan was handing out magical treasure in 1938, real Tibetans were arguing national autonomy with China and rights of succession with warring regents. Unlike Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, the actual Zoroaster did not declare, “God is dead.”He was all about exercising free will in the service of divine order and so becoming one with the Creator. I’ve not read any of his surviving texts, and I seriously doubt Nietzsche did either. I’ve also never set foot in Asia—though I did gaze at it from a cruise ship docked in Istanbul once, and that’s a lot closer than most comic book readers ever get.

[For more on this topic, my related essay, “The Imperial Superhero,” appears in the new PS: Political Science & Politics, as part of an eight-article symposium on the politics of the superhero.]

Tags: Nietzsche, Orientalsim, Will Eisner, Wonderman, Zoroaster

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Uncategorized